Cantigas de Santa Maria / Alla Francesca

Songs to the Virgin | Alfonso X “el Sabio”

medieval.org

Opus 111 30-308

2000

1. Nenbressete Madre de Deus [1:56]

CSM 421

chant TUTTI

2. Maravillosos e piadosos [3:05]

CSM 139

grande cornemuse PH · tambour à cordes FJ · grand tambourin BL

3. Quen a omagen da Virgen [5:12]

CSM 353

chant soliste BL · chœur BLB KL

paire de flûtes «satara» PH · vièle et archet à grelots EB · tambourin BL

4. U alguen a Jhesucristo [5:09]

CSM 281

chant EB PB

harpe BL · rebec EB · flûte traversière PH · flûte à six trous FJ ·

grande flûte à trois trous BLB · psaltérions KL CS

5. Como Jesucristo fezo a san Pedro [4:31]

CSM 369

chant soliste BL BLB · chœur TUTTI

flûte double PH · flûte

médiévale cylindrique FJ · cistre EB ·

tambourin à cymbalettes BL

6. Nunca ja pod' aa Virgen [2:41]

CSM 104

flûte médiévale cylindrique FJ · vièle EB · harpe BL · grand tambourin PH

7. O ffondo do mar [5:23]

CSM 383

chant EB PB · vièle EB

8. Nas mentes sempre teer [1:43]

CSM 29

cornemuses PH FJ · coquilles Saint-Jacques BL · castagnettes EB

9. Quen bona dona querra loar [2:59]

CSM 160

chant TUTTI · vièle EB

10. Non pod' ome pela Virgen [1:53]

CSM 127

paire de flûtes «satara» PH · flûte «Rafi» FJ · psaltérion EB

11. Pois que dos reis nostro Sennor [5:02]

CSM 424

chant soliste EB PB · chœur TUTTI · cornemuse à anche simple PH

12. Como o nome da Virgen [2:13]

CSM 194

flûtes «Rafi» PH FJ · grand tambourin BL

13. Gran piadad' e merce [5:43]

CSM 105

chant soliste BL · chœur TUTTI · récit KL · flûte traversière en bambou PH · vièle EB

14. Quen diz mal da Reynna espirital [4:19]

CSM 72

chant soliste EB · chœur TUTTI

harpe BL · vièle EB · petite flûte à 3 trous et tambour PH ·

petite flûte a 3 trous BLB · flûte médiévale cylindrique FJ · psaltérions KL CS

15. Santa Maria amar [5:43]

CSM 7

chant BL CS FJ · BLB KL · vièle EB

16. Pero que seja a gente [2:36]

CSM 181

cornemuse PH · flûte médiévale cylindrique

FJ · rebec EB · tambourin à cymbalettes BL

17. Null ome per ren [4:21]

CSM 361

chant PB CS · RB BLB KL

grandes flûtes à trois trous PH FJ BLB · petite flûte à 3 trous et tambour PH ·

cornemuse FJ · rebec EB · harpe BL · psaltérion KL

ALLA FRANCESCA

Brigitte Lesne BL chant · harpe · percussions

Emmanuel Bonnardot EB chant · vièle · rebec · cistre · psaltérion

Pierre Hamon PH flûtes à bec

· flûtes traversières · flûte double

· flûtes à trois trous et tambour ·

cornemuses

&

Pierre Bourhis PB chant

Florence Jacquemart FJ flûtes à bec · flûte à trois trous · cornemuse · chant

Brigitte Le Baron BLB chant · flûtes à trois trous

Katarina Livljanic KL chant · psaltérion

Catherine Sergent CS chant · psaltérion

Depuis sa création en 1989, l'ensemble ALLA FRANCESCA ressuscite

le répertoire oublié des chants et danses du Moyen Age.

S'imprégnant des techniques ancestrales survivant encore

aujourd'hui dans les musiques traditionnelles, et se confrontant sans

cesse à une pratique pédagogique enrichissant leur

recherche d'interprétation, cet ensemble nous entraîne sur

les chemins des troubadours, dans les cours divertissantes des

Seigneurs, dans les chambres des Dames... Chacun de leurs disques,

chacun de leurs nombreux concerts en France et partout dans le monde,

est un événement salué par la presse

entière, une fenêtre sur nos racines.

Desde su creación en 1989, el conjunto ALLA FRANCESCA resucita

el repertorio olvidado de los cantos y danzas de la Edad Media. Este

conjunto se impregna de las técnicas ancestrales que sobreviven

en nuestros días en las músicas tradicionales. La

practica pedagógica y la investigación técnica son

partes esenciales de su actividad. ALLA. FRANCESCA nos lleva por los

caminos de los trovadores, hacia las divertidas cortes de los

Señores, las cámaras de las Damas...Cada uno de sus

discos, cada uno de sus numerosos conciertos, en Francia y en el mundo

entero, un acontecimiento saludado por la prensa, una ventana abierta

hacia nuestras raíces.

The ensemble ALLA FRANCESCA, created in 1989, specialises in the

revival of the forgotten repertoire of songs and dances of the Middle

Ages. Their approach is based on immersion in the ancestral techniques

of traditional music. Teaching, research and studies of technique also

play a very important part, enabling the ensemble to take us along the

paths travelled by the Troubadours, attend entertainments at the courts

of the nobility, and eavesdrop in ladies' chambers... Each of their

recordings, each of their many concerts, in France and all over the

world, is an event unanimously hailed by the press, an open window on

the post and our roots.

Facture instrumentale

vièle et rebec, Judith Kraft

cistre, Bernard Prunier

psaltérions, Rudolf Hopfner et Bernard Prunier

flûtes médiévales cylindriques, Bob Marvin

flûtes à trois trous, Jeff Barbe

flûte double, Bob Marvin

flûte traversière, Philippe Allain-Dupré

flûte à six trous, Jonathan Swayne

flûte «Rafi», Adrian Brown, d'après un instrument signé Rafi

cornemuses, Rémy Dubois

harpe, Yves d'Arcizas d'après Jerome Bosch

grand tambourin, Norbert Eckermann

Instruments traditionnels:

flûte traversière en bambou, Europe centrale

paire de flûtes «satara», Rajasthan

cornemuse à anche simple | Tambourin à cymbalette Egypte

grand tambourin, Inde

Recording: Église luthérienne Saint Jean de Grenelle, Paris October 1999

Design: Heddie Bennour

Executive producer: Yolanta Skura

Recording producer & engineer: Laurence Heym

Editing: Laurence Heym

Studio Playback with Ensemble Loudspeakers

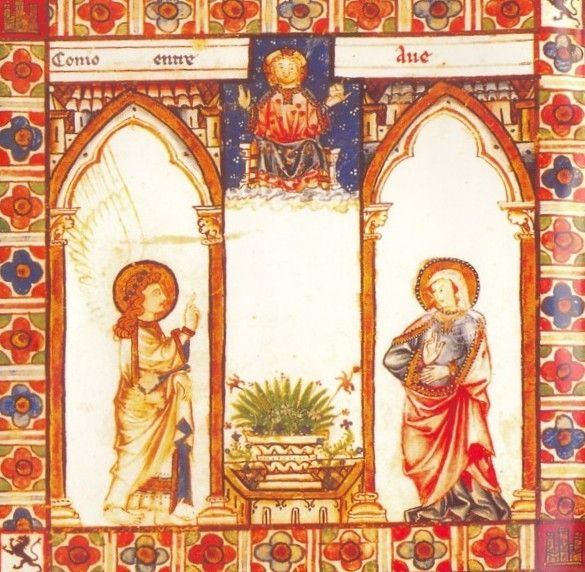

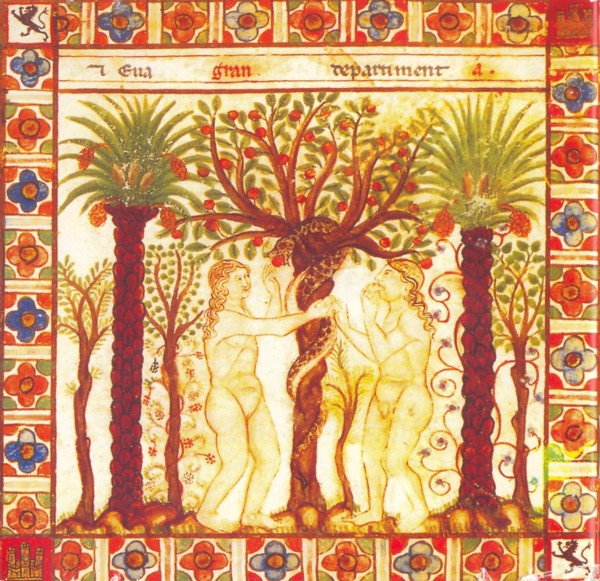

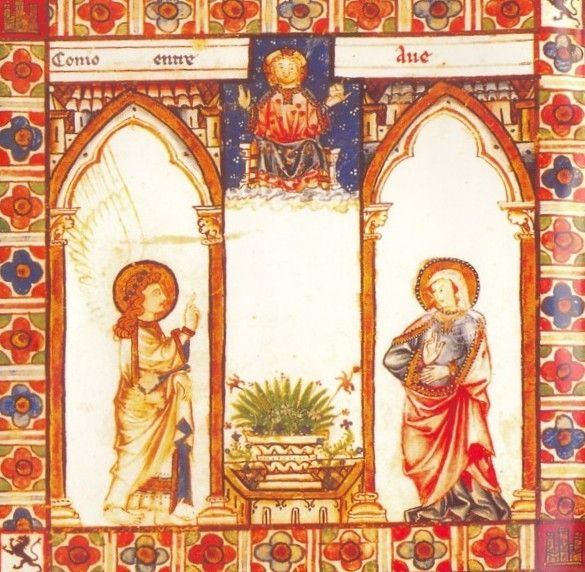

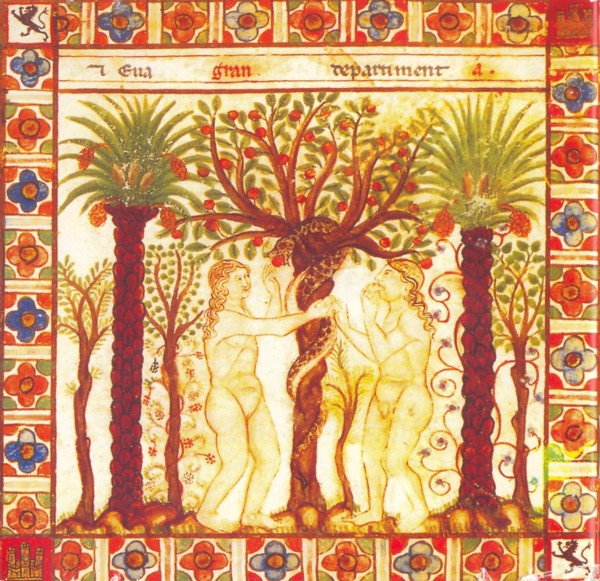

Cover: PRAISE X, song of praise for Saint Marie of Alphonse X "the wise". End of the XIII century.

Page 7: Pontifical Nicolas Gobert, Folio 26 front page, Funny detall: Lion playing rebec, Verdun, Public Library.

℗ & © 2000 OPUS 111

English liner notes

La teología, a partir de Bernardo de Clairvaux, confiere una gran

importancia a lo femenino, representado en la figura de María. Su papel

se entiende no sólo como el de la madre biológica del Dios encarnado,

sino como representación de una vida de compromiso libremente asumido:

con su fiat, María aceptaba poner su vida y su voluntad al

servicio de causas superiores. Por eso, en la actualidad existe un

crecimiento notable del interés por nuevos tipos de devociones marianas,

sobre todo entre los cristianos más comprometidos con la realidad

social. Con ello se está compensando el olvido que la modernidad, con

sus principios racionales y logocéntricos, había arrojado sobre lo

femenino en general, y, como consecuencia, sobre la mujer en particular.

María permanece así como encarnación de la generosidad, el altruismo y

el amor comprometido en la defensa de los débiles y los necesitados.

En la Edad Media hubo momentos en que esa imagen de María alcanzó una

gran difusión, quizás compensando así otros aspectos de la religión

demasiado ligados a las nociones de fuerza y poder terribles. El siglo

XIII fué uno de ellos: en todos los lugares donde había una cultura

escrita suficientemente desarrollada, se vieron aparecer recopilaciones

de historias y poemas de alabanza que ensalzaban las benefactoras

acciones de la Madre de Dios, al mismo tiempo que la producdón artística

presentaba imágenes marianas cada vez más numerosas para personificar

esos principios.

Las Cantigas de Alfonso X el Sabio

responden exactamente a ese movimiento cultural. Se trata de una

colección de más de 400 poemas, en los que se ensalza la generosidad de

María y se presentan exempla de sus intervenciones en la ayuda de

personas en dificultades. recomendando en consecuencia su devoción.

Aunque existen muchas obras de carácter mariano desde el siglo XI -

himnos, conductus y prosas, principalmente - estas están escritas en

latín y se dirigen a un público más restringido, pues utilizan un

discurso lleno de complicados conceptos teológicos y de expresiones

difíciles. Las Cantigas, en cambio, estar en lengua vulgar, y su

lenguaje es llano y sencillo, presentando sus temas de una forma muy

asequible para todos.

El rey Alfonso fue el primero que

introdujo el castellano en sus documentos oficiales, y también utilizó

esta lengua en sus producciones literarias en prosa. Pero para estos

poemas marianos escogió el galaico-portugués, probablemente porque el

castellano no tenía todavía una tradición suficiente como lengua

poétilca, y porque sus recursos, en consecuencìa, no eran suflcientes

para una empresa de la gran envergadura de esta. Aún así, la crícica

literaria encuentra sorprendente (y difícil) el uso del

galaico-portugués para un repertorio que es fundamentalmente narrativo,

ya que la tradición escrita de esta lengua era amorosa. Esto hace pensar

que en la voluntad del rey sabio contó no sólo el deseo de vulgarizar

la teología mariana sino también el de sublimar la figura de María como

epítome de la mujer cantada por la lírica cortesana: una mujer de

extremada nobleza y cualidades superlativas, situada más allá del

alcance humano. Su frase en el prólogo de las Cantigas confirma esta segunda impresión, cuando dice: quero seer oy mais seu trobaodor (quiero ser su trovador).

Estas dos líneas de pensamiento confluyen así en un enorme repertorio -

en su tipo, el más grande conocido - del que en este disco podremos

conocer una parte. Las Cantigas de loor o de alabanza a la Virgen (como Quen bona dona)

presentan los aspectos más líricos del tema, mientras que las

narrativas (el resto) ofrecen una serie de casos o ejemplos concretos de

María romo benefactora ideal. Así, podremos escuchar cómo ayuda, por

ejemplo, a una buena tendera acosada por una autoridad excesivamente

celosa de sus prerrogativas, a un juglar despojado por unos ladrones, a

una joven casada con un marido al que no ama, a una mujer caída al mar

por accidente, a un jugador perdido en tabernas y trampas, o a un

caballero arruinado. Contando estas historias como, si fueran ejemplos

de la vida real, la colección nos presenta de una forma fácil y

entretenida las tesis mariológicas de su tiempo, y, adicionalmente, nos

ofrece también un cuadro vivo de su sociedad.

A pesar de la

riqueza de los códices en que se copiaron estos poemas, y de la aparente

claridad de la notación musical, la interpretación práctica de la

música con que debían cantarse resulta más difícil de resolver,

especialmente por la falta de fuertes de información suficientes. La

vida del rey Alfonso es bien conocida en sus aspectos públicos, como sus

intervenciones bélicas para dejar la presencia musulmana en España

reducida a la tierra de Granada, y sus aspiraciones al trono imperial

por su vinculación familiar con a casa de Suabia; también se conocen sus

obras literarias, nacidas de la colaboración de un nutrido grupo de

intelectuales «de las tres culturas» (cristianos, judías, y musulmanes),

y destinadas a unificar en un corpus de conocimientos comunes un

país dividido en múltiples unidades históricas y sociales. Pero su vida

privada, y el papel que la música pudo jugar en ella, nos son

desconocidas.

Alfonso tenía su capilla religiosa propia, y sus ministriles,

pero las Cantigas no parecen destinadas ni a uno ni a otro de estos grupos musicales

a su servicio. Por otro lado, no existen documentos de su cancillería

que pudieran informarnos de los músicos que interpretaran eventualmente

este repertorio. Los códices que lo contienen fueron decorados con

numerosas miniaturas, relativas en unos casos a las historias relatadas

en los poemas, y en otros, a diversos músicos con sus instrumentos. De

ello podría deducirse el acompañamiento instrumental de las voces,

aunque la verdad es que esas preciosas miniaturas de músicos más parecen

destinadas a cumplir un papel alegórico y a ofrecer una «enumeración

gráfica» de los instrumentos, que a su interpretación real.

Otros problemas que plantea este repertorio a los intérpretes actuales

son la lectura exacta de la notación musical - el ritmo, en particular -

y las variantes existentes entre los diversos manuscritos que lo

conservan. El análisis estilístico de los textos demuestra que se trata

de una obra colectiva, puesto que la calidad literaria es muy variada;

en cuanto a la música, la variedad de materiales que se puede vislumbrar

permite aventurar la misma impresión. Efectivamente, estas piezas

recogen materiales melódicos procedentes de la tradición litúrgica tanto

como de la cortesana, y tanto ya conocidos como originales, que

presuponen que se adoptaron criterios musicales de procedencias

múltiples.

En su General Estoria - una crónica universal que realizó hacia 1270, poco antes de la parte principal de los trabajos para las Cantigas - el propio rey nos informa de cómo entendía él mismo su autoría: el

rey faze un libro, non porque l'él escriua con sus manos, mas porque

compone las razones dél, e las emiendas et yegua e enderesça, e muestra

la manera de cómo se deuen fazer, e desí escríuelas qui él manda (el

rey hace un libro no porque él lo escriba con sus manos, sino porque

decide sus fundamentos y lo corrige, y muestra a quien se lo encomienda

cómo se tiene que escribir). La existencia de variantes tendría que ver,

probablemente, con esta forma indi recta de organizar la composición

del conjunto de piezas, y esta composición continúa hoy en la persona de

los intérpretes, que deben completar las lecturas de su notación,

seleccionar sus variantes, y decidir sus sonoridades.

Con sus Cantigas

por tanto, el rey sabio dejó una obra viva que continúa estimulando la

creatividad de los músicos de hoy y que, al mismo tiempo, continúa

hablando al hombre actual a través del simbolismo de su temática.

CARMEN RODRÍGUEZ SUSO

Theology, from Bernard of Clairvaux onwards, conferred great importance

on things feminine, as represented by the figure of the Virgin Mary. The

latter was seen not only as the biological mother of God incarnate, but

also as the epitome of a freely assumed life of commitment with her fiat,

Mary agreed to devote her life and will to higher causes. This explains

the considerable growth of interest in new types of Marian worship in

the present day, particularly amongst those Christians who are most

closely involved with the realities of modern society — an interest

which makes up for the oblivion to which modernity, with its rational,

logocentric principles, had condemned things feminine in general, and

woman in particular. To this day, the Virgin Mary is thus regarded as

the embodiment of generosity, altruism, and a loving commitment to the

cause of the weak and the needy.

In the Middle Ages, there were

periods when this conception of the Virgin was very widespread, thus

possibly making up for other aspects of religion that were too closely

connected with dreadful ideas of strength and power. The thirteenth

century was one of those periods: wherever written culture was

sufficiently advanced, compilations of stories and poems appeared in

praise of the Mother of God and her beneficial influence. At the same

time, those principles were expressed in art through an ever-increasing

number of representations of the Virgin Mary.

The Cantigas

of Alfonso X el Sabio (the Learned, the Wise) are perfectly in keeping

with that cultural context. The collection comprises over four hundred

poems praising the generosity of the Virgin Mary, giving examples of her

intervention to assist persons in difficulty, and thereby advocating

the Marian cult. Many works had been dedicated to the Virgin Mary since

the eleventh century especially hymns, conductus and prose

pieces, which were written in Latin and were aimed at the narrow

audience that was capable of understanding complex theological concepts

and abstruse expressions. The Cantigas de Santa María, on the

other hand, were written in the vernacular using simple, straightforward

language: they were intended to be readily understandable to all.

King

Alfonso was the first to advocate the use of Castilian for official

documents, and he also employed the language for his literary prose

works. For his poems to the Virgin Mary, however, he used

Galiciarv-Portuguese, probably because Castilian did not have a

sufficiently well-established poetic tradition and was therefore not

strong enough for a large-scale undertaking such as the Cantigas.

The choice of Galician-Portuguese may nevertheless seem surprising (and

difficult) for a repertoire that is essentially narrative: it was

generally used for writings on the subject of love. This leads us to

believe that the desire to vulgarise Marian theology was not the

author's only concern: he also wished to sublimate the figure of Mary as

the epitome of femininity, as in courtly lyrical poetry. Mary is thus

portrayed as a woman of the highest nobility, possessing all the finest

qualities and situated well beyond the scope of human beings. Alfonso's

words in the prologue to the Cantigas bear this out. 'Quero seer oy mais seu trobador' he says — 'I want to be her troubadour'.

These

two lines of thought thus converge in this vast repertoire — the

largest known collection of its type — several pieces from which are

presented on this recording. The cantigas de loor or songs in praise of the Virgin Mary (Quen bona dona)

present the most lyrical aspects of the subject, while the narrative

songs (the other pieces) present a series of 'cases' or concrete

examples of Mary as the ideal benefactress. Thus we hear the tales of a

knight who, having lost all his fortune, forms a pact with the devil; a

good woman who is the victim of a plot motivated by jealousy; another

who is saved from drowning in the sea; a young woman who is forced to

marry against her will; an abbess who finds herself with child... In

relating these stories as if they were examples from everyday life, the

collection presents — in an easy and entertaining form — not only the

Marian doctrine of the time, but also a very lively picture of

contemporary society.

Despite the richness of the codices into

which these poems were copied, and the apparent clarity of the musical

notation, practical interpretation of the music accompanying the singing

poses many problems, because of insufficient sources of information.

The public aspects of King Alfonso's life are well known (his battles to

keep the Muslims out of Spain and confine them to Granada, his

aspirations to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire), and we also know

his literary works, which were produced in collaboration with a vast

group of intellectuals 'from the three cultures' (Christian, Jewish and

Muslim), thus aiming to unify a land that was divided into many

historical and social units by providing a common corpus of knowledge.

On the other hand, we know nothing about his private life and the part

played in it by music.

Alfonso had his own chapel and his own

minstrels, but apparently the Cantigas were intended for neither of

those bodies of musicians. Furthermore, his chancellery provides no

documents giving information on the musicians who might have performed

this repertoire. The manuscripts containing the Cantigas were

decorated with numerous miniatures, some of them illustrating the

stories related in the poems, others showing various musicians with

their instruments. We might therefore assume that the latter indicate

the instrumental accompaniment of the voices, but these precious

miniatures seem in fact to have a more allegorical role, presenting so

to speak a 'graphical enumeration' of the instruments, rather than

really telling us anything about interpretation.

This repertoire

also poses other problems for modern interpreters, it is difficult to

give an exact reading of the musical notation, particularly where rhythm

is concerned; furthermore, there are discrepancies between the various

manuscripts in which the songs appear. A stylistic analysis of the texts

reveals that the Cantigas are a collective work (their literary

quality is very uneven), and we may also hazard the same deduction (and

for the same reason) where the music is concerned. Indeed, many of these

pieces borrow melodic material from both the liturgical and the courtly

tradition, while others are known to be original. This leads us to

suppose that musical criteria from many different origins were adopted.

In his General Estoria — a world history, written in about 1270, shortly before the main body of his work on the Cantigas

— the king informs the reader of his conception of his role as a

writer, 'The king makes a book, not in that he writes it with his own

hands, but in that he determines its foundations and the corrections to

be made to it, and in that he shows those he commissions to write it how

they should go about it and how it should be written.' This no doubt

explains the existence of different versions, which also means that the

pieces continue to evolve to this day. For interpreters have to complete

the fragmental notation, select the variant they wish to perform, and

decide on the sound that is appropriate to each piece.

Alfonso el Sabio's Cantigas de Santa María

are still very much alive today. The wise and learned king left the

world a work that continues to stimulate the imagination and the

creativity of our musicians, and its symbolism still has much relevance

in the modern age.

CARMEN RODRÍGUEZ SUSO

Translation: Mary Pardoe