Iberian Garden, vol. 1 / Altramar

Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Music in Medieval Spain

“This is a very professional and well-done CD”

medieval.org

amazon.com

altramar.org

Dorian Discovery DIS-80 151

℗1995 ©1997

1. Lababi ya‛ireni kašo’el lašaharah [0:38]

reshut · Levi Ibn al-TABBAN (fl. late 11th century)

David

2. Dum pater familias [6:05]

cc 117

cantio · Codex Calixtinus

Angela, Allison, David, Chris, Jann (vihuela d'arco)

3. Raše ‛am ‛et hitassef [14:25]

muwashshah · Yehuda ha-LEVI (1075-1141)

Angela (solo, moroccan tabla), Jann (vihuela d'arco), Chris (darabukka), David (tar)

4.Rosa das rosas [10:31]

CSM 10

Cantigas de Santa María (13th century)

David (solo), Angela (voice, harp), Chris (lute), Jann (vihuela d'arco)

5. Ma li-l-muwallah [14:14]

muwashshah · Ibn ZUHR (1113-1198)

Angela (solo, lira), Chris (oud), Jann (rebec), David (darabukka)

6. Dona si totz temps vivia [7:59]

canso · Berenguer de PALOL (fl. early 12th century)

Allison (voice, harp)

7. Eno sagrado en Vigo [4:30]

ca VI

cantiga de amigo · Martin CODAX (fl. c.1230)

David (solo, duff), Angela (harp), Chris (vihuela da mano), Jann (vihuela d'arco)

Altramar

medieval music ensemble

Jann Cosart — vihuelas d'arco, rebecs

Angela Mariani — voice, harp, lira, percussion

Chris Smith — vihuela da mano, mozarabic lute, oud, percussion

David Stattelman — voice, percussion

with

Timothy G. Johnson — shawm

Allison Zelles, voice — harp, percussion

Altramar performs on a matched set of instruments especially designed

for them by luthier Timothy G. Johnson.

Oud — unknown Persian maker.

Altramar, in the Occitan language of the troubadours, was the

name given to the Near Eastern lands that lay "over the sea", where

crusade and trade resulted in the rich cultural interchange of East and

West.

Altramar is an ensemble specializing in music of the

Medieval Era, sharing historical repertory in the context of human

experience, and evoking the vibrant tapestry of medieval culture.

Altramar combines a process of collaborative partnership with a

commitment to scholarship and expression. Since 1991, Altramar has been

presenting their unique blend of song and story, drama and rhetoric, and

voices and instruments to audiences throughout North America.

Altramar

uses instruments appropriate to the times and places of their

repertoire. Most of the information about medieval instruments comes

from iconography, because very few of the originals survive. By studying

paintings and sculptures, one can discover which instruments were

played when and where. Also, clues can be found which suggest

construction techniques of medieval craftsmen. Luthier Timothy G.

Johnson has created a matched set of instruments for Altramar using this

type of research.

Altramar can be found on the World Wide Web at: http://www.indiana.edu/~altramar and contacted via eMail at: altramar@indiana.edu

Catalog No. DIS-80151

Recorded at The Church of the Immaculate Conception, Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, Indiana in December 1994 and November 1995.

Session Producers: Timothy G. Johnson, Peter Nothnagle

Engineer & Editor. Peter Nothnagle

Post Session Production: Altramar

Mastering Engineer: David H. Walters

Booklet Preparation & Editing: Katherine A. Dory

Graphic Design: Kimberly Smith Co.

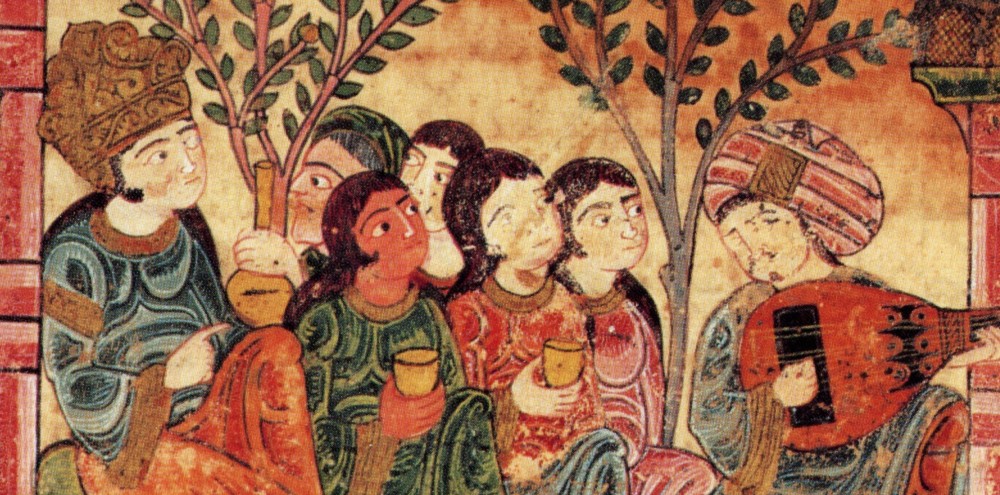

Cover Art: Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS. Vat. Arab, 368, fol. 10r.

Altramar

would like to thank Abdullah al-Malik, Luis Beltrán, Thomas Binkley,

Federico Corriente, Liljana Elverskog, Stephen Katz, Consuelo

Lopez-Morillas, James Monroe, Angel Saenz-Badillos, Josep Miguel Sobrer,

Byron Stayskal and the community of the Sisters of Providence, Saint

Mary-of-the-Woods, Indiana.

All transcriptions, reconstructions,

realizations, original compositions and arrangements copyright 1994 by

Altramar medieval music ensemble are protected under copyright law and

may not be used by others without express permission.

℗1995 Altramar

©1997 DORIAN DISCOVERY. A division of The Dorian Group, Ltd.

notas en español

In

the Middle Ages, the interaction of cultures in the Iberian Peninsula

created a cosmopolitan world in which people of differing ethnicities,

backgrounds and religious faiths lived, loved, battled, and learned from

one another. This was the Golden Age of Hebrew poetry, a high point of

Islamic science and art, a flowering of Christian theology and music;

all learned and shared in this Golden Age. Musicians and

mathematicians; poets, painters and politicians; architects and artists;

nobility and common people traded, studied, sang and worked together.

In 1993, the eminent scholar and performer Thomas Binkley challenged the members of Altramar

to create a program of medieval music that would, for the first time,

give equal representation to the extraordinary musical, literary and

spiritual diversity of Jewish, Christian and Muslim Spain. Such a

project, we all agreed, would require the inclusion of pieces in

Castilian, Catalan, Gallego-Portuguese, Latin, Hebrew, colloquial and

formal Arabic — and, in addition, a plethora of specific musical styles

and techniques. “If you can do that”, he said, “you really will have

done something unique”. Tom Binkley did not live to hear the final

result, but his indomitable spirit inspired and continues to inspire us.

The

attainment of our goal was a complex process. Primary sources for

poetic texts abound for all three cultures, and the existence of rich

and extensive musical activity is well-documented. But there is a

crucial gap in the evidence: while the Christian music traditions of

medieval Spain are preserved in manuscripts, and the post-medieval sung

repertoires of both Andalusian and Sephardic oral tradition are still

widely-performed, definitive sources for certifiably “medieval” Arabic

and Jewish melodies are scant or nonexistent.

Consequently, we

made a decision to use only texts known to originate in the medieval

period, and turned to firsthand medieval descriptions and to the

still-thriving oral traditions to inform our musical decisions. It is

our hope that the results, which are in one sense “new”, nevertheless

capture the sound and spirit of the old, displaying these jewels of

medieval sung-poetry in settings that aptly reflect their transcendent

beauty.

MUWASHSHAH AND ZAJAL

Some of the repertoire represented in this collection is in relatively familiar forms: hymn, cantiga, love lyric; even the piyyut

continues as a familiar part of the modern Jewish repertory. However,

some other forms, especially those from the Arabo-Andalusian tradition,

are perhaps less familiar.

The muwashshah and the zajal

developed as poetic and musical idioms in Arabic Spain during the tenth

and eleventh centuries, were subsequently borrowed by Hebrew poets, and

are still performed today in the Maghrib. Andalusian Jewish poets, many

of whom held high positions in culturally sophisticated Arabic courts,

admired and imitated the Arabic love lyric, whose lush and evocative

language they saw mirrored in the Song of Songs. Jewish poets of the

Golden Age synthesized elements of the Arabic repertoire's imagery and

conventions with their own rich poetic traditions, and the result was a

tradition that paralleled the Arabo-Andalusian one: muwashshahat in Hebrew on a variety of sacred and secular topics.

The text of the medieval Arabic muwashshah is typically in the classical language, while the second part of the last stanza, or jarcha,

is in either colloquial Arabic or a Hispanic romance dialect, and is

believed to be borrowed from popular sources. In another example of

parallel usage, the jarcha of the Hebrew muwashshah was

also often written in a Romance dialect, and thus displays an

interesting example of the interaction between vernacular and high-art

genres.

As part of the modern nawba, a suite of musical pieces grouped by mode and performed in sequence, the Arabo-Andalusian muwashshah is played by a group of instrumentalists and sung by either a chorus or a soloist alternating with choral refrains.1

The zajal,

the largest extant collection of which is by the Andalusian poet Ibn

Quzman, is a lyric, strophic form in colloquial Arabic. Interestingly,

many zajals share an aspect of musical structure with the Spanish cantiga, the Italian lauda, and the French virelai: in each, the melody of the refrain recurs as the closing section (vuelta)

of each stanza. This structure is widespread in traditional European

folk music, and appears in Arabic song only after the Muslim conquest of

Andalusia. The extent of Arabic influence on the music and poetry of

Europe is widely and hotly debated: here is one instance in which the

influence might just as easily have gone in the opposite direction.

muwashshahat and zajals

made up the bulk of the repertoire of young female singers who were

basically highly-prized slaves. These women were trained from childhood

in the memorization and performance of the sung poetic forms, and their

cultural and economic value increased according to their skill. When a

young woman was sold, her price was negotiated through examination of a

large volume that detailed the scope and nature of her repertoire. The

most highly-prized singers also brought to their employers an ensemble

of musicians, trained in the accompaniment of these pieces.

No music survives for the medieval muwashshah and zajal,

and, while medieval sources provide some descriptions of the poetry and

performance, they alone do not give enough information to reconstruct

the music. Here is a situation in which parallel musical traditions

become particularly important to the historical performer. The modern

Andalusian oral tradition, known and so identified throughout North

Africa (Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria), retains particularly strong and

immediate roots with its medieval Iberian ancestry, a retention attested

by the self-identification of modern players with the lineages of

medieval teachers. The connection is nearly as immediate in the

repertoire itself: many examples of muwashshah and zajal

in the modern Andalusian oral tradition adhere closely to the original

medieval texts, giving us a point of departure from which musical

reconstructions may be made. In this area, we are indebted to scholars

James Monroe and Benjamin Liu, whose book Ten Hispano-Arabic Songs in the Modern Oral Tradition (Berkeley, 1989) has been an invaluable resource for these musical realizations.

In

the fabled wine-parties of tri-cultural medieval Iberia, full

performances of these genres could last many hours. Therefore, while the

texts of the poems are given here in their deserved entirety, in some

cases we have chosen to present only two or three musical stanzas of a muwashshah.

Pronunciation

of medieval Iberian texts also requires special consideration:

pronunciation has changed greatly over the centuries, and varied

according to region and dialect. We thank Liljana Elverskog, Abdallah

Malik, Consuelo Lopez-Morillas, and Angel Saenz-Badillos for their

expert coaching in the spoken subtleties of these ancient languages.

—Altramar

1

References for such performance practice can be found as far back as

the thirteenth century; see James T. Monroe and Benjamin Liu, Ten Hispano-Arabic Strophic Songs in the Modern Oral Tradition (Berkeley, 1989) p.16.

1. Reshut: Lababi ya‛ireni kašo’el lašaharah

Levi Ibn al-Tabban (fl. late 11th century)

Source: Raymond Scheindlin, The Gazelle (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1991)

The

period from c1000-c1150CE is referred to as a Golden Age of Iberian

Jewish culture. Jewish scholars, poets, philosophers and scientists held

important official, cultural and advisory positions in both Muslim and

Christian courts.

During this Golden Age, Andalusian Jews introduced the practice of presenting poems called reshuyot,

as a preface to the standard prayers that occur between the preliminary

service and the morning service “proper”. These were, in effect, a

“beginning before the beginning”: intimate meditations sung by the

precentor, with their immediacy characterized by the consistent use of

the first person singular pronoun.

The reshuyot

typically incorporate Biblical diction, but also delight in poetical

wordplay: often the number of lines matches the number of letters in the

poet's given name; very often they incorporate an acrostic of the

poet's given name at initial of each line (as does the example presented

below).

In Arabic love lyric, the poet often spoke of the

gazelle as a metaphor for the Beloved; in Hebrew religious texts, this

was adapted to symbolize God or Israel. Ours is by Levi Ibn al-Tabban, a

grammarian and poet from Saragossa who wrote primarily liturgical

verse.

2. Cantio: Dum pater familias

Anonymous (12th century)

Source: Santiago de Compostela, Biblioteca de la Catedral (“Codex Calixtinus”)

In

the Middle Ages, Christians from Germany, France, Italy, and all over

western Europe made the pilgrimage to the Cathedral at Santiago de

Compostela, built over the grave of St James, Santiago, the patron saint

of Spain. The 12th century manuscript known as the Codex Calixtinus,

housed at the Cathedral Library, contains music associated with this

cathedral and the pilgrimage to it, and includes an observance of the

feast of St. James. Dum pater familias, a Latin cantio in

praise of the saint, comes from this collection. Its refrain

commemorates James, “first of the apostles”, martyred in Jerusalem.

3. Muwashshah: Raše ‛am ‛et hitassef

Yéhuda ha-Levi (1075-1141)

Source: Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Opp. Add 4°, 81

The Hebrew muwashshah

on our program is by Yehuda ha-Levi, renowned for his contribution to

sacred and secular poetry of Andalusia's Golden Age. The poem is a

cultural melange, containing Biblical references, vernacularized Hebrew,

and elements of Arabic and Romance speech, culminating in a Romance jarcha. It is a panegyric to “Joseph”, the identity of whom has been the subject of debate.

It

has been suggested that this is a poem of messianic redemption, and

that “Joseph” is a reference to a “secondary messianic figure”, Messiah

son of Joseph, who would precede the Davidic Messiah and reunite the

tribes of Israel.1 The poem may be read on multiple levels of

meaning, as both lauding a patron and intending a symbolic, messianic

message. Our melody is informed by melodic gestures found in 13th

century Hebrew Bible cantillation symbols, formed into rhythmic song

characteristic of the Andalusian muwashshah tradition.

1 H.P. Salomon “Yehuda Halevi and hid 'Cid'” (American Sephardi IX, 1978)

4. Cantiga #10: Rosa das Rosas

Anonymous (13th century), The Cantigas de Santa María

Source: El Escorial, Real Monasterio de El Escorial, B.1.2

The

court of Alfonso X El Sabio “The Wise” (1252-1284), king of Castile and

León, was one of the cultural centers of western Europe, drawing

scholars, artists, scientists, and musicians of diverse backgrounds and

faiths. The collection of Gallego-Portuguese songs known as the Cantigas de Santa Maria, a treasury of religious folk-legend, was assembled under Alfonso's direction. These cantigas

tell of the many miracles performed by the Virgin Mary. The largest

manuscript (El Escorial B.1.2, or “E1”) is filled with illuminations

that portray Christians, Arabs, and Jews, together and separately

playing an astonishing variety of musical instruments. Every tenth cantiga in this collection departs from the narrative miracle theme and instead presents an adoring song of Marian praise; our cantiga, Rosa das Rosas, is one of these.

5. Muwashshah: Ma li-l-muwallah

Ibn Zuhr (1113-1198)

Source: Sayyid Gazi Diwan al-Muwashshat al-Andalusiyya (Alexandria: Mansha‛at al-Ma‛arif, 1979)

When

Andalusian poet Ibn Zuhr was asked which of his muwashshahat was most

excellent, he chose this one. It is a poem of yearning, full of the

sensuous imagery beloved by medieval Iberian poets of all three

cultures, and used by them to evoke both earthly and spiritual love:

sweet wine, gardens, beautiful women, the crescent moon.

Our

musical arrangement is informed by medieval Arabic prose descriptions

and by contemporary Moroccan folk music approaches. In the original

manuscript, part of the final stanza is missing; for the purpose of

performance, we repeat text from the first verse, incorporating a change

in verb tense as utilized in the modern oral tradition. On the

recording, you will hear the first and last stanzas and the jarcha. The entire text is presented below.

6. Canso: Dona si totz temps vivia

Berenguer de Palol (a.k.a. Berenguier de Palazol; fl. early 12th century)

Source: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, f. fr. 22543 (Troubadour ms. “R”)

The eleventh and twelfth century poet-musicians known as trobadors flourished in southern France and in neighboring Catalonia, itself a part of the Iberian culture. Much of the trobadors'

poetry, written in the language of Old Occitan, is an expression of the

“art of courtly love”, an idealized system of cultural and social

behavior between noble women and men that developed over a period of

time in Europe, with antecedents in the Middle East. The courtly lover

views himself as the servant of the beloved; love is often either

unrequited, or in some way illicit (it was common, for example, for the

lady to be married to someone else). Yet through suffering and rejection

the lover's situation becomes elevated to an almost mystical state in

which he is ennobled or illuminated by this experience of transcendent

devotion.

In the thirteenth century, the culture that had inspired the art of the trobadors was nearly destroyed by the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathar heresy; but the trobadors' influence spread far and wide, to the northern French trouvères, to the German minnesänger, to Dante and the Italian poets of the dolce stil nuovo, and beyond.

Dona, s'ieu tostems vivia is by one of the first Catalan trobadors, Berenguer de Palol, whose vida,

or biography, tells us that he was the “son of a poor knight”. Only

eight of the twelve extant songs by Berenguer have survived with their

melodies intact.

7. Cantiga de amigo: Eno sagrado en Vigo

Martim Codax (fl. c.1230)

Source: Pierpont Morgan Library, Vindel MS M979

The Gallego-Portuguese cantiga de amigo

is one of the Iberian peninsula's oldest vernacular poetic forms. The

words are most often expressed from the point of view of a woman; this

suggests that the cantigas de amigo may derive from a very old tradition of vernacular women's song.

Many of the cantigas'

recurring themes — yearning for a distant lover, confiding in a mother

or sister — are shared with women's songs from the Sephardic oral

tradition, and also with the jarchas (which were known to have

been “borrowed” from pre-existing sources). While it is impossible to

conclusively identify certain Sephardic women's songs as “medieval”,

this shared imagery suggests possible connections across genres.

Few of the melodies of the cantigas de amigo

have survived. The seven cantigas de amigo by the Gallician troubadour

Martim Codax are a notable exception: all but one are notated, and it is

that cantiga, written under an empty staff with no notes, which

we have chosen. The melody was arranged by Jann Cosan and Altramar on

the basis of the existing cantiga melodies.