medieval.org

anonymous4.com

Harmonia Mundi HMU 90 7156

1995

2008: Miracles of Compostela

Harmonia Mundi "Gold" 507156

medieval.org

anonymous4.com

Harmonia Mundi HMU 90 7156

1995

2008: Miracles of Compostela

Harmonia Mundi "Gold" 507156

1. Invitatory. Venite omnes cristicole [1:16]

cc 25

[a beato calixto papa edita]

2. Processional. Salve festa dies [4:38]

cc 70

versus calixti pape cantandi a processionem sancti iacobi in solempnitate passionis ipsus et transalacionis eiusdem

3. Benedicamus trope. Vox nostra resonet [1:41]

cc 102

magister iohannes legalis

4. Invitatory. Regem regum dominum [0:50]

cc 1

a domno papa calixto ex evangelis edita

5. Benedicamus trope. Nostra phalanx plaudat leta [2:26]

cc 95

ato episcopus trecensis

6. Antiphon. Ad sepulcrum beati Iacobi [2:13]

cc 16

ad vesperas, verba calixti

7. Benedicamus trope. Ad superni regis decus [3:05]

cc 98

magister albericus archiepiscopus bituricensis

8. Brief responsory. Iacobe servorum [2:13]

cc 60

9. Benedicamus domino [1:54]

cc 112

magister gauterius de castello rainardi

10. Conductus. In hac die laudes [4:29]

cc 82

conductum sancti iacobi a domno fulberto karnotensi episcopo editum

11. Kyrie trope. Cunctipotens genitor [5:14]

cc 111

gauterius prefatus

Chant

form Bibliotèque nationale, Paris, ms. Lat 1112, with cadence formulas

modified to match those of the polyphonic setting in Jacobus

12. Hymn. Psallat chorus celestium [1:10]

cc 2

hymnus s iacobi a domno fulberto karnotensi episcopo editus

13. Prosa. Alleluia. Gratulemur et letemur [6:27]

cc 76

prosa sancti iacobi latinis, grecies et ebraicis verbis, a domno papa calixto abbreviata

14. Offertory. Ascendens Ihesus in montem [3:48]

cc 77

[Calixtus?]

15. Agnus dei trope. Qui pius ac mitis [2:24]

cc 93

agnus fulberti episcopi karnotensis

16. Benedicamus trope. Gratulantes celebremus festum [2:47]

cc 97

magister goslenus episcopus suessionis

17. Conductus. Iacobe sancte tuum [5:01]

cc 80

conductum sancti iacobi ab antiquo episcopo boneventino editum

18. Responsory. O adiutor omnium seculorum [8:36]

cc 106

magister ato episcopus trecensis

quidam antistes a iherosolimis rediens, ereptus per beatum iacobum a marinis pericul, in primo tono edidit hunc responsorium

19. Prosa. Portum in ultimo [2:42]

cc 107

prosa idem ato

20. Benedicamus trope. Congaudeant catholici [3:38]

cc 96

magister albertus parisiensis

21. Prosa. Clemens servulorum [4:49]

cc 78

prosa s iacobi crebro cantanda a domno guilelmo patriarcha iheroslimitano edita

ANONYMOUS 4

Ruth

Cunningham

Marsha Genensky

Susan Hellauer

Johanna Maria Rose

harmonia mundi usa (P C) 1995

Recording: July 25-28, September 20-22,1995, Campion Center, Boston, MA

Producer: Robina G. Young

Engineer: Brad Michel

Editing: Paul F. Witt

· Cover recto: Detail, showing St. James,

of twelfth-century frontal in the Museo Catedralicio, Orense, Spain;

photograph by Juan Manuel Moretón Brasa

· Cover verso: Fourteenth-century panel painting

by anonymous Catalan-Aragonese artist,

“Translation of the Body of Sant'Iago”

courtesy of Prado, Madrid, Spain

· Three illuminated letters from the Codex Calixtinus

reproduced from

José López-Calo, S.J., La música medieval en Galicia

(La Coruña, 1982); photographs by Constantino Martínez

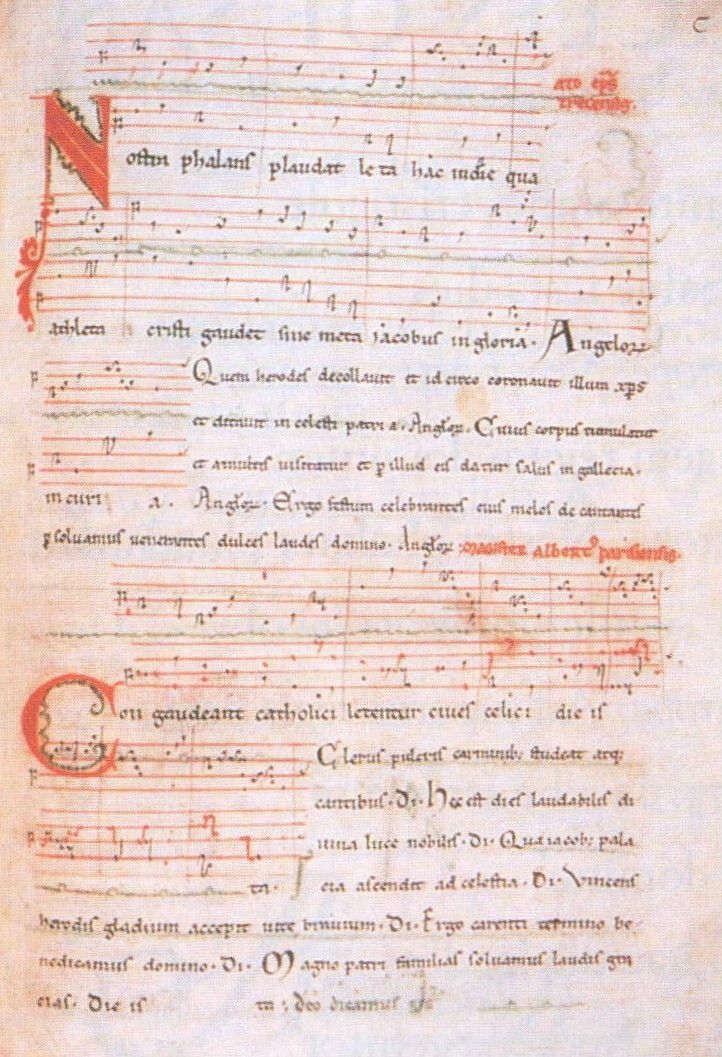

· Codex Calixtinus, fol. 185 recto: Nostra phalanx & Congaudeant catholici

(Reproduced from the facsimile edition published by

Fotojae and the Centro de Estudios del Camino de Santiago;

photograph by courtesy of UCLA Music Library)

· Forster Book of Hours: Donor with St. James as Pilgrim (c. 1500)

(Courtesy of Victoria & Albert Musem and e.t. archive)

Photo Anonymous 4: Christian Steiner

Booklet design: Steven Lindberg

— Marilyn Stokstad, Santiago de Compostela: In the Age of the Great Pilgrimages

Copyright copy 1978 by the University of Oklahoma Press

During

the Middle Ages, three holy places — Jerusalem, Rome, and Compostela, a

remote Galician village in northwestern Spain — were visited by

countless pilgrims from all over Europe, often in fulfillment of a

lifelong dream. Compostela was the legendary burial place of St. James

the Greater, Jacobus Major, the first apostle, and the first to

die a martyr. For medieval Spain, under Moslem siege, St. James became a

heavenly champion and symbol of the Christian Reconquista. His

power as a miracle worker was renowned, and visitors to his tomb sought

both physical and spiritual healing, as they do to this day.

Since the late twelfth century the Cathedral of Santiago in Compostela has possessed a manuscript entitled Jacobus (and also called Liber Sancti Jacobi or Codex Calixtinus).

Its five books contain sermons on St. James, chants and lessons for his

feasts, accounts of his miracles and legends, an epic tale of

Charlemagne in Spain, an informative travel guide to the pilgrimage

routes through France and Spain, and a contemporary “supplement” of

polyphonic music. How it found its way to Compostela is not known for

certain, but it is undoubtedly a French product, probably compiled or

written in Cluny around 1150. Although its author was obviously erudite,

Jacobus contains many ridiculous errors in grammar, rhetoric,

and dogma, which scholars have tried for centuries to rationalize. It

has recently been shown that the non-musical portions containing these

errors were actually texts to be corrected by French schoolboys as

Latin exercises, and that the music (which is not defective) was meant

to be sung by the boys on feasts of St. James.*

About ninety percent of the music in Jacobus

is plainchant for the Vigil and Feast of St. James (25 July) and for

the Translation of his body from Palestine to Galicia (30 December).

Most of it is specifically liturgical: hymns, antiphons, responsories,

and versicles for the Divine Office and Mass propers and ordinaries.

Many, if not most, of these were contrafacts (i.e., adapted from

existing chants), such as the invitatory antiphons Venite omnes and Regem regum, the processional hymn Salve festa dies, and the antiphon Ad sepulcrum beati Iacobi. Other chants, like Agnus dei: Qui pius ac mitis,

were expanded, or “troped” with additional text and music, and it was

perhaps as an educational gesture that Greek, Hebrew, and Galician words

were added to the ancient double-versicle “prosa” Alleluia: Gratulemur et letemur.

Although they represent a mere ten percent of the music in Jacobus,

the polyphonic works (nineteen for two voices, one for three voices)

have received more attention from scholars than the plainchant has

because they are among the earliest such pieces to have been written

down. Some, like the conductus In hac die and Jacobe sancte tuum,

are not strictly liturgical, but are perhaps meant to accompany a

reader’s walk to the lectern. Several others are settings or tropes of

the Benedicamus domino, a closing formula of the Office and Solemn Mass, such as Vox nostra resonet, Nostra phalanx, Ad superni regis, Gratulantes celebremus, and Congaudeant catholici.

This last piece was originally notated in two voices, with a third

voice added in a different hand — making it one of the earliest

surviving three-voice pieces. Because this third voice creates many

dissonances, some scholars say that only two voice parts should be sung

at a time. We think, however, that it makes a very satisfying

three-voice piece, just daring enough for an “avant-garde” work of its

time.

Most of the musical works in Jacobus are attributed

in the manuscript to specific (usually French) authors — clerics and

other notables, some famous and others unknown. Until recently it was

thought that these attributions were fanciful, but research has verified

many of them. For plainchant works based on existing melodies, these

authors probably wrote new texts, often drawn from St. James’s copious

miracle literature rather than from scripture. For polyphonic works,

these authors may have been responsible for the music and text, or for

the music alone. The greatest number of polyphonic settings by a single

composer, including the monumental responsory O adiutor and its trope Portum in ultimo, are those of Bishop Ato of Troyes, who retired to Cluny in 1145 — just about the time when Jacobus was assembled.

There

are two distinct textures for the polyphonic works: a “discant” style,

in which the two voice parts generally move together (as in the

conductus and the Benedicamus tropes), and an “organal” style in which

the upper voice part sings a rhapsodic melody against the long-held

notes of a lower tenor voice based on a liturgical chant (as in O adiutor and the troped Kyrie: Cunctipotens).

The plainchants most commonly set in this way are the soloists’

portions of the Gradual and Alleluia of the Mass, and the Matins

Responsory of the Divine Office. In hindsight, it is possible to see

this style, with its relatively simple textures and limited liturgical

repertoire, as a primitive precursor of more sophisticated developments

to come. But the polyphonic compositions that survive in Jacobus are representatives of a highly developed musical language. Just about a generation after the appearance of Jacobus,

the basic elements of this language — its vocal textures and its

repertoire — came together again in the first Notre Dame school of

sacred polyphony, led by Leoninus.

The notation in Jacobus

is ambiguous as to rhythm and meter, as well as to alignment of pitches

between the voice parts in the polyphony. Scholars have proposed a

variety of rhythmic solutions for the polyphony and the non-liturgical

songs, ranging from an unmeasured chant-like style to strictly regular

“modal” rhythm. Instead of adhering to any previously existing theory,

we have come to our rhythmic interpretations by considering not only

melodic, harmonic, and notational patterns, but also the nature and

poetic structure of the texts themselves. In imitation of contemporary

instrumental practice, we have occasionally added vocal drones as well.

As our guiding principle we have tried to be true to the infectiously

joyful and exuberant melody that pervades this remarkable collection,

made for and performed by the young treble voices of a medieval French

grammar school.

— Susan Hellauer

* Christopher Hohler, “A Note on Jacobus”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, XXXV (1972), pp. 31-80.