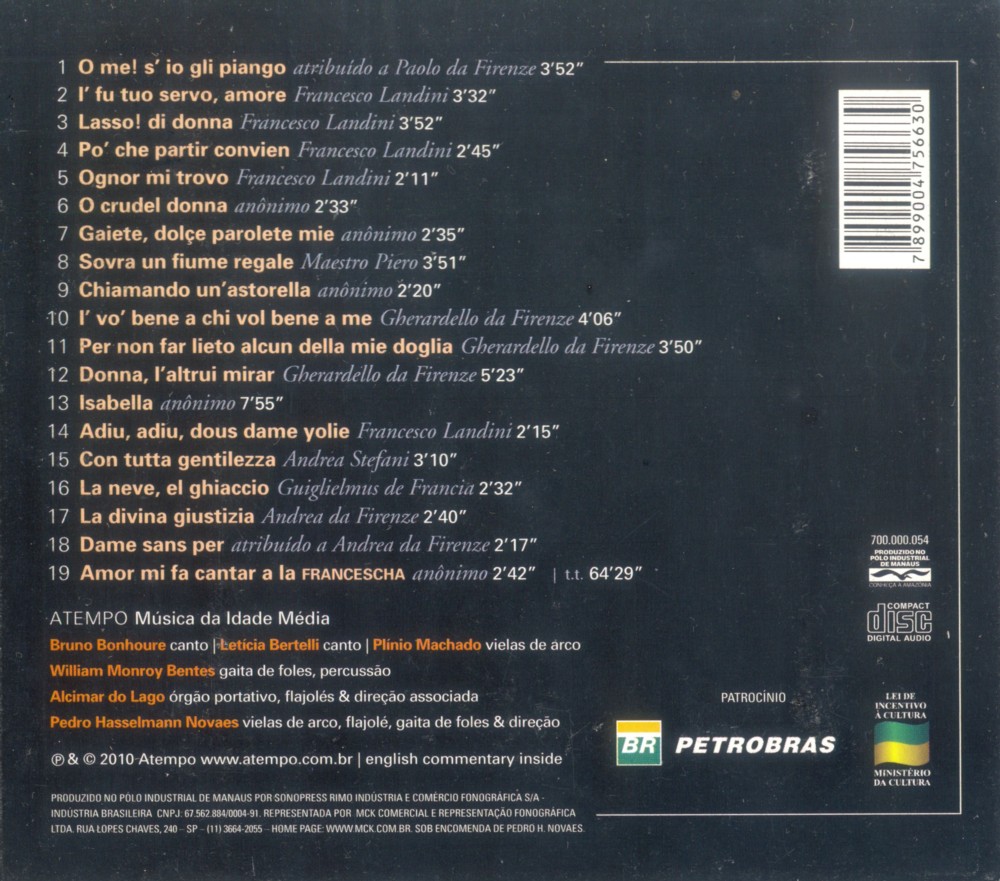

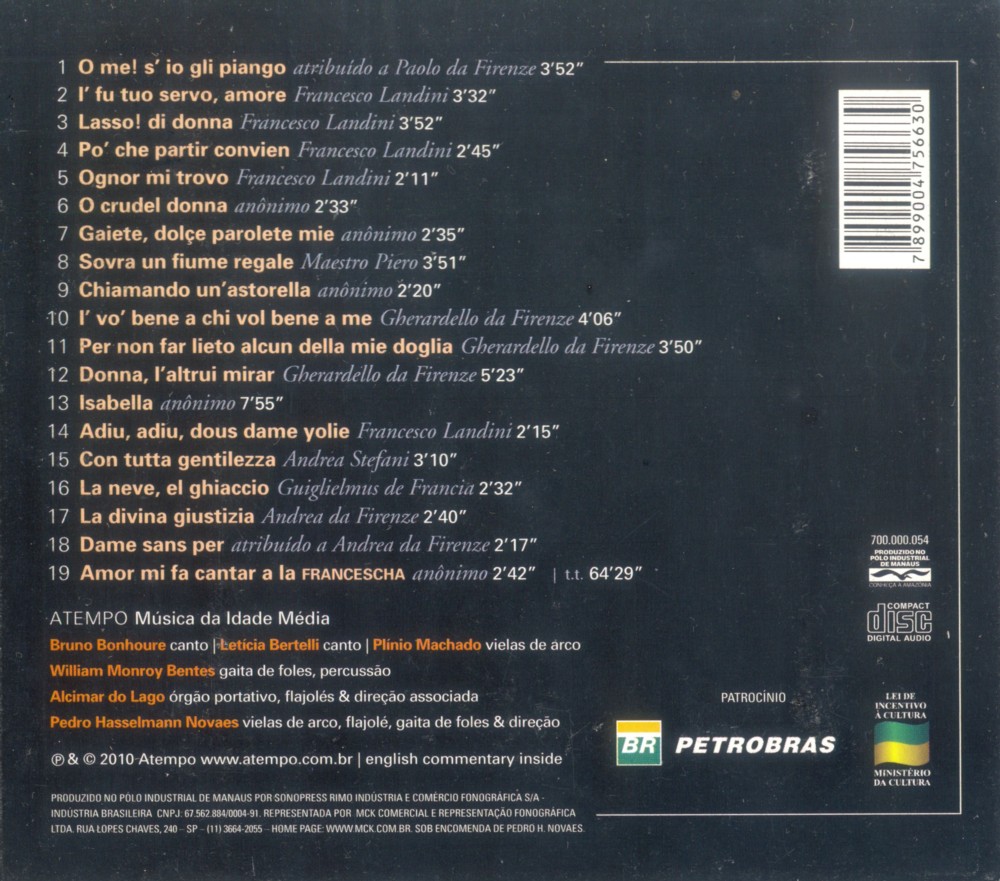

Estilo novo, nova arte / Atempo, Música da Idade Média

Polifonia de Florença e Verona do século XIV

Atempo AA0002000

2010

Atempo, Música da Idade Média

Estilo novo, nova arte

Polifonia de Florença e Verona do século XIV

Fourteenth century polyphonic music from Florence and Verona

a ADOLFO BROEGG

amigo que continua a formar e iluminar gerações

1. O me! s'io gli piango [3:52] ballata,

atribuído a Paolo da Firenze (ca. 1355-1436)

canto LB BB, vielas de arco PN PM, órgão portativo AL

Francesco LANDINI (ca. 1325-1397)

2. I' fu tuo servo, amore [3:32] ballata

flajolé em bambú PN, viela de arco PM, guimbarda AL, pandeireta WB

3. Lasso! di donna [3:52] ballata

canto BB, flajolé em bambú PN, viela de arco PM, órgão portativo AL

4. Po' che partir convien [2:45] ballata

canto LB, vielas de arco PN PM, órgão portativo AL

5. Ognor mi trovo [2:11] ballata

canto LB, vielas de arco PN PM, pandeireta WB

6. O crudel donna [2:33] madrigal,

anônimo

flajolés em bambú PN AL

7. Gaiete, dolçe parolete mie [2:35] rondello,

anônimo

canto LB BB

8. Sovra un fiume regale [3:51] madrigal,

Maestro Piero (nasce antes de 1300; morre após 1350)

flajolés em bambú AL PN

9. Chiamando un'astorella [2:20] madrigal,

anônimo

canto LB BB, tamboril WB

Gherardello da FIRENZE (ativo em 1320; morre entre 1362 e 1363)

10. I' vo' bene a chi vol bene a me [4:06] ballata

gaitas de foles PN WB

11. Per non far lieto alcun della mie doglia [3:50] ballata

canto LB BB, vielas de arco PN PM, órgão portativo AL

12. Donna, l'altrui mirar [5:23] ballata

canto LB, viela de arco PN

13. Isabella [7:55] stampitta,

anônimo

flajolés em bambú PN AL

14. Adiu, adiu, dous dame yolie [2:15] virelai,

Francesco Landini

canto BB, viela de arco PM, órgão portativo AL

15. Con tutta gentilezza [3:10] ballata,

Andrea Stefiani (ativo em 1399)

vielas de arco PM PN, órgão portativo AL

16. La neve, el ghiaccio [2:32] madrigal,

Guiglielmus de Francia (?) / texto de Franco Sacchetti

canto LB, viela de arco PM

17. La divina giustizia [2:40] ballata,

Andrea da FIRENZE (ativo em 1375; morre em 1415)

viela de arco PN, órgão portativo AL

18. Dame sans per [2:17] ballade,

atribuído a Andrea da FIRENZE

canto BB, órgão portativo AL

19. Amor mi fa cantar a la FRANCESCHA [2:42] ballata,

anônimo

canto LB BB, vielas de arco PN PM, órgão portativo AL, pandeireta WB

Atempo

Música da Idade Média

Bruno Bonhoure (BB) —

canto / voice

Leticia Bertelli (LB) —

canto / voice

Plinio Machado (PM) —

vielas de arco / medieval fiddles

William Monroy Bentes (WB)

pandeiretas / tambourines •

tamboril / side drum •

gaita de foles / bagpipes

Alcimar do Lago (AL)

órgão portativo / portative organ •

flajolés em bambfi / bamboo flageolets •

guimbarda / mouth harp

direção associada / associated direction

Pedro Hasselmann Novaes (PN)

vielas de arco / medieval fiddles •

flajolé em bambú / bamboo flageolet •

gaita de foles / bagpipes

direção / direction

O

conjunto Atempo, dedicado à música da Idade Média, foi criado em 1992

e, desde então, tem atuado ativamente no panorama de música antiga no

Brasil. O CD O Trovador da Virgem (Sono-Viso Vozes), lançado em

2001 com um programa dedicado ao famoso repertório galaico-português das

Cantigas de Santa Maria, obteve criticas positivas, inclusive de

revistas especializadas.

The ensemble Atempo, dedicated to the

music from the Middle Ages, was created in 1992 and, since then, has

been active in the Brazilian early music panorama. The CD O Trovador da Virgem

(Sono-Viso Vozes), appeared in 2001 with a program dedicated to the

famous Galician-Portuguese repertoire Cantigas de Santa Maria, and

received positive recommendations, including some from specialized

magazines.

GRAVAÇÃO

Realizada entre 10-13 de novembro e 14-16 de dezembro de 2009, no Palácio de São Cristóvão, sede do Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (na área de exposição permanente — "Sala da Baleia" e "Sala da Preguiça"), Rio de Janeiro.

MIXAGEM, EDIÇÃO E MASTERIZAÇÃO

Realizadas entre janeiro e abril de 2010 no Estúdio da Orquestra de Bolso Produções Artísticas, Rio de Janeiro.

ENGENHEIRO DE GRAVAÇÃO, MIXAGEM, EDIÇÃO E MASTERIZAÇÃO —

Eduardo Monteiro

TRADUÇÃO DAS LETRAS E VERSÃO DO LIVRETO PARA 0 INGLÊS —

Sergio Pachá

DESIGN GRÁFICO —

Marcellus Schnell

ILUSTRAÇÃO DA CAPA —

"Retábulo de Évora" (detalhe)

pintor anônimo (Bruges), c.1490 ·

Museu de Évora (Portugal)

FOTO DO GRUPO —

Khaï-Dong Luong

PRODUÇÃO —

Hermano Shigueru Taruma e Pedro Hasselmann Novaes

PATROCÍNIO —

PETROBRAS |

LEI DE INCENTIVO À CULTURA /

MINISTÉRIO DA CULTURA

EDIÇÕES UTILIZADAS

— Marrocco, W. Thomas (ed.). Italian Secular Music by Vincenzo da Rimini, Rosso de Chollegrana, Donato da Firenze, Gherardello da Firenze, Lorenzo da Firenze (Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century VII). Editions de LOiseau-Lyre, Monaco, 1971 (11).

— Marrocco, W. Thomas (ed.). Italian Secular Music (Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century XI). Editions de L'Oiseau-Lyre, Monaco, 1978 (1).

— Pirrotta, Nino (ed.). The Music of Fourteenth Century Italy (Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae 8/1). American Institute of Musicology, Amsterdam, 1954 (10, 12).

— Pirrotta, Nino (ed.). The Music of Fourteenth Century Italy (Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae 8/I). American Institute of Musicology, [s.l.], 1960 (6, 7, 8, 9, 19).

— Pirrotta, Nino (ed.). The Music of Fourteenth Century Italy (Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae 8/V). American Institute of Musicology, [s.l.], 1964 (15, 16, 17, 18).

— Schaik, Martin van & Schima, Christiane (ed.). Instrumental music of the Trecento - A critical edition of the instrumental repertoire of the Manuscript London, British Library, Add. 29987. STIMU - Foundation for Historical Performance Practice, Utrecht, 1997 (13).

— Schrade, Leo (ed.). The Works of Francesco Landini (Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century IV). Editions de L:Oiseau-Lyre, Monaco, 1958 (2, 3, 4, 5, 14).

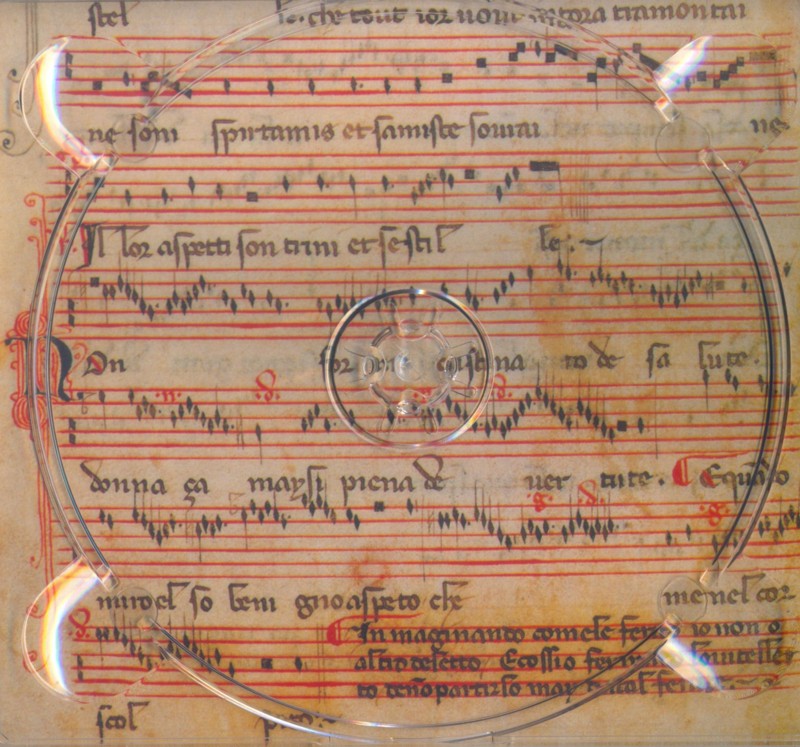

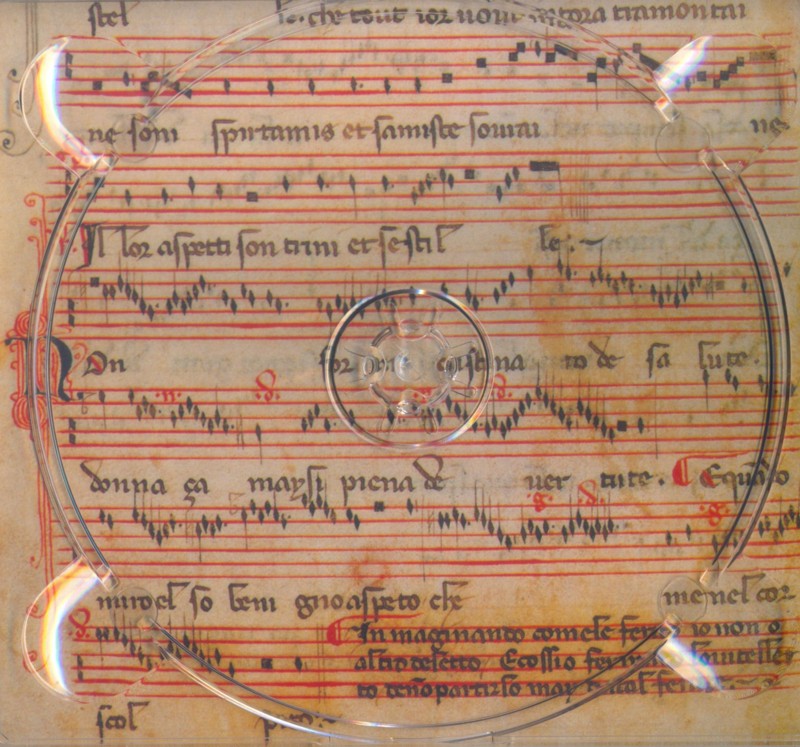

FONTES PRIMÁRIAS DAS COMPOSIÇÕES

• Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds italien 568, Pit (1).

• Florença: Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Palatino 87 [Códice

Squarcialupi] (2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 14, 17).

• Roma: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rossi 215 (6, 7, 9, 19).

• Florença: Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Panciatichiano 26 (8).

• Londres: British Library, Additional 29987 (13, 16).

• Lucca: Archivio di Stato 184 [Códice Mancini] (15).

• Modena: Biblioteca Estense e Universitaria a.M.5.24 [Latino 568; olim IV.D.5] (18).

AGRADECIMENTOS

Adauto Novaes, Agostinho Resende Neves, Clotilde Hasselmann,

Jose Miguel Wisnik, Katiane Borghesan Reis, Khaï-Dong Luong,

Kristen Christensen, Maria Lúcia Rangel & Sérgio Augusto,

Martha Carolina Bernabe Novaes, Maurício Dottore

Thiago Hasselmann Novaes, Veruschka Bluhm Mainhard

Ao Museu Nacional em nome do seu então diretor, Sergio Alex Kugland de Azevedo

e da então chefe da Serão de Museologia, Rachel Correa Lima

℗ & © 2010 Atempo

English liner notes

Em 1301, Dante Alighieri liderou uma delegação política a Roma para

descobrir quais eram as intenções da cúria do Papa Bonifácio VIII, que

vinha intervindo nos destinos da Toscana. Retido, recebeu a noticia de

que fora considerado proscrito por Florença, e um conjunto de eventos e

decisões determinaria que jamais voltasse em vida à sua cidade natal.

Dante dava, então, inicio ao seu périplo por casas e cortes italianas,

canalizando energia para escrever a Comédia — denominada Divina

por Boccaccio, um de seus primeiros comentadores. Nessa fase, um dos

refúgios do poeta foi a corte da família Della Scala de Verona, que o

hospedou duas vezes — um de seus patronos, Cangrande I, figura em sua

obra máxima (Paraíso, )(VII, 76).

Essas passagens da biografia de Dante conduzem a reflexões sobre

a arte e o patronato em Florença e em Verona no século

XIV.

Analogamente, este álbum é dedicado à música polifônica do Trecento

de Florença e do Veneto — muito provavelmente da mencionada corte

veronesa dos Della Scala —, algumas gerações posteriores ao poeta.

E

como diferiam as duas cidades! Florença não dispunha de uma corte

central, sendo os poderes divididos principalmente entre prósperos

comerciantes e a Igreja. Verona, mais senhorial, estava nas mãos dos

Della Scala por mais de um século.

Para nosso proveito, a prática da polifonia de Florença e

de Verona também foi muito contrastante. O Veneto, berço

da Ars Nova

musical na Itália, adotaria o madrigal com notação musical e feições

autóctones; já a Toscana, algumas décadas depois, absorveria muitos

elementos da estética e escrita francesas, fazendo da ballata o seu carro-chefe.

O

estreitamento cultural entre Toscana e França decorreria, em parte, do

continuo comercio internacional entre bancos e manufaturas têxteis da

regido. Ilustra isso o conflito deflagrado em 1378 entre o Cardeal Piero

Corsini e as autoridades laicas florentinas, implicando a deserção de

Corsini e seu séquito para o campo francês, destinos à corte do papado

em Avignon. Esse movimento originou-se da ruptura do Colégio de

Cardeais, logo que Urbano VI foi consagrado em um contexto de grande

pressão pela escolha de um pontífice italiano, depois de um longo exílio

da corte papal em Avignon (1309-78). Os cardeais franceses e seus

simpatizantes deram inicio, então, a um processo paralelo, elegendo

Clemente VII. Era a eclosão do Grande Cisma (1378-1417), resultando

inicialmente na coexistência de um papa em Roma e outro em Avignon. O

Cardeal Corsini vinha de uma família conservadora e influente, e seus

seguidores contavam, em sua maioria, com parentes burgueses

consideravelmente interessados na economia francesa.

No Trecento,

a vida intelectual e artística de Florença pôde prosperar em uma casa

laica e outra religiosa, vinculadas de alguma forma à França. Os

Alberti, banqueiros florentinos — muitíssimo influentes na Europa, na

segunda metade do século XIV —, mantinham negócios em Paris e Avignon.

Já o convento agostiniano do Santo Spirito, que crescia em reputação na

primeira metade do século XIV, abrigou uma academia livre, e era tão

ativo quanto independente da Igreja e da Universidade.

Vínculos

com a Igreja eram indícios constantes nas biografias dos compositores

florentinos do século XIV. Eles estavam entre os muitos frades,

capelães, monges-músicos de suas gerações. Alguns eram simplesmente

organistas, mas fosse por renome, influencia ou acaso, parte de suas

obras foi-nos legada ao passar da tradição oral para o registro escrito.

Trabalharam em igrejas ou casas monásticas. Contudo, as fontes musicais

da Ars Nova são, essencialmente, compilações de músicas

seculares, e o seu tema central, o Amor. A julgar pelos fatos citados

sobre a ascendência francesa na sociedade florentina, não seria de

estranhar que a música sofresse, analogamente, infiltrações estéticas. E

foi o que aconteceu, a começar, pela coincidência da ballata com virelai ou a chanson balladée (formas musicais fixas idênticas e com refrão). Por volta de 1370, a ballata

era o gênero prevalente entre os polifonistas florentinos. Segundo

Michael Long, esses músicos, na segunda metade do século XIV,

consideravam-se herdeiros da tradição francesa no campo da teoria

musical, preferindo Phillippe de Vitry a Marchettus de Padua.

Marchettus, que lecionou nas universidades de Pádua e Bolonha, veria o

seu sistema de notação musical amplamente adotado no Veneto, mas

proibido aos estudantes em Florença.

A ballata O me! s' io gli piango abre o álbum. Ela é atribuida a Paolo da Firenze, também conhecido como Dom Paolo tenorista,

devendo o tratamento ao fato de ter sido monge (chegando a abade), e a

alcunha às suas habilidades de compositor. Estava entre os uomini di stato

de Florença, ou seja, aqueles que exerciam liderança na vida pública.

Nessa condição, foi delegado eclesiástico no Concilio de 1409, realizado

em Pisa — vizinha e rival histórica de Florença. Legou-nos mais de 50

composições, ballate em sua maioria, cujos estilos

perpassaram a tradição e a vanguarda. Foi retratado com o hábito negro

beneditino no mais completo e luxuoso manuscrito musical da Ars Nova

italiana, o códice Squarcialupi, fonte que Paolo teria ajudado a

compilar em princípios do século XV, pouco antes de morrer, octogenário.

Chegaram a ser tragadas as pautas para as suas composições, que

misteriosamente ficaram vazias; o manuscrito 568 do fundo italiano da

Biblioteca Nacional de Paris, mais modesto, é a fonte primária única de O me!.

Villa Paradiso foi o nome dado a um idílio proto-humanista pelo cronista Giovanni da Prato em Il paradiso degli Alberti (1389). Nesta romanza, personagens mais reais do que ficcionais — em contraponto ao Decameron

de Boccaccio — protagonizam eventos diários nos jardins da casa dos

Alberti. Uma passagem é digna de nota: "[...] para o prazer de todos, e

especialmente de Francesco, duas donzelas dançaram e cantaram seu Orsun gentili spiriti

com tal doçura, que não apenas as pessoas da audiência foram afetadas,

mas ate mesmo os pássaros nos ciprestes começaram a cantar mais

docemente". O Francesco de que se trata é Landini, natural de Fiesole,

nos arredores de Florença. Filho de um pintor da escola de Giotto e

educado nas artes liberais, conviveu com a cegueira adquirida na

infância e conquistou renome como organista, poeta e compositor. Il

divino foi um epíteto raro, conferido a Dante e Michelangelo e também a

Landini, e talvez contribua para dimensionar o reconhecimento de sua

arte para os italianos.

As faixas 2 a 5 encerram uma seção de ballate de Landini, escritas a duas ou três vozes. Inicia-se com I' fu tuo servo, em versão instrumental, servindo de prelúdio para o bloco. Lasso! di donna, Ognor mi trovo e Po' che partir convien

seguem de perto certas convenções da poesia do amor cortés, mais

vocativa do que narrativa, confessional e reveladora dos estados da

alma. Lasso! di donna descreve a angústia de um amor

inexorável por uma mulher cruel. Contrariando o senso comum, sabe-se que

os trovadores, séculos antes, tinham todo o direito de endereçar versos

desconfiados às amadas, direito esse amplamente exercido em terras

meridionais e na Peninsula Itálica, a exemplo de outras ballate do nosso programa.

As faixas 2 a 5 encerram uma seção de ballate de Landini, escritas a duas ou três vozes. Inicia-se com I' fu tuo servo, em versão instrumental, servindo de prelúdio para o bloco. Lasso! di donna, Ognor mi trovo e Po' che partir convien

seguem de perto certas convenções da poesia do amor cortés, mais

vocativa do que narrativa, confessional e reveladora dos estados da

alma. Lasso! di donna descreve a angústia de um amor

inexorável por uma mulher cruel. Contrariando o senso comum, sabe-se que

os trovadores, séculos antes, tinham todo o direito de endereçar versos

desconfiados às amadas, direito esse amplamente exercido em terras

meridionais e na Peninsula Itálica, a exemplo de outras ballate do nosso programa.

Entre os séculos XIV e a primeira metade do século XV, o italiano que

desejasse discorrer sobre a causalidade amorosa, elogiar os seus

patronos — fosse ele "grande senhor ou pequeno tirano" —, investir

contra seus inimigos, chegando a sentenças moralizantes, seria

aconselhado a escolher o madrigal como meio de expressão. No madrigal, o

discurso construía-se sobre uma narrativa alegórica, subtextual,

trazendo a vantagem de resguardar o próprio autor.

O madrigal

também era um recurso recorrente nos duelos artísticos, atrações nas

cortes italianas do século XIV. Os adversários mostravam, a uma só vez,

suas qualidades de poeta, compositor e cantor ou instrumentista. Sabe-se

que Jacopo da Bologna, Giovanni da Cascia, Maestro Piero, atuantes em

cortes do norte, e também Francesco Landini, instruido por Jacopo se

confrontaram em várias oportunidades. O cronista Fillippo Villani narra

uma contenda datada de 1364, em Veneza. O júri contava com o velho

Petrarca. No final, Landini viria a receber os louros das mãos do Rei de

Chipre, Pedro, o Grande, mas Francesco Pesaro, de São Marco, seria

considerado o melhor organista da disputa, apesar do notório virtuosismo

instrumental de Landini. De qualquer forma, o feito do "organista de

Florença" não cairia no esquecimento: em uma iluminura de um quarto de

página, Landini e retratado com o laurel no códice Squacialupi. Em suma,

as virtudes improvisatórias e de virtuosismo poético e musical postas à

prova revelavam um meio competitivo. Nino Pirrotta avalia que era parte

do jogo exaltar seus próprios méritos e desdenhar daqueles dos rivais.

Não se sabe a quem se endereçavam os versos do madrigal I' me son un che per le frasche andando

de Jacopo da Bologna, mas eis a ironia da sentença de seu dístico

final: "corvo che di paon veste la penna / fra' papagal in vergogna si

spenna" [corvo que de pavão enverga as penas / entre papagaios, vexado,

se depena].

Composições do Veneto, provavelmente originadas em

Verona, na corte dos Della Scala, sobreviveram no códice vaticano Rossi

215. São os primeiros madrigais documentados e apresentam-se na forma de

dueto vocal, em sua maioria. Neles, Amor e Natureza são alegoricamente

associados; "por florestas, caminhos, campos, portos" e perseguido o

Amor, que foge em forma de pássaro no madrigal Chiamando un'astorella,

nona faixa deste album. Neles, a caça, o incêndio, o temporal e as

onomatopeias decorrentes da narração são eventos comuns e familiares,

mas existe um traço particular nos madrigais e ballatte

norte-italianos, inclusive do códice Rossi: um "estilo rapsódico", na

denominação de Pirrotta. Certos elementos desse estilo, evidenciados na

relação música e texto, dificilmente passam despercebidos.

Tres madrigais e um rondello — raro e arcaico para o Trecento

—perfazem uma seção norte-italiana (faixas 6 a 9). No repertório

escolhido, é comum a recitação do texto fazer-se sob ritmos marcados

entre a primeira voz — o superius—, muito ornamentada, e a segunda — o tenor

—, pronta a sacrificar uma potencial independência polifônica em favor

de um impacto musical teatralizado, soando a improviso. Essa percepção e

acentuada pelas eventuais sequências de intervalos musicais paralelos.

Sobre a ocorrência comum de intervalos melodicamente aumentados, note-se

uma passagem do madrigal Chiamando un'astorella,

na qual o movimento ascendente cadencial do tenor coincide

com a palavra voar (ou esvoaçar) no seguinte verso:

"Nel cor doneça e per la gabia vola"

(domina com o coração e pela gaiola esvoaça).

Ainda comuns são os recursos retóricos de

reiteração e interpolação de palavras ou

expressões. A seção mais aguda e final de Sovra un fiume regale,

madrigal de Maestro Piero (faixa 8, em versão instrumental),

é um exemplo: "Anna, mio cor, Anna, la vita mia".

Versos de uma ballata anônima, Occhi piançete,

são lembrados por Nino Pirrotta por razões análogas: " [...] (et) con dolorose pene / da la donna

reale esser privato (oimè privato)".

Muitas referencias à música e à dança acompanham os contos de Decameron de Boccaccio (c. 1350), próximos em espaço e tempo aos primeiros sinais de atividade musical da Ars Nova

na Toscana. As fábulas descrevem um ambiente erótico e libertino,

germinado nas colinas de Fiesole, nos arredores de Florença, para onde

seus personagens, dez jovens aristocratas fogem da Peste Negra (1348-50)

que assola todo o Ocidente. Li, Dioneo tange o alaúde e Fiametta, a

viela, no inicio da primeira jornada; a cornamusa (gaita de foles) de

Tindaro soa na conclusão da sétima.

Em Florença, superando a Peste, Gherardello foi capelão da então catedral Santa Maria Reparata. Suas ballate

estão entre as mais próximas de uma creditada origem popular. São todas

monofônicas — uma única linha melódica original — e especialmente

ornamentadas. Outro compositor de mesma geração, Lorenzo Masini, musicou

o poema de Boccaccio na ballata Non so qual mi voglia, também monofônica.

I' vo' bene a chi vol bene a me

(faixa 10) foi concebida instrumentalmente, com intermitentes

descolamentos da melodia original por uma das gaitas de foles. Em Per non far lieto alcun della mie doglia (faixa 11), foram compostas vozes de tenor e contratenor

para o canto, em defesa da possibilidade de improvisação de

acompanhamentos vocais ou instrumentais por parte de músicos que

dominassem as convenções polifônicas da época. Já em Donna, l'altrui mirar (faixa 12), o acompanhamento buscou essencialmente o uníssono das longas silabas vocalizadas.

O

manuscrito italiano de Londres (British Library) data de cerca de 1400 e

originou-se provavelmente na Ombria. Uma seção e fonte única de um

conjunto de composições instrumentais, incluindo oito stampitte, peças longas, com partes musicais (pars) finalizadas por um movimento cadencial suspensivo (aperto), seguido de repetição e conclusão (chiusso). Essas stampitte, incluindo a Isabella

(faixa 13) são formadas de motivos rítmico-melódicos explorados no

inicio das partes, com extensões irregulares, vindo de encontro à

hipótese de que esses trechos servissem de modelo para improvisações.

O Ultimo bloco e o mais pseudo-francês. Adiu, adiu, dous dame yolie (faixa 14), único e famoso virelai

de Landini, é notável pela concisão, generosa

expansão do canto e rica movimentação do contratenor.

Andrea

Stefani, florentino, foi professor elementar, copista e cantor.

Mostrou-se um compositor versátil nos poucos exemplos de sua autoria que

nos chegaram. Nino Pirrotta tem razão em identificar um intencional

gosto popular em seu madrigal I' senti' matutino, dado o flagrante contraste com a moderna e polirritmica ballata Con tutta gentilezza (faixa 15).

O

convento do Sancto Spiritu hospedou um francês, nascido em Narbona e

Mestre pela Universidade de Paris. A inscrição do cancioneiro autógrafo

do poeta Franco Sacchetti (c. 1365) "Mag. Guiglielmus Pariginus frater

romitanus" alude ao lugar de estudo e à ordem do religioso — romitanus =

eremitanus, ou seja, eremita, condição essencial dos agostinianos ate o

século XIII. Sacchetti colaborou com a letra de La neve, el ghiaccio (faixa 16). O canto do madrigal de Guiglielmus, finamente ornamentado e acompanhado por um tenor

transparente em sua condução melódica, é

incomum pela ausência de texto, sugerindo a opção

de ser tocado.

"Uma nova ordem, nova vida, surgiu no mundo, inaudita". O hino em

homenagem a São Francisco, atribuído a um de seus biógrafos, Tomás de

Celano, anuncia que a Igreja e a própria fé estavam em vias de serem

renovadas por Francisco de Assis, ao se exaltarem a caridade e a

pobreza. Em 1233 foi fundada a ordem dos Servos de Maria em Florença, na

esteira de muitas outras, chamadas mendicantes, incluindo a dos frades

menores franciscanos.

"Frate Andrea de' Servi" entrou para a ordem dos Servos de Maria em 1375. Foi prior da Casa da Santissima Annunziata,

onde supervisionou a construção de um órgão, contando com os conselhos

de Landini durante projeto e no momento de afinar o instrumento.

La divina giustizia

(faixa 17) e a composição menos "francesa" desta seção. Nela sobressaem

gestos dramáticos, com saltos melódicos e rápidas imitações livres,

próprios do estilo enérgico de Andrea. Inversamente, a ballade Dame sans per (faixa 18) é praticamente uma caricatura da mesura (contenance) francesa, do amor devotado e incondicional, cantado com economia de saltos e sem atribulações. Dame

é apenas atribuida a Andrea e figura no manuscrito de Módena

(Biblioteca Estense), cujos primeiros fascículos foram provavelmente

compilados entre 1410 e 1411, em Bolonha, durante a residência do papa

cismático na cidade.

Cantar à francesa, ou cantar Francescha à italiana? Seduzi-la de que maneira? Os versos da ballatina dançante de feições francesas — Amor mi fa cantar a la Francescha

(faixa 19) — não esboçam resposta, mas brincam com a dubiedade. O ritmo

é antes francês, mas os acentos são italianos. Deve-se enfim chorar por

Francescha, porque afinal ela é uma rosa (entre espinhos).

PEDRO H. NOVAES

SOBRE O ÓRGÃO PORTATIVO UTILIZADO

Uma

das vertentes da construção de órgãos na Idade Media seguiu o caminho

da miniaturização, chegando-se ao tipo portativo ou portátil em torno do

século XI. O órgão portativo e acionado por um único músico que, com a

mão direita toca um teclado e, com o braço esquerdo controla o

bombeamento e a pressão de ar através de um fole para fazer soar seus

tubos (flautas), sistema que possibilita alguma variação dinâmica. A

julgar pelas representações pictóricas e citações textuais dos séculos

XIV e XV teria estado muito em voga entre as elites culturais de cidades

norte-italianas da época, ainda assim não sobreviveu um único exemplar

ou, sequer, vestígios do instrumento. Celebres compositores toscanos,

como os amigos Francesco Landini e Andrea da Firenze — cujas composições

foram gravadas neste álbum — eram também organistas; Landini, cego,

ficou famoso em vida pelo domínio e capacidade de improvisação no

portativo.

A rica representação iconográfica relativa nos mostra

uma grande diversidade na sua estrutura de construção, indicando a sua

múltipla função na música polifónica

(ver vários exemplos em www.portativo.it).

Em sua versão mais comum era relativamente pequeno, leve e ágil,

próprio para a execução de versões ou variações instrumentais de vozes

superiores; mas poderia também comportar flautas maiores, sendo, neste

caso, destinado principalmente ao acompanhamento.

O portativo

utilizado pelo Conjunto Atempo, construido especialmente para este

programa por seu executante, comporta flautas de madeira, dispostas na

altura real e extensão das partes correspondentes ao tenor, linha

melódica de sustentação nas composições polifemicas medievais. O modelo

foi desenvolvido a partir da consideração de inúmeras fontes, tendo-se

em mente, sobretudo, a função que desempenharia no conjunto. As flautas

de bisel com canal longo, que dá grande estabilidade à coluna de ar, são

fechadas com embolo, condicionando a sua tessitura grave e afinação

precisa. Como na maioria das fontes iconográficas, as flautas estão

organizadas em duas fileiras paralelas sobre o someiro. O sistema de

aberturas das válvulas é do tipo direto (pin action),

controlado através de um teclado composto de botões cilíndricos de

madeira dispostos em dois níveis. O da frente compreende uma escala

diatônica de Dó2 a Lá3, e o de trás, mais elevado, comporta cinco dos

acidentes mais comumente encontrados no repertório musical da ars nova

italiana. A extensão do instrumento, primariamente condicionada ao

levantamento feito na música, é coincidentemente a mesma do manual do

órgão positivo de Norrlanda (Historiska Museet, Estocolmo), uma das únicas fontes vestigiais de órgãos do século XIV.

ALCIMAR DO LAGO

In 1301 Dante Alighieri lead a political delegation to Rome, with the

purpose of finding out the intentions of pope Bonifatius VIII's curia,

that was interfering in the political life of Tuscany. When still in

Rome, Dante was notified of his banishment from Florence; and a series

of events and further decisions would determine that never again would

he go back to his native city. Thus started Dante's pilgrimage through

Italian mansions and courts, while concentrating his energies in order

to compose the Comedy that Boccaccio, one of its earliest commentators, would call Divine.

During this period of Dante's life, one of the poet's favorite refuges

was the court of the Della Scala family, from Verona, that twice

received him as a guest (one of his patrons, Cangrande I, figures in his

opus magnum (Paradise, XVII, 76).

These episodes

of Dante's biography invite some reflections about art and patronage in

Florence and Verona along the fourteenth century.

In a similar way, this album is dedicated to the Trecento

polyphonic music of Florence and the Venetia - most likely from the

selfsame Veronese court of the Della Scala family, a few generations

after Dante's lifetime.

And how different were these two cities!

Florence did not have a central court: its powers were shared among its

prosperous tradesmen and the Church. Verona, more seignorial, for over a

century had been lorded by the Della Scala family.

Furthermore -

which is fortunate for us - the practice of polyphonic music in

Florence and Verona differed significantly. The Veneto, cradle of the

musical Ars Nova in Italy, would adopt the madrigal whose

musical notation and features were both original, while Tuscany, a few

decades later, would absorb many elements of the French aesthetics and

musical notation, choosing the ballata to be its main feature.

The

strengthening of cultural ties between Tuscany and France would partly

be a consequence of the regular commercial relations between Florentine

banks and French manufacturers of textiles. A good example of these

close relations is the conflict between Cardinal Piero Corsini and the

Florentine civil authorities, in 1378: as a consequence of it, the

cardinal and his retinue joined the French camp, moving to the papal

court in Avignon. This movement started as the college of cardinals,

under great pressure to put an end to the long exile of the pope in

Avignon (from 1309 to 1378) split and elected an Italian pontiff, Urban

VI. The French cardinals and their supporters summoned a parallel

conclave in which Clement VII was elected. Thus started the Great Schism

(1378-1417): a pope in Rome and another one in Avignon. Cardinal

Corsini was the scion of a conservative and influential family, and most

of his followers had bourgeois relatives considerably interested in the

French economy.

During the Trecento, the

Florentine intellectual and artistic life would thrive in a secular and

in a religious house, both somehow closely bound to France. The Alberti,

a dynasty of Florentine bankers, most influential in Europe, along the

second half of the fourteenth century, held business interests in Paris

and in Avignon. As for the Augustinian convent of Santo Spirito, whose

reputation steadily increased in the first half of the fourteenth

century, it lodged a free academy, active and independent from both

Church and University.

Most of the Florentine composers of the

fourteenth century were, somehow or other, associated with the Church.

Many were friars, chaplains or monks musicians. A few ones were just

organ players, but either as a consequence of their renown, of their

influence or by sheer chance, part of their works reached us, by being

recorded in codices. They worked in churches or monasteries. However,

the musical sources of the Ars Nova are, essentially,

compilations of profane music and its central theme is Love. If we take

into account the French influence on the Florentine society, it seems

only natural that its music should absorb France's aesthetic values. And

that's precisely what happened, starting from the coincidence of the ballata and the virelai or the chanson balladée (identical musical forms with a refrain). Circa 1370 the ballata

was the prevailing genre among the Florentine polyphonists. According

to Michael Long, in the second half of the fourteenth century, these

musicians saw themselves as the heirs of the French tradition in the

field of musical theory and preferred Philippe de Vitry to Marchettus of

Padua, who taught at the universities of Padua and Bologna and whose

system of musical notation would be widely adopted in Venetia but

prohibited in Florence.

The ballata Orne! s' io gli piango opens the album. It is attributed to Paolo da Firenze, also known as Dom Paolo tenorista, on account of his condition of monk (having even reached the rank of abbot) and of his skill as a composer. He was one of the uomini di stato

of Florence, that's to say, those citizens who occupied positions of

leadership in public life. In this capacity he was appointed to be an

ecclesiastical delegate at the Council of 1409, held in Pisa, a

neighboring city and historical rival of Florence. He left fifty

compositions, most of them ballate, whose styles go from traditional to avant-garde.

He was portrayed donning the black habit of the Benedictines, in the

most complete and luxurious musical manuscript of the Italian Ars Nova,

the Squarcialupi code, that, according to tradition, Paolo himself

helped to compile in the first years of the fifteenth century, shortly

before he died in his eighties. The staves for his compositions were

even traced on the pages of the code, but, for some reason, remained

empty; the manuscript 568, of the Italian fund, at the Bibliothèque

Nationale of Paris, a more modest one, is the only primary source of O me!.

"Villa Paradiso" was the title given to a proto-humanistic idyll by the chronicler Giovanni da Prato, in Il Paradiso degli Alberti (1389). In this romanza, characters more real than fictional - in contrast to Boccaccio's Decameron

- participate of daily events in the Alberti gardens. One passage is

noteworthy: "[...] for everybody's delight and especially Francesco's,

two damsels sang and danced his Orsun gentili spiriti with

such sweetness, that not only the audience was affected by it, but even

the birds, on the cypress trees, started singing more sweetly." The

Francesco in question is Landini, born in Fiesole, in the vicinity of

Florence. Being the son of a painter of Giotto's school, he received a

liberal education, learned how to cope with the blindness that affected

him in childhood and acquired a renown as an organist, poet and

composer. Il divino, a rare epithet, was bestowed on

Dante, Michelangelo and also on Landini, and shows to which extent went

the recognition of his art by the Italians.

The bands 2 to 5 are a set of Landini's ballate for two or three voices. The first one, is an instrumental version of I' fu tuo servo, amore and is played in the manner of a prelude to the whole group. Lasso! di donna, Ognor mi trovo e Po' che partir convien

closely follow certain conventions of courtly love poetry, which is

more vocative than narrative, more confessional and denotative of one's

feelings. Lasso! di donna describes the pangs of an

inexorable love for a cruel woman. It is well known that a few centuries

earlier the troubadours were entitled to go against common sense by

addressing to their beloved poems full of suspicions. The same custom

still prevailed in later centuries, in the meridional lands of Europe,

such as Italy, and this will be illustrated by other ballate of our program.

Between

the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth century, any Italian

desirous of expatiating about the vagaries of love, praising his

patrons (not mattering whether these were great lords or petty tyrants),

attacking his own enemies or uttering moralizing sentences, would be

advised to pick out the madrigal as his form of expression. In the

madrigal, the discourse was woven on an allegorical, subtextual

narrative, which offered the advantage of safeguarding its author.

Also

in the artistic duels - an attraction in the Italian courts of the

fourteenth century - the madrigal used to be a frequent device. At one

stroke the opponents would reveal their qualities as poets, composers,

singers or instrumentalists. It is well known that Jacopo da Bologna,

Giovanni da Cascia and Maestro Piero, all at the service of Northern

courts, as well as Francesco Landini, taught by Jacopo, confronted each

other on several occasions. The chronicler Filippo Villani narrates a

contest that took place in Venice, in 1364. Among the jurors was the

elderly Petrarch. At the end of it Landini would receive the laurels

from the hands of Peter the Great, king of Cyprus, but Francesco Pesaro,

of San Marco, would be considered the best organist of the contest, in

spite of Landini's obvious virtuosity. Be that as it may, the feat of

the 'organist from Florence' would not sink into oblivion: in an

illuminated page of the codex Squacialupi, Landini is portrayed wearing

his laurels. In a word, the custom of putting to test one's abilities at

improvisation, poetry and musical virtuosity revealed a competitive

environment. According to Nino Pirrota, to magnify one's merits and

disdain those of one's rivals was a part of the whole game. We don't

know to whom were addressed the lines of the madrigal I'me son un che per le frasche andando, by Jacopo da Bologna; but here is the irony of its final distich: "corvo che di paon veste la penna / fra'papagal in vergogna si spenna" [a raven that wears a peacock's feathers / has its feathers shamefully plucked among the parrots].

Compositions from Venetia, probably written in Verona, at the court of

the Della Scala family, reached us in the Vatican codex Rossi 215. These

are the first known madrigals and, most of them, are vocal duets. Love

and Nature are allegorically associated in them. In the madrigal Chiamando un'astorella

(band nine of this album), Love is chased "through woods and meadows,

roads and havens" and flees in the guise of a bird. In these

compositions hunt, fires, storms, as well as the onomatopoeias required

by the narrative, are pretty familiar events, but the Northern Italian

madrigals and ballate (including those from the codex

Rossi) have as a characteristic feature a rhapsodic style, as Pirrotta

calls it. Some elements of such style, noticeable in the relation

between music and text, would hardly go unobserved.

Compositions from Venetia, probably written in Verona, at the court of

the Della Scala family, reached us in the Vatican codex Rossi 215. These

are the first known madrigals and, most of them, are vocal duets. Love

and Nature are allegorically associated in them. In the madrigal Chiamando un'astorella

(band nine of this album), Love is chased "through woods and meadows,

roads and havens" and flees in the guise of a bird. In these

compositions hunt, fires, storms, as well as the onomatopoeias required

by the narrative, are pretty familiar events, but the Northern Italian

madrigals and ballate (including those from the codex

Rossi) have as a characteristic feature a rhapsodic style, as Pirrotta

calls it. Some elements of such style, noticeable in the relation

between music and text, would hardly go unobserved.

Three madrigals and a rondello — a rare and old fashioned genre in the Trecento

— are part of a Northern Italian section (bands six to nine). Among

the pieces we chose it is a common procedure that the recitation of the

text be rhythmically stressed between the first, very ornated voice —

the superius —, and the second one — the tenor

— ready to sacrifice a virtual polyphonic independence for the sake of a

dramatic musical impact, not unlike an improvisation. This perception

is emphasized by the fortuitous sequences of parallel musical intervals.

As an example of the frequent occurrence of melodically augmented

intervals, one can point to a passage of the madrigal Chiamando un'astorella, in which the cadential ascending movement of the tenor coincides with the word vola [it flies about] in the line "Nelcor doneça e per la gabia vola"

[She dominates with her heart and flies about in the cage.] Also

frequent are the rhetorical devices of reiteration and interpolation.

The more acute and final section of Sovra un flume regale, a madrigal by Maestro Piero (band 8, in instrumental version) is an example of that: "Anna, mio cor, Anna, la vita mia". For similar reasons, Nino Pirrotta recalls the lines of an anonymous ballata, Occhi pianpete: "[...] (et) con dolorose pene / da la donna reale esser privato (oimè privato)"

The tales of Boccaccio's Decameron

(c. 1350) contain numerous references to music and dance. These stories

are linked by temporal and spatial proximity to the first signs of the

flourishing of the Ars Nova in Tuscany. They describe an

ambiance both erotic and libertine, in the hills of Fiesole, next to

Florence, where ten young aristocrats seek refuge from the Black Death

(1348-1350) that devastates all the Western World. There, Dioneo plays

the lute and Fiametta the vielle, in the beginning of the first giornata; Tindaro's bagpipe sounds at the end of the seventh.

In Florence, overcoming the epidemics, Gherardello was chaplain of the former cathedral of Santa Maria Reparata. His ballate

are the closest ones to their popular origin. They are all monophonic —

with one melodic line original — and carefully ornate. Another composer

from the same generation, Lorenzo Masini, set to music a poem by

Boccaccio, in the ballata Non so qual i' mi voglia.

I' vo' bene a chi vol bene a me

(band 10) which originally was a vocal piece, will be heard here

thoroughly instrumental, with intermittent wanderings from the original

melody by one of the bagpipes. In Per non far lieto alcun della mie doglia

(band 11) the voices of tenor and counter-tenor were written down, as a

defense of the possibility of being improvised a vocal or instrumental

accompaniment by musicians who master the polyphonic conventions of that

epoch. On the other hand, in Donna, l'altrui mirar (band 12) the accompaniment basically sought the unison of the long vocalized syllables.

The Italian manuscript from London (British Library) dates back to

c. 1400 and most likely originated in Umbria. One section of it is the

single source of a set of instrumental compositions that includes eight stampitte, long pieces with musical parts ending in a suspensive cadential movement (aperto), followed by repetition and conclusion (chiusso). Those stampitte, including Isabella

(band 13), are formed by rhythmic-melodic motives exploited in the

beginning of the parts, of irregular extensions, which seems to uphold

the hypothesis that such passages were models for improvisation.

The last set is the most pseudo-French of all. Adiu, adiu, dous dame yolie (band 11), the famous single virelai

composed by Landini, is remarkable for its concision, generous

expansion of the singing voice and rich movements of the counter-tenor.

Andrea

Stefani, Florentine, was an elementary school teacher, a copyist and a

singer. He proved to be a versatile composer in the few of his pieces

that survived. Nino Pirrotta is right when he identifies an

intentionally popular character in his madrigal I' senti' matutino, if one compares it to the modern and polyrhythmic ballata Con tutta gentilezza (band 15).

The

convent of Santo Spirito received as a guest a Frenchman born in

Narbona, with a Master of Arts degree from the University of Paris. The

reference left in the autograph of the canzoniere by the

poet Franco Sacchetti is "Mag[ister] Guiglielmus Pariginus frater

romitanus", with an allusion to the place where he studied and to the

religious order of which he was a member (romitanus is bad Latin for eremitanus,

that is to say, a hermit - an essential condition of the Augustinians,

until the thirteenth century). Sacchetti wrote the lyrics for La neve, el ghiaccio.

The vocal part of Guigliemus, delicately ornated and accompanied by a

transparent tenor in its melodic conduction, is unusual in that it has

no text, as if suggesting the possibility of being performed by

instruments.

"A new order, a new life appeared in the world,

something unheard of". The hymn in homage to Saint Francis, attributed

to one of his early biographers, Thomas from Celano, announces that the

Church and faith itself were about to be renovated by Francis Assisi, as

he exalted charity and poverty. In 1233 the order of the Servants of

Mary was founded in Florence, in the wake of many others, called

mendicant orders, such as the order of the Franciscan Minors.

"Frate

Andrea de' Servi" entered the order of the Servants of Mary in 1375. He

became the prior of the convent of the Santissima Annunziata, where he

supervised the construction of an organ, relying on Landini's advice,

all along the execution of the project and also at the moment of tuning

the new instrument.

La divina giustizia (band 17)

is the least "French" composition of this section. Its main features are

dramatic gestures, with melodic leaps and the quick free imitations,

characteristic of Andrea's energetic style. Reversely, the ballade Dame sans per

(band 18) is practically a caricature of French composure, of the

devoted and unconditional love, sung with economy of leaps and without

any tribulations. Dame is attributed to Andrea and is

included in the Modena manuscript (Biblioteca Estense), whose first

fascicles were probably compiled between 1410 and 1411, in Bologna, when

the schismatic pope sojourned in town.

To sing after the fashion

of the French, or to sing Francescha after the Italian fashion? How to

entice her? The lines of the dancing ballatina with French features - Amor mi fa cantar a la FRANCESCHA

(band 19) - don't suggest any answer, they rather play with ambiguity.

The rhythm is certainly French, but the accent is Italian. After all,

one should cry for Francescha, because she is a rose (among thorns).

PEDRO H. NOVAES (English version by Sergio Pachá)

ABOUT THE PORTATIVE ORGAN EMPLOYED

One of the roads taken

by the fabrication of organs in the Middle Ages was that of

miniaturization, which led to the portative type of organ, around the

eleventh century. The instrument is played by a single musician, who

uses his right hand to press a keyboard, and the left one to control the

pumping and pressure of the air by means of bellows, in order to sound

its pipes (flutes), a system that allows some dynamic variation. The

pictorial representations and the testimony of texts from the fourteenth

and fifteenth centuries induce us to believe that it used to be all the

rage among the cultured upper class of the northern Italian cities at

that time; and yet not one single portative organ, or even parts of it,

survived. Several famous Tuscan composers, such as the friends Francesco

Landini and Andrea da Firenze — of whom some compositions were recorded

in this album — were also organists, and Landini, who was blind, was

celebrated during his lifetime for his mastery and skill to improvise on

the portative organ.

The rich existent iconography of portative

organs shows a great diversity in their structure, which points to their

multiple functions in polyphonic music (there are several examples of

this at www.portativo.it).

Its prevalent model was pretty light and easy to handle, and thoroughly

adequate to the performance of instrumental versions of superior

voices, or variations; sometimes, however, it was endowed with bigger

flutes and was mostly employed as an accompanying instrument.

The

portative organ used by the ensemble Atempo was built for this program

by its performer. Its flutes are made of wood and have the same range as

the tenor voice, whose function in the early polyphonic music was

holding (tenere in Latin) the melodic line. The

development of its model was based on several different sources, with a

view to the function to be fulfilled by the instrument in the ensemble.

The long fipple flutes, closed by plungers, provide a great stability to

the air column. Their tessitura is low and their pitch is precise. As

in most of the iconographic sources, the flutes are disposed in two rows

on the soundboard. The system of openings of the valves is the pin

action kind, controlled through a keyboard made of cylindric wooden

buttons disposed on two levels. The front level comprehends a diatonic

scale from C2 to A3; the rear level, in a higher position, corresponds

to the five more frequent accidentals to be found in the repertory of

the Italian Ars Nova. The range of the instrument,

directly based on the study of the music it is designed to play,

coincidentally is the same as the one of the manual keyboard of the

positive of Norrland (Historiska Museet, in Stockholm), one of the few vestigial sources of fourteenth century organs.

ALCIMAR DO LAGO (English version by Sergio Pachá)

As faixas 2 a 5 encerram uma seção de ballate de Landini, escritas a duas ou três vozes. Inicia-se com I' fu tuo servo, em versão instrumental, servindo de prelúdio para o bloco. Lasso! di donna, Ognor mi trovo e Po' che partir convien

seguem de perto certas convenções da poesia do amor cortés, mais

vocativa do que narrativa, confessional e reveladora dos estados da

alma. Lasso! di donna descreve a angústia de um amor

inexorável por uma mulher cruel. Contrariando o senso comum, sabe-se que

os trovadores, séculos antes, tinham todo o direito de endereçar versos

desconfiados às amadas, direito esse amplamente exercido em terras

meridionais e na Peninsula Itálica, a exemplo de outras ballate do nosso programa.

As faixas 2 a 5 encerram uma seção de ballate de Landini, escritas a duas ou três vozes. Inicia-se com I' fu tuo servo, em versão instrumental, servindo de prelúdio para o bloco. Lasso! di donna, Ognor mi trovo e Po' che partir convien

seguem de perto certas convenções da poesia do amor cortés, mais

vocativa do que narrativa, confessional e reveladora dos estados da

alma. Lasso! di donna descreve a angústia de um amor

inexorável por uma mulher cruel. Contrariando o senso comum, sabe-se que

os trovadores, séculos antes, tinham todo o direito de endereçar versos

desconfiados às amadas, direito esse amplamente exercido em terras

meridionais e na Peninsula Itálica, a exemplo de outras ballate do nosso programa.

Compositions from Venetia, probably written in Verona, at the court of

the Della Scala family, reached us in the Vatican codex Rossi 215. These

are the first known madrigals and, most of them, are vocal duets. Love

and Nature are allegorically associated in them. In the madrigal Chiamando un'astorella

(band nine of this album), Love is chased "through woods and meadows,

roads and havens" and flees in the guise of a bird. In these

compositions hunt, fires, storms, as well as the onomatopoeias required

by the narrative, are pretty familiar events, but the Northern Italian

madrigals and ballate (including those from the codex

Rossi) have as a characteristic feature a rhapsodic style, as Pirrotta

calls it. Some elements of such style, noticeable in the relation

between music and text, would hardly go unobserved.

Compositions from Venetia, probably written in Verona, at the court of

the Della Scala family, reached us in the Vatican codex Rossi 215. These

are the first known madrigals and, most of them, are vocal duets. Love

and Nature are allegorically associated in them. In the madrigal Chiamando un'astorella

(band nine of this album), Love is chased "through woods and meadows,

roads and havens" and flees in the guise of a bird. In these

compositions hunt, fires, storms, as well as the onomatopoeias required

by the narrative, are pretty familiar events, but the Northern Italian

madrigals and ballate (including those from the codex

Rossi) have as a characteristic feature a rhapsodic style, as Pirrotta

calls it. Some elements of such style, noticeable in the relation

between music and text, would hardly go unobserved.