Madame d'amours. Music for Renaissance Flute Consort

The Attaignant Consort

medieval.org

Ramée RAM 0706

2007

1. Madame d'amours [1:32]

consort à 4

2. The Duke of Sommersettes Dompe [2:03]

lute solo

3. Robert FAYRFAX (1464—1521). Farewell my joy

[2:09]

flute and lute

4. My Lady Careys Dompe [1:58]

harp solo

5. Henry VIII (1491—1547). Pastyme with good companye

[1:50]

consort à 4, lute and harp

—·—

JOSQUIN (1440—1521)

6. In pace ~ Que vous madame [4:17]

consort à 3

7. Mille regretz [1:37]

consort à 4 and harp

8. Luys de NARVÁEZ (?—1549). La Canción del

Emperador (Mille regretz) [2:35]

lute solo

Heinrich ISAAC (c. 1440—1517)

9. Güretzsch ~ Si dormiero [3:45]

consort à 3

10. La my [2:21]

consort à 4

—·—

11. Arnolt SCHLICK (c. 1460— after 1521). Mein M. ich hab

[1:49]

flute and lute

12. Paul HOFHAIMER (1459—1537). Ach Lieb mit Leid

[1:35]

consort à 4

13. Ludwig SENFL (1486—1542). Carmen [0:52]

consort à 4

14. Hans JUDENKÜNIG (c. 1460—1526). Ein seer guter

Organistischer Preambel [3:05]

lute solo

15. Georg FORSTER (1510—1588). Ich habs gewagt

[1:20]

consort à 4

16. Das Jägerhorn [0:54]

consort à 3

—·—

17. Jacob OBRECHT (1456—1505). Qui cum Patre et Filio

[1:54]

2 bass flutes

18. Orlando di LASSO (1530—1594). Beatus Vir [1:14]

2 tenor flutes

19. Tomás Luis de VICTORIA (1548—1611). Tenebrae

factae sunt [4:19]

consort à 4 – 2 tenor and 2 bass flutes, harp and lute

—·—

Claudin de SERMISY (1490—1562)

20. Tant que vivray [1:51]

consort à 4 and harp

21. Au pres de vous [2:24]

consort à 4

22. Nicolas GOMBERT (1495—1560). Amours,amours

[2:03]

consort à 4

23. Pierre SANDRIN (1538—1560). Doulce memoire

[3:43]

consort à 4, harp and lute — divisions by Diego ORTIZ

(1510—1570)

24. Jean-Paul PALADIN (?— 1565). Le content est riche

[2:20]

harp solo

25. Jacobus CLEMENS non Papa (1510—1555). Frais et Gaillard

[3:31]

flute and harp — divisions by Giovanni BASSANO

(1560—1617)

26. Claudin de SERMISY. Au joly bois [3:22]

consort à 4 – 2 tenor and 2 bass flutes, harp and lute

27. Clément JANEQUIN (1485—1558). Le rossignol. En

escoutant [1:45]

consort à 4

—·—

28. Alfonso FERRABOSCO (1543—1588). Fantasia [3:25]

lute solo

29. Cipriano de RORE (1515—1565). Anchor che col partire

[3:57]

flute and lute — divisions by Riccardo ROGNONI (c.

1550—1620)

30. Ricercada [1:55]

harp solo

—·—

John DOWLAND (1563—1626)

31. Pavan Lachrimae [4:37]

flute and lute — divisions by Jacob van EYCK (c.

1589—1657)

32. Praise blindnesse eies [2:16]

consort à 4 and lute

33. Fine knacks for ladies [1:42]

consort à 4 and lute

THE ATTAIGNANT CONSORT

KATE CLARK direction, flute

FRÉDÉRIQUE CHAUVET flute

MARION MOONEN flute

MARCELLO GATTI flute

THE ATTAIGNANT CONSORT

gratefully acknowledges the magnificent

collaboration, for this recording, of

MATHIEU LANGLOIS flute

MARTA GRAZIOLINO harp

NIGEL NORTH lute

CONSORT À 4:

Kate Clark, descant—Frédérique Chauvet,

alto—Marion Moonen, tenor—Marcello Gatti, bass

(except for 19 and 26:

Kate Clark, tenor—Marion Moonen, tenor—Mathieu Langlois,

bass—Marcello Gatti, bass)

CONSORT À 3:

Kate Clark, descant—Marion Moonen, tenor—Marcello Gatti,

bass

BASS FLUTES IN 17: Marcello Gatti, Mathieu Langlois

TENOR FLUTES IN 18: Kate Clark, Marcello Gatti

All flutes: Giovanni Tardino, Rome 2000, after anonymous 16th-century

builder (collection in the Academica

Filarmonica, Verona)

Arpa doppia, Enzo Laurenti, Bologna 1999, after 17th-century Italian

instrument

Eight-course renaissance lute, Paul Thomson, Bristol 1999, after

Vendelio Venere, c. 1580

Recorded in May 2007 at the church of Notre-Dame de l'Assomption,

Basse-Bodeux, Belgium

Recording, artistic direction, editing & production: Rainer Arndt

Graphic concept: Laurence Drevard

Design & layout: Rainer Arndt, Catherine Meeùs

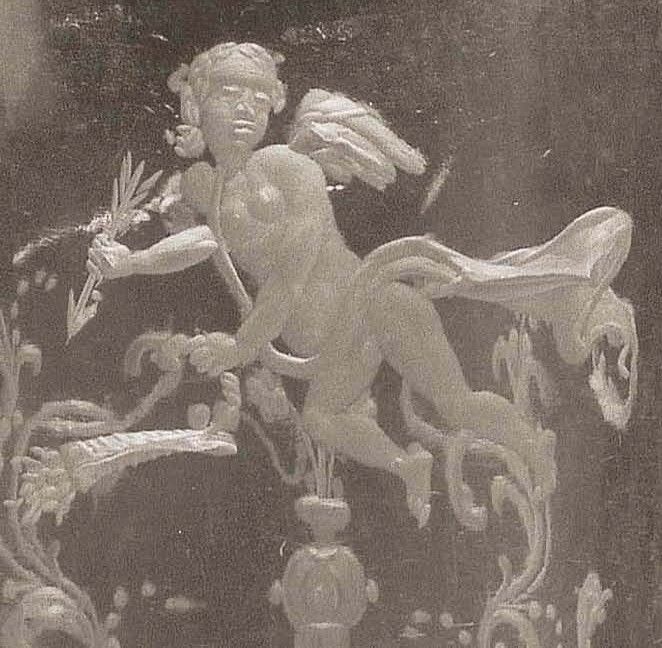

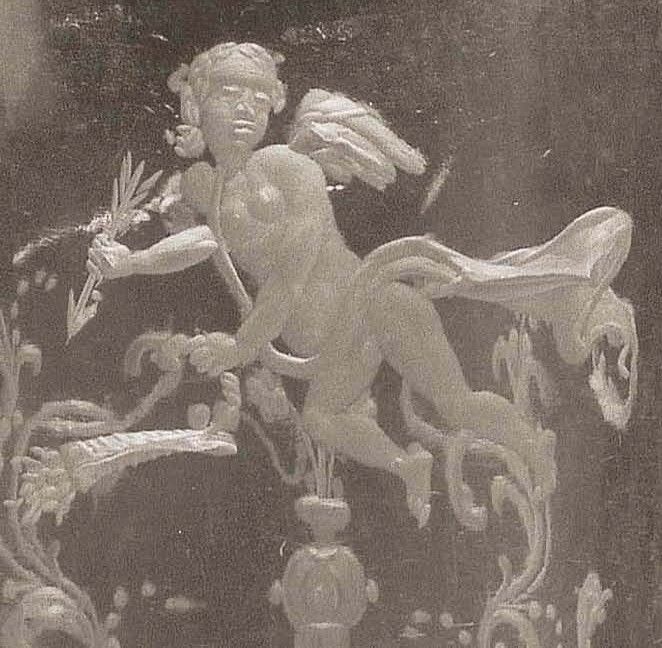

Cover: Flagon ornamented with a winged Cupid and motives

»à la Bérain«,

France, 17th century

Photos: © bpk/RMN/Musée du Louvre/Jean-Gilles Berizzi

(cover)

© Laura Lombardi (booklet)

Translations: Rainer Arndt (German)

Frédérique Chauvet, Catherine Meeùs (French)

MUSIC FOR RENAISSANCE FLUTE CONSORT

From the early renaissance to the present day, the slender, side-blown

flute of the Western art music tradition has undergone a series of

transformations. Its interior contour has changed from being

cylindrical to being conical and back again, it has gained and lost

various keys, and the mechanisms for operating them have been

successively refined. While woods of various kinds and colours have for

centuries been most favoured for its construction, the flute was also

given form in glass, crystal and ivory, surviving in the mid-nineteenth

century a truly remarkable transformation into a shimmering pipe of

precious metal. Today, an enduring preference for the sound of wooden

flutes is reasserting itself, as many players of the

»modern« flute redesigned by Theobald Böhm are turning

again to wooden-bodied flutes, silver being reserved for the slide and

key mechanisms only.

The flute of each period had its own distinctive sound, peculiar to the

musical epoch in which it flourished. The elegant, keyless, cylindrical

flute of the sixteenth century had a reedy, penetrating sound, closer

to the cornetto than to any other wind instrument of the day. It had an

impressive range of two and a half octaves and an evenness of tone

quality that would not be matched again until the nineteenth century.

Its dynamic flexibility and responsiveness to subtleties of

articulation endowed it with a vocal quality. And, for all its outward

simplicity, it was capable of a startling virtuosity. Together with its

bass and descant variants, it played a full part in that distinctive

sixteenth-century musical phenomenon: the instrumental consort.

In this recording we focus on repertoire for the renaissance flute

consort, almost all of which was originally vocal music. We have

included a number of purely instrumental pieces, Heinrich Isaac's La

my, Ludwig Senfl's Carmen, and the Anonymous Jägerhorn

which show the agility of which the consort was capable. There are

several pieces for one flute with lute or harp in which the flute's

role is closer to that of the singer-poet or narrator, conveying the

words of a song in a polyphonic context in which the other voices are

carried by the plucked instrument as in Robert Fayrfax's Farewell

my joy and Arnolt Schlick's Mein M. ich hab.

Some of the solo pieces are presented in highly ornamented versions,

known as »divisions« in which little melodic flourishes,

each with a rhythmic life of its own, have replaced (or

»divided« up) the longer notes of the original. Divisions

gave new life, perhaps a contemporary flavour, to popular melodies from

previous generations. Riccardo Rognoni's divisions on Cipriano de

Rore's Anchor che col partire, and Jacob Van Eyck's on John

Dowland's Pavan Lachrimae are two famous and beautiful examples.

Other pieces present diminutions in several parts simultaneously within

the consort context. This practice, well documented in

sixteenth-century sources, called for extra skill, generally requiring

that the diminutions be written down for each part rather than

improvised in performance, so as to avoid undesirable clashes or

dissonances between parts (though surprising dissonances are not

entirely absent from some of the most beautiful composed divisions of

the period). Diego Ortiz's version of Pierre Sandrin's Doulce

memoire provides diminutions for both descant and bass voices

simultaneously. For Claudin de Sermisy's Au joly bois I have

composed divisions for all four voices. Other incidental divisions in

the recording have been improvised in the performance.

Finally we present a number of pieces for lute and harp solo, the two

»classic« polyphonic instruments of the renaissance world

of bas or soft instruments. The association of flute with

plucked instruments may be traced far back in the history of both

Western and Eastern musical traditions. The juxtaposition of the

melancholy lyricism of the one with the quietly stunning articulacy and

eloquence of the others, has captivated musicians and listeners for

centuries.

THE AGE OF THE FLUTE CONSORT

By the year 1600, hardly a musician alive could remember when the

practice of playing in consorts had begun. The word had come to denote

a group of musicians playing upon a family of like instruments

– or the family of instruments itself – made in several

different sizes so as to reproduce the registers of the ensemble of

human voices: bass, tenor, alto and descant. It was no less than the

instrumental embodiment of the vocal ensemble. By then a

long-established feature of the musical landscape in English, German,

French and Italian-speaking lands, it was destined to persist well into

the seventeenth century, and to have consequences for musical practice

far further into the future.

Yet the very idea of such a consort once swept across Europe like a

scented breeze intimating the coming of spring. It brought the promise

of new possibilities of expression and participation in music making.

The ascendancy of the consort principle went hand in hand with the

spread of polyphonic music from the sacred into the secular realm, and

the consort was uniquely placed to exploit the rise of imitative

counterpoint as the dominant compositional model, in which all voices

played an equally important role. Indeed, it is hard not to see in the

consort principle, with all its various implications for communal

music-making, both a product and an instrument of humanist influence.

In the eyes of humanists, human endeavour attained a new, enhanced

status. In music, secular forms moved into a new relationship with

sacred ones to which they had formally been considered subordinate. A

basic education in music and private music making for devotional or

recreational purposes were considered to be good for individual

morality. At the same time, the growing market of players wishing to

play in consort in the early sixteenth century was both beneficiary and

patron of a revolutionary new industry: music-printing.

The transverse flute was not among the first instruments to be adapted

for consort use. However, within the first three decades of the

sixteenth century the practice of playing transverse flutes in consort

had taken hold in Western Europe. A comparison of the earliest treatise

documenting the existence of the transverse flute (Sebastian Virdung,

Musica Getutscht, 1511) with treatises by later sixteenth-century

authors helps to locate the emergence of the transverse flute consort,

in German-speaking areas at least, somewhere between 1511 and 1529.

Virdung's little page illustrating mouth-blown wind instruments

presents two sizes of shawm (the longer is called a Bombardt),

and three sizes of recorder, but shows only one Zwerchpfeiff or

transverse flute. In 1529, by contrast, Martin Agricola's Musica

Instrumentalis Deudsch, presented drawings and fingering charts for

a whole consort of flutes. His charts clearly refer to three sizes of

flute only, and make clear too that the tenor and alto parts were

played upon one single size of flute, the lower part of its range being

used for the tenor part and the upper part for the alto. This accords

with all the other sixteenth-century documents on the use of transverse

flutes. Later in our period, the descant flute appears less often: the

middle length flute (fundamental d') having the largest range and

greatest flexibility, had subsumed the role of the descant, and later

consorts comprised one bass and three »tenors«. Indeed it

was the tenor flute which survived mutation into the solo flute of the

baroque and later periods. During the late eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries it acquired longer foot joints extending its range downward

to c' and even b. In its latest incarnation as an instrument made from

metal (c. 1847) this aspect of its historical construction was not

altered.

In England the flute consort was identified for the first time in a

document dated 10th December 1543, though the names of two of the

flautists mentioned in that document first appear in court records in

1537. In his sleuthful sifting through sixteenth-century English court

records on the trail of the history of the violin, Peter Holman exposed

a picturesque metamorphosis: »It seems that the court rebec

consort was replaced (or was changed into) a flute consort in the

1540s«. Players of soft or indoor instruments were generally

skilled on several different ones. As the rebec became outmoded, those

players assigned to perform on it were given other functions more in

keeping with current musical taste. Certainly, by the death of Henry

VIII in 1547, a vast inventory of flutes had been acquired.

In France we have a delightful moment of illumination in 1533 with

Pierre Attaignant's publication of Vingt et sept chansons musicales

a quatre parties desquelles les plus convenables a la fleuste dallemant

sont signees en la table cy dessoubz escripte par a. et la fleuste a

neuf trous par b. et pour les deux par a b. [...] (Twenty-seven

chansons for four parts, of which those most suitable for playing on

the german flute are marked in the index by the letter 'a', those for

the recorder with the letter 'b' and those suitable for both with the

letters 'ab' [...] – The transverse flute had come to be known

across Europe variously as the »german flute«,

»fleuste d'allemand« or »flauto tedesco«

because of its association with military practice particularly by the

Swiss, but also among other German speaking soldiery). Obviously,

Attaignant's publication was aimed at players participating in an

already existing practice.

THE REPERTOIRE

There are two other developments in mid-renaissance Europe that fuelled

the veritable explosion of interest in playing upon consorts of

instruments: the craze for the French (language) chanson which spread

far beyond the borders of French-speaking Europe, and the invention of

music printing, which made polyphonic repertoire, from Josquin's

generation to the sixteenth-century present, available on a scale never

seen before.

Among the most-favoured secular genres in the sixteenth century, the

chanson occupies a distinguished place by virtue of its enormous and

international popularity, and its profuse representation in manuscript

and early printed collections of instrumental music. Chanson here

refers specifically to polyphonic settings of French verse. These were

set by composers from within and without the French kingdom, notably by

many composers from the Low Countries (and consequently known as

»Franco-Flemish chansons«). It is not surprising then, that

when Ottaviano Petrucci came to produce the first book of printed

polyphonic music, his Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A (Venice,

1501), he devoted it almost entirely to the French chanson. Evidently

he considered this the safest basis from which to proceed on what was

plainly an entrepreneurial adventure: he had invented a technique for

printing music from moveable type, and his work was to change the music

industry for ever. Two further books of chansons followed promptly: Canti

B (1501/2) and Canti C (1503/4), confirming his business

acumen as to the popularity of this particular repertoire.

While Attaignant, aiming at a French-speaking market, printed his part

books with texts, albeit often poorly underlayed, Petrucci printed his

chansons, with very few exceptions, with text incipits only. The most

plausible explanation (though it has not been an uncontested one) for

the wide-spread transmission of secular polyphony in textless versions,

from the second half of the fifteenth century onwards, is that it was

increasingly often played and enjoyed in instrumental versions.

For The Attaignant Consort, the chanson repertoire has been an

immensely fruitful and delightful point of departure, and source of

inspiration, since its inception in 1998. We have constantly returned

to it, after each sortie into other genres and national styles. That

fleeting moment of illumination provided by Attaignant's introduction

to his Vingt et sept chansons, is no more than a momentary

flicker of candle-light in the dimness that still shrouds our present

knowledge of renaissance instrumental performance practice. Yet I am

quite unable to believe that the connection he pointed to between

French chansonnerie and performance by transverse flute consort

reflected only a haphazard circumstance of his immediate surroundings.

For in this repertoire, the renaissance flute seems to encounter no

obstacles whatever in expressing everything the music calls for: the

ranges of the parts, the tonalities in which chansons were most

commonly written, the sentiments expressed in their poetry, and even

the French language itself, seem perfectly suited to this instrument's

natural capacities.

Certainly, for this sixteenth-century chronicler, there was a marriage

– so to speak – between the transverse flute and the French

which simply spoke for itself: »[...] il y avoit une

fleute-traverse, que l'on appelle à grand tort fleuste

d'allemand; car les Français s'en aydent mieulx et plus

musicalement que tout aultre nation; et jamais en Allemaigne n'en fust

joué à quatre parties, comme il se faict ordinairement en

France.« (»there was [playing on] a transverse flute,

which is called, quite erroneously, the German flute; because

the French play it better and more musically than any other nation; and

never in Germany was it played in four parts as it commonly is in

France.«)

There is evidence to suggest that professional musicians aimed to

conjure up in their playing not only the sentiments of the text, but

the inflections of the voice and even the pronunciation of the words as

it would be present in a vocal performance; this was the ideal for

which they strove. Sixteenth-century writers on flute playing give only

scanty indications as to how such an ideal might be attained in

playing, but their comments on how to »lead« each note with

the tongue, or how to nuance expression through a variety of

»double« tonguing techniques are telling enough to the

experienced player. With regard to the ultimate aesthetic goal of such

mastery, it has been illuminated for us by a most articulate

contemporary witness: Silvestro Ganassi, who concludes the introduction

to his famous treatise La Fontegara (1535) as follows:

»You may ask me: How is that possible, [the voice] being

something that can utter every [kind of] speech such that I do not

believe that the flute can ever equal it? And I answer you, that just

as a worthy and masterly painter imitates all things created in nature

by [means of] the variation of colours, so can a wind or string

instrument imitate the utterances made by the human voice; [...] And if

the painter imitates the impressions of nature by means of varied

colours, so the [wind] instrument imitates the expressions of the human

voice by modulation of the force of the breath, and by inflection of

the tongue [offuscation della lingua], with the help of the

teeth [deti*]. And in this respect I have had the experience of

hearing other players render understandable with their sound, the words

of that piece [they are playing], such that one can truly say that this

instrument lacks nothing but the form of the human body itself, just as

one says of a beautiful painting that all it lacks is breath.«

(*There is disagreement among scholars as to whether the teeth or the

fingers are intended by the word deti.)

The poetry of all vocal pieces recorded here is included in the back of

the book so as to put the listener in the position of a

sixteenth-century connaisseur who may glean the spirit, the

gesture, and even the intimate details of the text from the

instrumental performance.

This recording is dedicated with gratitude to Norma Scott and Anne

Smith for their guidance at the two most hazardous moments in my own

formal education as a flautist – the beginning and the end.

Kate Clark