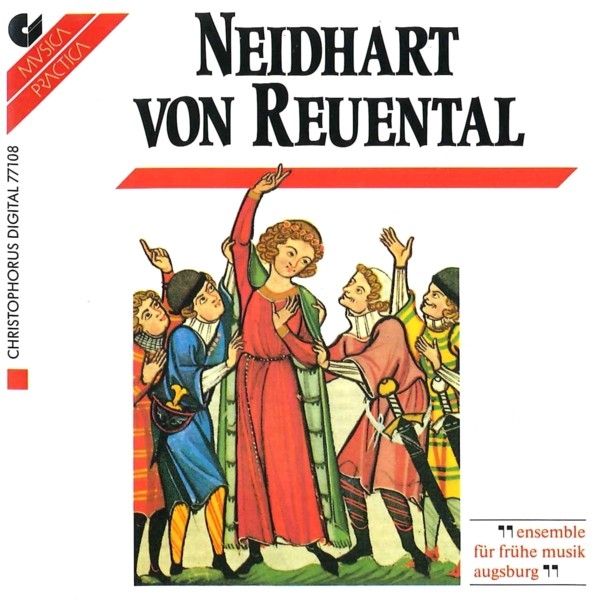

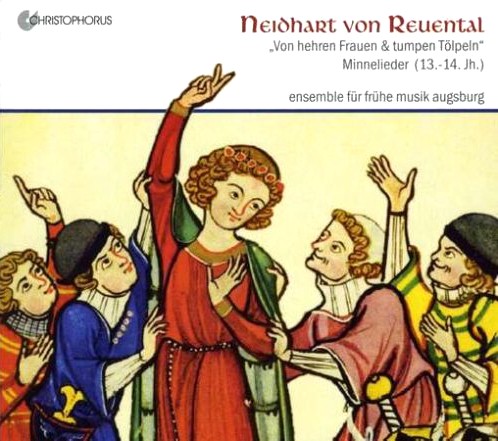

Neidhart von REUENTAL

Ensemble für frühe Musik, Augsburg

medieval.org

Christophorus CD 77108

1990

reedición 2010: Christophorus CHR 77327

01 - Sing ein guldein hun [2:44]

Sänger 1, Blockflöte, Fidel, Chitarra sarazenica, Schlagwerk

02 - Mir ist von herczen laide [5:16]

Sänger 1/2, Fidel, Harfe

03 - Ich gesach die heide nye so gestalt [3:34]

Sängerin, Blockflöte, Lira, Mittelalter-Laute

04 - Mayenzeit one neidt [5:11]

Sänger 1, Blockflöte, Schalmei, Fidel, Mittelalter-Laute, Schlagwerk

05 - Mann hort nicht mehr süssen schal [3:22]

Sängerin, Sänger 1

06 - Do der liebe summer [5:51]

Sänger 2, Blockflöte, Fidel, Chitarra sarazenica

07 - Maye dein wunnewerde zeit [4:47]

Sänger 1/2, Schalmei, Pommer, Mittelalter-Laute, Schlagwerk

08 - Do man den gumpel gampel sank [5:05]

Sänger 2, Blockflöte, Chitarra sarazenica, Dulcimer

09 - Meie dein lither schein [3:14]

Sänger 1

10 - Wie schöne wir den anger ligen sahen [4:03]

Sängerin, Sänger 1/2, Schalmei, Lira, Mittelalter-Laute, Schlagwerk

11 - Vreut euch wol gemuten kind [4:08]

Sänger 1, Blockflöte, Schalmei, Harfe, Schlagwerk

12 - Sumer deiner suzzen wunne [6:14]

Sänger 2, Blockflöte, Fidel, Harfe

13 - Winter deine mail [7:08]

Sänger 1, Blockflöte, Drehleier, Mittelalter-Laute

14 - Sie clagen das der winder [4:27]

Sängerin, Fidel, Mittelalter-Laute

Ensemble für frühe Musik, Augsburg

Sabine Lutzenberger, Sängerin, Blockflöten, Schalmei, Harfe

Hans Ganser, Sänger 2, Blockflöten, Schlagwerk

Rainer Herpichböhm, Sänger 1, Mittelalter-Laute, Chitarra sarazenica, Harfe

Heinz Schwamm, Fidel, Lira, Drehleier, Dulcimer, Schalmei, Pommer

Recording: Augsburg, Barbara-Saal, 7/90

Recording Producer: Reinhard Kiendl

Recording Engineer: Dietmar Vogg

CD-Mastering: Andreas Bittel

Ensemble Photo: Albert Rott Cover

Design: Manfred Glaser/Herbert Becker

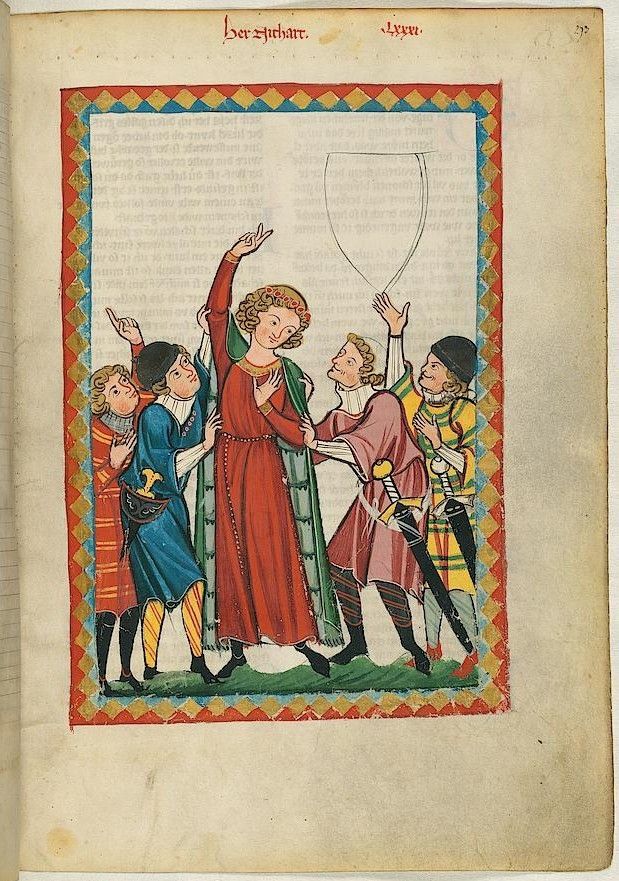

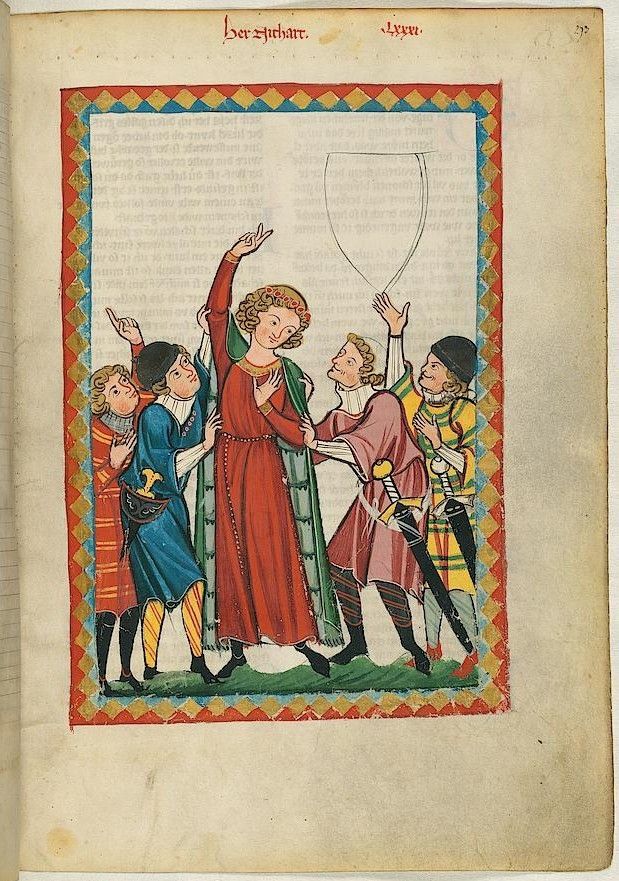

Cover Picture: Herr Neidhart, Codex Manesse Tafel Nr. 92 (273r), Insel Verlag Frankfurt 1988

Transcription and Musical Arrangements: "ensemble für frühe musik augsburg"

1990 / 1991 MusiContact GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany

Christophorus CHR 77327:

Neidhart von Reuental

Very little is known about Neidhart's life. Born in Bavaria at the end

of the 12th century, he travelled throughout the country as a wandering

minstrel, perhaps took part in a crusade and died around 1240 in

Mödling, a town near Vienna.

There is, however, one thing that can indeed be said about him:

Neidhart and his songs were extremely popular and well-liked.

Twenty-two manuscripts have been handed down to us with over 200 lyrics

and 55 melodies that were sung by him or by others who imitated

Neidhart's style. This oeuvre has simply been divided by researchers

into summer and winter songs, songs for dancing outside in the meadows

and songs for indoor dances. And indeed most of his songs do actually

begin with the socalled "Naturein-gang" - a stylized description of the

natural scene, as in 'Wie schön, daß der Mai mit Sonne,

Blumen, Gras, Vögeln wiedergekommen ist!" or "Wie schlimm,

daß der Winter mit Reif, Schnee, Frost eingekehrt ist!". After a

few lines or verses of such a convention, the songs, however, become

very individual in sound - songs that are virtuoso and expressive,

funny, boastul, erotic, obscene, brutal, complaining, nagging,

imploring - most of them with very catchy melodies which, after

numerous repetitions of numerous verses, creep into the ear and become

haunting tunes. And so it is that a closer look reveals a very

diversified picture of these summer and winter songs, numerous

variations and facets of the same theme, which is, namely, to strike up

a tune for dancing and to entertain and amuse the listener.

Heinz Schwamm

The Transmission of Neidhart's Songs

The transmission of Neidthart's songs differs fundamentally from that

of other Minnesingers:

1. Whereas the work of important Minnesingers has been preserved in

collected form in manuscripts such as the well-known "Manesse

Manuscript", Neidhart's songs were, from the start, also noted down in

special collections, but in manuscripts dedicated exclusively to the

author; the first of these was the so-called Riedegger Manuscript R

(around 1280).

2. At a time when the transmission of other German Minnesang virtually

disappears (15th century), important Neidhart collections continue to

appear, the foremost of which is the most comprehensive collection of

any Middle High German author whatsoever, the manuscript c - a kind of

complete edition of Neithart songs, written in the second half of the

15th century.

3. No other Middle High German lyrist has had so many melodies handed

down as Neidhart has. However, with the exception of the parchment

fragment O from the 14th century, the transmission of melodies does not

begin until the 15th century when paper came into use for manuscripts.

With the transmisson of such a great number of manuscripts from the

13th to the 15th centuries (several strophes even experienced the age

of book printing and were published in the Schwankbuch "Neidhart Fuchs"

in the 16th century), it is not surprising that in the songs handed

down in multiples one can find considerable differences in the number

and order of the verses (verse variants) and in the lyrics themselves

(text variants). There are, to a certain extent, even melodies to songs

written down twice and, as in the case of the texts, there are also

discrepancies here in these versions - variants that could, by the way,

possibly stem from the author himself. Consequently, it is possible

that Neidhart, in various places and on different occasions, performed

songs that had been altered. The content, style and form of Neidhart's

songs are also not uniform - a matter which can, in the case of such a

creative author, be easily understood when his ingenuity and forty

years of productive work are taken into consideration.

The diversity of the songs together with the idea prevalent in the 19th

century that handed-down material was "corrupt" prompted philologists

to examine it "critically". They used formal, one-sided schematisms and

the aesthetic-moral criteria of the 19th century to analyse the texts,

believing that it was possible to separate them into the categories of

"authentic" and "unauthentic". The texts thought to be unauthentic were

then designated "pseudo-Neidhart". And it is with this approach that

the philologists of the last century were able to exert an influence on

research that has continued up into our day and age.

It was not until recently that one has departed from the question of

authenticity as a central theme of Neidhart research, for the

distinction between authentic and unauthentic songs and - within a song

itself - into authentic and unauthentic verses is, principly speaking,

not possible. As a result, there has been a change in approach to

considering the oeuvre, which has been handed down as Neidhart's, in

its entirely (confer especially the work done so far by the

"Salzburger-Neidhart-Projekt" - a new complete edition published by I.

Bennewitz-Behr, U. Müller and F. Spechtler of all the lyrics and

melodies which have been handed down as Neidhart's; for the latest

developments in research confer G. Schweikle, Neidhart, Stuttgart 1990).

Consequently, in our recording you will not hear the "authentic"

melodies "critically cleaned" by the philologists of the 19th century,

but instead the songs with their melodies as they were written down in

the original sources. The above-mentioned wording and text variants

forced us, on the one hand, to make a choice and, at the same time,

gave us the opportunity to find "our" Neidhart with the present-day

listener in mind.

Lyrics and melodies were taken from the following manuscripts:

Hs. c: Staatsbibl. Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Ms. germ.

fol. 779

Hs. s: Sterzinger Miszellaneen-Handschrift, Stadtarchiv Sterzing,

Südtirol

Hs. w: Osterreichische Nationalbibl., Wien, series nova 3344

(Liederbuch des Liebhard Eghenvelder)

The translations are from: D. Kühn, Neidhart aus dem Reuental,

Frankfurt am Main 1988. Hg. S. Beyschlag / H. Brunner, Herr

Neidhart diesen Reihen sang, Göppingen 1989.