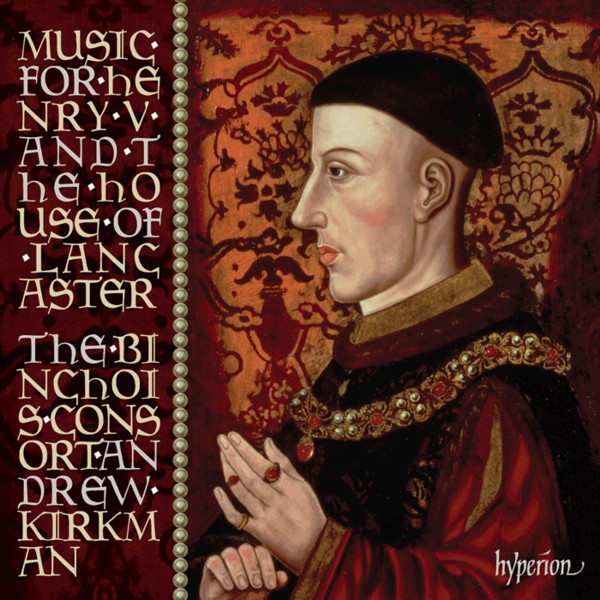

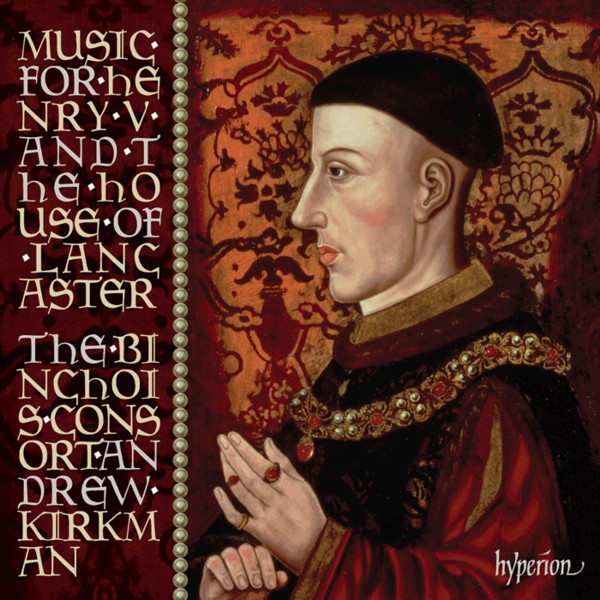

Music for Henry V and the House of Lancaster / The Binchois Consort

medieval.org

hyperion-records

Hyperion CDA67868

2011

grabado en mayo de 2010

St Silas' Church, Kentish Town, London

01 - 'Roi HENRY', Henry V (1386-1422). Gloria [3:42]

The Office for St John of Bridlington · antiphons &

responsory

02 - 'Johannis solemnitas digne celebretur' [7:05]

03 - Asperges me, Domine [2:41]

chant with faburden

Missa Quem malignus spiritus

04 - 1. Kyrie [6:59]

05 - 2. Gloria [6:28]

06 - Ave regina caelorum [1:15]

chant · solo, Richard Butler

07 - Leonel POWER (d.1445). Ave regina caelorum [2:53]

08 - 3. Credo [7:34]

09 - Gloriosae virginis [0:52]

chant · solo, Christopher Watson

10 - Leonel POWER. Gloriosae virginis [1:39]

11 - 4. Sanctus and Benedictus

[7:38]

12 - [Thomas?] DAMETT (1389/90?-1436/7). Salvatoris mater ~ O Georgi Deo care

[4:13]

13 - John COOKE (c.1385-1442?). Alma proles ~ Christi miles [3:50]

14 - [Nicholas?] STURGEON (d.1454). Salve mater Domini ~ Salve templum gratie

[3:04]

15 - 5. Agnus Dei

[6:18]

16 - Ite missa est ... Agimus tibi gratias [2:01]

17 - Tota pulchra es [2:02]

chant · solo, Timothy Travers-Brown

18 - Walter FRYE (d.1475). Ave regina caelorum [2:35]

The Binchois Consort

Andrew Kirkman

Mark Chambers, alto

Timothy Travers-Brown, alto

Richard Butler, tenor

Edwin Simpson, tenor

Matthew Vine, tenor

Christopher Watson, tenor

This recording documents in sound

something of the cultural seriousness and panache of the royal princes

of the House of Lancaster. Above all, it seeks to evoke the vocal and

ceremonial beauty of their household chapels. In doing so it celebrates

in music the brilliant, iconic figure of Henry V, hero of Agincourt and

the French campaigns; the obviously unheroic but still culturally and

religiously influential figure of his son, Henry VI; and finally the

perhaps unlikely figure they both revered: John Thwenge (Thwing), a

fourteenth-century Augustinian prior who, as St John of Bridlington,

was to be the last English saint canonized prior to the Reformation. It

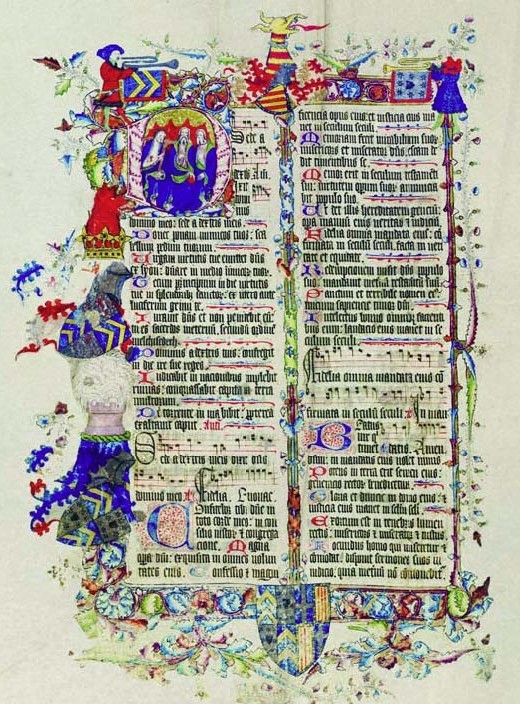

also celebrates the great Wollaton Antiphonal, a magnificent

illuminated chant book of the early fifteenth century that uniquely

preserves the melodies of the Bridlington Office and constitutes one of

the finest survivals of the myriad liturgical volumes of

pre-Reformation England, so very few of which avoided falling prey to

the purges and material destruction of the mid-sixteenth century.

Our programme presents a spectrum of English polyphonic vocal styles

spanning the reigns of Henry V and Henry VI, and we have sought to

balance the securely ascribed pieces (by both more and less familiar

names) with the anonymous ones. The programme as a whole articulates a

kind of journey through Lancastrian dynastic concerns, demonstrating as

it does so the sheer variety of types of singing, some of it virtuosic

in its brilliance, available to well-staffed princely chapels in

England at the time. More concretely, it offers sacred ceremonial

pieces written either for Henry V himself, as King, or to invoke the

saintly patron of the House of Lancaster, John of Bridlington, as well

as a group of motets in honorem beatae Mariae virginis.

The Bridlington Mass-setting recorded here dates from the era of his

son and heir Henry VI, though it may or may not have been commissioned

directly for (or indeed from within) the Chapel Royal itself. It is

based on one of the melodies found in the Wollaton Antiphonal (Quem

malignus spiritus), and is presented together with items of English

plainchant and a selection of motets chosen not just for their sonic

qualities, but to illustrate something of the range of styles in use

during the ‘Lancastrian decades’ of the fifteenth century.

These chants and motets are interspersed among the Mass movements,

sometimes as pairs of Latin texts addressed to the blessed virgin Mary,

sometimes as integral parts of the order of Mass. The opening sections

of the Bridlington Office, up to and including the Responsory which

provides the Quem malignus melody, are sung as a kind of

musical preface or introduction, beginning at Johannis solemnitas.

(As was common in Office chants of the Sanctorale, the various

component texts stay very close to the narrative of the life of the

saint whose feast was being celebrated, so that anyone listening or

participating would be reminded of the relevant stories as the liturgy

progressed.) The Asperges me, part of the penitential rite at

the beginning of Mass, is then performed to Sarum chant, with the

‘refrain’ being sung to improvised three-voice polyphony (a

widespread and characteristic tradition, known in England as

‘faburden’). The conclusion of Mass is marked by a short

‘post missam’ motet for three voices, Agimus tibi

gratias, that in time-honoured fashion answers the priest’s

dismissal Ite missa est (‘Go, the Mass is ended’).

There are three chant/motet pairings dedicated, rather like votive

offerings in sound, to the virgin Mary: Gloriosae virginis, Ave

regina caelorum and the much-loved Tota pulchra es, which

is paired with another Ave regina setting. There is also a

group of three extended motets addressed jointly to Mary and St George,

as prime intercessors for the kingdom of England (Salvatoris mater,

Alma proles and Salve mater). These motets, written by

musicians of Henry V’s own chapel, are without doubt political

pieces, in a religious and ceremonial sense, reflecting the bellicose

history of Henry’s reign with its central victory of Agincourt,

and the King’s vital position in relation to the English realm

and people at that momentous time. There were celebrations in London

following on from the victory itself—an event that was

mythologized almost as soon as it had happened, and had already passed

into national legend long before Shakespeare and Burbage, let alone

Garrick, Kean, Olivier and the rest. Motets played a key role in both

the quotidian and the occasional rituals of Henry’s reign, one

key event having been the performance of a (now lost) motet Ave rex

Anglorum / Flos mundi / Miles Christi—which no doubt

expressed sentiments similar to those of the surviving trio of

motets—before the gate to London Bridge to herald the

King’s entry into the city following his great victory in 1415.

The motets may well belong together as a group, which is how they

appear in the Old Hall manuscript, couched among the Sanctus and

Benedictus settings—and so this is how we present them here, at

the appropriate point within the Mass liturgy after the Sanctus (the

outer two are based on the two ‘halves’ of a divided

Benedictus chant, split at the word ‘ve-nit’). The central

motet has the invocation ‘Christ, defend us from our

enemies’, and makes a general plea for divine support for both

state and people, as well as for the King himself, in time of war.

The Missa Quem malignus spiritus is an extended cantus firmus

setting based on the chant extracted from the Bridlington Office. It

was evidently quite widely known and performed, surviving as it does in

as many as four sources (two of which are in fact the same version

copied twice). In particular, it survives (in only fragmentary form) in

the so-called Lucca Choirbook, a musically substantial manuscript

collection of great historical interest that was written circa 1463, in

Bruges, probably for use in the chapel of the English Nation of

Merchant Adventurers (whose governor William Caxton, a long-time

resident of Bruges, had recently become). The chant melody in

(relatively) long note values is given in the lower of the two tenor

voices, and in our recording has been sung to its original Bridlington

text. The high tenor and discantus parts form an integrated pair of

voices above this, and are written with a degree of rhythmic interplay

and melodic imitation that gives a sense of tautness and momentum to

the texture as a whole. This is exceptional, yet not uncharacteristic,

for English music at this period. It is becoming clearer, the more the

repertory is explored and investigated in greater depth, that there was

a really wide range of vocal idiom and compositional style operative in

England during this era. And the anonymous status of so many important

works, including such pieces as the Bridlington Mass and the iconic Missa

Caput, can only serve to sharpen our awareness of this situation,

standing as they do beyond what we (often too readily and uncritically)

see as the self-consistent personal styles of the best-known composers.

The Quem malignus Mass was evidently conceived for a skilled

ensemble of singers, whose art seems to have left its mark upon the

polyphony—its clearness of line, its sense of rhythmic focus and

balance, and the general elegance of its solutions to the problem of

presenting the liturgical texts in cogent phrases, while offering at

the same time a real sense of articulate musical flow, are all evidence

of this. It undoubtedly reflects the professional world of the

Lancastrian chapels, and those of the important noble families

associated with them (Beauchamp and Beaufort, for example). It is a

very individualized piece, and one not easily susceptible to close

linkage with others; perhaps the work that offers the closest points of

analogy is Frye’s beautiful Nobilis et pulchra Mass,

although this relationship ought not to be exaggerated. For the

present, the proud anonymity of the Missa Quem malignus spiritus

(like that of the Caput Mass, indeed) will remain one of its

distinguishing characteristics.

Like the Mass, the anonymous three-voice Agimus tibi gratias is

also found in the Lucca Choirbook. It is one of a group of (presumably)

English motets written together in the manuscript, that are for use at

the end of the liturgy (blessing and dismissal); and we may be certain

that at some time or other it was heard at Mass in Bruges together with

the Missa Quem malignus spiritus, the two being sung from the

manuscript they shared.

The four-voice motets Gloriosae virginis and Ave regina

caelorum are jewels of the art of Leonel Power. These pieces are

not long, but their sense of compactness is lightened and dispelled by

the exquisite control of line and sonority which they exhibit. Their

finely judged and ‘easy’ intricacy lifts them into a

time-dimension where a musical moment or phrase may be neither long nor

short, but simply of a perfect duration. Moreover their sound is

distinctive and individual, as well as beautiful—this is an idiom

unlike any other at that period, even in England, and creates a sense

of space and luminosity through the masterly interplay of its musical

elements. These short antiphon texts are set as a combination of votive

offering and gently impassioned invocation, freely alluding to their

respective chants as they do so.

The Frye Ave regina caelorum was one of the most widely copied

and evidently best-loved motets of the entire fifteenth century. It

survives in a wide range of sources, was depicted in visual art being

sung by angels, and was reworked in keyboard arrangements and with

expanded vocal textures. Our version is in four voices, and is

transmitted in a source as far away as late fifteenth-century Bohemia.

The chant for St John and the succession of the Mass are prefaced by a

Gloria, found in the Old Hall manuscript as one of two pieces by

‘Roy Henry’, very probably Henry V himself. That a royal

personage should have been a literate musician, no doubt well versed in

the arts of singing and musical leisure in addition to those of

composition, as well as being very conscious of the personal interest a

royal prince ought to take in the musical and ceremonial ordering of

his chapel, is on the face of it surprising. Yet as we have seen, the

Lancastrians offer, in the vigour of their cultural as well as military

prowess, the very archetype of a complete prince in a way that stands

as a model for the later Middle Ages, and yields nothing to the

princely ideal of later decades. In Henry V’s case, as in that of

Charles the Bold later in the century, this engagement with the art of

music was clearly a skilled and active involvement.

If the English music of the fifteenth century still has the power to

speak to us today, with its individuality of sound, its particular

beauty and sense of aesthetic priorities, then that is all of a piece

with the fame it enjoyed in its own time. For several generations it

was valued and performed both at home and abroad, occupying a leading

position on the European stage from Italy and France in the west to

musical communities far away in Germany and central Europe. It was sung

in the most prestigious chapels and ecclesiastical centres, but also in

far-flung places which one might hardly expect English music to have

penetrated. This was one of those few moments when English music was at

the very forefront of European developments, and was openly

acknowledged to be so by European masters. No group of aristocratic

patrons did more to foster the emergence of such a situation than the

princes of the House of Lancaster.

PHILIP WELLER © 2011

The Bridlington & Missa Quem malignus Project

THIS PROJECT grew out of a very specific, practical brief: to devise a

concert programme for an event that would celebrate in music the

process of conserving the Wollaton Antiphonal, and the new phase of

intensive study to which this process has given rise. (Parts of the

Antiphonal were shown in an exhibition of the Wollaton medieval

manuscripts which ran from April to August 2010 at the University of

Nottingham; there was a public research colloquium on the significance

of the Antiphonal for polyphonic music on 4 May followed by a one-day

conference on 8 May, together with the evening concert given by The

Binchois Consort.) The research, planning and preparation for the

concert opened up new areas of interest and significance and led to the

present recording, which brings the Bridlington material and its story

into close relation with Henry V, his son Henry VI, and the House of

Lancaster.

The House of Lancaster: Princes, Patronage, Music

As men and monarchs, Henry V and his heir Henry VI could scarcely have

been more different. Despite being father and son, and (in theory at

least) schooled to the same role and the same tasks, they were about as

dissimilar as could be imagined. Henry V was the great warrior, with

tremendous reserves of character and strength of purpose, whose

personality and achievement both on and off the battlefield became the

stuff of myth even in his own lifetime. The admiration he enjoyed and

the loyalty he commanded were of heroic proportions. Henry VI, by

contrast, was the would-be conciliator, whose gentler nature and

perhaps too-scrupulous indecision and anxiousness made him a weak

leader—a king at the furthest possible remove from his father.

Yet the two men were alike in their keen promotion of music. This was

especially true of Latin sacred music for the ceremonial operations of

the chapels they supported: the celebration of Mass and of Vespers, as

a sign of their princely dignity and the divine order of their earthly

rule. On this level, our concert and recording project has brought them

closer together than they ever were in life. For while they were

separated in history by the tide of events, and in posterity by our

rather fixed view of their divergent personalities and destinies, they

resembled one another in their keen appreciation and patronage of

polyphonic art music, and of the working musical institutions needed to

support it.

Between them, the Lancastrian princes—Henry and his brothers

Clarence and Bedford, essentially, and later the younger

Henry—employed most of the famous composers of the era at one

time or another. The sense of high-level collective musical endeavour

was crucial to the development of strong musical personalities, the

fruits of whose labours expanded the horizons not only of English but

of European music. The Lancastrians contributed to this in a huge way.

As royal figureheads, they brilliantly displayed an all-round package

of strengths, virtues and accomplishments: their aristocratic personae

and the organization of their entourage offered a palpable sense of

richness and dignity. This was part of the aura of power and kingship;

and their sense of display—including the best available sacred

music, sung by the best singers— helped to maintain that aura.

The functional needs of princely ceremonial, and the technical and

aesthetic needs of maintaining a brilliant musical establishment and

its associated repertoire, went hand in hand. Henry V may have been the

quintessential soldier and leader of men; but he also embodied to a

remarkable degree the arts of peacetime and good governance, too, as

the early fifteenth century understood them. He was in this sense an

important agent of cultural as well as political and military history.

In him we can easily observe how the nature of the man and the

performance of his role, with its many associated tasks and duties,

together contributed to the strong projection of his kingly identity.

His son Henry VI was by contrast no great leader, a peaceable man whose

reputation has understandably suffered by the comparison with that of

his father. But the younger Henry was among other things a religious

patron of great energy and commitment, the results of whose activity

(as distinct from his historical reputation) have in some instances

outlived and outshone those of his father—as for example in his

great collegiate foundations at Eton and Cambridge. And the fact that

many such colleges were from the very beginning set up as places where

polyphonic music was to be cultivated, and the relevant singing and

composing skills carefully nurtured, relates directly to the

flourishing state of English music throughout the fifteenth century, to

the vigour of its traditions, and to its international fame.

Lancastrian Devotion to St John of Bridlington

But there is a further strand to our project: the presence of St John

of Bridlington, the last English saint to be canonized prior to the

Reformation, and—chiefly through the agency of Henry IV—a

patron saint of the House of Lancaster. The Bridlington threads

contribute in no small measure to the colour and texture of our

tapestry. The early years of the fifteenth century saw an increased

attention given to English saints, not least by the Lancastrians. The

famous east window in the Beauchamp chapel at St Mary’s, Warwick

bears eloquent testimony to this: in the upper level of the window we

see, on the left, St Alban and St Thomas Becket, and on the right,

Saints Winefred and John of Bridlington. As major political and

administrative players in the affairs of the kingdom, the Beauchamps

were a key part of the network of alliance positioned around the House

of Lancaster, sustaining it and extending its influence. In such a

context, the presence of the ‘Lancastrian St John’ among a

group of English saints that was clearly intended to be representative

and emblematic is striking and significant. (It is easy to imagine any

of the professional male-voice ensembles employed by the

Lancastrian-related families as part of their household chapels singing

the Missa Quem malignus in the context of their liturgical

duties; musically it would have been very suitable for just this kind

of purpose—and it must surely have sounded in the chapel at

Warwick, in the presence of the richly coloured image of the saint

himself.)

Partly, the emphasis on English saints was a matter of cultural

identity; but it was a question of politics as well. National and

regional relationships were being renegotiated during the fourteenth

and fifteenth centuries, even as the Hundred Years War and the Wars of

the Roses were being played out (over decades, rather than years). The

exigencies of place and power formed part of this process of

renegotiation; and so far as the expression of loyalty and nationhood

was concerned, authority and solidarity resided as much in securely

located, culturally grounded religious tradition as in force of arms or

jurisdiction. This is one strong reason, no doubt, why the cult of John

of Bridlington became an important factor for Henry IV and his

descendants. He was a regional saint, whose shrine was within easy

striking distance of their ancestral stronghold at Bolingbroke in

Lincolnshire, and may well have been thought of as offering a kind of

resistance, or better: a kind of positive rivalry, to the rising cult

of Archbishop Scrope at York.

This was doubly important because Henry IV had had Scrope executed for

treason after the confrontation at Shipton Moor—and the last

thing he wanted was a renewal of the York-based rebellion in the form

of a popular uprising fuelled by religious feeling, and focused on a

local ‘martyr’ to the Yorkist cause. Such a sense of

urgency to match the strength of political and military power with the

strength of ceremonial and cultural display was accentuated for the

Lancastrians not least because they were usurpers. The energy with

which they pursued this was genuinely heroic; and there is little doubt

that their sense of the need to invoke divine aid, or at least seek

divine approval, was part of their way of dealing positively with the

dynamics of their situation.

The Lancastrian revolution (there is no other appropriate word) of 1399

brought them to power, but there was resistance on every side. The

psychological need to find, and feel, support from on high was probably

overwhelming. And there is no doubt whatever that Henry V did in fact

take his religious obligations, especially those towards the saints,

very seriously indeed; a devoutness stemming at least in part from the

moral exhortations of Thomas Hoccleve, whose Regement of Princes

had been written for him and presented to him prior to his accession,

in 1411, when he was still Prince of Wales. As in all things, however,

he fulfilled his duties not just pro forma but decisively, with heroic

energy.

On his royal tour in 1421 he made special pilgrimages to shrines he

judged of particular importance, including Howden, Beverley and

Bridlington in Yorkshire, as well as travelling from Lincoln to Lynn

and then Walsingham in Norfolk. It was thought that St John of Beverley

had intervened—or at least, interceded—on behalf of the

English so as to ensure the victory at Agincourt, and that his shrine

had sweated holy oil as a mark of this. (Agincourt was fought on 25

October which, in addition to being the feast of Saints Crispian and

Crispinian, as Shakespeare reminds us with insistence, is the feast of

the Translation of St John of Beverley, as observed in the diocese of

York; at Henry’s request Archbishop Chichele ordained various

forms of enhanced liturgical observance for St John the following year,

1416.)

PHILIP WELLER © 2011

The Wollaton

Antiphonal

As indicated above, the conservation project has been allied with new

historical and interpretive research on the Antiphonal. This research

is in turn framed within a larger project devoted to the collection of

medieval manuscripts of Wollaton Hall Library, where the Antiphonal

resided from the mid-sixteenth century until Christmas 1924. It

belongs, as it did in the later fifteenth century, to the parish church

of St Leonard’s; but it was as a result of having been kept in

the family library at Wollaton Hall that the Antiphonal miraculously

escaped the purges and destruction of the Henrician Reformation.

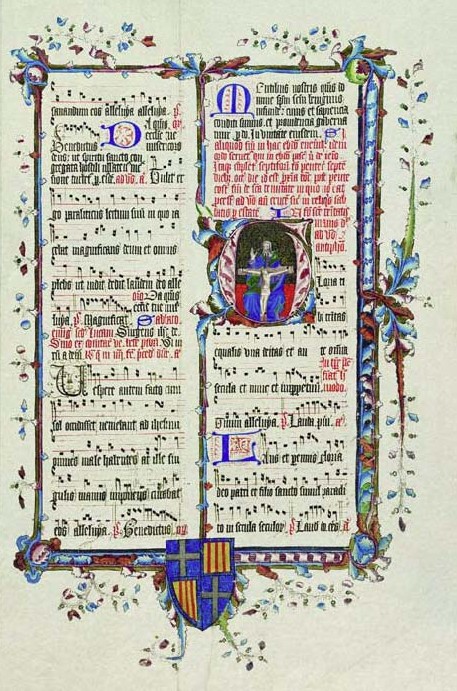

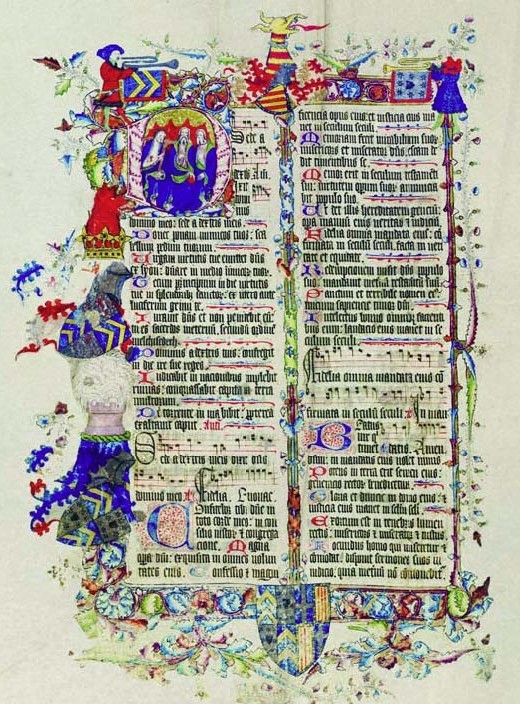

The Antiphonal is a sumptuous illuminated medieval service book

produced in the early fifteenth century (most probably in East Anglia)

for Sir Thomas Chaworth (1380–1459), an enormously wealthy

magnate and bibliophile, and one of the most prominent noblemen in the

East Midlands. Influential and very active in public life, in addition

to being rich and well connected, he was related to the

Plantagenet-Lancasters through a common ancestor, the first Sir Patrick

de Cadurcis (the original form of Chaworth), and seems to have

commissioned the genealogical additions to the famous Chaworth Roll,

that brought his very distinguished family tree up to date, in the

early years of the fifteenth century. This strong connection to the

House of Lancaster (as a young man he had fought at Agincourt with

Henry V, with a force of eight men-at-arms and twenty-four archers)

probably explains why he might have had a personal—and also

dynastic—investment in his devotion to John of Bridlington. He

would have sought to maintain and express that devotion as a mark of

his Lancastrian loyalty, as other great families such as the Beauchamps

and Beauforts would also have done. Moreover, he seems to have had a

special allegiance to the Augustinians: he was buried with his wife in

an Augustinian house, Launde Abbey in Leicestershire, where he had

previously founded a chantry. So there is every likelihood that the

Bridlington Office may have been copied (as a special addition) into

the Antiphonal at his instigation, some time between the book’s

completion circa 1430 and his death in 1459.

He may have viewed his prized liturgical manuscripts (in part at least)

as luxury cultural objects. Certainly, their visual and artistic

aspects were important to him. But there seems little doubt that he

valued them for their religious significance as well, perhaps even

primarily; and this then fits in very well with what we know of the

acts and attitudes of conventional piety that characterized his later

years. His combination of immense wealth with a genuine religious

sensibility was a fairly common one among the medieval nobility, and

quite naturally found expression in bequests to religious communities

and institutions, and in the purchase of extravagantly expensive

devotional and liturgical books. If the stylishly adorned Book of Hours

was the usual acquisition (the ‘must have’ accessory of

choice for fashionable devotion), the purchase of formal liturgical

books may not in itself have been all that rare, though the sheer size

and splendour of Chaworth’s Antiphonal must surely have been

exceptional.

Besides the Bridlington Office itself, entered on separate leaves of

vellum at the end of the Sanctorale, there are other additions

to the book that are specific to the Use of York, or to the Willoughby

family and to Wollaton in Nottinghamshire, which date from the later

phase of the book’s existence once it had passed into the

possession of the parish church of St Leonard’s, soon after Sir

Thomas’s death in 1459. It probably came to the church through

the good offices of Richard Willoughby (d1471) of Wollaton Hall (the

old hall, which stood close by the church), who was Chaworth’s

chief executor; and it was paid for out of the estate of the rector of

Wollaton, William Husse, who died in 1460. The close physical study of

the manuscript has opened up a new phase of interpretive and contextual

study, which is proving to be of real fascination and historical

interest. Handwritten changes are present in the Calendar, including

the addition of York feasts and the listing of Willoughby obits and

commemorations, and also the feast of dedication of Wollaton church.

Other handwritten entries, and the glorious heraldic illuminations,

tell their own story vividly; and it is the matching of these visual

elements with our knowledge of the book’s history that speaks

eloquently to us of the practical, everyday use to which it was put,

despite its extreme richness as a visual object.

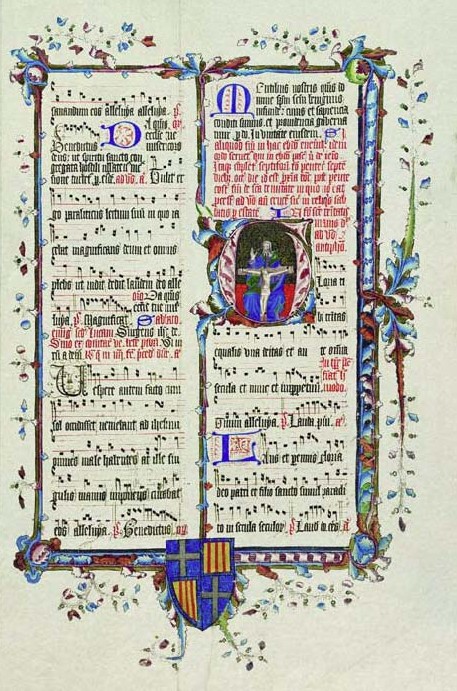

The written image of music has a fascination all its own. Not just the

striking visual character and precision of the notational symbols, and

also (in the best cases) the clarity and elegance of the script, but

the whole conception and layout of the musical book have the power to

fix our attention. And this is true whether the book is a liturgical

volume, a collection of polyphony, or indeed, in later music, a

composer’s autograph. The Wollaton Antiphonal demonstrates very

well the extraordinary beauty of the finest kind of liturgical book

production of the early fifteenth century in England. (It came, almost

certainly, from a skilled East Anglian scriptorium and

illuminator’s workshop around 1430.) The arresting mise en

page for the beginning of Psalm 109 (fol. 246v) displays the

technical virtuosity as well as the visual brilliance of the

illuminators. Its decorative scheme shows the Trinity, and also

illustrates some of the armorial designs which proclaimed the status

and pedigree of Sir Thomas Chaworth, the original owner of the

Antiphonal, and his wife Isabella. The image of the singing clerics

also illustrates the first verse of a Psalm text (Psalm 97, fol. 241v).

The page showing the beginning of the Office of the Assumption (fol.

369r) comes, like the Psalm leaves, from the main body of the volume,

while the two leaves showing sections of the Bridlington chant (fols.

411r-v) are an addition: they come at the very end of the Antiphonal,

appended to the section devoted to the feasts of the Saints.

As indicated elsewhere, the community of the parish church of St

Leonard’s, Wollaton were owners of the manuscript from 1460 and

again from Christmas 1924 when it was once more returned to their

possession. Were it not for the fact of their custodianship of the

Antiphonal, and of its having been kept safe in the interim in the Hall

library from the ravages of the Reformation, we would never have had

the music of the Bridlington Office at all, and our scenario would have

been much less complete. Thanks are due to the church for their

generosity in wishing to share what is in their possession, and for

participating in the telling of an extraordinary story. Thanks are due

as well to all those who have worked, both in the church and later in

the Nottingham University Library, to look after and maintain this

precious book, and finally, not least, to the man who—with no

little courage—took the first great plunge towards the immense

task of conserving the Antiphonal in its entirety: Nicholas Hadgraft

(1955–2004).

PHILIP WELLER © 2011