Tom Binkley, performer, teacher and recording artist, was one of the great gurus of early music.

A close colleague traces Tom's remarkable life and extraordinary influence.

The Several Lives of Tom Binkley: A Tribute

David Lasocki — Early Music America, Fall 1995, pp. 16-24

Tom Binkley,

performer, teacher and recording artist, was one of the great gurus of

early music.

A close colleague traces Tom's remarkable life and

extraordinary influence.

pdf

David Lasocki

An authority on

period woodwind instruments and their music, David Lasocki is Head of

Reference Services in the Music Library, Indiana University.

The Several Lives of Tom Binkley: A Tribute

Professor

Thomas Eden Binkley died on April 28, 1995 at his home in Bloomington,

Indiana, at the age of 63, after a distinguished career as a performer

and educator in the field of early music. What follows here is a kind of

amalgam —a survey of Binkley's life and work, a sampling of critical

opinion of his recordings and a gathering of comment from students and

colleagues about his performing and teaching. It will soon be clear that

what I have to say about this remarkable man is only the first word. It

is by no means the last.

Tom Binkley was born on December 26,

1931 in Cleveland, Ohio. This day of the year is known in Great Britain

as Boxing Day—an appropriate metaphor for Tom's style, as we shall see.

Tom's life cannot be seen in isolation, but rather, as Tom's widow,

Raglind, put it to me, "as the logical product of an unusual family."

His grandfather, Christian Kreider Binkley, former schoolteacher from

Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a poet and humanist, author of several books

and collections of essays, studied Chinese language and literature, and

translated the Tao Te Ching, while his wife ran a ranch and raised 11

children up in the hills of northern California. Tom's father, Robert

Cedric Binkley, Christian's oldest son, was an author and historian, a

Stanford graduate (like his father), who taught at Western Reserve,

Stanford, Harvard, and Columbia. One of his legacies—highly relevant for

early music—was the pioneering of microfilming as a way of preserving

documents during the 1930s. All three Binkleys shared the ability to

view their fields in broad perspective and to branch out at need into

other fields and cultures, studying them intensively, learning them

thoroughly and integrating them into their work.

Musical Beginnings

The

musical influence on Tom came from his mother's side. When Tom was only

9, his father died of cancer. His mother, Frances Williams Binkley,

moved Tom and older brother Robert to Boulder, where she worked as the

Social Sciences Librarian at the University of Colorado. She was a keen

amateur pianist. Her sister, Jean Williams, taught the piano at Sarah

Lawrence and had enjoyed the distinction of one concert at Carnegie

Hall; she often visited the Binkleys during the summer. Tom and Robert

both played in junior high band, then high school band. Tom began on

baritone horn, later switching to the trombone. Although he was not

considered a particularly outstanding player, it is noteworthy that

Henry Cowell, an old friend of Tom's parents from Stanford

days, wrote a well-known piece for baritone horn and piano in quasi-Baroque style called Tom Binkley's Tune

(1947). The Binkley brothers both played folk music—not cowboy or

country— on the guitar. Tom extended his musical experience in a dance

band that played in local towns, his party trick being to play the

trombone and smoke a cigarette at the same time. Still, he was better

known to his contemporaries for his skill on the football field than for

his music.

Ever restless, after high school Tom moved to New

York, where he took a series of odd jobs. He was a night guard at a

hospital, and was fired as bottle washer at a dairy when the foreman

caught him memorizing Persian vocabulary rather than washing bottles.

What impressed his daughters most in later life was that he had been a

New York taxi driver. He briefly joined the Marines, receiving an

honorable discharge when his elbow was injured—a fortuitous injury,

because it forced him temporarily to give up the trombone and

concentrate first on the guitar, then on the lute. Back in New York he

took lessons from a friend from Colorado days, Joseph ladone, now a

graduate of Paul Hindemith's Collegium Musicum at Yale University, and

certainly the most accomplished lutenist in America before the

generation of Paul O'Dette.

At the age of 20, Tom made a commitment to study music and went to the University of Illinois, receiving a B.M. cum laude

in 1956. Among his distinguished teachers were the musicologists Dragan

Plamenac, Claude Palisca, John Ward, Thrasybulos Georgiades, and George

Hunter. Tom, playing not only the lute but recorders, the shawm and

other medieval woodwinds, was one of the performers in the vintage-year

George Hunter Collegium Musicum which recorded the complete secular

works of Guillaume de Machaut for the Westminster label in 1954

(released in 1956). Even at this stage Tom had worked out some

imaginative lute accompaniments to the monophonic pieces. Hunter was an

inspiring teacher, whose musicianship Tom also admired. Hunter was also

open to Tom's ideas, which had an important influence on the group. By

the completion of a postgraduate year at the University of Munich on a

Fulbright Scholarship, Tom knew enough about lute technique to give a

lecture on the subject at an international conference. Then he returned

to Illinois for a year, bypassing the master's degree to work toward a

doctorate but never completing the degree.

The Studio

Instead,

Munich beckoned again, and Tom took back with him another Illinois

graduate student, Sterling Jones, who played vielle and viola da gamba.

At first they were members of Capella Monacensis, an early music group

run by a wealthy amateur lutenist named Weinhöppel. But the relationship

quickly soured, largely because Tom already had his own strong ideas on

performance. Tom and Sterling set up their own group, called at first

Studio für Alte Musik [Studio for Old Music], which had been the name of

Weinhöppel's concert hall. Some legal wrangling led Tom to rename the

group Studio der Frühen Musik [Studio of Early Music], which was close

enough to the original name that in Bavaria they had to perform as the

Internationales Studio der Frühen Musik for a number of years until the

fuss died down. In English-speaking countries they went by the name

Early Music Quartet. The other two original members of the Studio were

Andrea von Ramm, Estonian mezzo-soprano, and the British tenor Nigel

Rogers. Because of this international makeup, beginning in 1961 the

Goethe Institut (which played a part in German cultural exchange

programming like that of the State Department's United States

Information Agency) sponsored the Studio's tours—to the Far East and

South America. Then agents took over. Nigel Rogers left after a few

years to take up a solo career and was replaced by the American tenor

Willard Cobb. Cobb in turn was replaced by the countertenor Richard

Levitt, also an American.

The Studio adopted a professional

attitude from the start. Tom told me once that the group had spent the

first six months tuning, but Sterling Jones says that was largely

because they were trying, unsuccessfully, to get their consort of

Steinkopf crumhorns in tune. (How many other groups had the same

experience in those days!) The Studio rehearsed every day for two or

three hours virtually year-round. The group went on tour for nine months

out of the year, then spent the other three months recording in Munich.

Tom and Andrea, whose ideas meshed immediately, were always on the

lookout for something new. Each year, the Studio offered two or three

brand-new programs which it would take on tour, and it made one or two

recordings per year, often adding other soloists. (Alas, distribution

problems in the United States and Great Britain meant that a good many

of these recordings were not released in those countries and in some

cases have never been reissued there). Earning money solely from

concerts and recordings, with token support from the State of Bavaria,

the Studio's members lived from hand to mouth, always plowing back any

profits into the business, for music, books, and instruments. Like other

groups trying to entice the public into listening to medieval music—and

in those days it wasn't easy—the Studio began by "tripping through a

garden of goodies", as Sterling puts it. Then the foursome developed

longer, more integrated programs and started to give performances of

complete songs rather than playing and singing only a strophe or two. In

later years, they also strove not to change instruments as often from

piece to piece. Tom's ideas on lute accompaniment evolved—accompaniment

being a test of his composing as well as his technical skills—and he

made many exciting arrangements of entire works from the repertoire.

Most of the Studio's recordings, particularly of medieval music, met with critical acclaim. Just a taste:

The groundwork — the editing of original manuscripts and early printed editions — is extremely scholarly; the end

result, however, is anything but stuffy, especially when presented with

as much imagination, animation, gaiety, and down-to-earth humor as one

hears here. (Igor Kipnis on Bauern-, Tanz-, und Strassenlieder in Deutschland um 1500)

Instrumentalists

in various past and present Eastern and Middle Eastern cultures reached

high levels of technical proficiency without any apparent help from

Western European musicians. Thus it is possible that in medieval Europe

there were some musicians with an instrumental skill similar to that of

the members of the Studio der Frühen Musik. One merely questions whether

it is likely that so many of them happened to meet and reach such a

high level of ensemble work. (Hendrik VanderWerf on Chansons der Troubadors)

It

is particularly laudable that all the chansons are sung entire: without

this, much of their character would be lost, as it is on many attempts

to offer more songs but with only a sample verse of each. The musical

power of these songs comes through on this record which, given the

scholarly imponderables, is a fine achievement. (Margaret Bent on Chansons der Trouvères)

My

own feeling is that while they probably cannot claim any authenticity,

the songs in this form come alive in a way that plainer versions do not.

(Denis Arnold on French Songs of the Thirteenth Century)

The

Studio never used the word "authentic" about its performances. Rather,

Tom would inform himself fully about the historical evidence of how a

certain repertoire was performed, try to furnish plausible historical

instruments for the job, then take his inspiration from the texts and

the instruments to make additions in what he felt was the spirit of the

music. Still, there was always the practical limitation that the

arrangements had to fit the size and talents of a group which needed to

make a living. A tour in north Africa introduced the group to a variety

of exciting folk instruments that had remained the same for centuries,

and therefore seemed appropriate for Iberian and southern French music

of the Middle Ages (the miniatures of the Cantigas de Santa Maria

show Arab and Western musicians side by side). Tom was also impressed

by the musicianship of the Arab musicians and borrowed rhythmic patterns

from them wholesale. Although the Studio became famous—even

notorious—as the group that played medieval music in an Arab style, the

genesis was therefore, according to Sterling, "a kind of accident". In

any case, Tom said he did not want to be remembered for this feature of

the Studio's performances.

Both the mixing of cultures and the

desire to find the right performers for the job contributed greatly to

the success and excitement of the Studio's recordings. For example, Tom

wanted to show that the ancient Occitanian language is still alive in

the south of France. So he hired Claude Marti, a folksinger well known

to large audiences at summer festivals in southern France, to

collaborate on the recording L'Agonie du Languedoc, which contains heartrending accounts of the Albigensian Crusade.

Four Years in Basel

By

1973, travel costs were eating up much of the Studio's budget, and the

constant touring was making life difficult for everybody. Then, after a

performance in Basel, Wulf Arlt, the director of the Schola Cantorum

Basiliensis, offered Tom a position. Tom accepted, on the condition that

the entire quartet be included. Three non-musical highlights of Tom's

life in Basel were his marriage to Raglind in 1973 — in fifteen minutes

snatched between rehearsals for a recording—and the births of their

first two daughters, Leonor (1974) and Isabel (1976).

Tom's four

years at the Schola afforded him the scope to develop his ideas about

teaching and a larger ensemble than the Studio to work with regularly.

He insisted on two hours of rehearsal for each class every day, an

unprecedented amount for a school geared to private lessons. Eventually

the differences between the two approaches loomed large. At about the

same time, the Studio itself broke up, because of personal differences

and because it was hard to know in which musical direction to go next,

after all that they had accomplished. Sterling Jones believes that if

the group had been willing to repeat the same performances over and

over, the Studio could have done well financially at long last, but that

Tom's and Andrea's restless temperaments would never have allowed that.

Back to the Land in California

The

year 1977 therefore saw the Binkleys move to California. Tom had

decided to pursue the then-fashionable dream of homesteading. The

Binkley family property—440 acres near the top of a mountain, with

springs but without a house—was an ideal place to do it. For several

years, whenever he had toured in the U.S., Tom had returned to Basel

with stacks of Organic Gardening and Mother Earth News.

Not only did he devour books on construction, electricity and plumbing,

but with their aid he actually mastered the basics of each trade. He

came alone in April, hired a bulldozer operator, built a road to the top

of the mountain, flattened the site, bought a trailer, and piped in

water from the springs. One of Tom's uncles—part of the large Binkley

clan living on the adjoining properties—had planted a kitchen garden and

fenced it off from the deer. When Raglind and their daughters arrived

in June, the place was habitable. They all found the spot enchanting,

far away from the city lights, with long vistas over the valley and the

calls of coyotes in the distance. Believing they were going to be there

indefinitely, they did not build at once. Instead, Raglind recalls, they

made a large batch of elderberry wine. The following year, however, Tom

bought a kit for a hexadome, a variant of the geodesic dome, and set up

the basic structure with the help of his uncles and a "barn raising",

The tenor Harlan Hokin, a student from the Schola, came for a while to

help level the ground and build the dome, sleeping in his Volkswagen

Beetle. Before going off to a workshop in Boston, Tom made sure to give

another visitor, his guitar-playing nephew Paul Binkley, a crash course

in shooting a .22, in case Raglind and the little girls were threatened

by a rattlesnake.

Music, Indiana and the Early Music Institute

A

workshop in Boston? Yes, the world of music began to call Tom back.

Invitations started to pour in. The family spent two winters in Palo

Alto while Tom taught at Stanford. Despite the inaccessibility of the

Binkley property, musical visitors from the U.S. and Europe were given

to dropping by, sometimes unexpectedly. In 1979, two Indiana University

students, Cheryl Fulton and Roy Whelden, drove out there and asked to

study with Torn. Liking what they found, they went straight to Charles

Webb, Dean of the School of Music at IU, and persuaded him to make Tom

an offer. Tom immediately saw the potential of IU, the largest music

school in the country. Stanford was stimulating intellectually, but

really too small to allow large-scale performances. IU's vast pool of

music students offered Tom an enormous performing and teaching

challenge. The need to make money to buy building materials, which had

risen in price since Tom had started homesteading, also entered into the

Binkleys' decision. Supposing that it was to be for only two or three

years, the family set off for Bloomington, Indiana. But the university

has a way of drawing you in....

At IU, Torn set up the Early

Music Institute, a quasi-independent body within the School of Music,

and became its director. The status of the EMI has allowed it to seek

funds from both the School of Music and outside sources, including the

Mellon Foundation, three scholarship funds managed by the Indiana

University Foundation (the Jason Paras Fund, the Willi Apel Fund and the

Joseph Garton Fund) and the Foundation itself.

The

early 1980s were a madhouse. Tom taught, conducted and ran the EMI with

no secretarial help, the phones ringing nonstop and the usual visitors

descending on no notice. At home, he worked constantly in the evenings

and on weekends. Even after Tom acquired a full-time assistant in 1988,

the frenzy continued without letup. Tom always had a million projects

going on at once and tended to flit from one to another in the profound

conviction that every one of the projects was important and that all,

somehow, had to get done. He was always spontaneous, always in the

moment: "Do it now" was the watchword, whatever "it" may have been. He

hated bureaucracy with a passion, seeing rules, regulations and

procedures as a series of obstacles to his creative ideas. He battled

continually, saying what he thought, not worrying what people might

think of him, and never, never giving up. Occasionally, growing tired of

the latest piece of bureaucratic lethargy, he would announce, "I'm

going to do something scandalous", then wait for the reaction it

invariably produced. Not for Tom the way of tact and diplomacy. If his

student assistants worked hard, he gave them more and more work to do;

if they were poor workers, he gave them nothing. He disliked making

decisions about details. Needless to say, these methods did not make it

any easier to run a complicated organization that had to organize

private lessons, courses, auditions, workshops, rehearsals and

performances.

This maelstrom of activity, and the gallons of

coffee that kept it churning, would fortunately subside with the end of

each academic year. During the summers, Tom would spend three months at

the Binkley California property. At first, his family would accompany

him, but after his third daughter, Beatriz, was born (in 1981), Tom

would make the trip by himself and Raglind and the children would join

him later. There on the mountain, he exercised his construction skills,

adding such improvements to the dome as solar panels and a new wing. He

also built an addition to the family's house in Bloomington. One young

man, arriving there for an audition, was met by Tom on the roof with the

invitation to "Come on up and talk to me while you do some work".

Out of Chaos, Three-part Accomplishment

Out of Chaos, Three-part Accomplishment

Despite

the recurrent chaos at the EMI during Tom's 15 years as director, his

zeal and industry helped him bring to fruition an enormous crop of

creative ideas. First of all, he took the research purpose of an

Institute seriously. Seeing both the need and a market, he approached

the Indiana University Press with the idea of creating two series of

publications. Music: Scholarship and Performance consists of books on early music and its performance practices. Publications of the Early Music Institute

is a series of editions, translations of early treatises and practical

books. Tom somehow made time to act as editor of both series. With the

aid of a Mellon Foundation grant, he also established what is now called

the Thomas Binkley Archive of Early Music Recordings, at the Music

Library of Indiana University.

Privately, he encouraged research

behind the scenes. One day he came to see me and, without so much as a

"Hi, how are you?" he snapped: "David, you've written entirely too many

articles". Because this could be taken in two ways, I was stunned into

silence. Then he clarified his statement: "You need to work on some

large-scale projects, write some books". When I explained that I was

trying to write a book at that very moment, he promptly offered to look

at the typescript. He read several hundred pages in a couple of days,

gave me some sage advice on how to make it more marketable and even

suggested which publishers would be suitable for it. As a result of

Tom's intervention, I changed the direction of my book and did indeed

find it a publisher.

Secondly, Tom continued to record. He

established Focus Records, a label associated with the EMI that featured

performances by its present and former students. Touchingly, Tom also

reached back to the students of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis during

these years, using them in several recordings for other labels. He

expected, and was generally accorded, a professional standard of

performance. A pair of recordings of the same work, the Greater Passion

Play from Carmina Burana, made in the same year (1983) by the

groups from Basel and Bloomington, constitute a fascinating comparative

document (see the perceptive review by J.F. Weber in Fanfare,

11/12 1984, pp. 321-22). The list of recordings of IU performances

contains no fewer than 45 entries, clear evidence that under Tom's

direction the singers and instrumentalists of the EMI were privileged to

take part in presentations of a wide range of early music, from the Cantigas de Santa Maria

to Bach cantatas and a Handel opera. Two of Tom's large-scale dramatic

performances were among the most moving I have ever heard: Luigi Rossi's

Orfeo (1988), well received by the national critics, and Carmina Burana (1990), in (of course) a brand new version.

Thirdly,

Tom conducted classes. On paper, his courses covered many topics, but

in practice the topics tended to blend or even blur. Would we expect

otherwise from a man who lived so much from moment to moment? A class

labelled Lasso might begin with plainchant and wend its way for

several weeks through the Middle Ages and Renaissance before reaching

its ostensible subject. Quoth Tom: "How can you understand Lasso without

plainchant?" He brought all his pugilistic skills to bear on his

students, and it was not long before a new verb was added to the English

language: to be Binked. When you were Binked, as many students have

told me, you wanted the floor to open up and swallow you. Tom the Bink

bullied, cajoled, scolded, quizzed, contradicted himself—on purpose or

because it was a new and different moment—threw out koans in the manner

of a Zen master and metaphorically hit his students on the head with a

bamboo stick besides. He wanted to befuddle and mystify his listeners,

confuse their logic, open them up, educate them in the true sense of the

word: to draw out.

Binking and its Consequences

Angela Mariani, presenter of the syndicated WFIU early music radio program Harmonia,

passed along a Binkley anecdote that its co-protagonist, dazed at the

time, still doesn't quite remember. Angela was there in the classroom

when this individual, a student with a particularly logical turn of

mind, had for several minutes been pressing Tom for a logical answer to

some point of performance practice—an answer which of course was not

forthcoming. In exasperation, although quite instinctively, the student

let his pencil fly out of his hands in Tom's direction. Without missing a

beat, Tom caught the pencil and put it in his pocket. When the student

later asked another too-logical question, Tom shot back: "It's hard to

take notes without a pencil!" and flung it back over the student's head.

The feat was at least as stunning a display of virtuosity as playing

the trombone while smoking a cigarette, and far more instructive.

Angela

told me another revealing story. In the fall of 1994, Tom organized a

conference in Bloomington for Collegium Musicum directors from around

the world. At one session, the conferees were going on and on about

educational philosophy. When Tom's turn came, the sage, dying from

prostate cancer and barely able to sit in a chair, remarked simply: "My

educational philosophy is to form the mind so that it never believes

anything". It stopped the show.

As a conductor and ensemble

director, Tom put his students through the same process of discovery

that he imposed upon his students in the classroom. If a performer was

playing badly, Tom would look down and pull on his beard. "Why did you

play that A?" "Think of five other ways to play that phrase". Or

bluntly: "You didn't think about it enough". He never told you one way

to do something—or if he did, you could be sure he would contradict it

at the next rehearsal. A "But you said such-and-such yesterday", was met

with a barked "That was yesterday".

I asked Kim Pineda, an

accomplished traverso and recorder player who sang in the EMI's Pro Arte

for three years, what he had learned from Tom. Kim answered that he had

been inspired to do his best, even when he didn't feel like it. He had

learned to play the traverso more vocally, to see the musical line and

the big picture. Having come back to 18th-century music after performing

earlier music, he saw it with new eyes. Faced with Tom's challenge

"You'll come around to my way of thinking", Kim had been compelled to

think for himself. He had absorbed Tom's method of gathering all the

possible information, sorting it out, then going all-out for what he

wanted. He remembered a few of Tom's aphorisms: "I can take this piece".

"Speed doesn't kill if you know how to drive"— an admonition not to let

technical limitations determine your tempi.

Of course, Tom's

methods were not equally successful with all students. For example, each

of the four members of Bimbetta I interviewed—Andrea Fullington, Sonja

Rasmussen, Allison Zelles and Kathryn Shao— had very different reactions

to Tom's tutelage. Sonja voiced the negative view. She believes that

Tom made insufficient allowance for his performers' being students,

unrealistically expecting instant professionalism, at least on

commercial recordings. In class, he too often assumed that his students

were Binkleys in miniature. His disorganization and lack of attention to

bibliographic detail were frustrating, and his flitting from subject to

subject drove her to distraction.

Of course, Tom's

methods were not equally successful with all students. For example, each

of the four members of Bimbetta I interviewed—Andrea Fullington, Sonja

Rasmussen, Allison Zelles and Kathryn Shao— had very different reactions

to Tom's tutelage. Sonja voiced the negative view. She believes that

Tom made insufficient allowance for his performers' being students,

unrealistically expecting instant professionalism, at least on

commercial recordings. In class, he too often assumed that his students

were Binkleys in miniature. His disorganization and lack of attention to

bibliographic detail were frustrating, and his flitting from subject to

subject drove her to distraction.

Andrea Fullington had quite a

different reaction. Having been accepted at the EMI on the strength of a

good audition, she found that the stress of moving to Bloomington from

California had left her virtually unable to sing for two months. Tom,

far from being harsh, went out of his way to reassure her that he knew

she was under strain and that for now he was making no judgment of her

singing. Of course, once she recovered her voice he began to put typical

Binkley pressure on her. He would quip that if you couldn't survive

under pressure, you would never make it in the music business. Even so,

Andrea found Tom encouraging and inspiring from the start. "If you

didn't crumble", she said to me, "then he paid attention to you". She

appreciates the fact that he respected her for disagreeing with him when

he forced her into an argument.

Allison Zelles's reactions were

more mixed. At first, Tom told her that she was not developing her own

mind and personality but was hanging too much on Andrea's coattails. He

wanted something larger from her, something more in the way of

commitment. Allison felt that Tom had doomed her career. So she angrily

quit school, taking three incomplete grades, and left Bloomington and

music alike. But then she discovered the harp and "fell in love with

music again". After she dealt with the issue of her own commitment, she

returned to the EMI and again worked with Tom. She found his methods

harsh but respected his goals and felt that he really cared about his

students.

Bimbetta's harpsichordist, Kathryn Shao, found Tom

trying but now values the experience of working with him. He expected of

students, in her words, that they "wouldn't have a life outside of

class", that they would always be free to absorb material quickly. He

made unrealistic demands, like the injunction to read a whole treatise

by the next day. "Then he would say that he had really just wanted you

to read two articles mentioned in the bibliography". He constantly

changed his mind about how to perform a given work, finding several ways

that were meaningful and musical. But this insight into the reality of

multiple musical meaning is very useful to Kathryn now, helping her to

keep her spontaneity.

Interestingly, Kathryn, Andrea and Allison

all commented on Tom's expectation that they memorize everything—not

just in performing but in life. He believed in the power of the oral

tradition. They see this as an ideal and strive to follow it.

Eva

Legêne, the teacher of recorder at the EMI and now also a member of the

Indiana University woodwind faculty, made clear to me how important a

figure Tom had been in her life. She had first encountered him at

Stanford in the 1970s. She had taken his classes, but had known too

little about medieval music to benefit from them and in any case had

been unable to keep up with the workload. The doctoral students in the

classes—among them such well-known figures as Julianne Baird, Jason

Paras, and Sally Sanford—could keep up only by spending their whole

lives studying.

In the mid-1980s, when Tom wanted to hire a

recorder teacher for the EMI, he insisted that Eva was the one he

wanted. Circumstances did not allow her to come at once, but he told her

he could wait. (Tom once remarked to me that he liked her recorder

playing better than anyone else's in the world).

Eva found life

with Tom in the EMI very hard, although in retrospect beneficial. Like

her own father, Johannes, Tom was highly principled, unbending,

uncompromising, always demanding that people be creators, not consumers.

Tom's mind was so active that it was hard for him to listen to other

opinions, although he would listen when forced to. She admired Tom's

idealism but felt that he lacked compassion, at least until near the end

of his life, when his illness softened him. Whenever she went to Tom

for ideas about the programs of X060, the Renaissance ensemble she

directed, he was highly stimulating. During the preparation of a

performance, he would throw everybody into a panic, certain that people

always did better when their adrenalin began pumping. "You wondered how

on earth it could come together", Eva told me, "then at the last moment

he would pull the rabbit out of the hat—magic".

As for Tom's

outrageous administrative style, Eva had always asked people who

complained about it: "Who would you rather have as the director of the

EMI? An artist or an administrator?" The answer was, of course, clear to

everyone.

When Tom retired from EMI in January, 1995, at last

too sick to continue, "The place felt empty from the moment he left".

Eva's sense of loss was —and is—shared by many. But EMI continues: the

distinguished gambist Wendy Gillespie is acting director; and a search

for the new director will soon begin.

Binkley on Binkley

In the liner notes for a 1973 LP of Landini's music, Tom struck a whimsical biographical note. "Thomas Binkley

was

born in Ohio, the son of a historian. As a boy, he wanted to become a

dancer, but his parents objected. Later, he studied the science of

music, became a research assistant, and took part in early attempts at

computerized music. He translated a book about psycho-acoustics, and

wrote several monographs. In the end, he exchanged the university for

the stage. Today, as [researcher] and artist at the same time, he is

working on performing techniques and stylistic improvements in music of

the Middle Ages. But he would really rather have been a gardener". In

the next 20 years, as we have seen, he did become a musical gardener,

cultivating both the university and the stage. His one regret late in

life was that he had not done more writing. Musician, scholar, gardener,

builder, metaphorical boxer, dancer, linguist, homesteader, wine maker

and connoisseur extraordinaire—Tom was gifted far beyond most mortals.

His legacy is the stimulus, challenge and inspiration he brought

directly to his students and colleagues and indirectly to the thousands

who heard him in live performance and who continue to listen to his

recordings. Many important early music performers active today grew in

Tom's musical garden, including—to name only a few — all of Sequentia

(Ben Bagby, Barbara Thornton, and Elisabeth Gaver), Paul O'Dette and

Catherine Liddell. His music will live on in theirs. Truly, we have all

been Binked. And we're all the better for the Binking.

Tom Binkley's Writings

Articles and Forewords

· "Le luth et sa technique." In Le luth et sa musique. Neuilly-sur-Seine, 10-14 septembre 1957,

ed. Jean Jacquot, pp. 25-36. Paris: Editions du centre national de la

recherche scientifique, 1958; 2nd ed. rev. & corr., 1976.

· "Electronic Processing of Musical Materials." In Elektronische Datenbearbeitung in der Musikwissenschaft ed. Harald Heckmann, pp. 1-20. Regensburg: Gustav Bosse, 1967.

· "Zur Aufführungspraxis der einstimmigen Musik des Mittelalters," Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis 1: Sonderdruck, Winterthur: Amadeus, 1977.

· "The Greater Passion Play from Carmina Burana: An Introduction." In Alte

Musik: Praxis und Reflexion. Sonderband der Reihe "Basler Jahrbuch für

Historische Musikpraxis" zum 50. Jubiläum der Schola Cantorum

Basiliensis, ed. Peter Reidemeister and Veronika Gutmann, pp. 144-57. Winterthur: Amadeus, 1983.

· "Der szenische Raum im mittelalterlichen Musikdrama." In Musik

und Raum: eine Sammlung von Beiträgen aus historischer und

künstlerischer Sicht zur Bedeutung des Begriffes "Raum" also Klangträger

für die Musik, ed. Thiiring Bräm, pp. 47-58. Basel: GS-Verlag, 1986.

· Foreword to Willi Apel. Medieval Music: Collected Articles and Reviews. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1986.

· "A Perspective on Historical Performance," Historical Performance 1, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 19-20.

· Foreword to Willi Apel. Renaissance and Baroque Music: Composers, Musicology and Music Theory. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1989.

· "The Work is not the Performance." In Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Music, ed. Tess Knighton and David Fallows, pp. 36-43. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1991; New York: Schirmer Books, 1992.

· "Die Musik des Mittelalters". In Musikalische Interpretation. Neues Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, Band 11, ed. Hermann Danuser, pp. 73-138. Laaber: Laaber

Verlag, 1992.

Series Editor

· Music: Scholarship and Performance [Indiana University Press]

· Publications of the Early Music Institute [Indiana University Press]

Tom Binkley's Recordings: A Sampler.

Lack of both time and space

make it necessary to supply, not a full discography but rather a

preliminary sampler of Tom Binkley's recordings. I hope to bring out a

comprehensive discography in due course, and would welcome additions and

corrections from readers c/o Early Music America. My thanks to Raglind Binkley, Deborah Kornblau, and Angela Mariani for their extra help with this checklist.

1964 Carmina Burana: 20 Lieder aus der Originalhandschrift um 1300.

SdFM, MM. Recorded 21-25 July 1964. LP: Telefunken Das Alte Werk SAWT

9455; 6.41184 AW. PIN. Reissued 1987 CD: Teldec Das Alte Werk 8.43775.

Reissued 1989 as Carmina Burana, Vol 1, CD: Musical Heritage Society MRS

512434L.

1968 Carmina Burana II. 13 Lieder nach der

Handschrift aus Benediktbeuern um 1300 = Carmina Burana (II): 13 Songs

from the Benedikt beuern Manuscript circa 1300. SdFM+. Recorded Oct 1967. LP: Telefunken Das Alte Werk SAWT 9522-A; 6.41235. 1988 CD: Teldec Das Alte Werk 8.44012.

1972 Johannes Ciconia, Italienische Werke; franzözische Werke; lateinische Werke. SdFM. LP: EMI IC 063-30 102. Reissued as Geistliche und Weltliche Werke 1991 CD:

CDM 7 634422.

1972 Oswald von Wolkenstein, Moophone Lieder; Polyphone Lieder. SdFM. Recorded 21-23, 27-29 Dec 1970. LP: EMI Reflexe 1C 063-30 101; Cass: IC 263-30 101. Reissued as Lieder 1989 CD: EMI Reflexe CDM 7 63069 2.

1972 Guillaume de Machaut, Chansons I. SdFM, choir. Recorded Sept 1971. LP: EMI Reflexe IC 063-30 106. Reissued 1989 CD: CDM 7 63142 2. PN.

1973 Guillaume de Machaut, Chansons II. SdFM. LP: EMI Reflexe IC 063-30 109. Reissued 1990 CD: EMI Reflexe CDM 7 63424 2. PN.

1974 Estampie: Instrumentale Musik des Mittelalters.

Dances from British Library Add. Ms. 29987. SdFM, SCB. LP: EMI Reflexe

1C 063-30 122. PN. Reissued 1984? LP: His Master's Voice 1C 065 1301221.

1975 Musik der Spielleute = Music of the Minstrels. SdFM+. LP: Telefunken Das Alte Werk 6.41928 AW. Reissued 1985 LP: Musical Heritage Society MHS 7212.

1976 L'agonie du Languedoc. Brenton, Cardenal, Figueira, Sicart, Tomier

& Palazi. SdFM+; CM, chanteur. LP: EMI Reflexe IC 063-30 132. PN.

1976 Vox Humana: Vokalmusik aus dem Mittelalter.

anon., Daniel, Perotin, Petrus de Cruce, Raimbaut d'Aurenga, Meister

Alexander. SdFM+. Recorded 24 May-2 June 1976. LP: EMI Reflexe IC 069-46

401. Reissued 1989 CD: EMI Reflexe CDM 7 63148 S. PN.

1976 Carmina Burana: 33 Lieder aus der Original Handschrift circa 1300. SdFM, MM. 2 LP: Telefunken Das Alte Werk 6.35319. Reissue of Carmina Burana and Carmina Burana II. Also reissued 1987 2 CD: Teldec Das Alte Werk Reference 8.43775 ZS.

1978 Musik des Mittelalters. SdFM. 4 LP: Telefunken Das Alte Werk 6.35412. Composite reissue of Chansons der Troubadours, Chansons der Trouvères, Musik der Minnesänger, and Musik der Spielleute. Also reissued 1986 as Music of the Middle Ages. 4 Cass: Musical Heritage Society MI-IC 249442T (MHC 9442-9445); 4 LP: MUS 847442W (MHS 9442-9445).

1980 Cantigas de Santa Maria. MSCB+. LP: Deutsche Harmonia Mundi IC 069-99 898. Reissued 1992 CD: Deutsche Harmonia Mundi GD77242.

1981 Troubadours & Trouvères. SdFM. LP: Telefunken Das Alte Werk 6.35519. Composite reissue of Chansons der Troubadours and Chansons der Trouvères. PN. Also 1985? CD: Teldec Das Alte Werk 8.35519.

1982 Minnesänger und Spielleute. SdFM. 2 LP: Telefunken Das Alte Werk 6.35618. PN. Composite reissue of Minnesang und Spruchdichtung um 1200-1300 and Musik der Spielleute. Also reissued 1988 CD: Teldec Das Alte Werk 8.44105.

1984 The Greater Passion Play from Carmina Burana. IUEMI. 2 LP: Focus 831. Reissued 1990 CD: Musical Heritage Society MRS 522539; Cass: MHC 322539Y.

1984 Das grosse Passionsspiel aus der Handschrift Carmina Burana (13. Jahrhundert).

MSd3. Recorded 28-30 Mar 1983. 2 EP: Deutsche Harmonia Mundi Documenta 1C 164 16-9507-3. PN.

1988 Guillaume Dufay, Missa Se la lime ay pale: A Complete Nuptial Mass. IUPOS. Recorded 10 Oct 1987. Cass: Focus 882. 1993 CD: Focus 934.

1991 Hildegard of Bingen, The Lauds of Saint Ursula. IUEMI. Recorded 4 Feb 1991. CD: Focus 911.

1991 Laude. ILIEMI. Recorded 9-10 June 1988. CD: Focus 912.

1991 Adam dc la Halle, Le jeu de Robin et Marion. SCB. Recorded May 1987. CD: Focus 913.

1994 Guillaume Dufay, Missa Ecca Ancilla Domini. IUPOS. Recorded Dec 1991, Nov 1992, Nov 1993, June 1994. CD: Focus 941.

1994 Beyond Plainsong: Tropes and Polyphony in the Medieval Church. IUPOS. Recorded 6 Mar 1994. CD: Focus 943.

Key to Abbreviations:

Cass — cassette

CD — compact disc

CM — Claude Marti

CMW — Concentus Musicus Wien

cond. — conductor

dir. — director

EP e — extended play record (45 rpm)

EvGD — Ensemble vocale Guillaume Dufay

IUBO — Indiana University Baroque Orchestra

IUEM — Indiana University Early Music Institute

IUOT — Indiana University Opera Theater

IUPOS — Indiana University Pro Arte Singers

JB — Jean Bolery, speaker

JP — Joaquim Proubasta

LP — long-playing record

MM — Münchener Marienknaben

MSCB — Mittelalterensemblc der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis

MSCB+ — Mittelalterensemble der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis augmented by singers and/or instrumentalists

PN I — Includes program notes by TB

SCB — Schola Cantorum Basiliensis

SdFM — Studio der Frühen Musik

SdFM+ — Studio der Frühen Musik augmented by singers and/or instrumentalists

TB — Thomas Binkley

UICM — University of Illinois Collegium Musicum

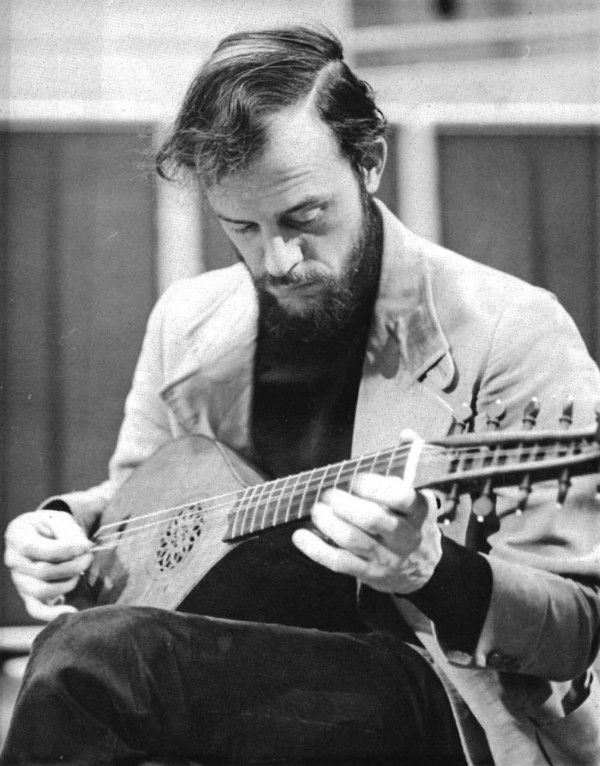

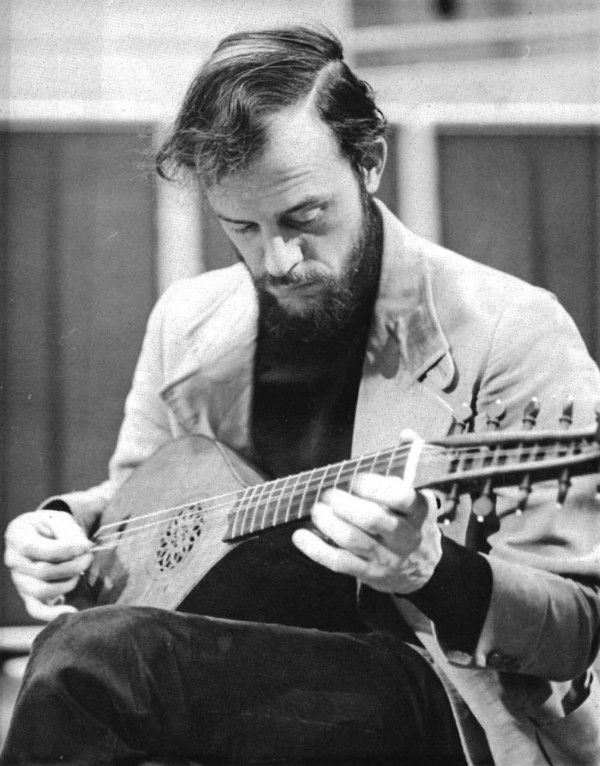

Photos, from top:

Tom Binkley with chitarra saracenica, 1965. Photo courtesy of Raglind Binkley.

Paris, mid to late 1960s. Studio der Frühen

Musik (from left to right: Sterling Jones, Andrea von Ramm, Willard

Cobb, Tom Binkley). Photo courtesy of Archives Lipnitzki, Paris.

At the Binkley property near Cobb, California, 1978. Tom and Raglind

Binkley with daughters Leonor, 4, and Isabel, 2. Photo by Harlan Hokin.

Last Week at Marienbad? Tom with lute, mood surrealistic, setting unknown.

Munich, 1970s. Tom rehearses for Pop Ago. © Photo K.I.P.P.A., Amsterdam.