Ondas — Martín Codax. Cantigas de Amigo

Vivabiancaluna Biffi, Pierre Hamon

outhere/arcana A 390

2015

1. Quand’eu vejo las ondas (cantiga de amor) [1:49]

text: Rui Fernandes de Santiago – music: Vivabiancaluna Biffi | Sources: B 903, V 488

2. Prelude [4:56]

on the theme of “Ondas do mar de Vigo”

ca I

with Pierre Hamon: frestel

3. Ondas do mar de Vigo (cantiga de amigo I) [5:06]

ca I

text & music: Martín Codax | Sources: B 1278, V 884, N 1

4. First reflection [3:12]

on the theme of “Quand’eu vejo las ondas”

5. Mandad’ei comigo (cantiga de amigo II) [5:36]

ca II

text & music: Martín Codax | Sources: B 1279, V 885, N 2

6. Mia irmana fremosa, treides comigo (cantiga de amigo III) [5:39]

ca III

text & music: Martín Codax | Sources: B 1280, V 886, N 3

7. Second reflection [1:54]

on the theme of “Quand’eu vejo las ondas”

Pierre Hamon: medieval double recorder

8. Interlude [2:07]

on the theme of “Quantas sabedes amar amigo”

ca V

9. Ai Deus, se sab’ora meu amigo (cantiga de amigo IV) [3:34]

ca IV

text & music: Martín Codax | Sources: B 1281, V 887, N 4

10. Interlude [2:24]

on the theme of “Ondas do mar de Vigo”

ca I

with Pierre Hamon: shevi

11. Quantas sabedes amar amigo (cantiga de amigo V) [2:48]

ca V

text & music: Martín Codax | Sources: B 1282, V 888, N 5

12. Eno sagrado, en Vigo (cantiga de amigo VI) [3:24]

ca VI

text: Martín Codax – music: Vivabiancaluna Biffi | Sources: B 1283, V 889, N 6

with Pierre Hamon: three holes recorders

13. Third reflection [1:17]

on the theme of “Quand’eu vejo las ondas”

14. Ai ondas que eu vin veer (cantiga de amigo VII) [2:13]

ca VII

text & music: Martín Codax | Sources: B 1284, V 890, N 7

with Pierre Hamon: medieval double recorder

15. Ũa dona que eu quero gram bem (cantiga de amor) [3:00]

text: Paio Gomes Charinho – music: improvisation on the theme of “Ondas do mar de Vigo”

ca I

Sources: B 810, V 394 — with Pierre Hamon: frestel

VIVABIANCALUNA BIFFI — voice and viola d’arco

www.vivabiancaluna.com

PIERRE HAMON — medieval flutes

www.pierrehamon.com

Viola d’arco Richard Earle, Basilea (Ch) 1997

– Bows Marco Casiraghi, Merate (It) 2010

– Strings Aquila Corde Armoniche (Vicenza - It), Damian Dlugolecki (Troutdale - USA)

Frestel (Medieval pan pipe) Jeff Barbe, Saint-André-Lachamp 2011

Three holes recorders Jeff Barbe, Saint-André-Lachamp

Shevi (Armenian shepherd’s flute) Karen Mukaekyan, Armenia 2013

Medieval double recorder Francesco Li Virghi, Orte (It) 2010

Medieval transverse flute Harsch Wardhan, Dehli 2001

℗2015 / ©2015 Outhere Music France.

Recorded at the Paradyż Abbey, Gościkowo (Poland), 8-11 September 2014 and at the Notre-Dame de Bon Secours,

Paris, 19 June 2015.

Artistic direction, recording, editing and mastering: Alban Moraud.

Produced by Outhere.

Sources:

B: Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Nacional – Lisboa, Biblioteca Nacional

V: Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Vaticana – Roma, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana [Vat. Lat. 4803]

N: Pergaminho Vindel – New York, Pierpont Morgan Library [ms. M979]

Total time 49:08

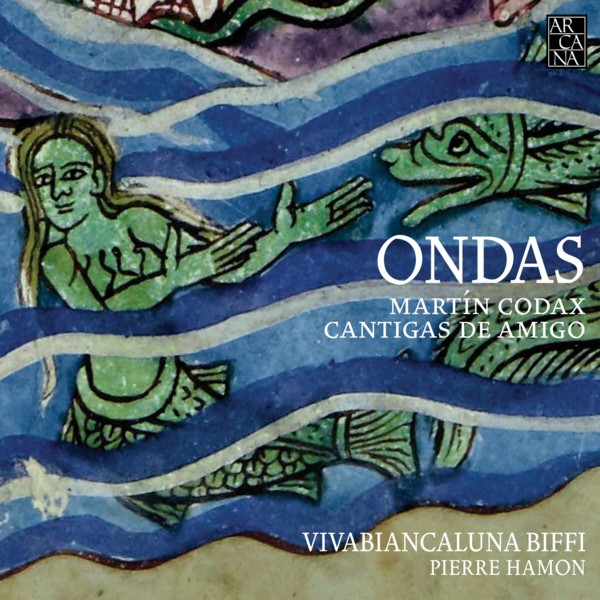

ICONOGRAPHY (DIGIPACK)

FRONT COVER AND INSIDE: Beatus of Liébana, Codex of the Monastery of San Andrés de Arroyo,

c. 1248, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Nouv. acq.

lat. 2290, f. 14r. © Bibliothèque nationale de France

ICONOGRAPHY (BOOKLET)

Page 16: VivaBiancaLuna Biffi – Paderno d’Adda, August 2007. ©Salvatore Cortese

TRANSLATIONS

ENGLISH: Irena Hill (irena@imogenforst erassociates.co.uk)

FRENCH: Carine Toucand (www.novaug.co.uk)

Sung texts

ENGLISH: Daniel L. Newman and Irena Hill (track s 1 & 15)

FRENCH: Manuel Lopes Pereira and Caroline Magalhâes (track s 1 & 15)

ITALIAN: Anna Laura Perugini and VivaBiancaLuna Biffi (track s 1 & 15)

EDITING: Donatella Buratti

GRAPHIC DESIGN: Mirco Milani

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As with Fermate il Passo, my previous CD, for Ondas

I should also name many extraordinary men and women who accompany me in

my musical and emotional life. This time I shall try to be brief, not

because there are fewer people to acknowledge, but because there are too

many, and to leave out even a single one would be a great pity. I shall

limit myself to mentioning the man who has made and is making this

recording adventure possible: Cezary Zych , with his passion and energy,

and all his wonderful staff who have worked with him for so long. And a

special thankyou to Anna Laura Perugini for allowing us to publish an

excerpt from her superb essay “La donna e il mare” [Women and the Sea],

part of her doctoral dissertation (Università degli studi della Tuscia,

Viterbo, 2001). And another thanks goes to the label Music Ficta which

allowed us to use translations of the Cantigas de Amigo by Martín Codax.

And

finally, in spite of everything, I thank those feelings of distant

longing, those days filled with sorrow – which we have all experienced

through loving – that gaping void which only the absence of those we

truly love can leave in our hearts and our souls. Without all these,

what would we be singing about?

ARCANA is a label of OUTHERE MUSIC FRANCE

31, rue du Faubourg Poissonnière — 75009 Paris

www.outhere-music.com www.facebook.com/OuthereMusic

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Giovanni Sgaria

MARTIN CODAX AND THE PERGAMINHO VINDEL

O God, if only my friend knew

How lonely I am in Vigo

And so much in love...

Oh, God, if only my beloved knew

How alone I am at Vigo!

And so much in love...

This

lament by a Galician woman, in which love and loneliness merge in a

magnificent and poignant crescendo, is the work of Martín Codax, an

early minstrel of Galician-Portuguese heritage, whose musical sense and

sensitivity are remarkable.

His cantigas appear, among those by many other composers, in two manuscripts, known today as the Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Nacional and the Cancioneiro da Vaticana.

These two important collections of Galician-Portuguese songs were

copied in Italy, presumably from earlier manuscripts, at the behest of

the humanist scholar Angelo Colocci in 1525-1526. The first was acquired

by the Portuguese government in 1924, and is now held by Lisbon’s

Biblioteca Nacional. The second is still in Rome’s Biblioteca Apostolica

Vaticana.

The most important document, however, was only

discovered in 1914, when the librarian Pedro Vindel, happened to unfold a

sheet of parchment that covered a fourteenth century manuscript of

Cicero’s De officiis and found inside it an even older codex, dating back to the 1200s, which contained some short cantigas.

The text itself attributed them to Martín Codax. Not only was this a

individually authored codex – a rare occurrence in Romance poetry – but

the verses were accompanied by a musical score for six arias, or modilhas.

The huge importance of this document, which became immediately known as Pergaminho Vindel,

cannot be overestimated. It contains the only known secular lyrics of

Galician-Portuguese poetry, accompanied by musical score – apart from

the Cantigas de Santa Maria, composed for Alfonso X of

Castile (1252-1284), which, however, are religious in content.

Unfortunately,

the little we know about Martín Codax is limited to what we can gather

from his songs. He is likely to have been a minstrel (jogral),

active around the middle of the thirteenth century, during the reign of

Afonso III of Portugal (1245-1279). This was a moment of great

creativity in Galician literature, which was in its turn part of the

widespread troubadour movement, a movement that was redrawing the

European cultural map. We can only glean Codax’s Galician origins from

the fact that his cantigas are centred on the town of Vigo,

possibly his birthplace, of which he mentions the bay, facing the

Atlantic, and the church, where amorous assignations take place.

Formal considerations

Codax’s seven cantigas

are rather compact, from the viewpoint of both theme and metric

structure. They belong to the typically Galician genre known as cantigas de amigo,

in which a woman addresses a man, and the love story they depict is

characterised by distant longing and feelings of loneliness. The voice

of a young woman addresses the ocean waves, or God, expressing her

disquiet at the lack of news of her friend; or she addresses her mother,

her sister and her women friends, speaking of her plans to meet him.

This is the theme of the coita d’amor, the pain and sorrow for a

faraway, unreachable lover, one who has possibly been lost forever. And

the slow rhythm of the waves in Vigo amplifies and transfigures this

wistful melancholy:

Waves of Vigo Bay,

Have you seen my friend?

O God! Will I see him soon?

Waves of a vile sea,

Have you seen my beloved O God!

Will I see him soon?

The structure is typical of the cantigas de amigo: verses of two lines, followed by a third as refrain, or refrão.

The parallel pattern is very clear: thematic variety is sacrificed in

favour of the obsessive repetition of the same motif. And yet, precisely

because the language is reduced to a minimum, the constant variations

and the repetition of the verses produce a remarkable compositional

musicality. The expressive nucleus, declared in its entirety from the

very first line, does not allow for any change or development. The

situation is fixed and all encompassing – in this case it is centred on

the sadness of the woman who stares at the sea while awaiting the return

of her beloved.

Of the seven songs in the Pergaminho Vindel,

six are accompanied by musical notations; oddly, the remaining one

(number VI) is accompanied by an empty pentagram. The text of this cantiga

is markedly different from the others. In this case, a narrator

describes the dance performed by a woman during a religious festival in

Vigo.

In a sanctuary in Vigo,

A gracious body was dancing.

My love...

In Vigo, in a sanctuary,

A svelte body was dancing.

My love...

The sea as a constant presence

The tormented love and the longing depicted in the seven cantigas suggest images of great sensuality. We find clues of this above all in the refrãos, but also, for instance, in the idea of the woman in love bathing in those waves, which seem to symbolise the unconscious.

Come with me to Vigo Bay

And we shall see my friend:

And we shall swim in the waves!

Come with me to the stormy sea

And we shall see my beloved:

And we shall swim in the waves!

The sea, in all its manifestations, is the recurring leitmotif of the Galician-Portuguese cantigas, but Martín Codax seems to have a special predilection for it. Of the seven songs in the Pergaminho Vindel, four contain explicit references to the sea.

It

might seem to be stating the obvious to mention the close relationship

between Portugal and the factor that more than any other has influenced

its history and culture: the Atlantic Ocean. All of this country’s major

achievements have involved exploration, and it is not by chance that

its literature reached its apex with the epic of the Lusíadas.

Nevertheless,

the sea of Luis de Camóes bears no resemblance to that of Martín Codax.

The two are separated not only by three centuries of history, but by a

whole world view. The oceans sung by Camóes are, in fact, the ones that

the adventurous Portuguese seafarers were on the brink of conquering. In

Codax’s day, on the other hand, before Columbus and Vasco de Gama set

out on their voyages, Portugal was the last frontier of the known world,

the farthest piece of land before the river Ōkeanós, the origin and end of all things.

There

is, therefore, an unsettling symbolic meaning in this infinite sea that

opens out beyond the bay of Vigo: the woman who is lamenting the fact

that her beloved is so far away is in fact looking into the void, into

the next world.

Cultural context

Before the moment at which the cantigas de amigo and de amor

appeared, love had been represented as the opposition between divine

and spiritual love on one side, and lust and carnal love on the other.

But then, going beyond the religious tradition, what became crucial was

the viewpoint of the individual. In Provence, troubadours ‘invent’ a

third kind of love, that of a man for a woman, whose goal is neither

marriage nor carnal intercourse: it is the kind of love which is still

capable of raising and sublimating the human spirit. It is fin’amor,

‘courtly love.’

The poetry of the troubadours soon spread outside Provence, inspiring the Minnesänger

in Germany and the ‘stil novo’ artists in Italy; in the Iberian

peninsula it spurred the blossoming of the Galician-Portuguese sung

poems. We don’t know for certain of any eminent Provençal troubadours

living at the Portuguese court, but the rapid spread into Galicia of

this type of poetry can be sufficiently explained by that region’s close

ties with France. The fervour of the pilgrimages to Compostela fostered

rich interactions between troubadours from Occitaine and the indigenous

poetic tradition.

When transplanted to the Atlantic coast, the

various troubadour genres were not simply imitated, but were also

reinterpreted in keeping with local sensibilities. The cantigas de amor differ from their Provençal counterparts: the fin’amor

is replaced by a more realistic and concrete form, objective, and very

close to biographical facts; the Galician-Portuguese poets replace the

Provençal joi with a love notably devoid of that joy that for the

Provençals was ever present, in the name of an existential fullness. In

contrast, in the local cantigas love is seen as the illusion of a soul

that knows from the start it is doomed to be defeated; for the

Galician-Portuguese, the eyes, which for Guiraut de Borneilh were the

bridge across which love reaches the heart, are the vehicle for both the

pleasure of contemplation and for the curse and the inevitability of

unhappiness.

The originality of the Cantigas de Amigo

It is in the cantigas de amigo that the Galician-Portuguese songs develop their most original features.

The most important characteristic of the cantigas de amigo, as opposed to the cantigas de amor, is that they are true chansons de femme: for the first time, it is the female voice that expresses passion and the pains of love.

Beautiful, atmospheric and infinitely delicate, the songs of Martín Codax remain among the best examples of cantigas de amigo.

Influenced by the poetry of the troubadours, infused with Christian,

Arab and Celtic symbolism, distilled by the hand of an unusually

sensitive artist, they none the less belong to the Galician-Portuguese

world, and totally so.

Even today, the desperately sad fado,

the Portuguese national song-form, maintains the rhythm of waves and

tides, and feels like the lament of a woman who looks out to sea and

wonders when her beloved will return to her.

ANNA LAURA PERUGINI

About the composers

Rui Fernandes de Santiago

Galician

troubadour and cleric, active around the middle of the thirteenth

century, most likely at the court of Alfonso X of Castile, know as El Sabio (The Wise).

Martín Codax

Very little is known about Martín Codax: he was probably a minstrel (jogral)

from the town of Vigo, and active around the middle of the thirteenth

century during the reign of Alfonso III of Portugal, known as The Restorer.

Paio Gomes Charinho

Galician troubadour, active in the last decade of the thirteenth century at the court of Sancho IV of Castile, known as El Bravo (The Bold). He was buried in the Convent of Saint Francis in Pontevedra (Galicia).

INTERPRETATIVE NOTES

“Ondas”

is part of a process that started long ago. Ever since I became

involved in ancient music, twenty years ago, I have been experimenting

with singing accompanied by a viola d’arco – not so much wishing to

create a novel way of performing as simply out of curiosity about

combining two melodic lines and being able to listen to them together

straight away. The result of this earlier exploration developed into “Fermate il Passo”, a programme for live performance and CD, devoted to the repertoire of the Frottole of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. In “Ondas”

I decided to take on the challenge of monody. At the start of my

adventure in mediaeval music, as an enthusiastic but ignorant student, I

believed that monodic music was too simple and not very interesting: a

single melodic line, the accompaniment to be imagined, often limited to a

single drone, verses in obscure languages. Today, with the experience

of many years and the good fortune of having met many experts in the art

of monody, I understand that, precisely because of this pared-down

quality, it forms one of the most complex repertoires a performer can

take on, both as a singer and as an accompanist. These cantigas

captivated me first of all through their words: the loneliness of love

vis-à-vis, the immensity of the ocean, and all the emotions this

engenders. The seven cantigas de amigo

by Martín Codax, where it is the female voice that sings of

longing and hope in a dialogue with the waves, are set between two cantigas de amor, where it is a man who speaks, seeing the ocean as a painful reminder of lost love.

As

always, it is important for me to say that my interpretation of the

various repertoires does not pretend to offer the ultimate musicological

answer: what I put forward is one hypothesis among many others, and I

humbly reserve the right to change my mind in the future, in the light

of new experiences, new study, knowledge and encounters.

Last but

not least. A great musician, but above all a dear friend and a

wonderful person: Pierre Hamon honours me with his human and artistic

presence in this programme dedicated to the ocean’s waves.

VIVABIANCALUNA BIFFI

The flutes

The

flutes used in this recording are reproductions of instruments whose

existence in the thirteenth century is fully documented: the mediaeval

pan pipes, or “frestel”, an ancient instrument used for purposes of

communication and still in use today by the itinerant knife-grinders of

Galicia and Portugal; the transverse flute, depicted in the

illuminations of the Cantigas de Santa Maria; the double

recorders, both as two separate three-hole recorders and as an

instrument in its own right, and the simple shepherd’s reeded flute.

However, what led us to choose these instruments, and in particular the

mediaeval pan pipes, is their capacity to evoke, at an unconscious

level, the sea, the waves, the rolling of wind and sand... the “Ondas do Mar”.

PIERRE HAMON