Epos. Musica dell'era carolingia

Cantilena Antiqua

medieval.org

cantilenantiqua.com

Passacaille PAS 974

2011

grabación: Volmare Are Studio, Bologna

marzo de 2009

Anicius Manlius Torquatus Severinus Boethius

De Philosophia consolatione

01 - Bella bis quinis [6:16]

Godescalcus

de Orbais · Paris Lat. 1154

02 - Ut quid iubes pusiole [7:04]

Publius Vergilius Maro

03 - Aeneis Liber II [8:20]

v. 42-50; v. 274-279; 281-287

anonimus, Paris Lat. 1154

04 - Planctus Karoli [6:52]

05 - Hug dulce nomen [7:15]

Anicius Manlius Torquatus Severinus Boethius

De Philosophia consolatione

06 - O stelliferi conditor orbis [9:39]

Quintus Horatius

Flaccus

Epistula I, 4

07 - Albi ne doleas [3:23]

Publius Vergilius Maro

08 - Aeneis Liber IV [8:32]

v. 424-437; v. 651-658

Quintus Horatius

Flaccus

carmina Liber IV ode XI

09 - Est mihi nonum [3:49]

Angilbertus · Paris Lat. 1154

10 - Aurora cum primo mane [8:50]

musica: anonimus

Ensemble Cantilena Antiqua

Stefano Albarello

Stefano Albarello: cantus, lyra, cithara

Paolo Faldi: tibiae

Gianfranco Russo: fidula

Marco Muzzati: tintinnabula, psalterium, cimbala

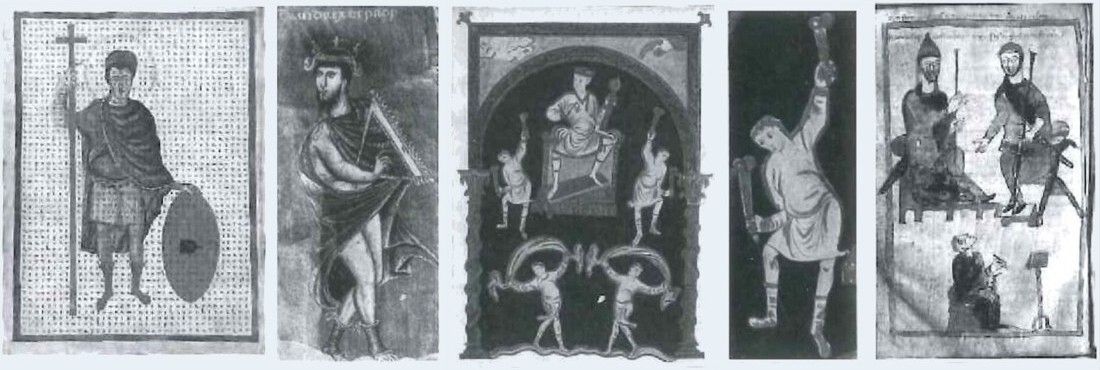

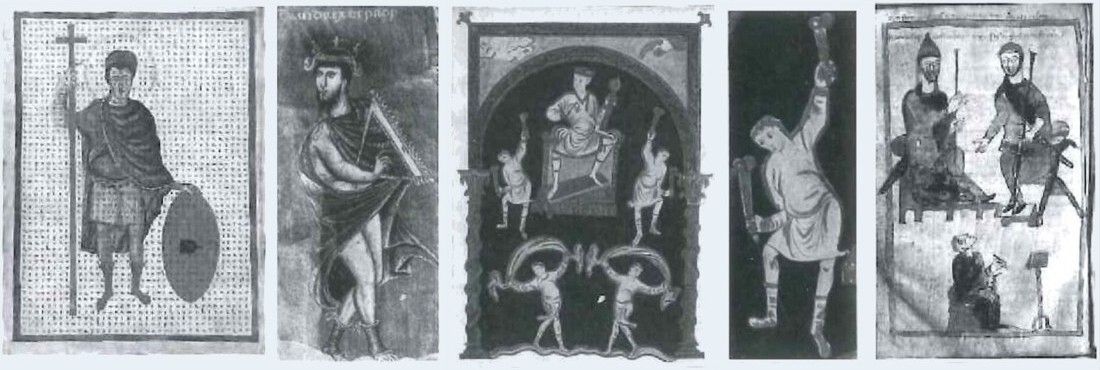

The Carolingian era marks an important moment in the history of early

medieval Latin lyrical poetry and medieval music. The Carolingian

revival was fundamental to the rehabilitation of the classical

tradition, which had been neglected during a barbarous period, as it

combined elements from the classical and patristic traditions to lay

the foundations of a new culture. This rediscovery of Latin classicism

by way of the Hellenic culture blended major contributions from the

Byzantine and Oriental cultures with those of the Anglo-Celtic world,

from which came notably Alcuin of York, who reorganised the Church; but

it also integrated important contributions of intellectuals from the

Mediterrenean area such as Teodulf, Paulinus of Aquileia and the

Lombard Paul the Deacon.

The results of this revival are apparently all represented in the

manuscript Lat. 1154, now in Paris, which can be considered a

testamentary compilation of the Carolingian culture. It was written

around the end of the ninth and the beginning of the tenth century. In

this manuscript are preserved, among many others, a series of

compositions which report historical facts about this dynasty,

represent an important epic and elegiac heritage from before the year

one thousand. We found it quite extraordinary that some of these poems

are linked to a musical score (typical Aquitanian neumes). Even if it

is only a small one, this collection of cantos represents an important

'repertoire' from that time; it includes moral, epic and convivial

writings even by classical authors such as Horace, Virgil and Boethius.

It is hardly surprising that the Carolingian dynasty should have

furthered the revaluation of the latter philosopher and his work, above

all the 'De philosophiae consolatione', from which the verses

of two of the compositions recorded here are drawn.

A truly remarkable event has been the discovery in a manuscript of the

Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence of various fragments of the Aeneid

linked to musical notation; they are precious evidence of the

practice of singing the verses of this monumental work.

With regard to the contemporary poets, we come across Gottschalk of

Orbais, a theologian and poet born in Saxony. He entered the monastery

of Fulda, under abbot Rabanus Maurus, who had been educated at the

school of Alcuin. However, disgraced after being accused of heresy,

Gottschalk was expelled from the monastery and exiled. In in his song

(Ut quid iubes pustole) he clearly expresses his deep distress about

the exile, with perhaps a dedication to his friend Walfridus Strabo.

Another writer in this anthology is Angilbert, of Frankish stock, who

was educated at Charlemagre's court, where he met Alcuin and Paulinus

of Aquileia. He proved to be an excellent diplomat, and was sent by

Charlemagne as an emissary to the Pope.

He had two children with Bertha, the daughter of Charlemagne, who

protected this illegitimate relationship. Perhaps because of Alcuin's

insistent disapproval, Angilbert eventually renounced worldly life and

went on to become a Lay Abbot at Saint-Riquier. While at Charlemagne's

court, Angilbert was so successful as a poet that he was given the

nickname of Homer. The poem The Battle of Fontenoy is

attributed to him (in one verse he names himself as the author), and

some also assign the 'Planctus de obitu Karoli' (Lament on the

Death of Charlemagne) to him , but this last is controversial, as the

author may also be an anonymous Italian poet, perhaps from Bobbio,

given that one of the last stanzas mentions the deeply venerated Saint

Columban, who had founded an important monastery, precisely in Bobbio.

It also has to be stressed that the Planctus Karoli of Lat.

1154 follows an arrangement of verses and melody that differs from

that of the other poems with a hymnic musical structure, and in which

the A melody is dedicated to the lines of the first two

stanzas, and the B melody, to those of the following stanzas.

As to the lines which in other sources always alternate with the

inserted line 'heu mihi misero', they alternate in our

manuscript with the A melody rendering the line 'heu dolens

plango', which generates a more complex and fuller structure.

Moreover, compared to the other sources, the original text is reduced

by many lines.

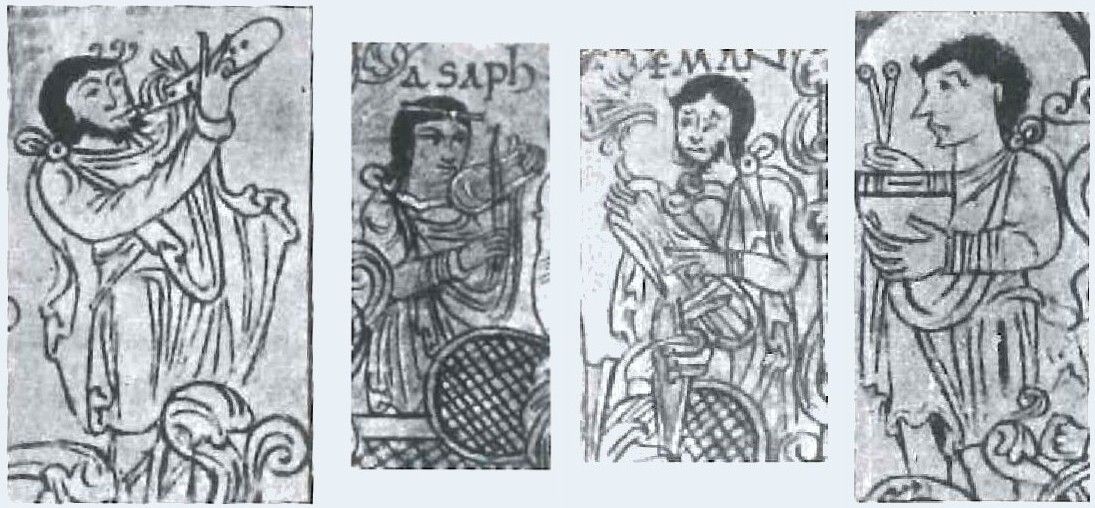

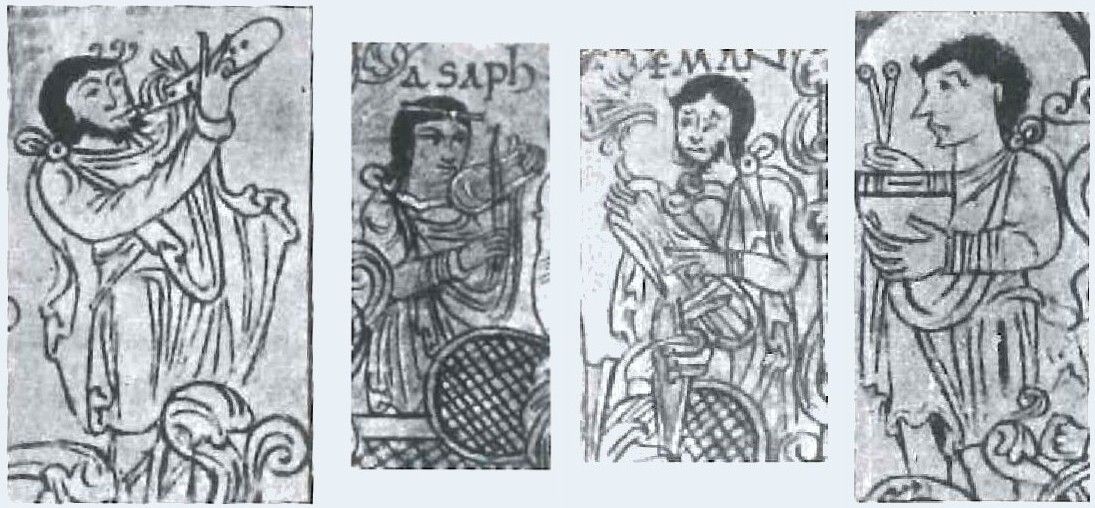

In general it must be said that these are not purely musical

manuscripts, the notation clearly being a later addition to the

literary texts. This gives rise to questions about the normal practice

and performance possibilities of these poems (maybe simple exercises in

style?). The notation is mostly (in our opinion) an attempt at

diastematic writing in Ms. Lat. 1154, while the Aeneid

still follows the linear adiastematic tradition. We believe that this

illustrates the stage of experimentation and development musical

writing was going through at the time. We therefore considered it to be

possible to reinterpret these melodies, providing we followed a

methodology in accordance with the rules of the time. Even the

instrumentation is dictated by the organological and archeological

sources. As a matter of priority it was necessary to reconstruct the

lyra on the basis of the models found in Germany and England or of the

cythara of Roman tradition. These are all instruments referred to by

the eminent music theorist of the time, Hucbald, and also mentioned in

contemporary songs (such as 'lam dulcis amica venito' and 'Aurea

personet lyra').

2009 © Stefano Albarello

Translation: Chris Cartwrigt