Nicholas LUDFORD / The Cardinall's Musick

Missa Videte miraculum · Ave cuius conceptio

medieval.org

AS&V Gaudeamus 131

1993

MISSA VIDETE MIRACULUM

with Plainsong Propers for the Feast of the Purification

01 - Introitus. Suscepimus Deus [4:39]

02 - Kyrie. Deus creator omnium [2:22]

03 - GLORIA [10:15]

04 - Gradualis. Suscepimus Deus [2:22]

05 - Alleluya. Adorabo ad templum [1:41]

06 - Sequencia. Hac clara [2:29]

07 - CREDO [11:21]

08 - Offertorium. Diffusa est gratia [1:45]

09 - SANCTUS · BENEDICTUS [10:43]

10 - AGNUS DEI [6:49]

11 - Communio. Responsa accepit Symeon [0:58]

12 - AVE CUIUS CONCEPTIO [9:23]

13 - Responsorium. Videte miraculum [4:34]

THE CARDINALL'S MUSICK

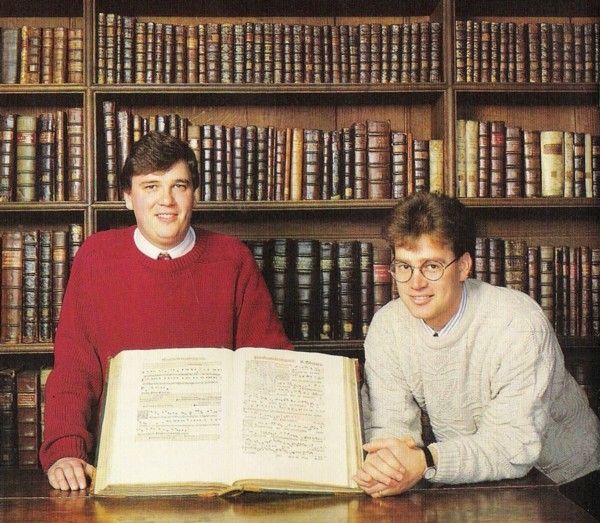

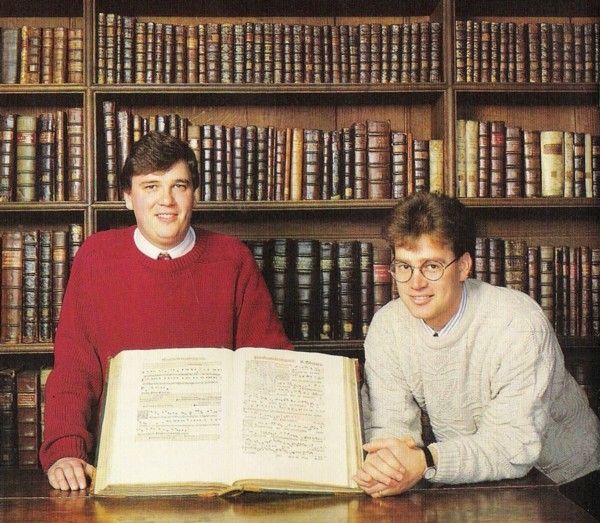

Andrew Carwood, David Skinner

Sopranos: Carys Lane, Caroline Ashton, Juliet Schiemann, Fiona

Clark, Olive Simpson, Rebecca Outram

Altos: David Gould, Nigel Short, Stephen Taylor

Tenors: Paul Badley, Philip Cave, Simon Berridge, David Jones,

Tom Phillips, Matthew Vine

Baritones: Paul Charrier, Robert Evans, Edward Wickham

Basses: Bruce Hamilton, Robert Macdonald, Michael McCarthy

Producer: David Skinner

Recording Engineer: Martin Haskell

Recorded in: All Saint's Church, Petersham

Design: Studio B, The Creative People

Cover: Vittore Carpaccio (c. 1460/5-1523/6) "Presentation of Mary in

the Temple", Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan/Bridgeman Art Library, London

Photograph: Stuart Bebb

THE WORKS OF NICHOLAS LUDFORD

Volume I

The name of Nicholas Ludford is familiar to most students of English

music. He is generally perceived as a lesser contemporary of Robert

Fayrfax (Ludford's festal masses are preserved with those by Fayrfax in

the great early 16th-century choirbooks at Lambeth Palace, London, and

Caius College, Cambridge), and all that is commonly known of him is

that his music defines the gap between Fayrfax and John Taverner.

However, most are unaware that, with eleven complete and three

incomplete mass settings (with a record of another three which are now

lost), Ludford was the most prolific composer of masses in Tudor

England. He possessed compositional skills equal to any of his

better-known contemporaries, and was indeed one of the greatest

composers for the pre-Reformation church in England. Although a

substantial amount of information concerning Ludford and his music has

circulated this century, until now his music has never been committed

to disc. John Caldwell, in his recently published Oxford History of

English Music, comments that it is "... more a matter of

astonishment that such mastery should be displayed by a composer of

whom virtually nothing was known until modern times". The present

ASV/Cardinall's Musick series will include Ludford's complete festal

masses, each set within its appropriate liturgical framework, and aims

to establish him as one of the last unsung geniuses of Tudor polyphony.

Nothing is known of Ludford's early career. His date of birth is

estimated to be 1485, an assumption which is drawn largely from his

entry into membership of the Fraternity of St Nicholas — a guild

of London parish clerks — in 1521 (Fayrfax was admitted in 1502,

and Taverner in 1514). From after the turn of the century Ludford

became attached to St Stephen's, Westminster, a college of secular

canons adjoining the Royal Palace of Westminster, where he remained

until its dissolution by Henry VIII in 1547. In the dissolution

certificate Ludford is named as 'verger' and was awarded a pension,

receiving payment as late as 1556. It is assumed that he died in 1557.

Forty years later, Thomas Morley mentions Ludford as one of the listed

'authorities' for his famous Introduction to Practical! Musicke

(London, 1597). However, Ludford's music was already forgotten by the

17th century and remained so for 300 years. In the present century two

movements occurred to resurrect Ludford and his music. In 1913, H.B.

Collins presented a paper at the Musical Association which briefly

outlines Ludford along with several other Tudor composers. In response

to Collins's paper, Sir Richard Terry announced the publication of

Ludford's complete masses (his several abridged editions of Ludford's

masses were already being performed by his choir at Westminster

Cathedral). Although Terry was never able to publish his works,

Ludford's name was firmly established in academic circles, and this led

to the compilation of his first biography by W.H.G. Flood in 1925.

Ludford then again fell silent for thirty years until a new wave of

academics attempted to reintroduce him and his music. In 1958 Hugh

Baillie substantially revised and corrected Ludford's biography and

outlined his musical development; a few years later John Bergsagel

fulfilled Terry's promise and published Ludford's complete masses, with

articles on his music. However, Ludford was again set aside and it is

curious that, in their well-founded exhilaration for his

contemporaries, most enthusiasts of Tudor polyphony have overlooked the

fine qualities of his music. With the market for 16th-century polyphony

ever increasing, it remains puzzling that such an extraordinary

musician as Ludford be disregarded for so long.

Reasons for this neglect may stem from the modest circumstances of his

life. Ludford was not well known in his own day and remained

politically and musically inconspicuous throughout his career; he

appears not to have taken a university degree and his name is not

recorded in conjunction with any major events. The few contemporary

references show him to be a retiring personality and deeply religious.

Whereas most composers who survived the English Reformation adapted

their styles to accommodate changing liturgical requirements (such as

Tallis and Sheppard), Ludford apparently stopped composing altogether

after about 1535. It is believed that this was due either to old age

and increasing infirmity or to the fact that his attachment to

Catholicism was such that he could not continue to produce music for

the reformed church.

Perhaps the most striking characteristic of Ludford's music is his

imaginative use of vocal texture, combined with a remarkable quantity,

and quality, of splendid melodies. Missa Videte miraculum, for

six voices, is unusually scored with two equal treble parts throughout.

The work derives its name from the cantus firmus upon which it

is based (Vespers respond, Purification); this migrates from one voice

to another at various points in each movement. The Agnus Dei is unusual

in that as a cantus firmus Ludford employs the respond verse

'Hec speciosum', although the head motif is identical to the other

movements. Ave suius conceptio, for five voices, is one of

Ludford's three votive antiphons which remain reconstructible (all lack

the tenor). A considerably later composition than the mass, its text

survives in numerous printed English prayer books from the early 16th

century. Fayrfax is also known to have set a work (now lost) on the

same text.

A great concern when familiarising oneself with a neglected composer

for the first time is whether or not the music warrants public revival.

Although, academically, some music may look impressive on paper, it is

sometimes the case that the same music in performance can be

disappointing. Ludford has had the sound backing of musicologists for

nearly 100 years, and now awaits the critical ear of the listener.

Perhaps the freshest opinion we can offer is that of the singers on

this recording — in simple yet resounding terms, his music is

"tuneful, electrifying, and memorable".

© 1993 David Skinner

SOURCES

Polyphony:

Missa Videte miraculum

Cambridge University Library, Gonville and Caius MS 667, p32.

Ave cuius conceptio

Cambridge University Library, Peterhouse MSS 471-74; ff. 93, 84v, 104,

80, (Baritone editorially supplied).

Plainsong:

Oxford, Christ Church Library, Graduate secundum morem et

consuetudinem preclare ecclesie Sarum politissimis formulis (ut res

ipsa indicat) in alma Parisiorum Academia impressum, (Paris, 1527).

Antiphonale Sarisburiensis, Partis Hyemalis, (Paris, 1519) f.

43v.

Music edited by David Skinner, and published by The Cardinall's Musick

(Edition)

THE FEAST OF THE PURIFICATION OF OUR LADY

Originally brought from the East by monks fleeing the Moslem invasion

of the Holy Land in the seventh century, the Purification celebrates

three elements described in chapter two of St Luke's Gospel (22-35).

Firstly, that Mary and Joseph, in order to conform to Jewish law as

laid down in Exodus, should present their first-born son to the Temple

to be dedicated to God; secondly, that having borne a child, the mother

was now unclean, disqualified from public worship and therefore in need

of purification through an offering; and thirdly the prophecies of

Simeon and Anna.

In the Eastern rites, the emphasis was on Christ's presentation,

fulfilling the prophecy contained in the Book of Malachi — "...

the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple" (3:1) —

and allowing the liturgy to reflect the story of Christ's life in

scriptural order. But the emphasis in the West was so centred around

the Virigin that it soon became a Marian feast celebrating her

purification, in spite of a major theological problem. Why was Mary

(who was free from original sin) in need of purification? The answer

was said to lie in Mary's piety and her humble acceptance of religious

law: as it says in Ludford's antiphon Ave cuius conceptio,

"cuius purificatio fuit purgatio" — her "purification was our

expiation".

Simeon's prophecy is enshrined in the Catholic office of Compline and

the Anglican office of Evensong as the Nunc dimittis. It

contains not only the joy of Simeon's fulfilment but also the important

truth that Christ's redemption is not just for the circumcised but for

all — "a light for revelation to the Gentiles" (Luke 2:32).

Simeon goes on to warn of the difficulties of Christ's life and the

piercing of Mary's heart by a sword.

In the main, the texts for the Mass concentrate on elements of the

Presentation. The Introit, Gradual, Alleluya and Communion are all

concerned with waiting for deliverance: the Communion specifically

speaks of Simeon. The Sequence and the Offertory have Mary as their

theme but make no attempt to deal with her purification, celebrating

rather her lack of sin and her importance as the body through which

redemption is made possible.

Liturgically, the feast falling forty days after the Nativity (forty

being a mystical number) is the final feast of the Christmas cycle. It

also has attached to it the title Candlemas which grows out of the

tradition of processing with candles during the singing of antiphons

before the Mass, symbolising Christ as the light of the world and

welcoming his redemption. In spite of a ban by the English Reformers in

1548, it remains a regular part of the Feast's celebrations

© 1993 Andrew Carwood