Robert FAYRFAX / The Cardinall's Musick

Missa O quam glorifica · Ave Dei patris filia

medieval.org

AS&V Gaudeamus 142

1995

Robert FAYRFAX

1464—1521

1. Kyrie. Orbis factor [1:46]

Missa O quam glorifica

2. Gloria [11:19]

3. Credo [12:25]

4. Sanctus · Benedictus [13:23]

5. Agnus Dei [10:23]

6. Hymnus. O quam glorifica [2:41]

7. Ave Dei patris filia [12:03]

8. Sumwhat musyng [3:47]

9. That was my joy [2:55]

anonymous

10. To complayne me, alas [3:45]

THE CARDINALL'S MUSICK

Andrew Carwood

Sopranos: Carys Lane, Rebecca Outram, Olive Simpson

Altos: Mark Chambers, Patrick Craig, Charles Humphries

Tenors: Robert Johnston, Julian Stocker, Matthew Vine

Baritones: Simon Davies, Robert Evans, Charles Pott

Basses: Jonathon Arnold, Robert Macdonald, Michael McCarthy

Sumwhat musying & To complayne me, alas:

Robin Blaze, Andrew Carwood, Robert Macdonald

That was my joy:

Andrew Carwood, Matthew Vine, Robert Macdonald

Producer: David Skinner

Recording Engineer: Martin Haskell

Recorded in: Fitzalan Chapel, Arundel Castle, Arundel, 23-24 November

1994

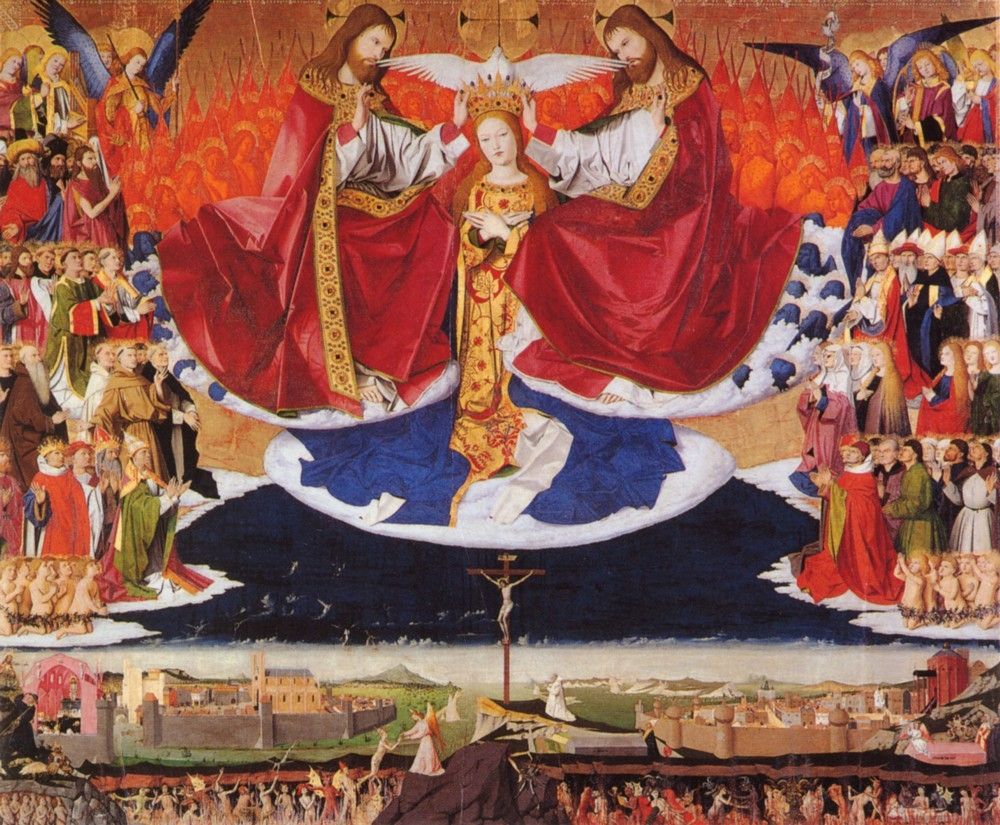

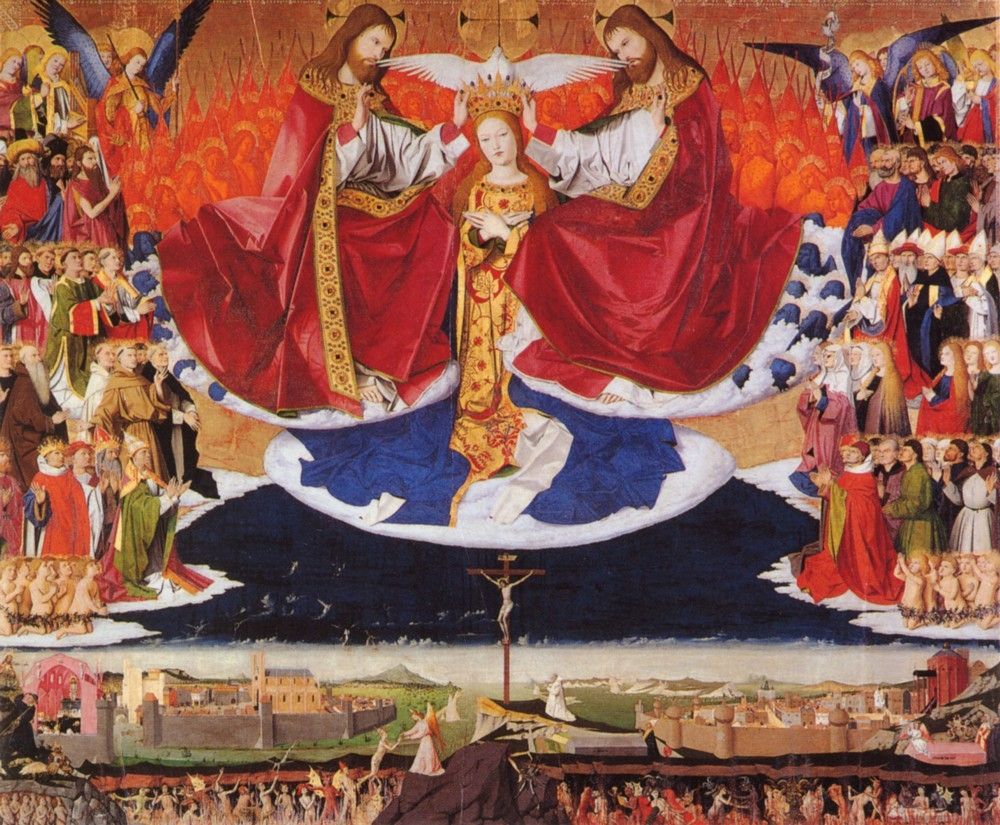

Front cover painting: The Coronation of the Virgin, by Enguerrand

Quarton (1410 - 66),

Villeneuve-Les-Avignon (Hospice), Anjou, courtesy of Giraudon /

Bridgeman Art Library

THE WORKS OF ROBERT FAYRFAX

VOLUME I

Writing more than 65 years ago Sir Richard Terry, a pioneering force in

the performance of Tudor church music, bemoaned that "our national

habit of self-depreciation has never been more curiously exhibited than

in our treatment of early British composers". One needs only to thumb

through a recent catalogue of recordings to see the extent of the

commitment modern performers have shown to England's rich musical

heritage. The same catalogue, however, also reveals that one of the

most inspiring periods in the development of English polyphony has yet

to be fully explored on record: namely the first few decades of the

sixteenth century when church music arrived at its most developed and

refined state. Other than a few key figures such as Taverner and

Sheppard, and certain composers represented in the Eton Choirbook, a

considerable measure of this magnificent music remains unheard. More

technical mastery of this age may now be sampled in the recent series

of music by Nicholas Ludford (ASV CD GAU 131, 132, 133, 140), and

further riches are still to be found in other relatively unknown

composers such as William Pasche, Thomas Ashwell, Edmund Stourton and

John Merbecke, whose works we will be investigating in due course. The

great Dr Robert Fayrfax stands at the head of all these men; he was

widely recognised as the most distinguished musician of his time, his

music continued to be copied into manuscripts more than a century after

his death and his ingenious compositional innovations served as a model

to the many famous names which followed him. This is the first issue of

a projected five-volume survey of Fayrfax's masses, votive antiphons

and secular songs, and hopes to generate a renewed interest in one of

England's most celebrated composers.

Robert Fayrfax was born in Deeping Gate, Lincolnshire, on 23 April

1464; nothing is yet known of his childhood or early musical training.

He became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal by 6 December 1497 when he

was granted a chaplaincy of the Free Chapel at Snodhill Castle, a post

which was relinquished a year later to Robert Cowper, a fellow

Gentleman. Fayrfax gained a Mus.B. from Cambridge in 1501, and a Mus.D.

in 1504; he later acquired a D.Mus. from Oxford (by incorporation) in

1511. As a singer he is first recorded in 1500 among the lay clerks at

the funeral of Prince Edmund, the third son of Henry VII; he was also

present at the funeral of Queen Elizabeth, wife of Henry VII, on 23

February 1503. Later lists place him at the head of the singing men at

the funeral of Henry VII (11 May 1509), the coronation of Henry VIII

(24 June 1509), the funeral of Prince Henry (27 February 1511), and the

great Anglo-French summit at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in the

summer of 1520. Henry VIII, who was somewhat of a skilled musician

himself, evidently admired Fayrfax's musical talents and granted the

composer numerous royal benefices during the last few decades of his

life. From 1509 he was awarded an annuity of £9 2s 6d

on top of his salary as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal and on 10

September 1514 he was appointed one of the poor knights of Windsor

Castle, receiving 12d a day for life. The king's New Year's Day

rewards between 1516 and 1520 also record that Fayrfax was paid

enormous sums of money for music manuscripts, some amounting to

£20.

From 1502 he may have been on the musical staff at St Alban's Abbey,

though it is not known in what capacity. It has been suggested that

Fayrfax was never likely to have been employed at St Alban's and

probably held some sort of honorary post there; however, as he composed

a mass and antiphon dedicated to St Alban and requested burial in the

Abbey, a more substantial connection would seem once to have existed.

Very little is known of Fayrfax's private life; a seventeenth-century

rubbing of the monument brass which once marked his tomb in St Alban's

Abbey reveals that he died on 24 October 1521 at the age of 57. He was

survived by his wife, Agnes, and an unknown number of children.

Fayrfax may have been a composer of some national repute by his

mid-thirties when a few of his compositions were copied into the Eton

Choirbook (c.1500); the Caius and Lambeth Choirbooks (assembled in the

mid to late 1520s) contain the earliest surviving collections of his

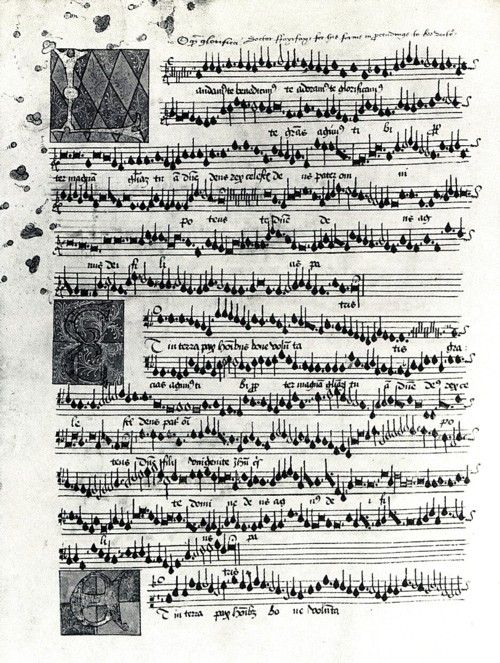

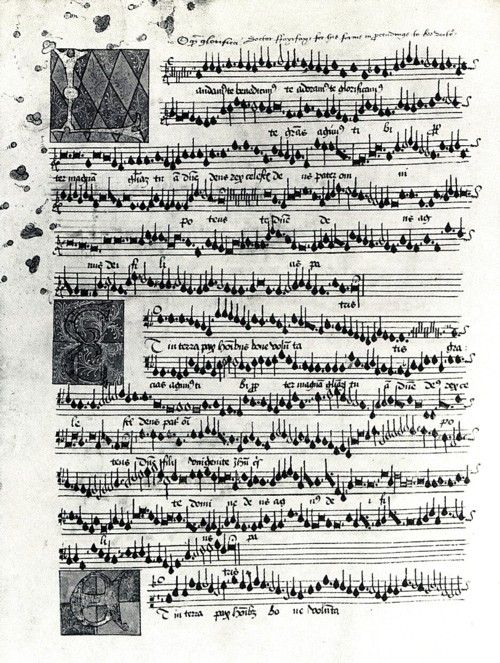

masses. Missa O quam glorifica is perhaps Fayrfax's most

complex if not most impressive work. According to an inscription in the

Lambeth Choirbook it was composed 'for his forme in proceading to bee

Doctor'; no doubt this was his exercise for Cambridge University in

1504, the earliest English example known to us. The standard

requirement for an early Tudor doctorate was the submission of a mass

and antiphon, which were to be performed on the day of taking the

degree (no antiphon of this type is known to have survived among

Fayrfax's output). A modern edition of Missa O quam glorifica

was prepared by E. B. Warren in 1959 (Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae,

17/1), although unfortunately it is afflicted with numerous printing

errors, awkward alignment, and inaccurate interpretation of triplet

rhythms, at several points.

The notation in the Caius and Lambeth Choirbooks is very clear and

logical, and presents few editorial problems. However, it is possible

that if the manuscript which Fayrfax submitted for his degree had

survived, the original notation might have been a challenge even for

the most proficient of late-Medieval lay clerks. A theory has been put

forward by Roger Bray that the versions of Fayrfax's Missa O quam

glorifica which have come down to us are what may be

sixteenth-century performing editions simplifying the 'academic'

notation of the original, where multiple 'colors' and other devices

were employed to distinguish note values and tempo relationships; Bray

has also recognised significant numerical symbolisms which are cleverly

hidden throughout this work. Despite its extreme academic content, the

music's real genius lies in its exceptional beauty. The modern ear may,

however, feel rhythmically unstable during certain passages of this

mass. This effect is partly created by the use of conflicting

mensuration signs (a sort of sixteenth-century time signature) between

the Treble and Baritone parts (in C) and the Alto, Tenor and Bass (in

O), which results in the former voices being notated in duple metre and

the latter in triple metre (Bray reckons that all voices were

originally conceived in O — a metre similar to the modern 9/8

— for the first half of each movement); this, with the occasional

use of triplets (which are usually placed off the beat), creates

wonderfully bold cross-rhythms. Notable examples may be heard in the

'sub Pontio Pilato' trio in the Credo, 'Pieni sunt celi' in the

Sanctus, and the last invocation of the Agnus Dei. Although one could

easily be satisfied with Fayrfax's genius emanating from one's

loudspeakers alone, a fuller appreciation might be gained with an

accompanying score of the music.

Ave Dei patris filia is less an academic exercise than a

marvellous essay in textual setting; the highly mature part-writing

seems to indicate that it was composed towards the end of Fayrfax's

career. This work survives in no less than 15 manuscript sources dating

from the early sixteenth century to the middle of the eighteenth

century and is Fayrfax's most widely-disseminated composition. The

Marian prayer Ave Dei patris filia was very popular in early

Tudor England and printed in at least two contemporary editions of

Salisbury primers. The text was set by a number of English composers

including John Taverner, John Merbecke, Robert Johnson and Thomas

Tallis. (It is evident that the young Tallis closely modelled his early

work Ave Dei on that of Fayrfax. The distribution of voices in

both works is virtually identical, as are the opening head-motifs and

other points of imitation.) Fayrfax employs various compositional

devices such as antiphony and homophony to accentuate certain portions

of the text. Only at the passage 'semper virgo Maria', near the end of

the work, does the use of imitation seem to become an important feature

for all voice parts. The antiphonal 'Amen' which follows is very

reminiscent of a similar ending in Nicholas Ludford's later setting of Domine

Ihesu Christe.

© 1995 David Skinner

A NOTE ON THE SECULAR SONGS

In order to make this set of recordings complete, the secular songs of

Robert Fayrfax will be included together with some other examples from

his contemporaries. The Fayrfax songs are all present in a single

manuscript commonly referred to as the 'Fayrfax Manuscript' (British

Library, Add. MS 5465). Here there is not the variety found in the

so-called 'Henry VIII Manuscript' (British Library, Add. MS 31922),

with its continental songs and instrumental items, nor the differing

forms found in the other important song document of the period, the

'Ritson Manuscript' (British Library, Add. MS 5665). What it does

contain, however, is a large collection of courtly songs concerning the

fortunes of love (mostly serious, but a few in a lighter vein), some

rather more political and topical lyrics, and a fine set of songs with

religious texts. From the list of composers and the reference to

Fayrfax without his doctoral title (which he received in 1504), it

seems probable that the manuscript dates from c.1500.

The three songs recorded here (two by Fayrfax and one anonymous) are

typical in their use of lyrics and in their setting. Sumwhat musyng

was perhaps one of the most popular songs of the early Tudor court,

surviving in no less than five sources; the words are thought to have

been written by Anthony Woodville, Lord Rivers, during his imprisonment

at Pontefract (he was subsequently beheaded in 1483). To complayne

me and That was my joy are both in the conventional English

rhyming style of the period (ababbcc); all three songs are set

within two distinct sections (ignoring the sense of the text), make use

of long ornamental melismata and are all concerned with love. Not for

these poor souls was the twittering of birds in springtime and the

depiction of the beloved as some great deity, but only

'unstedfastness', 'unkyndness withoutenlesse' and 'displesaunce'

(although it is tempting to speculate that the imitation and bold vocal

ornaments of That was my joy poke fun at three lovers all in

pursuit of the same woman and all vying for attention!).

We cannot be sure on what occasion these songs might have been

performed or by whom. They are complex pieces with large vocal ranges

and need extremely competent singers. More importantly the subtle

harmony and sensitive setting of the text is very beautiful, and the

feeling of melancholy thereby created surely is designed to soothe even

the most love-weary breast.

© 1995 Andrew Carwood

SOURCES

Missa O quam glorifica: Cambridge University Library, Gonville

and Cajas MS 667, p. 96 (late 1520s), and Lambeth Palace Library, MS 1,

f. 8v (late 1520s); also in Cambridge University Library, Peterhouse

MSS 471-4, ff. 40v, 38, 44v, 37 (lacks tenor; c.1540s), and Oxford, All

Souls College, Codrington Library, MS SR 59.b.13 (choirbook fragment;

early 16th cent).

Ave Dei patris filia: Warren's edition (Corpus Mensurabilis

Musicae, 17/2) is based on the reading given in the Carver

Choirbook (Edinburgh, National Library, Advocates Lib. MS 5.1.15)

which, when compared with the other readings, has proved to be

defective, especially from 'semper virgo Maria. Amen'. The present

edition is based on Peterhouse MSS 471-4, ff. 31v, 29v, 36, 30 (lacks

tenor), and Oxford, Bodleian Library, MSS Mus. e.1-5, ff. 17v, 16v, 15,

14v, 15v (John Sadler's partbooks; c.1585).

Secular songs: London, British Library, Add. MS 5465 (The

Fayrfax Manuscript): an alternative version of Sumwhat musyng

is recorded here from British Library Add, MS 31922 (Henry VIII's

manuscript).

Plainsong: Graduale secundum morem et consuetudinem preclare

ecclesie Sarum, etc. (Paris, 1527), and Hymnorum cum vatio

opusculum usui insignis ecclesie Sarum subserviens, etc. (London,

1541); both sources in Christ Church Library, Oxford.

Music edited by David Skinner and published by The Cardinall's Musick

Edition

About the recording:

THE LAMBETH CHOIRBOOK AND THE FITZALAN CHAPEL, ARUNDEL CASTLE

The chief sources of the early Tudor mass, and in particular the masses

of Robert Fayrfax and Nicholas Ludford, are the Caius and Lambeth

Choirbooks. Both books are of a similarly large size, uniform in

layout, share similar repertoire, and were largely executed by the same

scribe. We know from an inscription in the Caius book that an Edward

Higgons was responsible for the commission of this manuscript, and the

physical evidence of the Lambeth book strongly suggests that its

production points to the same man. Higgons was a prominent royal lawyer

who held a canonry at St Stephen's, Westminster, where Ludford was

verger and organist from the 1520s. As all of the composers represented

in the Caius book have strong London or Westminster connections it is

generally agreed that it was intended for St Stephen's; the institution

to which the Lambeth book might have belonged, however, could only be

left to speculation until now.

In 1982 an American academic, William Summers, discovered the bass part

of an unknown Ludford votive antiphon in the archives of Arundel

Castle, West Sussex. The provenance of this manuscript was placed

firmly at Arundel by Roger Bowers and argued to have either belonged to

the household of the 10th or 11th Earl of Arundel or, more likely, to

the family's collegiate chapel which still survives (now known as the

Fitzalan Chapel). Perusal of the college accounts by Bowers has shown

that this musically ambitious chapel once boasted the employment of

Walter Lambe and Nicholas Huchyn, whose works are preserved in the Eton

Choirbook. Although it had been known for some time that Edward Higgons

was Master of Arundel College from 1520, it was commented that the post

was 'almost certainly nonresident[ial] (1). It remained unnoticed,

however, that the newly discovered Ludford manuscript was actually

executed by the same scribe as that of the Caius and Lambeth

Choirbooks, establishing an undeniable connection between these

sources. This in turn led to further investigation into contemporary

Sussex records which has revealed that Edward Higgons's brothers

settled in Arundel soon after he took over the mastership; one held the

manor house at Bury (five miles north of Arundel) and the other was a

singingman of Arundel College. Other documents concerning Edward

Higgons's involvement with the college have also come to light. It is

now fairly conclusive from the surviving evidence that Higgons

commissioned the assembly of the Caius book for St Stephen's and the

Lambeth book for his college at Arundel, the scribe of both remains a

mystery.

This is the first recording ever ventured in the Fitzalan Chapel, and

is also the first reunion of music from a late-Medieval English

choirbook to its chapel in modern times. The Cardinall's Musick are

most grateful to the Earl of Arundel and the Trustees of Arundel Castle

for granting permission to record in the beautiful and peaceful

atmosphere of the Fitzalan Chapel. Thanks are also due to Dr John

Robinson and Mrs Sara Rodger for their kind assistance throughout the

project. For further information see David Skinner, 'From Westmynster

to Arundell: new light on Edward Higgons and the Lambeth Choirbook',

forthcoming in Early Music (Oxford University Press).