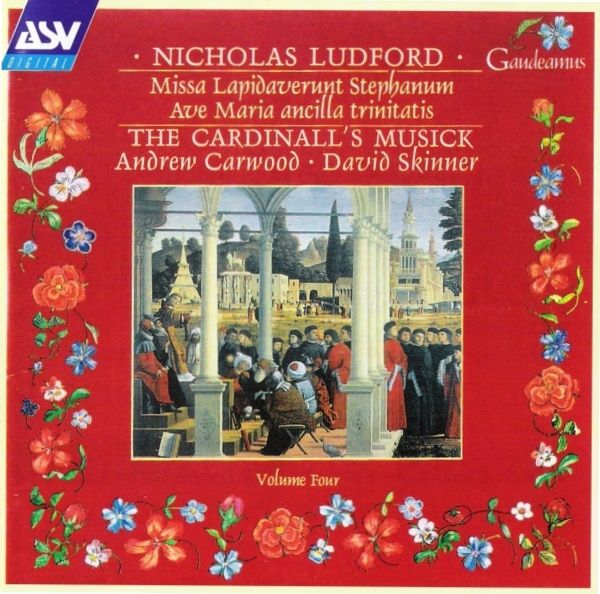

Nicholas LUDFORD / The Cardinall's Musick

Missa Lapidaverunt Stephanum · Ave Maria ancilla trinitatis

AS&V Gaudeamus 140

1994

MISSA LAPIDAVERUNT STEPHANUM

with Plainsong Propers for the Feast of St Stephan

01 - Introitus. Etenim sederunt [4:40]

02 - Kyrie. Rex genitor [2:10]

03 - MISSA LAPIDAVERUNT STEPHANUM. Gloria [9:51]

04 - Gradualis. Sederunt principes [1:57]

05 - Alleluya. Video celos apertos [1:45]

06 - Sequencia. Magnus Deus [3:04]

07 - MISSA LAPIDAVERUNT STEPHANUM. Credo [8:37]

08 - Offertorium. Elegerunt apostoli Stephanum [2:17]

09 - MISSA LAPIDAVERUNT STEPHANUM. Sanctus · Benedictus

[10:19]

10 - MISSA LAPIDAVERUNT STEPHANUM. Agnus Dei [9:35]

11 - Communio. Video celos apertos [1:14]

12 - AVE MARIA ANCILLA TRINITATIS [13:13]

13 - Antiphona. Lapidaverunt Stephanum [0:37]

THE CARDINALL'S MUSICK

Andrew Carwood

Sopranos: Libby Crabtree, Carys Lane, Rebecca Outram

Altos: Robin Blaze, David Gould, William Purfoy

Tenors: Steven Harrold, Robert Johnston, Julian Stocker

Baritones: Matthew Brook, Simon Davies, Robert Evans, Charles

Pott, Matthew Vine

Basses: Jonathon Arnold, Robert Macdonald, Michael McCarthy, Adrian

Peacock

Plainsong only: Simon Davies, Charles Pott, Jonathon Arnold

Producer: David Skinner

Recording Engineer: Martin Haskell

Recorded in All Saint's Church, Petersham

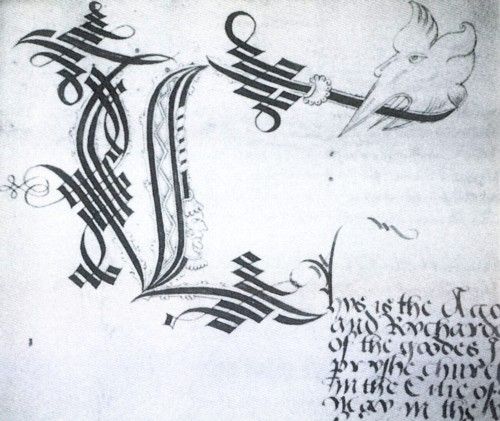

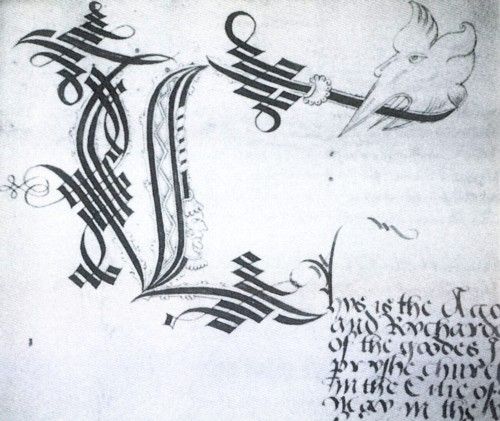

Inside front cover: initial from a titlepage of the churchwarden's

accounts for St Margaret's, Westminster, when Nicholas Ludford was

churchwarden with Richard Castell (1552 - 54), Courtesy of Westminster City Archives

Front cover painting: "Debate of St Stephen" by Vittore Carpaccio

(c.1460/5 - 1523/6)

courtesy of Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan / Bridgeman

Photograph of The Cardinall's Musick: by Lucy Beeb

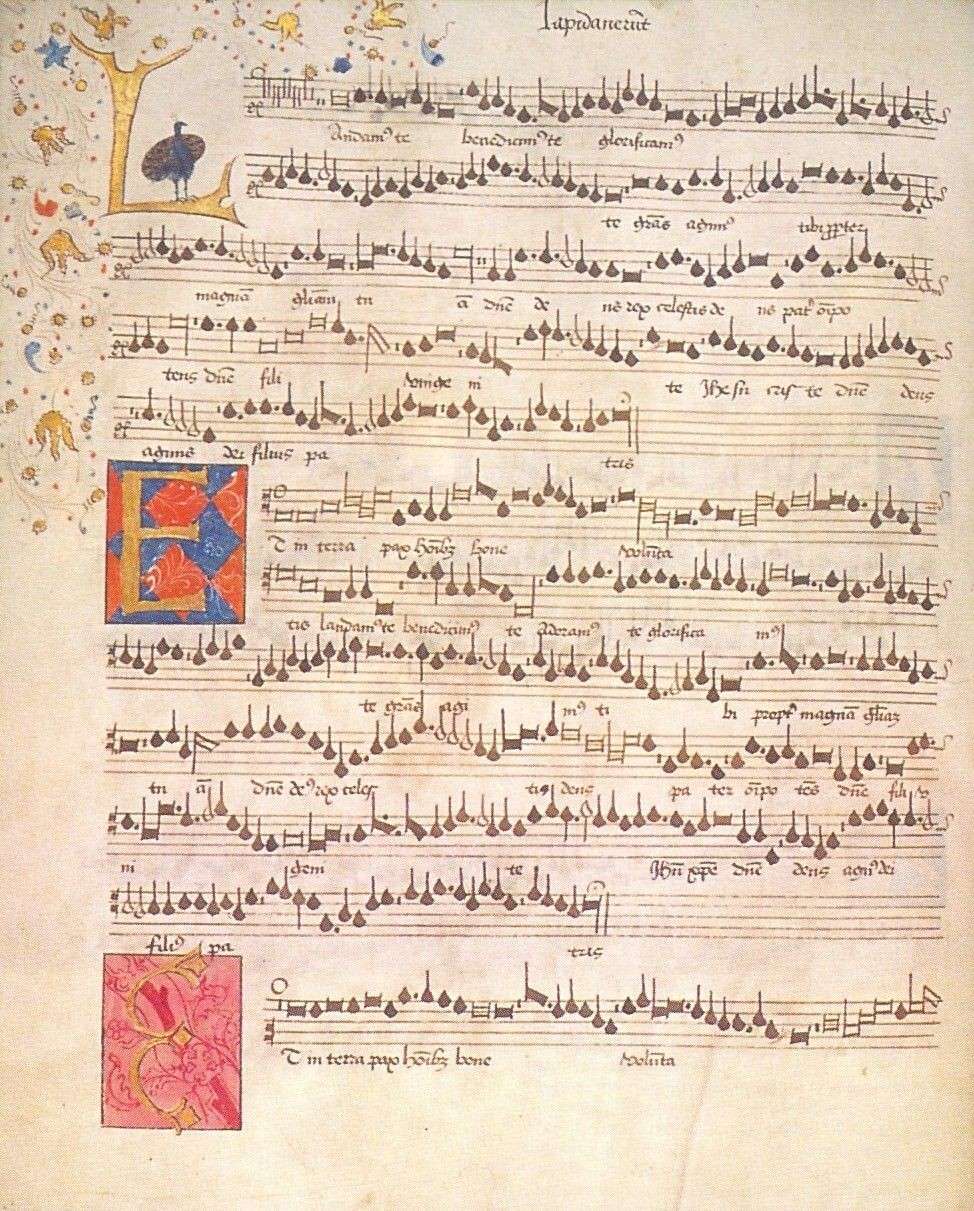

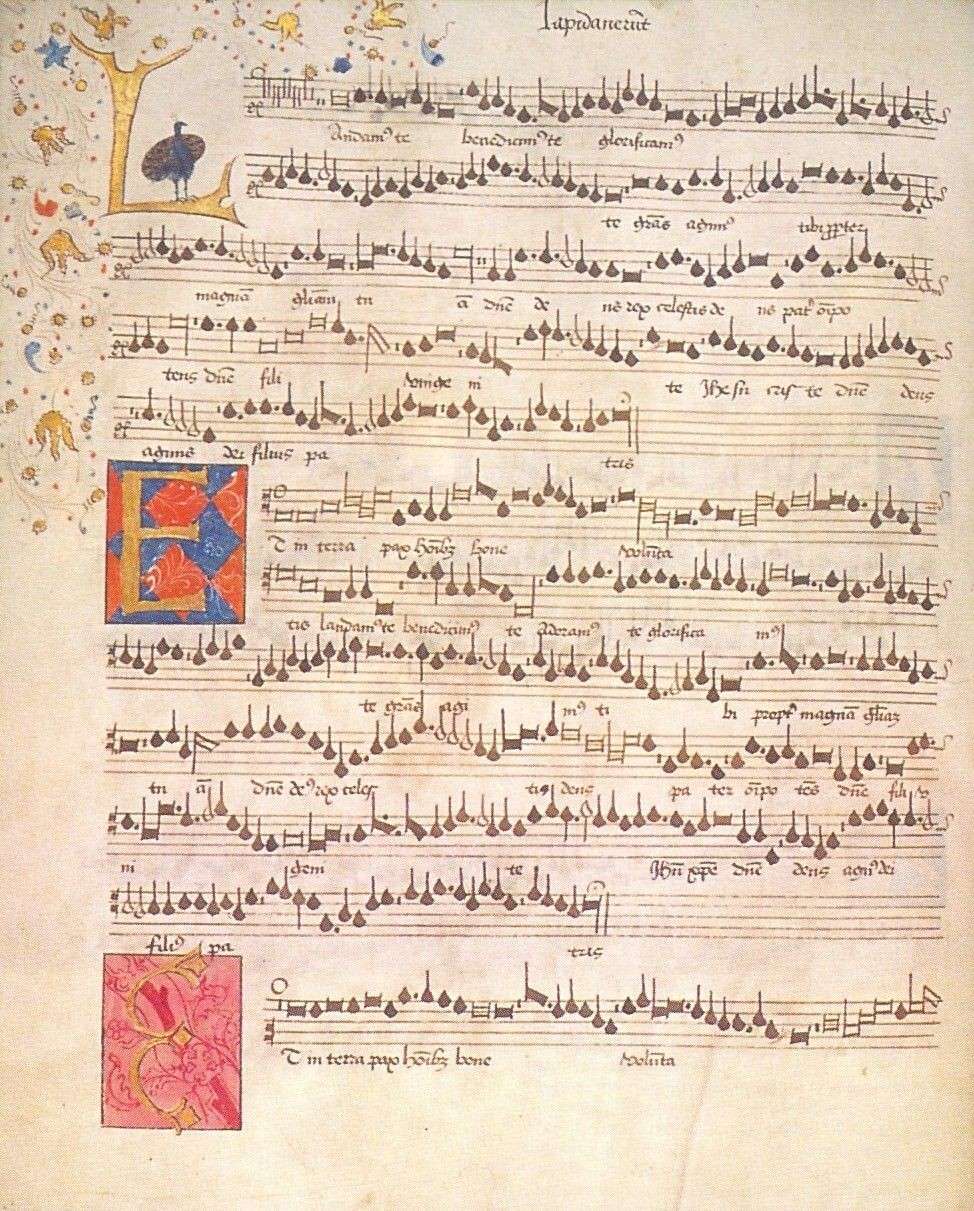

Back cover: Cambridge University Library, Caius MS 667, p.80:

opening of Missa Lapidaverunt Stephanum (Treble, Tenor, Alto)

THE WORKS OF NICHOLAS LUDFORD

Volume IV

The introduction of a composer into the recorded repertoire is often

accompanied with a fresh spark of academic interest. One immediately

recalls, for example, David Wulstan' s work on John Sheppard in the

1970s. Today, as ever, the early music movement continues to develop

and grow beyond the mainstream in search of things unknown and unheard.

In the case of early Tudor polyphony, the first 30 years or so of the

16th century has always been a grey area in terms of both available

recordings and academic literature. This is in no small way owing to

the severe lack of musical and archival sources from this period.

Nicholas Ludford has quickly emerged as one of the champions of these

musically nebulous years. Indeed part of his recent attraction has been

the seemingly anonymous nature of his life and work, and the amazement

at how such a gifted composer could escape public recognition for so

long.

A rebirth in Ludford scholarship was anticipated to follow from the

present series of recordings, although not as soon as has been

realised. Remarkably, around the same time that the scores were being

prepared for the present issue, a wealth of new source material was

discovered which provides a vivid and comprehensive reconstruction of

Ludford's movements in and around the palace of Westminster: included

amongst the archives in Westminster and the London Public Record Office

is a certificate of Ludford's employment at St Stephen's and a number

of documents which tell of his long and continuous association with the

parish church of St Margaret, including his last will and testament. We

now, in fact, have more information concerning Ludford's personal life

and musical career than we do about many of his better known

contemporaries. The following information briefly outlines these

discoveries.*

Ludford arrived in Westminster around 1525 when his name first appears

in the churchwardens' accounts for the parish church of St Margaret.

Nothing is yet known about Ludford's earlier years other than the fact

that he joined the Fraternity of St Nicholas in 1521 (a guild of London

parish clerks, but not necessarily resident in London), although it

would seem that his move to Westminster took place at the height of his

compositional powers and in the prospect of seeking employment in one

of the city's musical centres. Within two years of his arrival Ludford

gained a position in Henry VIII's royal free chapel of St Stephen,

which rested within the precincts of the king's palace. According to

his employment certificate, dated 30 September 1527, Ludford was

granted the offices of verger and chapel organist for life. He was not

the master of the choristers as has been previously assumed; it now

appears that this post was regularly occupied by one of the chapel's

singing men. John Calcost — possibly the composer, John Calcott,

whose work survives in the Peterhouse partbooks — is known to

have held it in 1535 (in 1545 Calcost was succeeded by Thomas Wallys,

who was only to be pensioned off two years later at the dissolution of

St Stephen's). It is not certain what Ludford's main duties as verger

were, however as the highest ranking chapel officer with a well-paid

annual income of 29 2s 6d he was probably in charge of chapel

maintenance, leading the processions, and possibly overseeing the

musical organisation of the daily offices. Interestingly, as organist

he received only 40 shillings in addition to his verger's salary.

Ludford was also heavily active in parish administration at St

Margaret's. He regularly maintained his pew there from 1525 and was

witness to several signings of the churchwardens' accounts between 1537

and 1556. He probably did not participate much in the music-making

there, although in 1533 the churchwardens paid him 20 shillings for 'a

pryke songe boke'. Between 1552 and 1554 Ludford was himself elected a

churchwarden of St Margaret's. These years witnessed the death of

Edward VI and the restoration of the Catholic faith under Mary. It was

also during this time that Ludford suffered the death of his first

wife, Anne, in 1552 and subsequently married Helen Thomas on 21 May

1554. He lived most of his life in Westminster in property on

Longwolstable Street which stood immediately outside the north wall and

gate of New Palace Yard (a short distance from the present clock tower

which houses Big Ben). Ludford died in 1557, possibly from the

influenza epidemic which raged in England at this time, and was buried

inside St Margaret's church on 9 August next to his first wife. His

will was proved on 22 November 1557, St Cecilia's Day.

It may have been shortly after Ludford's appointment to St Stephen's

that he composed his five-voice Mass Lapidaverunt Stephanum,

perhaps in gratitude for his placement there. Because of this

connection, it has generally been assumed that Lapidaverunt is

Ludford's earliest mass. The supreme quality and originality displayed

in all of Ludford's masses, however, seems to suggest that they were

all composed within a relatively short space of time, possibly during

his early years at St Stephen's. Some of Ludford's most inspired

writing may be sampled in his settings of the Agnus Dei; that in Lapidaverunt

is particularly fine, most especially at the words 'dona nobis pacem'.

Here repeating Eton choirbook-like melismas are lovingly set, with

harmonic invention which seems almost to anticipate 17th-century

practice. This is perhaps one of the most magical moments in the entire

corpus of early English polyphony.

The Marian prayer Ave Maria ancilla trinitatis was widely known

in early 16th-century England and circulated in several printed and

manuscript primers (the text was also set by the earlier composer

Edmund Stourton and Ludford's contemporary Hugh Aston). Although

Ludford's setting lacks its tenor part, the work is constructed on the cantus

firmus melody 'Inclina cor meum', which is deployed in the tenor

part of the sections for full choir, and therefore can confidently be

reconstructed. Ludford's Missa Inclina cor meum (similarly

missing its tenor) is also based on this plainsong melody and shares a

similar opening head-motif with Ave Maria ancilla trinitatis,

making them effectively paired works. However, whereas the plainsong

tenor is easily recognisable in the antiphon, it is less apparent in

the mass, suggesting that much of the missing part of the latter was

freely composed. The literary text of the antiphon is essentially a

litany of the virtues of the Blessed Virgin and, like other popular

texts from this period, is preceded by a rubric in several contemporary

sources, proclaiming that 'thys prayer was shewed to saint Bernard by

the messenger of God, saynge that as golde is moost precious of all

other metall soo exedeth thys prayer all other prayers: and who that

deuoutly sayth it shall have a singular rewarde of our blessyd lady and

her swete son iesus'.

Although this is the final instalment of Ludford in our present series,

it should be noted that his entire output is not represented on disc.

Seven complete Lady Mass settings (all for three voices) survive in a

unique source dating from around 1530; these functional works were

intended to be performed in the weekly cycle of masses for Our Lady,

probably in one of Westminster's Lady chapels. By the loss of one or

more partbooks there are also a number of works which exist only in an

incomplete state. Like Missa Inclina cor meum previously

mentioned, Ludford's Missa Regnum mundi also lacks its tenor

part as well as a large portion of the treble. Three out of five voice

parts survive for his antiphon Salve regina mater misericordie,

and we only possess the alto part for his Salve regina pudica mater.

A small fragment of Ludford's four-voice Missa Leroy survives,

and an inventory record tells us of a further three works which are

completely lost — the Masses Tecum principium, Requiem etemam,

and Sermone blando. It is only with the fortunate survival of

the Caius and Lambeth choirbooks (compiled and assembled in Westminster

sometime in the late 1520s or early 1530s) that we are able to sample a

substantial portion of Ludford's musical genius in its complete form

— in sources which were very possibly supervised by the composer

himself.

© 1994 David Skinner

* For further information, see At the mynde of Nycholas Ludford:

New light on Ludford from the churchwardens' accounts of St Margaret's,

Westminster' by David Skinner in Early Music, 22 (1994) p.393, no. 3

(O.U.P., August 1994), p-393.

SOURCES

Polyphony:

Missa Lapidaverunt Stephanum: Cambridge University Library,

Gonville and Caius MS 667, p.80; also in London, Lambeth Palace, MS 1,

p.172.

Ave Maria ancilla trinitatis: Cambridge University Library,

Peterhouse MSS 471-74, ff. 94, 85v, 105, 81 (Tenor 2 editorially

supplied).

Plainsong:

Oxford, Christ Church Library,

Graduale secundum morem et consuetudinem preclare ecclesie Sarum

politissimis formulis (ut res ipsa indicat) alma Parisiorum Academia

impressum (Paris, 1527). Antiphonale ad usum Sarisburiensis

(Paris, 1519).

Music edited by David Skinner, and published by The Cardinall's Musick

Edition