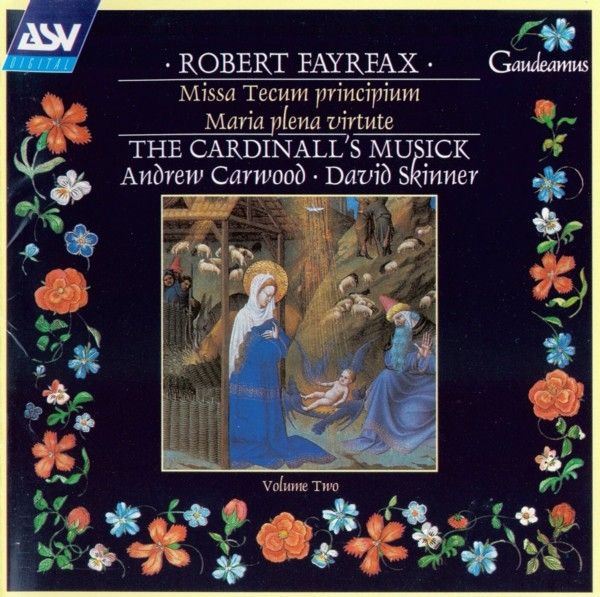

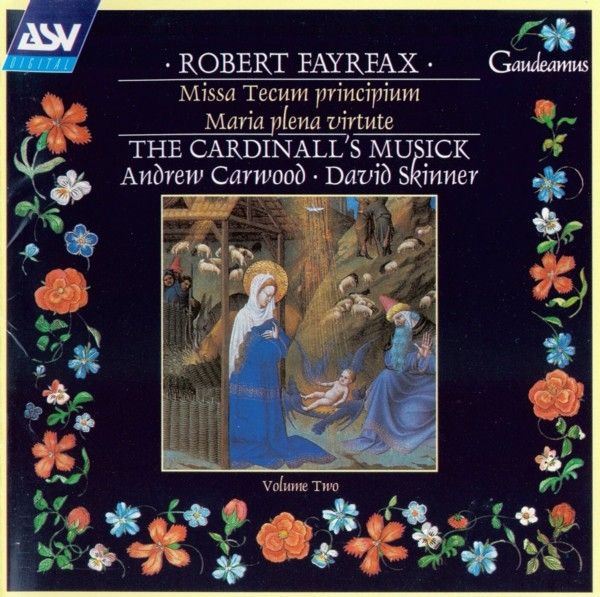

Robert FAYRFAX / The Cardinall's Musick

Missa Tecum principium · Maria plena virtute

medieval.org

AS&V Gaudeamus 145

1995

Robert FAYRFAX

1464—1521

1. Tecum principium [0:44]

plainsong antiphona

Missa Tecum

principium

2. Gloria [11:29]

3. Credo [13:04]

4. Sanctus [12:37]

5. Agnus Dei [12:21]

Music for Recorders

The Frideswide Consort

6. Mese tenor [1:18]

7. O lux beata Trinitas [2:30]

8. Paramese tenor [1:25]

9. Maria plena

virtute [15:25]

THE CARDINALL'S MUSICK

Andrew Carwood

Sopranos: Carys Lane, Rebecca Outram, Olive Simpson

Altos: David Gould, Robert Harre-Jones, Michael Lees

Tenors: Simon Berridge, Julian Stocker, Matthew Vine

Baritones: Matthew Brook, Robert Evans, Donald Greig

Basses: Simon Birchall, Robert Macdonald, Michael McCarthy

THE FRIDESWIDE CONSORT

Recorders: Caroline Kershaw, Jane Downer, Christine Garratt,

Jean McCreery

Editions prepared by

David Skinner

Producer: David Skinner

Recording Engineer: Martin Haskell

Recorded in: Fitzalan Chapel, Arundel Castle, Arundel, 10-11 May

1995

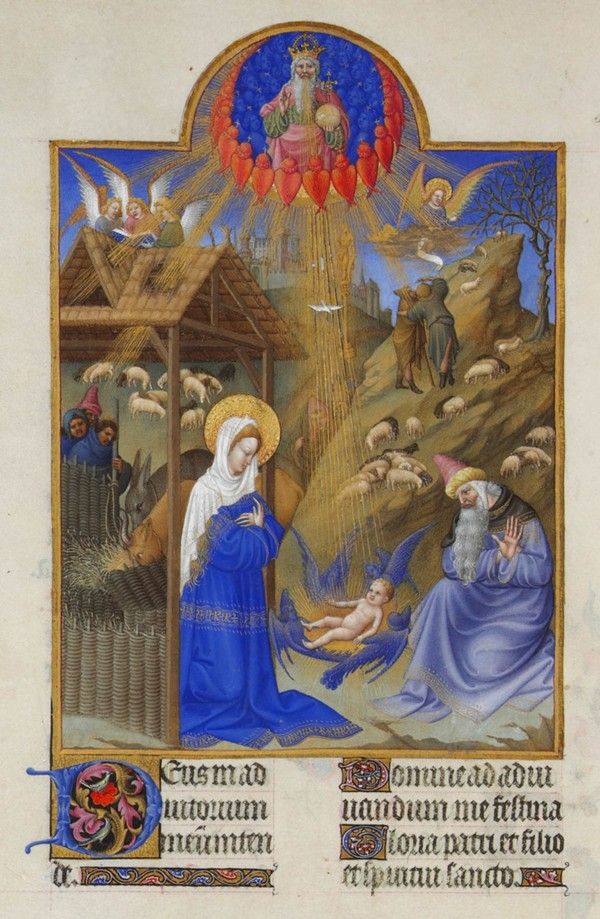

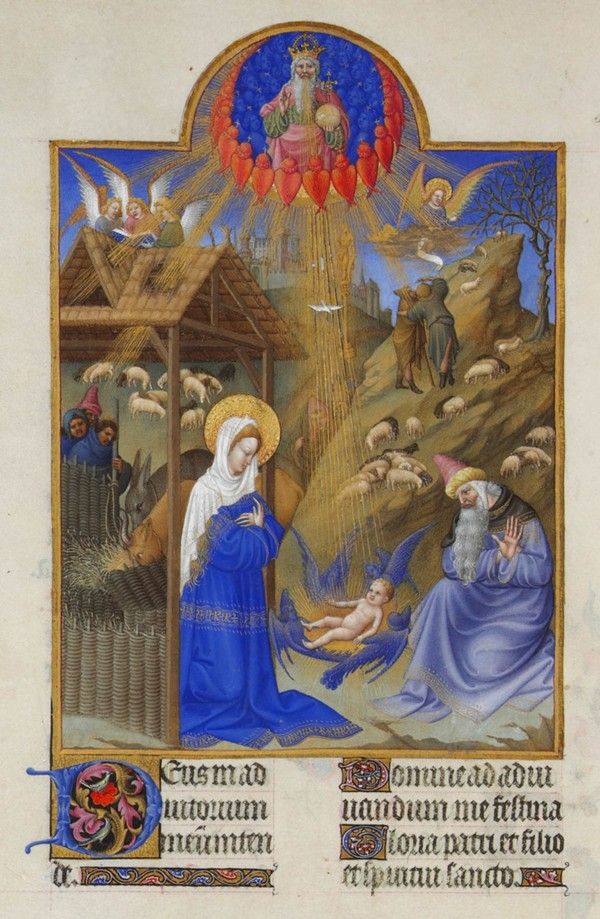

Front cover painting:

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, PE 4935 Ms. 65/1284 f.44v

The Nativity, by Pol de Limbourg. Musée Conde, Chantilly;

courtesy of Giraudon / Bridgeman Art Library

THE WORKS OF ROBERT FAYRFAX

Volume II

The music of Robert Fayrfax and his contemporaries marks the end of a

musical tradition which had its roots in the very foundations of

Britain's ancient chapels and cathedrals. The great English choral

foundations of today technically date from the middle of the sixteenth

century when Protestant reformers replaced the Latin Rite with a new

vernacular service still in use today. A break of more than 450 years

with the earlier Catholic tradition has somewhat clouded our perception

of the circumstances in which these composers lived and worked, and has

distanced us from the ethical and religious beliefs which inspired

their musical creations. The revival of early Tudor polyphony did not

occur until the middle of the present century, and it is only since the

1970s that it has been sung regularly by professional and amateur

choirs. So, effectively for the first time since the English

Reformation, a new performing tradition of this music has emerged,

although this movement has invariably been accompanied by an

impassioned concern for so-called authenticity.

It is virtually impossible to achieve this in early vocal music, and it

is doubtful whether we are much closer to producing a performance which

would be recognisable to early sixteenth-century composers. The main

obstacle is that we have no clues as to what these choirs sounded like,

nor can we be certain of what was then considered a good singing voice

or 'correct' intonation. All we have to go on are the surviving

archival documents, and what can be gleaned from the music itself.

While there can be little doubt that the scoring of early Tudor

polyphony falls into the five basic vocal timbres of treble, alto,

tenor, baritone (or second tenor) and bass (as opposed to the

long-discredited 'high-pitch' scoring of high treble, low treble, alto,

tenor and baritone), it is more difficult to establish precisely how

many singers participated in a given performance. Taverner's choir at

Cardinal College, Oxford (now Christ Church) boasted an unusually large

choir of 12 men and 16 boys, while most other collegiate foundations

worked with much smaller numbers. It is difficult to identify a

specific choir for which Fayrfax composed, although some of his works

can be linked to St Alban's Abbey where he is buried. He was also a

Gentleman of the Chapel Royal from at least 1496, so it is likely that

several of his compositions were written for this elite band of

musicians. However, considering his stature as the most celebrated

composer of his generation, and indeed a favourite of Henry VIII,

Fayrfax's music would have almost certainly been performed in any of

the important choral establishments practised in the art of singing

polyphony — so a variety of 'authentic' performing forces can be

suggested.

All five of Fayrfax's surviving masses are copied into both the Lambeth

and Caius Choirbooks. The former was likely to have been in use at

Arundel College in Sussex after c.1524 and the latter was a gift from

the master of Arundel College, Edward Higgons, to the free royal chapel

of St Stephen in Westminster, where Nicholas Ludford was employed from

c.1521. The performing forces at both institutions were remarkably

similar. Arundel employed six choristers (two of which were in

acolyte's orders) and four professional singing-men. The numbers of the

latter were occasionally bolstered by the employment of one or two

extra clerks and probably some of the residential chaplains, several of

whom are known to have been skilled in polyphony. St Stephen's had

seven boys and four clerks; in addition there were also 13 vicars

choral. Therefore the music copied into the Caius and Lambeth

Choirbooks and thus performed in Westminster and Arundel, respectively,

would have been sung by an average of six or seven boys and four to

probably no more than 12 men (the role of the vicars choral at St

Stephen's and the chaplains at Arundel remains ambiguous). The royal

chapel of St Stephen within the Palace of Westminster was destroyed by

fire in 1834. However, the collegiate chapel of the Holy Trinity,

Arundel, survives intact within the precincts of Arundel Castle, and it

this very chapel which serves as the venue for these recordings of

Fayrfax's music. While The Cardinall's Musick cannot profess to have

reproduced a choral sound that would have been familiar to members of

Arundel College in the late 1520s, there is the assurance that the

acoustics on this recording are virtually the same as those experienced

by our early sixteenth-century counterparts.

This volume in the present series of Fayrfax's complete works takes as

its centrepiece the Christmas Mass Tecum principium. In

contrast with the elaborate and highly cerebral doctorate Mass O

quam glorifica (ASV CD GAU 142), Tecum principium is more

typical of the early Tudor mass cycle as it developed in the works of

Nicholas Ludford. The Mass is also copied into the famous

Forrest-Heyther partbooks and the slightly later Peterhouse partbooks,

which together provide a completely different version of the beginning

of the second section of the Gloria (from 'Qui follia peccata mundi...'

to '...suscipe deprecationem nostram'). This version is stylistically

superior to that found in the Caius and Lambeth Choirbooks and is the

one recorded here. (All of these sources post-date Fayrfax's death in

1521. It would appear that the scribe of Caius and Lambeth either did

not have access to Fayrfax's reworking of this movement —

assuming that it is his — or that it was one which was already

long in use at Arundel and preferred to the revised version.) The Mass

is written in a contemplative style throughout and Fayrfax demonstrates

his expert handling of long and sustained textures, especially in the

sections written for full choir. Short statements of imitation are

frequently introduced, not to accentuate important passages of the text

but to highlight isolated musical ideas (note for example the repeated

motives in each 'Osanna'). The most striking of these is a simple

three-note melodic cell structured around the interval of a fourth

(B♭-G-F) which makes a brief appearance in each movement. At the end of

the Agnus Dei, however, the upper interval of this cell is extended by

one tone (C-B♭-G-F), alternating between the treble and tenor parts

with the alto imitating down a fourth. Listen here for the wonderful

series of unprepared 4-3 suspensions, quite unconventional to the

period although masterfully crafted to a most beautiful and somewhat

modern effect.

Maria plena virtute is arguably Fayrfax's most accomplished

work. The Marian text, which is essentially an account of Christ's

passion, cannot be traced to a contemporary literary source (see Andrew

Carwood's note on its liturgical significance printed below). The work

is conceived on a grand scale and constructed with a number of sections

for a variety of reduced voice combinations, performed here with solo

voices. Fayrfax's known instrumental works, all in four parts, are also

included on this recording. Mese tenor and Paramese tenor

are companion puzzle canons based on a scalic cantus firmus beginning

on A in the former and B in the latter. O lux beata trinitas is

freely composed and begins with a short faburden set to these words in

the manuscript, while the remainder is left untexted. (Fayrfax also

composed a four-part setting of 'Ut re mi fa sol la', of which only the

bass survives.) The written style of these works leaves little doubt

that they were intended for instruments rather than voices; they were

probably composed for private or courtly entertainments. The recorder

consort was certainly a favourite instrumental combination of Henry

VIII. By his death in 1547 the King owned at least 76 recorders, stored

in consorts in elaborately carved cases.

© 1995 David Skinner

SOURCES

Misse Tecum principium: Cambridge University Library,

Gonville and Caius MS 667, p. 142 (late 1520s);

Lambeth Palace Library, MS 1, f. 1v (late 1520s);

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MSS Mus. Sch. e.376-80, ff. 68, 63, 71, 56,

58 (c.1530; the Forrest-Heyther partbooks);

Cambridge University Library, Peterhouse MSS 471-4, ff. 45v, 42, 49v,

41 (c.1540s; lacks tenor).

Maria plena virtute: Cambridge, Peterhouse MSS 472-4, ff.

7, 9v, 7v (lacks treble and tenor);

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MSS Mus. e.1-5, ff. 46, 45v, 46, 43, 41v

(c.1585; 'John Saldler's partbooks);

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Tenbury MS 1464, f. 24 (c.1575; bass only);

London, British Library, MS Roy.Mus.Lib. MS 24.d.2, f. 146v (c.1600,

John Baldwin; verse 'Rex amabilis' only, attrib. to Taverner);

also listed in a manuscript index which dates from the early 16th

cent., now in Merton College Library, Oxford (MS 62.F.8).

Instrumental music:

Mese tenor and Paramese tenor: London, British Library,

Add. MS 31922 (Henry VIII Manuscript), ff. 57-8. See D. Stevens, ed. Music

of the Court of Henry VIII, Musica Britannica, 18 (London: Stainer

and Bell, 1973), p. 106;

O lux beata trinitas: London, British Library, Add. MS 4911. See

E. B. Warren, ed. Robert Fayrfax: Collected Works, Corpus

Mensurabilis Musicae, 17/2 (1959-66), p. 57.

Music edited by David Skinner. Missa Tecum principium and Marla plena

virtute are published by The Cardinall's Musick Edition, P. O. Box 243,

Oxford, ENGLAND.

A NOTE ON Maria plena virtute

So great was the devotion to Our Lady in pre-Reformation England that

many texts were written in her honour, for Mary is the great allegory

of the Church. She was present when the Church was born, that is when

Christ died. Through her sorrow, as expressed in the Stations of the

Cross for example, those in prayer can relate to the pain of the

Passion and Crucifixion. She makes understandable the mystery of

redemption through Christ's death and focuses human feeling in an

accessible way.

Votive antiphons produced in early Tudor England had various forms, but

the setting Maria plena virtute seems exceptional. It is closer

to a private musing on the matter of the Passion rather than a formal

prayer to the Virgin. It begins in a predictable way with an invocation

to Mary, but, after the opening trio and duet, moves swiftly to the

Passion narrative, with a gentle swaying back and forth from narrative

and personal interjection rather like the chorus in a play.

Whilst contemplating the forgiveness for which he so longs, the

penitent is reminded of Christ's forgiveness on the Cross and so begins

the first reference to St Luke's Gospel (23, vv. 39-43). Then the focus

is widened as the writer moves to the scene at the foot of the Cross

when Christ commits the care of his mother to the beloved disciple (St

John 19, vv. 25-7). Here again the writer casts his mind back to the

words from St Mark concerning the son of Man who comes not to be served

but to serve (St Mark 10, v. 44). Then a jolt back to the present and

St John, however not simply 'I thirst' as in the gospel narrative, but

'Sitio salutem genuis' (I thirst for the salvation of Man), which once

again is the cue for personal musing before a movement to Matthew (27,

v. 46) and back to John (19, v. 30). There is further drawing on

scripture at the mention of the sword piercing Mary's heart (St Luke 2,

v. 35) and the mission of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus (St John

19, vv. 38-42). The end of the work returns the attention to Mary and a

glimmer of light given by the words 'regina caeli' (a Paschaltide

reference to the Virgin).

It is difficult to ascribe any particular season to votive antiphons,

yet Maria plena virtute, with its concentration on the gospel

passion narratives and its ironic reference to 'regina caeli', seems

ideally suited to Holy Week. This is an intensely personal devotion to

which Fayrfax has responded in a most personal style. There is little

melismatic writing compared with his contemporaries; indeed the

syllabic word setting in places seems more reminiscent of the Continent

than England. 'Ora pro me', pleads the writer (not the usual 'ora pro

nobis'), to which Fayrfax responds with remarkable melodic and harmonic

subtlety and with such care over the word setting, the like of which

would not be a regular feature in English church music until later in

the century.

© 1995 Andrew Carwood