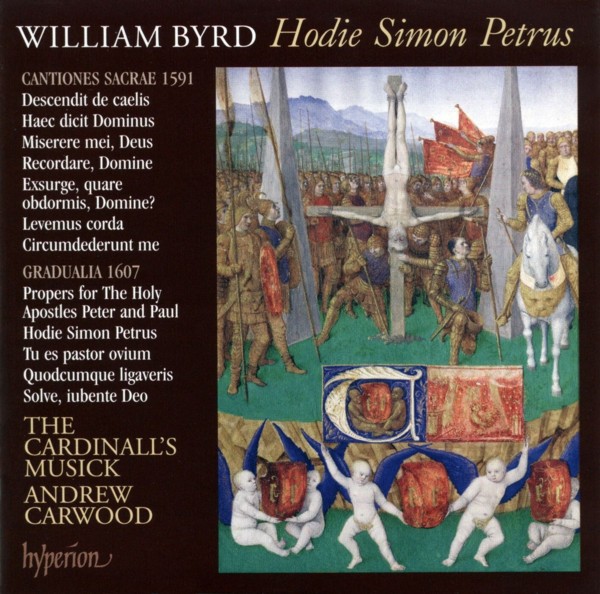

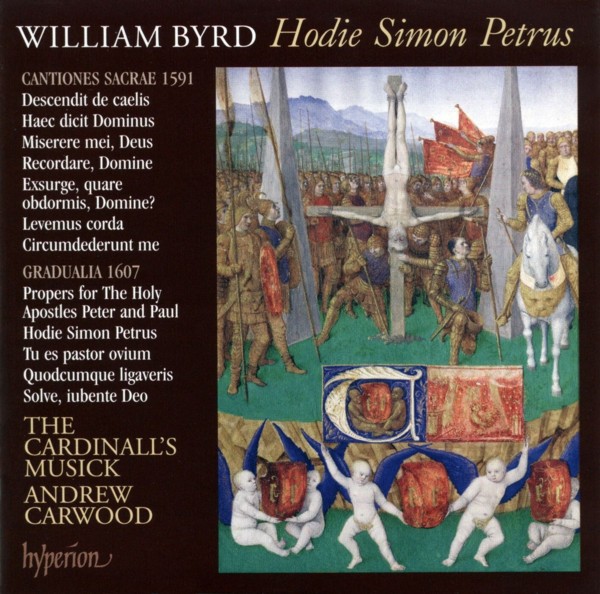

William BYRD. Hodie Simon Petrus

Byrd Edition vol.11 / The Cardinall's Musick

hyperion

hyperion CDA67653

febrero de 2009

grabado en noviembre de 2007

Fitzalan Chapel, Arundel Castle, UK

William Byrd

(1539/40-1623)

The Cardinall's

Musick Byrd Edition Vol.11

Hodie Simon Petrus

Cantiones Sacrae 1591

Gradualia 1607

01 - Descendit de

caelis [5:34]

02 - Tu es pastor ovium [2:03]

03 - Miserere mei, Deus [3:05]

04 - Circumdederunt me [4:50]

05 - Quodcumque ligaveris [4:16]

06 - Recordare, Domine [6:05]

07 - Exsurge, quare obdormis, Domine? [4:18]

08 - Laetania [8:57]

09 - Nunc ccio vere [5:23]

10 - Constitues eos principes [3:08]

11 - Tu es Petrus [2:13]

12 - Levemus corda [4:45]

13 - Hodie Simon Petrus [3:53]

14 - Solve, iubente Deo [2:40]

15 - Haec dicit Dominus [6:44]

#1: SAATTB

#2, 5: AATTBB

#3: SATBarB

#4, 15: ATTBarB

#6, 7, 12: AATTBB

#8: BarˇATTB

#9, 10, 11, 13, 14: AATTBarB

THE CARDINALL’S MUSICK

Andrew Carod

soprano: Carys Lane, Rebecca Outram

alto: Patrick Craig, David Gould, Caroline Trevor

tenor: Steven Harrold, Julian Stocker

baritone: Robert Evans

bass: Edward Grint, Robert Macdonald

FUNDAMENTAL CHANGE in the Church is

rarely easy to achieve with unanimity and without pain and division.

The people of early sixteenth-century England had only ever known one

belief system, a complicated set of rules preserved and developed by a

Church with its spiritual head in Rome. It governed their daily lives

and although the conjoining of Church and State led sometimes to storms

and tempests and division, it was ultimately secure. The Reformation

destroyed certainty and left people only with questions. The English

owed allegiance to their monarch and to their country but the spiritual

focus of their lives, that which dealt with their immortal soul, was

the Roman Church. Who had the right to tell the people what do? The

King of England or the Bishop of Rome?

Musicians were not exempt from these weighty matters and in the early

days they were all forced to react. John Merbecke, the Windsor-based

composer, decided that his extended Latin votive antiphons were now

useless, threw them to one side and embraced reform. Nicholas Ludford,

the prolific composer and churchwarden of St Margaret’s,

Westminster, also seems to have stopped composing his Latin works, but

not because of any desire for change, rather because of a deep

dissatisfaction with the way in which religious policy was unfolding.

Time is a great healer however and, as the century progressed, people

forgot the old ways. Those who had grown up under Elizabeth’s

intelligent and sensible settlement took the reformed Church as a

given. Composers such as Thomas Weelkes, Orlando Gibbons and Thomas

Tomkins found themselves part of a uniquely English institution which

allowed them the freedom to produce exceptional music. Yet, for those

who still held their allegiance to Rome these days were hard, full of

persecution and deprivation. William Byrd had grown up not with the

reforms of Elizabeth but with the Catholic restoration of Mary. Born in

1539 or 1540, he was probably a chorister in London and was a teenager

during the politically and artistically stimulating early years after

Mary’s accession. It must have been at this time that a desire

for England to remain Catholic became embedded in his heart.

As a devout Catholic and a brilliant musician it is perhaps a little

strange that Byrd should never have travelled abroad. All eyes looked

to Italy for art, manners and etiquette and many left England either to

experience the various styles and fashions of the Continent or to flee

the Catholic persecution. Much of Byrd’s life however was spent

in London (apart from a brief spell as the young organist of Lincoln

Cathedral) until he moved to a quieter life in the countryside of Essex

in the 1590s. He was truly an English composer and perhaps it is

possible to see in this move, this nesting in the countryside, an even

more definite statement of his beliefs. His writing is unmistakably

English and it is likely that his view of Catholicism was also deeply

English: these two elements are clearly brought together in his music.

With the exception of the Litany, the pieces contained on this disc,

the eleventh devoted to the Latin Church music of Byrd, are from two

sources: the Cantiones Sacrae of 1591 (published at the end of

his time in London) and the second book of motets entitled Gradualia

from 1607 (which contains music probably written for the Catholic

community based around Ingatestone Hall in Essex). The seven motets

from 1591 show Byrd to be preoccupied with thoughts of desolation,

loss, deprivation and separation—thoughts which were obsessions

for the recusant Catholic community. Yet it is rare for Byrd not to

offer salvation in his music, indeed this is his constant refrain. Each

piece provides at least a glimmer of hope and often contains an

outright statement of positive thought.

If ever a piece was designed to speak directly to the Catholic

community, it is the five-voice Haec dicit Dominus. The text

speaks of the Old Testament character Rachel, whose sons have been

murdered—a telling choice of subject for those who were

witnessing the execution of their supporters and priests. Rachel is

bereft and destitute and she refuses all comfort. But the answer from

the Lord is positive and forward looking—‘et est

spes’—‘and there is hope’. The Latin words are

incredibly direct and simple, and so powerful and unexpected is this

statement that the music almost stops. These are exactly the words that

the people needed to hear and Byrd makes sure they are as clear as if

an angel of the Lord had appeared and spoken.

Descendit de caelis has a ravishing texture. Byrd proudly

displays his English heritage by setting a pre-Reformation Sarum rite

text involving a cantus firmus (a favourite device of John Sheppard and

his contemporaries) complete with dissonances and false relations. Yet

as so often with Byrd there is a nod in the direction of modern ideas,

at the words ‘lux et decus’ (‘the light and

glory’) he uses a hopeful, upward-rising phrase which he was to

develop further in the set of Propers for the Feast of Candlemas

(recorded on Volume 8 of this series), which celebrates Christ as the

light of the world.

Thanks to the efforts of editors in the twentieth century some of

Byrd’s works have become well established gems of the repertory.

One such is the five-part Miserere mei, Deus. A clear

homophonic opening asking for mercy moves quickly into beautiful

imitation. The text contains several words which seem to elicit

particularly powerful melodies from Byrd, especially

‘iniquitatem’ (‘wrongdoing’) and

‘misericordiam’ (‘mercy’); indeed the melody of

this latter word was one that he was to take forward and use in the

monumental Infelix ego.

Circumdederunt me shows Byrd in a more mournful light but also

in a more contemporary one. He employs a number of telling harmonic

shifts which he must have learned from his Continental colleagues and

developed in his younger years. The piece moves upwards in tessitura

and intensity at the repeated words ‘O Domine, libera animam

meam’ (‘O Lord, free my soul’) before subsiding as if

exhausted. Similar in feel is Recordare, Domine, a piece asking

for God to recall his promises to mankind and not to destroy the earth.

Fear and awe dominate in the first half of this piece but some warmth

enters later at the mention of the ‘holy city’ before Byrd

returns to his opening plea for mercy for the world. There is a more

positive approach in Levemus corda with its faster harmonic

pulse and flexible melodic lines, but the subject matter is still the

same. Exsurge, quare obdormis, Domine?, by contrast, is one of

the most energized pieces in the 1591 Cantiones Sacrae. Byrd

uses a taut, sinewy melody as he demands that God should arise, not

once but three times.

In the Gradualia volumes of 1605 and 1607, Byrd produced music

for many of the Feasts of the Church’s calendar. One of the most

complex sets is the six-voiced group of motets in honour of St

Peter and St Paul (presented here together with a Litany in honour

of the saints). It may seem strange that the two most significant

saints of the Church should have to share one Feast Day but in this

sharing there is a powerful statement. The combination underlines the

power of the Church itself, built on the rock of Peter and on the

teachings of Paul. Byrd responds with music that it is cerebral,

complex, witty and powerfully rhythmic. Indeed the set contains one of

the most remarkable pieces of writing that Byrd ever produced. At the

words ‘dicit Dominus Simoni Petro’ (‘says the Lord to

Simon Peter’) in Quodcumque ligaveris Byrd indulges in a

fascinating explosion of fast notes which require considerable vocal

dexterity in terms of technique and tessitura. It is perhaps his way of

highlighting that Peter’s authority (and thus the authority of

all Bishops of Rome) came directly from Christ himself.

Unusually Byrd has varied the scoring in this set of pieces. Two of

them (Tu es pastor ovium and Quodcumque ligaveris) are

scored for a divided low bass part whereas the others are for the more

usual AATTBarB combination. This strongly suggests that they were

written at different times rather than all composed for one occasion

(perhaps Byrd was even writing for the singers whom he knew would be

present). The angst of the 1591 pieces is banished in these settings

where Byrd gives his imagination free rein. Perhaps he felt more

comfortable in Essex away from London; perhaps he was feeling the wind

of change blowing through the country as Elizabeth gave way to James VI

of Scotland who had promised (but was never to deliver) greater

toleration for Catholics. We will probably never know, but the

remarkable fact is that Byrd even in his later years could produce the

most modern-sounding and the most energetic music that he had ever

written.

He provides only three pieces (Nunc scio vere, Constitues eos

principes, and Tu es Petrus) for Mass itself. There is no

Communion setting which is certainly unusual and he relies on the fact

that the Alleluia verse Tu es Petrus has the same text as the

Offertory and that the same music could be used twice (a common

occurrence throughout the two books of Gradualia). The set is

completed by the short Solve, iubente Deo and the beautiful Hodie

Simon Petrus which, appropriately enough in a collection of texts

which otherwise refer only to St Peter, reserves its most telling music

for the mention of the death of St Paul.

On this disc it seemed appropriate to include a Laetania

(Litany) in honour of all the saints. This is beautiful yet entirely

functional music, a world away from the high art form of the other Gradualia

pieces. Yet at the words of the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) Byrd cannot

resist writing music with a more impassioned nature. Not surprising

from a man for whom texts, their context and subtext, were clearly

everything.

ANDREW CARWOOD © 2009