Nimbus NI 5125

1988

Nimbus NI 5125

1988

01 - Alleluia, I heard a voice [2:56]

02 - Give ear, O Lord [5:31]

Evening Service for five voices

03 - Magnificat [6:20]

04 - Nunc Dimittis [3:10]

05 - Hosanna to the Son of David [1:51]

06 - When David Heard [4:56]

07 - O Lord, Grant the King a Long Life [2:01]

08 - Give the King Thy Judgements [5:31]

09 - Gloria in Excelsis Deo [3:01]

Ninth Service

10 - Magnificat [8:37]

11 - Nunc Dimittis [6:48]

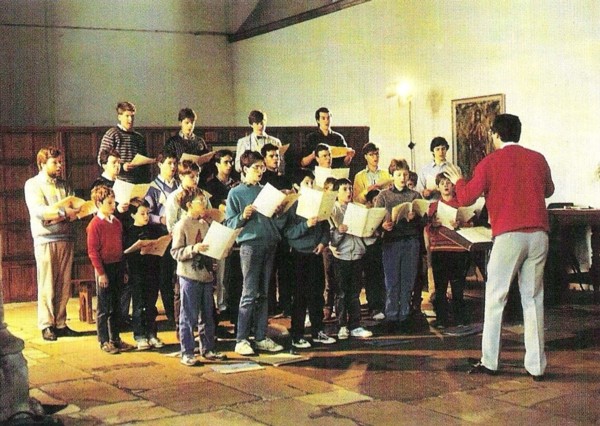

Christ Church Cathedral Choir

Stephen Darlington

Choristers

James Ridgway

George Godsal

Martin Illingworth

Benjamin Hughes

William Smith

Kieron Maiklem

Michael Forbes

Thomas Morris

James Weeks

Gulliver Ralston

James Gorick

Michael Speight

Peter Weir

Angus McCarey

Ranjeet Guptara

Lay and Academical Clerks

Altos:

Stephen Carter I II

Richard Roberts I

Andrew Olleson

Stephen Taylor

Nicholas Barker

Tenors:

Edwin Simpson

Matthew Vine

Ciaran O'Keefe

Andrew Carwood

Basses:

David Le Monnier

Paul Martin

Tim Bennett

Edward Wickham

Organist: Laurence Cummings

I Soloist in "Give ear O' Lord"

II Soloist in "Give the King Thy Judgements"

Recorded at Dorchester Abbey, OxfOrdshire,

13th and 14th March, 1988

by Nimbus

THOMAS WEELKES

The period during which Thomas Weelkes (c. 1576—1623) composed

most if not all of his church music — roughly the first two

decades of the seventeenth century — was also a period of decline

and fall in his professional career and private life. Biographical

details elude us, and it may never be known why the young successful

madrigal composer of the 1590s ended his days in disgrace among the

cathedral authorities of Chichester, dismissed from his post as

organist on grounds of his being a habitual common drunkard and a

notorious swearer and blasphemer. Weelkes evidently aspired to higher

things: several of his anthems and services were written not with

Chichester in mind but for the more sumptuous services and ceremonies

of the Chapel Royal, and it is clear that Weelkes did have some

informal contact with that institution. But he never consolidated the

London connection to the extent that he could leave provincial

Chichester. Perhaps the debauched habits of which he was later accused

were more the cause of stagnation in his career than the effect of it.

Set beside William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons, the two outstanding

figures in church music during the reign of James I, Weelkes must have

appeared a curiosity. His music was weakest in the respects those two

composers rated most highly: Weelkes had never been particularly

interested in sensitive word-setting, and he probably lacked the

ability — or perhaps the patience — to compose counterpoint

of any great sophistication or skill. His talents lay rather in the

making of thrilling textures, ravishing sonorities, exhilarating

rhythms and, when the moment seemed right, marvellously spicy

harmonies. Those are the hallmarks of the extraordinary sequence of

madrigals Weelkes wrote when still barely out of his teens. What the

aged Byrd and serious-minded Gibbons can have thought of the anthems

and service music Weelkes subsequently composed, often in a style

instantly recognizable from the madrigals, it is not difficult to

imagine. Success for Weelkes came posthumously: later generations of

church musicians have warmed to this impulsive, colourful music, and

today his works have a secure place in the cathedral repertory.

The selection of music recorded here falls roughly into two sequences,

one representing works of a general nature composed for no specific or

known destination, the other, pieces that Weelkes probably or possibly

wrote with courtly circles in mind. Although they span some twenty

years of work, only one piece can be dated with any accuracy. But

chronology is in a sense unimportant; the fact that stylistically these

anthems and services project such a strong sense of a single, unique

personality testifies to Weelkes's confidence in and satisfaction with

his musical language, and they show little evidence of a mind searching

for new modes of expression and alternative musical structures. Modem

as Weelkes's madrigalisms may be by the standards of English church

music of the day, at heart his music is embedded in tradition and

nourished by a strong sense of heritage.

Like so many Jacobean anthems, Weelkes's Alleluia, I heard a voice

was prized equally highly by domestic musicians and church choirs. It

may even originally have been intended for solo voices and a consort of

viols rather than for liturgical use. One manuscript source specifies

it "For All Saints' Day", but any joyful occasion would be well served

by this confident, forthright and strongly rhythmical work, with its

pealing chains of Alleluias. Give ear, O Lord another

all-purpose anthem, differs both in the nature of its text — a

penitential, and at the time well-known poem by William Hunnis —

and in the scoring for verses (soloists accompanied by organ)

alternating with passages for full choir. Text and texture here fuse

together: each stanza closes with the refrain "Mercy good Lord" set for

full choir to related but always slightly varied music.

In common with so many of Weelkes's other settings of the morning and

evening canticles, the Evening Service for Five Voices survives in a

fragmentary state. In fact, performance of this particular work has

been made possible today only after major surgery. The vocal lines

themselves are completely lost; all that remains of the setting is an

organ part that conflates the choir's music into what two hands can

play at the keyboard. Various editors have attempted to unravel the

tangle; the version performed here is by David Wulstan. Reasonably

substantial by the standards of the day, the service is set for full

choir without solo verses, but it includes some enterprising

subdivisions, in particular the passage for high four-part choir in the

Nunc dimittis — inspired no doubt by the words "to be a light to

lighten the gentiles".

The four anthems that follow all seem in one way or another to be

'royal' works. Hosanna to the Son of David like Gibbon's

setting of the same text, may have been composed as a welcome song for

James I or one of his sons; certainly the exuberant style suggests

ceremonial rather than everyday use. When David heard together

with a host of textually-related pieces by Weelkes's contemporaries,

was almost certainly prompted by the premature death of Henry Prince of

Wales, in 1612. It sounds like a solemn madrigal, and indeed it might

have been written with domestic performance in mind. The magnificent

seven-voice anthem O Lord, grant the King a long life takes as

its text two verses from Psalm 61 which, in Weelkes's setting assume

the quality of a paean of praise for James I and a prayer for his

preservation. This is another full anthem; by contrast, Give the

King thy judgements which draws similarly patriotic words from

Psalm 72, is scored for verses, although on a scale larger than usual

for the day.

Gloria in excelsis Deo stands somewhat on its own. Technically

the work is a carol — which is to say, by Tudor definition, that

it consisted of a central verse (others may be lost) flanked on either

side by a refrain, and has a strong seasonal element, in this case

Christmas. Church choirs soon absorbed the piece into their

repertoires, but it is likely that this work too was first sung by solo

voices in the hall or chamber of a Jacobean house.

The final work is by far the largest on record, and the most extended

composition known by Weelkes. It belongs to the category of the 'great'

service, conceived on the grandest scale and written for a special

occasion or destination. Again the Chapel Royal comes to mind, and the

fact that at several places in the service Weelkes quotes blocks of

music from the anthem O Lord, grant the King a long life

strengthens that possibility. Nominally scored for a seven-part choir,

Weelkes in practice freely subdivides and regroups his forces from

verse to verse in a conscious effort to recall the sonorities and

textual variety of English music a hundred years earlier. Some of the

scorings remain conjectural, however: like the Evening Service for Five

Voices, the Ninth Service survives in a defective state, and David

Wulstan has provided music for the voice-parts that are missing from

the manuscripts.

© John Milsom 1988