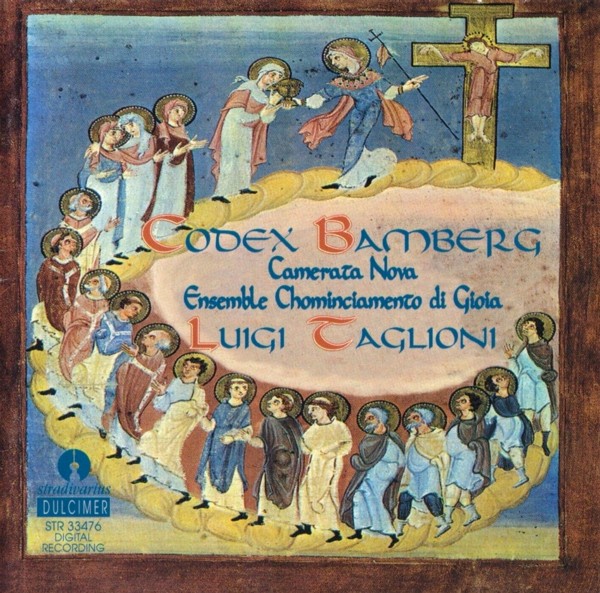

medieval.org

Stradivarius STR 33476

1997

medieval.org

Stradivarius STR 33476

1997

1. Je ne chant pas ~ Talens m'est pris de

chanter ~ Aptatur ~ Omnes [1:23]

XCII — soprani PR MV, contralto SB, tenore FS

2. Ave, virgo regia ~ Ave, plena gracie ~ Fiat

[2:46]

III — contralto SB, tenore FS, viella LP, arpa OE

3. In seculum breve [1:02]

viella LP, liuto MS, dulcimer GT, arpa OE

4. Entre Adan et Henequel ~ Chief bien seans ~ Aptatur [1:29]

XXIV — soprano PR,contralti IV SB

5. Ave, plena gracie ~ Salve, virgo regia ~ Aptatur [3:18]

LXXXVI — soprano MV, contralto IV, flauto GT, viella LP, arpa OE, liuto MS

6. Neuma [1:24]

flauto GT, corno bovino MS, viella LP, arpa OE

7. Ave, in styrpe spinosa ~ Ave, gloriosa ~ Manere

[2:01]

II — tenore FS, bassi GV ST

8. El mois de mai ~ De se debent ~ Kyrie [2:45]

XXVI — soprano PR, contralto IV, tenore FS

9. In seculum viellatoris [2:43]

vielle GR LP MS

10. Mout me fu griès ~ In omni frate tuo ~ In seculum [2:35]

XLVII — soprani PR MV, contralto IV

11. Entre Copin ~ Je me cuidoie ~ Bele Ysabelot

[2:42]

LII — soprani MV PR, contralto IV

12. Virgo [0:58]

vielle LP GR, flauto GT, arpa OE

13. Pouvre secours ~ Gaude chorus ~ Angelus

[3:07]

XXXVI — soprano MV, contralti IV SB

14. Chorus Innocencium ~ In Bethleem ~ In Bethleem

[2:29]

XLIV — contralti IV SB, viella LP, percussioni EDF

15. In seculum d'Amiens breve [1:58]

flauto GT, vielle LP GR, liuto MS

16. O Maria, virgo davitica ~ O Maria, maris stella ~ Misit Dominus [2:17]

LXXV — soprani MV PR, flauto GT, vielle LP GR

17. O miranda ~ Salve, mater ~ Kyrie [2:13]

LXXXV — soprani PR MV, contralti IV SB, tenore FS, bassi GV ST

18. In seculum longum [1:02]

flauto GT, vielle LP GR

19. Agmina milicie ~ Agmina milicie ~ Agmina [2:37]

VI — soprano PR, contralto IV, basso GV

20. Quant flourist ~ Non orphanum ~ Et gaudebit

[2:18]

LXVII — contralti IV SB, tenore FS, basso GV

21. In seculum d'Amiens longum [1:05]

flauto GT, viella LP, arpa OE

22. Mout me fu griès li ~ Robins m'aime ~ Portare [2:02]

LXXXI — soprano MV, contralti IV SB

23. Or voi je bien ~ Eximium ~ Virgo [3:39]

XXXII — soprano MV, contralto SB, viella LP, arpa OE

24. Ave, Virgo regia ~ Ave, gloriosa ~ Domino [2:19]

I — soprano PR, contralto SB, tenore FS

25. Mors que stimulo ~ Mors morsu ~ Mors [1:32]

LXI — soprano PR, basso GV, soprano MV, tenore FS, contralto IV, basso ST

Camerata Nova

Camerata Nova

Matelda Viola (MV) • soprano

Paola Ronchetti (PR) • soprano

Ida Viola (IV) • contralto

Sara Borioni (SB) • contralto

Fabrizio Scipioni (FS) • tenore

Guido Vetere (GV) • basso

Stefano Terribili (ST) • basso

Ensemble Chominciamento di Gioia

Luigi Polsini (LP) • viella

Gianfranco Russo (GR) • viella

Marco Salerno (MS) • liuto, corno bovino, viella

Olga Ercoli (OE) • arpe

Giovanni Tardino (GT) • dulcimer, flauti diritti medievali

Elisabetta Di Filippo (EDF) • percussioni

Luigi Taglioni, direttore

Registrazione: Cripta delle Ancelle della Carita. Roma 19 & 26 . I - 2 & 9 . II . 1997

Direzione artistica: Giovanni Caruso & Luigi Taglioni

Produzione: Giovanni Caruso

Tecnico del suono e montaggi digitali: Studio Mobile "I MUSICANTI", Roma

Traduzione dal francese antico: Manna Punzi

Traduzione dei testi latini (esclusi i tracks 10, 13, 20, 23): Volter Navone

Il Codice di Bamberga

è un manoscritto della Biblioteca reale di Bamberga (coll. Ed.IV.6)

proveniente dalla biblioteca della cattedrale. Il codice appartiene

agli ultimi anni del XIII sec. o ai primi anni del secolo successivo e

si divide in due parti: la prima comprende cento mottetti politestuali

– in latino, in francese o in entrambe le lingue – a tre voci, uno a

quattro voci, un cunductus e qualche brano strumentale; la seconda

parte contiene un trattato di musica Practica artis musice

scritto nel 1271 da un certo maestro Amerus.

Il Codice di Bamberga

è un manoscritto della Biblioteca reale di Bamberga (coll. Ed.IV.6)

proveniente dalla biblioteca della cattedrale. Il codice appartiene

agli ultimi anni del XIII sec. o ai primi anni del secolo successivo e

si divide in due parti: la prima comprende cento mottetti politestuali

– in latino, in francese o in entrambe le lingue – a tre voci, uno a

quattro voci, un cunductus e qualche brano strumentale; la seconda

parte contiene un trattato di musica Practica artis musice

scritto nel 1271 da un certo maestro Amerus.

Il codice di Bamberga è estremamente interessante per chi voglia

ripercorrere l'evoluzione del mottetto.

L'origine del Mottetto, individuabile in Francia all'inizio del XIII

secolo nell'ambiente musicale della Cattedrale di Notre-Dame a Parigi,

è legato ad una forma giunta in quel tempo alla sua massima fioritura:

l'Organum.

La forma dell'Organum a due voci (duplum) melismatico era

stata già coltivata nell'abbazia di S. Marziale di Limoges, e

rappresentava una novità rispetto all'antico Organum procedente

nota contro nota (punctum contra punctum). Ma solo nell'ambiente

di Notre-Dame l'Organum accoglie l'importantissima innovazione

della struttura ritmica che, nota come “ritmica modale” e con la

prevalenza assoluta della suddivisione ternaria, considerata perfecta,

caratterizza e condiziona lo sviluppo della polifonia fino al termine

del XIII secolo; sempre a Notre-Dame lavorano le prime due personalità

artistiche che emergono dall'anonimato grazie ad un trattato anonimo

inglese della fine del XIII secolo (Anonimo IV): Leoninus (ca.

1160-1190) e Perotinus (ca. 1190-1230).

L' Organum di Notre-Dame è una composizione polifonica a 2, 3 o

4 voci (organum duplum, triplum, quadruplum) in cui le parti

scritte superiormente si sviluppano su di un cantus firmus

liturgico chiamato tenor, attinto soprattutto dai canti del Proprium.

Il termine “tenor” deriva dal falto che tale voce (o strumento)

tiene ferme, in valori lunghissimi non misurati, le note del frammento

gregoriano, reso in tal modo irriconoscibile. Le voci superiori (duplum,

triplum, quadruplum) sviluppano i loro melismi organizzati secondo

i modi ritmici.

La maggior complessità e articolazione è raggiunta negli Organa

tripla e quadrupla di Perotinus; in essi si trovano, alternati alle

sezioni di organum vero e proprio con il tenor a note

lunghe non misurate, del passi in cui il tenor è costituito da

note ravvicinate, organizzate secondo i modi ritmici, di modo chela

polifonia diviene più serrata: queste sezioni in stile di “discantus”,

che si avvicinano cioè all'antico stile “nota contro nota”, erano

chiamate clausulae o puncta.

L'unica differenza tra le clausole e i mottetti più antichi è il fatto

che le prime mantengono nelle “voces organales” lo stesso testo

del tenor (le voci sono scritte in partitura e il testo compare

solo sotto al tenor, la voce più in basso), mentre i secondi

presentano un nuovo testo nelle parti superiori.

La politestualità caratterizzerà la forma del mottetto per più di due

secoli; ben presto si adottò la scrittura a parti separate sullo stesso

foglio, per risparmiare preziosa pergamena.

Il mottetto originario deriva dunque dalla clausula mediante

l'applicazione del procedimento, già ben noto in ambito gregoriano,

della tropatura: l'adattamento sillabico a melismi preesistenti di un

nuovo testo che parafrasa, letterariamente e concettualmente, il testo

liturgico affidato al tenor.

Già nelle clausole perotiniane si trova un elemento distintivo del

mottetto: l'ordinamento del tenor secondo formule ritmiche che

si ripetono costantemente, preannuncio della futura costruzione

“isoritmica” sviluppata e affinata fino al punto di saturazione nel XIV

sec. dall'Ars Nova.

Esempi della prima fase evolutiva legata alla clausula si

possono ascoltare nella presente incisione alla traccia 25 (dall'Organum

perotiniano “Alleluia. Christus resurgens...”) e alla traccia 19.

L'etimologia del termine “motetus” sembra debba ricercarsi nel

francese “mot” che significava composizione poetica, in opposizione a “son”,

“cans”, “chanson” indicanti la composizione melodica; il

diminutivo “motet” designerebbe una breve composizione poetica.

Il mottetto compie una rapida evoluzione e acquista una posizione

privilegiata fra le forme dell'Ars Antiqua: presto appare una terza

voce (triplum) e più tardi una quarta (quadruplum). Il

termine motetus designa la voce immediatamente superiore al tenor

(nell'Organum era il duplum) ma per estensione indica la

composizione nel suo complesso; lo stesso vale per i termini triplum

(la voce sopra al motetus) e quadruplum (la voce sopra

al triplum).

Fino al termine del XIII sec. la forma a tre voci si afferma per

copiosità di produzione; il Codice di Bamberga (1280/1300, Alta

Franconia), preso in considerazione nel presente disco, contiene

infatti ben cento mottetti a tre voci, uno solo a quattro voci, un conductus

a tre voci e sette mottetti strumentali a tre voci scritti in partitura.

Qualche mottetto ci è giunto in vari manoscritti con elaborazioni

diverse che documentano tutte le fasi della sua evoluzione (un esempio

è il mottetto della traccia 14, presente in diverse versioni, in ben

sei manoscritti).

L'evoluzione seguente all'aggiunta delle voci fu l'adattamento alla

parte del triplum di un nuovo testo, ulteriore parafrasi del tenor.

Fino a questo punto il mottetto sembra rientrare a pieno diritto tra le

forme funzionali ad un'esigenza di “amplificatio” del servizio

liturgico, accanto e in sostituzione degli Organa.

Ma si incontrano già in età molto antica mottetti in lingua volgare,

per lo più francese. Il mottetto francese sarebbe, secondo la tesi più

diffusa, una derivazione da quello latino, mediante sostituzione del

testo originale con un nuovo testo francese, secondo la tecnica del

“contrafactum”.

Ma siccome contrafacta francesi compaiono già a fianco di

antichi organa, il processo può essere stato a volte inverso,

cioè mottetti francesi originali, derivati da una clausola, possono

aver dato vita a nuovi contrafacta in latino. Alcuni mottetti

francesi, infine, sono creazioni originali, il che testimonia il

progressivo allontanarsi della forma dalla primitiva destinazione

liturgica. Nel mottetto francese il tenor, certamente

strumentale quando è liturgico, non ha più quel valore simbolico che

gli derivava, nel mottetto latino, dall'affinità concettuale con le

altre parti; esso ha solo la funzione di sostegno costruttivo musicale.

Verso la fine del XIII sec. i compositori non esiteranno ad adoperare

come tenor la melodia di una chanson profana, spesso nella

forma tipicamente francese del rondeaux. Si ascolti la traccia 22 del

disco: la parte del motetus, abilmente sovrapposta a un tenor

liturgico, è la chanson iniziale del Jeu de Robin et Marion

(1282) di Adam de la Halle, l'unico compositore noto dell'Ars Antigua,

famoso anche come troviere.

Così il mottetto, a causa dell'uso della lingua volgare e

dell'introduzione di elementi profani, per il carattere sempre più

artificioso e complicato, divenne oggetto di condanna da parte

dell'autorità ecclesiastica; allontanato dalle funzioni sacre, divenne

una composizione politestuale profana di elevata raffinatezza tecnica,

apprezzabile da un'elite di intenditori o persone colte. Poteva forse

accadere che fra gli esecutori comparisse anche l'autore. Il mottetto

della traccia 4, attribuito a Adam de la Halle, sembra suggerire come

ambiente di produzione e di fruizione quello degli studenti

dell'università di Parigi.

Altri mottetti rivelano una destinazione cortese come quello alla

traccia 11 in cui il tenor costituito da una chanson profana.

Nella traccia 8 troviamo invece un mottetto ispirato da una questione

di diritto canonico. Il carattere raffinato ed esoterico del mottetto

si accentuerà ancor più nel periodo dell'Ars Nova trecentesca (Ars

Subtilior).

Testimonianza del successo della forma e del fervente lavoro di

tropatura, adattamento e sostituzione, è il gran numero di

rimaneggiamenti che uno stesso mottetto poteva subire, constatabili dal

confronto fra i diversi monoscritti.

I rimaneggiamenti potevano coinvolgere, oltre che il testo, anche la

parte musicale, più spesso il triplum, essendo la parte

aggiunta più di recente (il mottetto della traccia 8 si trova con un

diverso triplum nel codice di Montpellier). Più rari i casi di

rimaneggiamento del tenor o del motetus: una parte di motetus

poteva diventare il triplum o il tenor di un altro

mottetto (vedi traccia 10: nel codice di Montpellier il motetus

appare al triplum di un altro mottetto). Un'ulteriore

elaborazione poteva consistere, come abbiamo detto, nell'aggiunta di

una quarta voce (traccia 1, unico quadruplum dalla raccolta di

Bamberga: esso presenta la combinazione di due tenores

liturgici).

In un'epoca di assoluta preminenza della musica vocale nelle fonti

manoscritte, meritano una menzione i mottetti strumentali della

raccolta di Bamberga.

E' stato ipotizzato che già nel mottetto liturgico, come anche negli organa,

le note del tenor fossero sostenute da strumenti; inoltre si può

pensare che, al di fuori dei ristretti circoli di letterati e studenti

dell'Università parigina, il mottetto fosse eseguito e diffuso dagli

jongleurs. Questi ultimi viaggiavano provvisti di strumenti musicali e

accedevano in chiostri, abbazie, piazze, sale principesche; il loro

repertorio spaziava attraverso generi adatti per le diverse occasioni:

canti monodici religiosi e profani, chansons di trovieri, rondeaux,

conductus, mottetti.

In che misura gli strumenti contribuivano all'esecuzione? All'epoca non

esisteva il concetto di stile strumentale; gli strumenti potevano

tutt'al più raddoppiare o sostituire le voci di composizioni aventi un

testo. Tuttavia nel repertorio popolare del XIII secolo (v. soprattutto

il ms. dello Chansonnier du Roy (Pb3) della Biblioteca

Nazionale di Parigi) troviamo ductia, estampies e danses

royales come generi di danza puramente strumentali.

Uno strumento molto usato era la viella, per la sua precisione ritmica,

ma si ricordi che non vi era alcuna preoccupazione di affidare

l'esecuzione a certi strumenti piuttosto che ad altri; ecco perché

assume un valore altamente eccezionale l'indicazione “in seculum

viellatoris” del mottetto della traccia 9.

Altri strumenti utilizzati nel XIII secolo sono arpe, flauti, dulcimer,

corno di mucca, liuto.

Una caratteristica della notazione dei brani strumentali è, a parte

l'assenza di testi, l'uso intensivo delle ligaturae,

raggruppamenti di più note sotto un'unica figura (nel mottetto vocale

sono assenti nelle parti superiori in quanto il trattamento del testo è

sillabico). In base a testimonianze manoscritte si possono dedurre le

seguenti combinazioni: una voce ed uno strumento; due voci ed uno

strumento (come in molti mottetti del Codice di Bamberga); tre

voci e uno strumento; due voci e due strumenti. Gli strumenti inoltre

potevano produrre preludi, interludi, postludi, o anche inserirsi fra

le voci prendendo il posto di parti che tacevano momentaneamente.

Gli ultimi sette mottetti del Codice di Bamberga (tracce 3, 6,

9, 12, 15, 18, 21) sono senza dubbio destinati ad un'esecuzione

strumentale. E' frequente in essi l'impiego dell'hoquetus,

artificio consistente nell'interrompere frequentemente le linee

melodiche mediante pause alternate tra le voci (dal latino hoccitare

= tagliare).

I mottetti delle tracce 18, 9, 3, 21, 15 possono considerarsi

variazioni sullo stesso tenor “in seculum”, allora molto

celebre, preso dal Graduale di Pasqua “Haec dies”; addirittura

il brano della traccia 3 “in seculum breve” identico a quello

della traccia 18 “in seculum longum” scritto in notazione

ritmica diversa, ovvero breves invece di longae; lo

stesso dicasi della traccia 15 rispetto alla traccia 21.

Giovanni Scaramuzza Fabi

Bamberg Codex is a manuscript held by the

Royal Library of Bamberg (coll. Ed.IV.6), originating from the

Cathedral Library. The Codex dates from either the end of the

13th century or the beginning of the 14th, and is in two parts: the

first part consists of a hundred three-part motets – in Latin, French

or in both languages –, one four-part motet, a conductus and

some instrumental pieces; the second section consists of a musical

treatise entitled Practica artis musice, written in 1271 by a

certain Amerus.

The Bamberg Codex is of extreme interest to the student of the

motet. The motet originated in France at the beginning of the 13th

century as part of the musical tradition of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame

in Paris, and is a close relation of a form which was reaching its apex

at that time: the Organum.

The melismatic Organum was a form for two voices (duplum)

which had been developed by the Abbey of St. Martial in Limoges, and

was a step forward from the ancient note against note organum

(punctum contra punctum). However, it was the musicians of Notre

Dame who incorporated the innovative rhythmic structure, known as

"modal rhythm", dominated by ternary subdivision and considered

"perfect", which characterised and conditioned the development of

polyphony until the end of the 13th century. Further, it was at Notre

Dame that the first two major artistic personalities emerged from

obscurity, thanks to an anonymous English treatise from the end of the

13th century (Anonymous IV): Leoninus (c. 1160-1190) and Perotinus (c.

1190-1230).

The Organum of Notre Dame is a polyphonic composition for two,

three or four voices (organum duplum, triplum, quadruplum) in

which the upper voices are developed over a liturgical cantus firmus

known as the tenor, based largely on the Proprium. The

term "tenor" derives from the fact that the voice or instrument

had, for lengthy, unspecified times, to hold the notes of the Gregorian

fragment, thus rendered unrecognizable. The upper voices (duplum,

triplum, quadruplum) developed their melisma according to the

rhythmic modes.

It is in Perotinus' triple and quadruple organa that we find

the greatest levels of complexity and articulation. They consist of

sections of authentic organum with the long, unmeasured notes

of the tenor, and passages in which the tenor is made

up of closely-written notes, organised according to the rhythmic modes,

in such a way that the polyphony is tightened; these discantus

sections, which resemble the ancient "note against note" style, were

known as clausulae or puncta.

The only difference between these clausulae and the older

motets is the fact that, in the former, the voces organales

sing the same text as the tenor (the voices are written in the form of

a score, and the text only appears below the tenor, the lowest voice),

whilst the latter have new text for the upper voices.

These multiple texts characterised the motet form for more than two

centuries; it was soon common practice to include separate parts on the

same sheet, in order to use less parchment, which was extremely

expensive.

Thus the original motet derives from the clausulae via the use

of the procedure, well-known in Gregorian circles, of troping, i.e.

adapting new text syllabically to existing melisma, paraphrasing,

literally and conceptually, the liturgical text entrusted to the tenor.

In Perotinus' clausulae we can already see a distinctive

element of the motet; the ordering of the tenor according to

constantly repeated rhythmic formulae, a forerunner of the

"iso-rhythmic" construction developed and refined to saturation point

in 14th century Ars Nova.

Examples of the first evolutionary phase linked to clausulae

can be heard on track 25 of this CD (from Perotinus' Organum

"Alleluia. Christus resurgens...") and on track 19.

The term "motetus" would appear to originate from the French "mot"

which signified a poetical composition, as opposed to a "son",

"cans" or "chanson", indicating a melodic composition; the

diminutive "motet" signified a brief poetical composition.

The motet evolved rapidly, attaining a privileged position amongst the

various forms of the Ars Antiqua. A third voice (triplum) soon

appeared, and later a fourth (quadruplum). The term "motetus"

designated the voice immediately above the tenor (in the Organum

this was the duplum) but, by extension, could indicate the

whole composition; the same was true for the terms triplum (the

voice above the motetus) and quadruplum (the voice

above the triplum).

The form for three voices dominated the market until the end of the

13th century; the

Bamberg Codex (1280/1300, High Frankony) contains no less than a

hundred three-part motets, one four-part motet, one three-part conductus

and seven three-part scored instrumental motets.

Some of these motets have survived in other manuscripts with different

adaptations which testify to the various phases of the music's

evolution (for example, the motet on track 14 of which various versions

exist in six manuscripts).

Following the addition of the voices, the next evolutionary stage was

the adaptation of the triplum role to a new text, a further

paraphrasing of the tenor role. Up to this point the motet

still counts as one of the forms used for the "amplificatio" of

the liturgy, alongside and in place of the organa.

Motets in languages other than Latin, especially in French, date back

to ancient times. The French motet, according to the most popular

theories, derives from the Latin motet, via the substitution of the

original text with a new text in French using the technique known as contrafactum.

However, French contrafacta exist which are contemporary to

ancient organa, and thus the process was almost certainly

inverted from time to time – in other words, original French motets,

deriving from a clausola, could well have been the basis of new

contrafacta in Latin. Moreoever, certain French motets are

undoubtedly original creations, which is indicative of the progressive

evolution of the form from its original liturgical function. In French

motets the tenor, instrumental in its liturgical form, no

longer has the symbolic function which derived, in the Latin motet,

from its conceptual affinity with the other parts; its only function

now is that of musical support.

Towards the end of the 13th century, composers frequently adopted, for

their tenors, the melody from a profane song, often in the

typically French form of a rondeaux. Track 22 on this CD is an example:

the motetus which brilliantly replaces the liturgical tenor,

is the opening song from the Jeu de Robin et Marion (1282) by

Adam de la Halle, the only known composer of Ars Antiqua and a famous

trouvère.

Thus the motet, after the adoption of the vulgar tongue and the

introduction of profane elements, developed a far more complex

character, became the object of official ecclesiastical condemnation

and was banned from church services. It grew into a polytextual profane

composition of extreme technical complexity, appreciated by a highly

cultivated elite. Composers were frequently performers. The motet on

track 4 of this CD, attributed to Adam de la Halle, would appear to

have as its background the University of Paris.

Other motets reveal courtly origins, such as that on track 11 in which

a popular song has been used for the tenor. Track 8, on the

other hand, would appear to have been inspired by a debate on canonical

law.

The refined, esoteric character of the motet was exaggerated further by

the development of Ars Nova during the 13th century (Ars Subtilior).

The success of the motet can, in fact, be seen from the huge number of

re-workings and adaptations which a single motet could undergo.

Comparison of different manuscripts clearly reveals this.

These adaptations could affect both text and music, especially the triplum,

being the most recently added part (a version of the motet on track 8

exists with a different triplum in the Montpellier Codex).

Re-workings of the tenor or motetus role are more

unusual: a motetus part could become the triplum or tenor

of another motet (see track 10, in the Montpellier Codex the motetus

has been used as the triplum of another motet). The

compositions were frequently embellished further by the addition of a

fourth voice (see track 1, the only quadruplum in the Bamberg

collection, which consists of a combination of two liturgical tenors).

In an era dominated by vocal music, as we can see from manuscript

sources, the instrumental motets in the Bamberg Codex deserve

particular attention.

The hypothesis has been advanced that, in early liturgical motets and organa,

the tenor role was performed by an instrument; moreover, it is

perfectly feasible that motets were not only performed by a restricted

circle of scholars and students, but were also part of the repertoire

of the jongleur. Jongleurs travelled around with their musical

instruments, performing in cloisters, abbeys, market squares and

princely courts and their repertoire covered a wide variety of music,

suitable for different occasions: religious and profane monodic chants,

troubadour songs, rondeaux, conductus and motets.

To what extent they used their instruments in these performances is

difficult to establish. At the time the concept of instrumental style

did not exist, instruments could support or even substitute voices in

compositions with text. However, in 13th century popular repertoire

(see especially the Chansonnier du Roy (Pb3) manuscript in the

National Library in Paris) we find examples of purely instrumental

dances such as ductia, estampies and danses royales.

A popular instrument at this time was the viella, favoured for its

rhythmic precision, but it should be remembered that instruments were

regarded as interchangeable, which explains why the indication "in

seculum viellatoris" on the motet on track 9 is so exceptional.

Other instruments popular during the 13th century were the harp, flute,

dulcimer, cow's horn and lute.

The notation of instrumental pieces was characterised, apart from the

absence of texts, by the frequent use of ligaturae, groups of

several notes under a single figure (in vocal motets these were absent

in the upper parts given the syllabic treatment of the text). From

manuscript evidence it is possible to see the following combinations:

one voice and one instrument; two voices and one instrument (as in many

of the Bamberg Codex motets); three voices and one instrument;

two voices and two instruments. The instruments could also perform

preludes, interludes, postludes or insert themselves between the voices

in place of temporarily silent parts.

The final seven motets in the Bamberg Codex (tracks 3, 6, 9,

12, 15, 18, 21) were undoubtedly composed for instrumental performance.

They include the frequent use of hoquetus (from the Latin hoccitare

= to cut), a device which consisted of the frequent interruption of the

melodic line by pauses alternated between the voices.

The motets on tracks 18, 9, 3, 21 and 15 can be considered variations

on a famous tenor "in seculum" taken from the Gradual for

Easter "Haec dies": the work on track 3 "in seculum breve"

is identical to that on track 18 "in seculum longum" written

with a different rhythmic notation, breves instead of longae,

and the same can be said of tracks 15 and 21.

Giovanni Scaramuzza Fabi

Translataion: The Chain Music Services Ltd. - UK