Music from the Spanish Kingdoms

Circa 1500

medieval.org

CRD 3447

1989

1. Juan del ENCINA (1468-1529). Oy comamos y bebamos [1:47]

2. Tres morillas me enamoran [1:26]

3. Alonso HERNÁNDEZ (fl. early 16th c.). Tres moricas me enamoran

[4:10]

4. Gagliarda, mi racomando [0:57]

5. Gagliarda, lombarda [1:02]

6. Gagliarda, el tu tu [1:17]

7. Adrian WILLAERT (1480-1562). Vacchie letrose [1:38]

8. Marchetto CARA (1465-1525). Liber fui un tempo in foco [3:35]

9. Francesco da MILANO (1497-1543). La Spagna

[2:16]

10. Bartolomeo TROMBONCINO (1470-1585). Come haro donque ardire

[3:02]

11. Alonso MUDARRA (1508-1580). Tiento para harpa

[0:40]

12. Juan VÁSQUEZ (1500-1560). En la fuente de un rosel [1:54]

set by Diego PISADOR (1509-1557)

13. JOSQUIN (c. 1440-1521). Ile fantazies de Joskin

[2:02]

14. Loyset COMPÈRE (d. 1518). Scaramella [1:16]

15. Johannes MARTINI (1440-1497). Fuge la morte

[2:12]

16. Juan del ENCINA. Entra mayo y sale abril [1:22]

17. Gentil dama [2:39]

18. Juan del ENCINA. Más vale trocar [1:39]

19. Juan del ENCINA. Ay triste que vengo [1:30]

20. Si habéis dicho, marido [1:21]

21. Diego ORTIZ (c. 1510-1570). Ricercar [1:51]

22. Diego ORTIZ. O felici occhi mei

[2:23]

23. Giovan Thomas di MAIO (d. 1563). O trezze bionde anci capelli d'oro

[4:49]

24. Miguel FUENLLANA (1525-1585). Fantasia sexta

[1:53]

25. Sagaleja del Casar [1:04]

26. Diego ORTIZ. Passamezzo moderno

[2:48]

27. Johannes MARTINI. Cayphas [2:18]

28. Giovan Thomas di MAIO. Tutte le vecchie son maleciose

[2:23]

29. ALONSO [Hernández?]. La tricotea

[1:35]

30. Juan del ENCINA. Si habrá en este baldrés

[2:12]

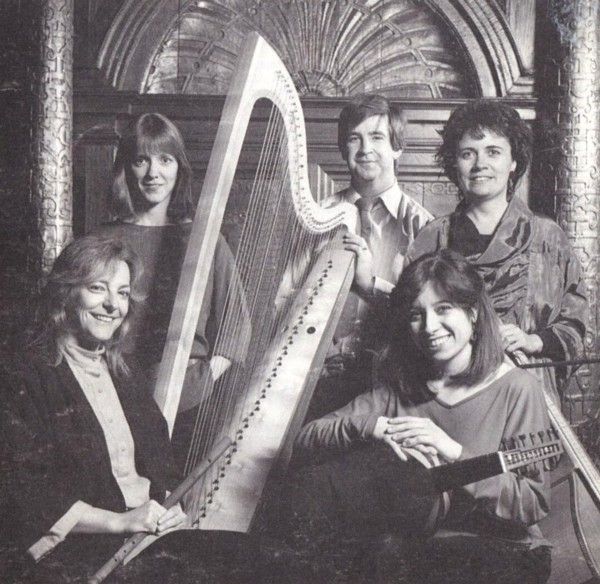

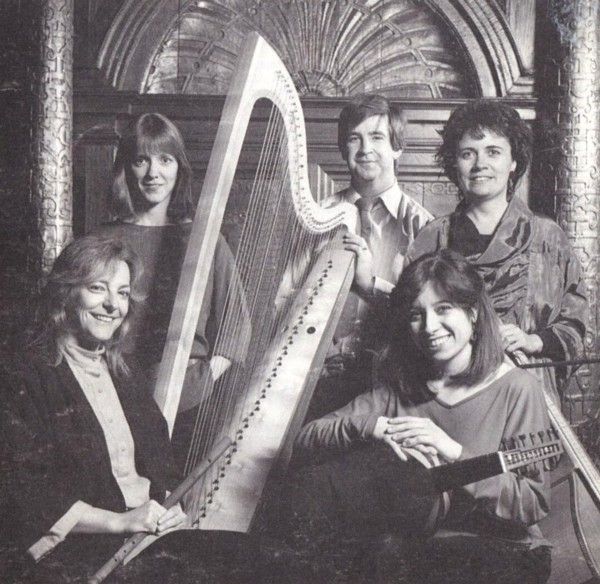

Circa 1500

Nancy Hadden

Nancy Hadden, flute, recorder & crumhom

Emily Van Evera, soprano

Erin Headley, viola da gamba, lirone & fiddle

Paula Chateauneuf, lute & renaissance guitar

Andrew Lawrence-King, Gothic harp, Spanish harp & psaltery

Produced and Engineered by Nicholas Parker

Recorded at West Dean College, nr. Chichester, Sussex

on November 10th-12th 1987

Throughout the Middle Ages the rulers of east-coast Spain — the

kings of Aragon and counts of Barcelona — had looked across the

Mediterranean and longed for a foothold in Italy. It was not, however,

until 1442 when Alfonso the Magnanimous (d. 1458) defeated Rene of

Anjou, his French rival for the kingdom of Naples, that such ambitions

were fulfilled. Alfonso transferred his court to Naples and it

automatically became a meeting-point for Hispanic and Italian culture;

and from this time, sometimes referred to as the Neapolitan 'Golden

Age', a tradition for musical exchange between Spain and Naples was

established that was to last for several centuries.

Documentary evidence shows that music, both sacred and secular, works

of musical theory, musical instruments as well as the singers and

instrumentalists themselves travelled back and forth across the

Mediterranean from the reign of Alfonso onwards. An important figure in

the transmission of musical repertory in this way was undoubtedly the

Spanish-born Johannes de Cornago who served both at the Neapolitan

court of Alfonso and his illegitimate son and heir Ferrante I (d.

1494), and at the Aragonese court of Ferdinand of Aragon (d. 1516) in

Spain. His name appears only once in the Aragonese treasury accounts

— in May 1475 — though the fact that the account books are

incomplete for this time makes it difficult to know whether this was a

fleeting visit or an extended sojourn. Either way Cornago's presence in

Spain would account for the inclusion of several of his songs in

manuscript sources closely associated with Ferdinand's court such as

the Cancionero Musical de Palacio.

At the same time, Cornago, or perhaps one of the several other Spanish

singers who served at both courts, would have brought with them some of

the Italian songs preserved in these sources, as well as works by

Josquin and Martini and other Franco-Flemish composers active in Italy.

For in addition to its Spanish connections, the Neapolitan court was in

constant contact with the courts of northern Italy such as Mantua and

Ferrara and the frottole of Cara and Tromboncino were certainly known

there.

Naples, then, was a veritable melting-pot for the musical repertory of

the late 15th century, and even though the splendour of the Neapolitan

court waned after the death of Ferrante in 1494, it continued to fulfil

this role. After a decade of internal strife and conflicting claims to

the Neapolitan crown, Naples fell once more in 1504 under Spanish

dominion so that cultural exchange with the east coast of Spain

continued to flourish well into the Renaissance. Ferdinand himself,

like his uncle Alfonso before him, seems at one point in 1506 to have

envisaged setting up his court in Naples and he stayed there for the

best part of a year. After his death in 1516, his second wife Germaine

de Foix married the Duke of Calabria and their court in Valencia

(traditionally the strongest point of contact with Naples) became one

of the most important musical centres in Spain in the first decades of

the 16th century.

Although little biographical information has come to light for the

vihuelist Luis de Milan, he was clearly closely connected with the

Valencian court for most of his career, and his El Cortesano of

1561 describes in detail the daily life of that court: the hunting, the

games and entertainments, the music-making and the social chit-chat of

a thoroughly renaissance court. Taking as its starting-point

Castiglione's Il Corteggiano, Milan's book bears witness to the

Italian influence that continued to reach Spain primarily via Naples

and that was felt more keenly in Valencia than in any other part of the

Iberian peninsular. The tradition for Spanish musicians making their

careers in Naples was also continued by Diego Ortiz who, born in Toledo

in about 1510, was certainly in Naples by 1553 when he published his Trattado

de glosas, and who served successive Spanish viceroys as maestro

de capilla.

It was perhaps above all in the realm of song that Hispanic and Italian

cultures coincided; in both countries a strong tradition for courtly

song in the vernacular evolved during the second half of the 15th

century, very probably from an existing tradition for improvised song

to a simple lute or vihuela accompaniment as opposed to the tenor-based

contrapuntalism of the Franco-Flemish chanson. The extent to

which these were shared or independent traditions is difficult to

ascertain, but it is clear that the Neapolitan court may have held a

key position in this respect. There are many musical parallels as well

as shared poetic structures between the main song forms of the period

— the frottola and the villancico — not least the infusion

of dance rhythms and the predominance of the melody in the upper part

of three-or four-voice songs supported by strongly directional

harmonies. These features are also to the fore in the villanescha

— a slightly later development of the frottola — of the

Neapolitan composer and organist Giovan Tomas di Maio, who is generally

credited with having evolved this genre. His first volume of

villaneschi was published in Venice in 1546.

©Tess Knighton 1989