medieval.org

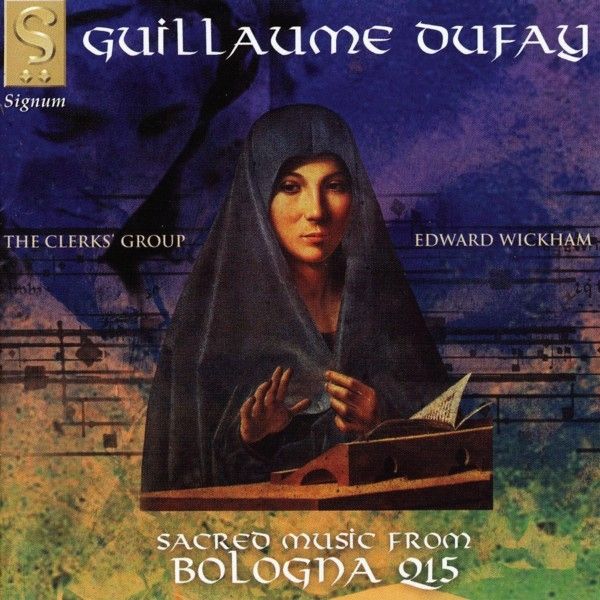

Signum Records SIGCD023

2002

1. Vasilissa, ergo gaude [2:46]

altos, tenor ChW, bass EW

2. Kyrie 'Fons bonitatis' [6:59]

tutti

3. O beate Sebastiane [2:59]

alto LB, tenors

4. Gloria · Bol. Q15 no. 107 [4:48]

altos, tenors

5. O gemma, lux et speculum [4:38]

altos, tenor MV, bass JA

6. Credo · Bol. Q15 no. 108 [6:30]

altos, tenors

7. Supremum est mortalibus bonum [6:26]

tutti

8. Sanctus and Benedictus · Bol. Q15 no. 104 [6:22]

tutti

9. Inclita stella maris [4:08]

altos, tenor ChW, bass JA

10. Agnus Dei · Bol. Q15 no. 105 [3:26]

tutti

11. Gloria 'Spiritus et alme' [6:04]

altos, tenors

12. O sancte Sebastiane [5:01]

altos, basses

The Clerks' Group

Edward Wickham

Alto: Lucy Ballard, William Missin

Tenor: Chris Watson, Matthew Vine

Bass: Edward Wickham, Jonathan Arnold

The Clerks' Group acknowledges with gratitude the help and advice

of Margaret Bent and Leofranc Holford-Strevens

Recorded in St Andrew's, West Wratting, August 31st to September 2nd 2000

by kind permission of the P.C.C.

Production, Engineering and Editing by Floating Earth

Producer: David Trendell Engineer: Limo Hearn

Editors: Raphaël Mouterde/Stephen Frost

Booklet notes: Edward Wickham

Text and translation editor: Christine Darby

Booklet design Sc typesetting: Jan Hart

Cover design: ATA Design

C 2002 The copyright of this CD booklet, notes, translations and visual design is owned by Sigum Records Ltd.

www.signumrecords.com

Guillaume Dufay. Sacred music from Bologna Q15

The manuscript Bologna, Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale, MS Q15 is

one of the great anthologies of 15th century music, without which our

understanding of early Renaissance music would be hopelessly impaired.

It is known as Q15 to its friends; and it has many friends, for

contained within it are examples of almost every conceivable musical

genre of the period—with a special emphasis on sacred

polyphony—and works by a vast array of composers. And even if we

choose to make a selection of works by a single composer, as we have

done here, the variety of forms and styles on offer is bewildering.

This is partly because Q15 does not represent a snapshot of musical

taste at one moment in time and at one place. Compiled in three stages,

over a period of approximately fifteen years and in various parts of

northern Italy, Q15 underwent a number of major revisions which reflect

changing attitudes and trends. Margaret Bent's dedicated scholarly

detective work on the manuscript has revealed how parts of the first

version of the manuscript were cut up and the paper re-used for the

second and third versions. By deciphering what the original manuscript

contained and comparing it to the final version, we can appreciate how,

in the space of fifteen years, musical sensibilities had altered. (See,

for example, Margaret Bent, ‘A contemporary perception of early

fifteenth-century style’ in Musica Disciplina 41 (1987)).

In our choice of works from Q15 by Guillaume Dufay, we hope to reflect

the diversity of genre contained within the manuscript as well as

presenting some of the earlier works—often neglected—of a

composer who witnessed and contributed to most of the revolutionary

changes to occur in music composition in the 15th century. On his

deathbed, Dufay was apparently comforted by the strains of his motet Ave

regina coelorum, but his earliest datable work—also labelled

a motet—is in an entirely different style, to the extent that one

might hardly recognise it as the work of the same composer. Vasilissa,

ergo gaude was written to celebrate the nuptials of Princess

Cleofe—part of the Malatesta clan for whom Dufay worked—and

Theodore Palaiologos II, the son of the Emperor of Constantinople. The

year was 1420 and while the rulers of Eastern Christianity were

desperately trying to shore up support from their Western

co-religionists against the Ottoman threat, the Western church was

involved in a council at Constance which aimed to resolve the

long-standing schism in Roman Catholicism. By the time of Dufay's

death, that schism would be resolved, but Constantinople would be in

the hands of the infidel.

Vasilissa inhabits a different musical world as well. Composed

in an isorhythmic format in which the rhythms of the second half of the

motet exactly repeat those in the first half, the motet celebrates the

techniques of the previous century as well as revealing a reverence for

another Northern European composer working in Italy, Johannes Ciconia.

The other three isorhythmic motets in this programme—O gemma,

lux et speculum, Supremum est mortalibus bonum and O

sancte Sebastiane—display varying degrees of enthusiasm for

the technique, but what is so impressive about Dufay's handling of

these predetermined structures is his ability to balance the

requirements of the form with the impulse to compose lyrical,

free-flowing tunes. Naive as it may sound in a discussion of

sophisticated sacred polyphony, Dufay is ever the supreme

melody-monger. His melodies may not always be held by a single voice:

in the four-voice works the top voices often playfully exchange roles,

one holding a coherent line while the other dances around it,

frequently decorating and ornamenting the material. But in all his

vocal polyphony there is a song-like quality to the writing which is

entirely distinctive and beguiling.

What has already been said should not encourage the view that Dufay

unquestioningly adopts the forms that he is given. Supremum est

mortalibus bonum, composed to commemorate the signing of a peace

treaty in 1433 between Pope Eugenius IV and King Sigismund (soon to be

Holy Roman Emperor), is a wonderfully eclectic creation, combining

isorhythm (in the tenor voice only) with solemn fauxbourdon and

declamatory homophony. In other works which are categorised as

‘motets’, Dufay abandons the isorhythrnic principle

altogether. O beate Sebastiane is written in a free form, with

a decorative upper voice accompanied by two lower voices with

supporting roles. Inclita stella maris is a particular

curiosity. The upper voices form a mensural canon: they sing the same

melody but at slightly different speeds. Again, the lower voices in

this work are unimportant and, according to the rubrics of the piece,

one of them can even be abandoned without impairment.

In fact, this is not uncommon amongst the works contained in Q15 and

other contemporary manuscripts. Extra contratenor parts were often

added or taken away from three and four part works, presumably

according to the taste and resources of the performers. Margaret Bent's

work on Q15 has revealed how the scribe's preferences in terms of three

and four part works changed, and it is generally—though not

always—the case that later transmissions of works present works

in four part versions. The Gloria and Credo pair included in this

programme are likely to be examples of three voice originals which have

had a fourth voice added, not always successfully. We cannot assume,

however, that the fourth voice was not also by Dufay and, in the

absence of any contrary evidence, we have recorded the four-voice

versions. These are lively settings, linked by some eccentric harmonic

twists in the opening ‘head motifs’ of each movement. As

with the Sanctus and Agnus movements, these mass movement settings

pre-date the time when the mass ordinary was routinely composed as a

cycle of linked movements, composers preferring to pair Gloria with

Credo, and Sanctus with Agnus Dei. Unrelated to other polyphonic

settings, the Kyrie Fons bonitatis is instead affiliated to the

chant now known in the Liber Usualis as Kyrie II. In our

performance we have interspersed this chant with the polyphony to

create a traditional nine-fold structure for the movement.

Notes on Performance

and Editions

The performing editions used in this recording take as a starting point

the musical and literary texts as transcribed and edited by Heinrich

Besseler in the Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae series. On

occasions these versions have been changed after consultation with

facsimiles of the manuscript Bologna Q15, while text underlay and

musica ficta have been substantially altered during the rehearsal

process. In particular, lower voices have been texted where possible

and appropriate, Inclita stela maris being the only work in

which the lower parts are entirely vocalised. We have thus rendered in

sound the speculative comments of David Fallows about this work in his

important study Dufay (London, 1982, p. 132).

I regret that the article by Leofranc Holford-Strevens on Dufay's

literary texts (in Early Music History, xvi—1997) did not

come to my attention until after the recording had been made. This

article suggests emendations to the texts of the motets which, though

having no substantial impact upon the aural experience of these works,

ought nevertheless to be incorporated in future editions and recordings

of these works. It is hoped that those who use CD booklets as part of

their research into these works will take note and not perpetuate these

mistakes in the future.

In line with the suggestions of Charles W. Fox and, more recently,

Timothy J. McGee (The Sound of Medieval Song, Oxford, 1998) we

have interpreted the signs which in modern notation indicate pauses, as

indications of the opportunity for ‘cantus coronatus’, or a

form of improvised decoration. This ornamentation is somewhat

experimental, but was influenced in part by the kind of ornamentation

which is to be found in Italian vocal music of the early Baroque and

which was presumably influenced by earlier Renaissance practice.

Edward Wickham, July 2001