Johannes REGIS. Opera omnia

The Clerks

medieval.org

classical.net

arkivmusic.com

musique en wallonie

Musique en Wallonie MEW 0848/9

2008

CD1

1. Celsitonantis ave genitrix ~ Abrahae fit promissio [7:21]

Missa Ecce ancilla Domini ~ Ne timeas Maria

2. Kyrie [4:29]

3. Gloria [7:46]

4. Credo [12:33]

5. Sanctus et Benedictus [10:09]

6.Agnus Dei [5:25]

Motets

7.Ave Maria virgo serena à 5 [7:33]

8.Ave Maria à 3 [2:27]

9. Lux solemnis ~ Repleti sunt omnes [10:14]

CD2

1. Clangat plebs [7:25]

Missa L'homme armé ~ Dum sacrum

mysterium

2. Kyrie [4:03]

3. Gloria [7:32]

4. Credo [7:44]

5. Sanctus et Benedictus [6:24]

6. Agnus Dei [4:04]

Motets et chansons

7. Lauda Syon salvatorem ~ Ego sum panis vivus [6:24]

8. Puisque ma damme ~ Je m'en voy [2:01]

9. S'il vous plaist [1:34]

10. Patrem vilayge [3:51]

11. O admirabile commercium ~ Verbum caro [7:34]

The Clerks

Edward Wickham

Carys Lane, Helen Neeves - soprano

Lucy Ballard, Ruth Massey - alto

Tom Raskin, Christopher Watson - ténor

Jonathan Arnold, Robert Macdonald, Edward Wickham - basse

Légendes des illustrations

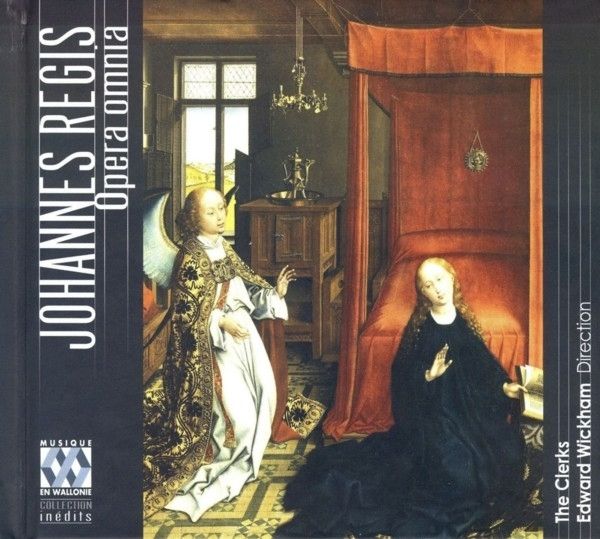

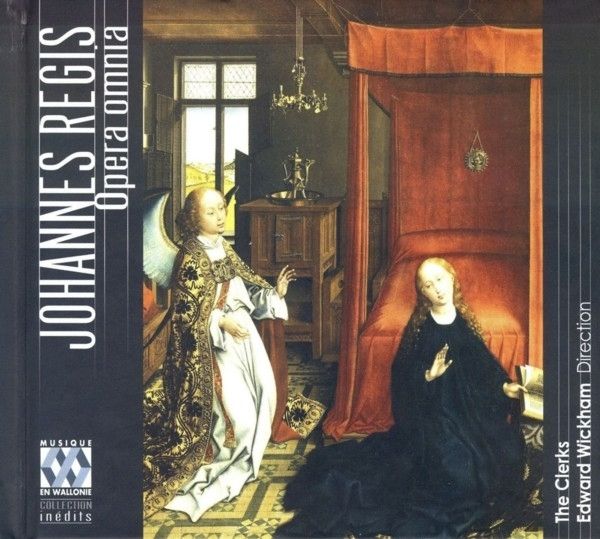

Couverture : Rogier van der Weyden (Rogier de la Pasture) (atelier), L'annonciation,

ca. 1440,

huile sur panneau de chêne, 0,86 x 0,93m, Paris,

Musée du Louvre (Inv. 1982), © RMN / Gérard Blot.

Notice :

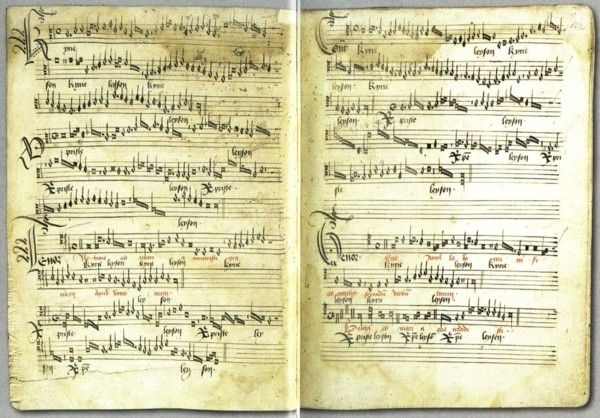

1. S'il vous plaist, Chansonnier de Jean de Montchenu

(chansonnier cordiforme), Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de

France, Rothschild 2973, f. 20v. et 21r.

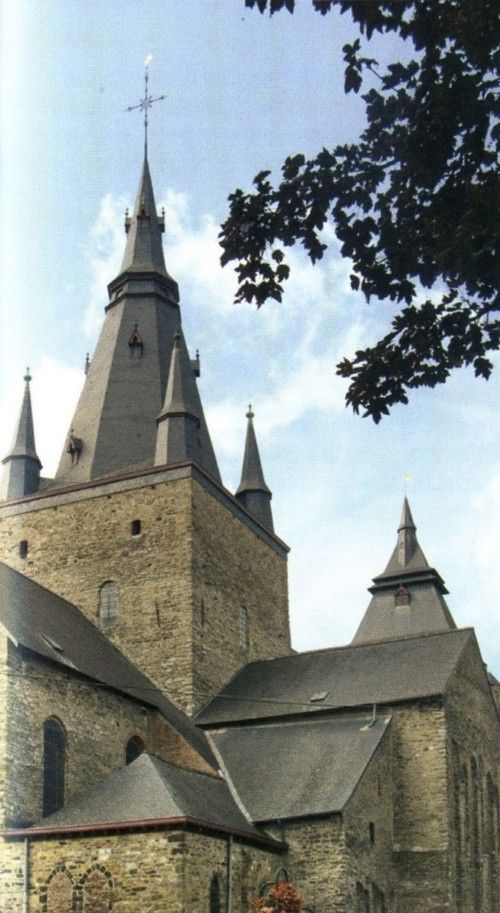

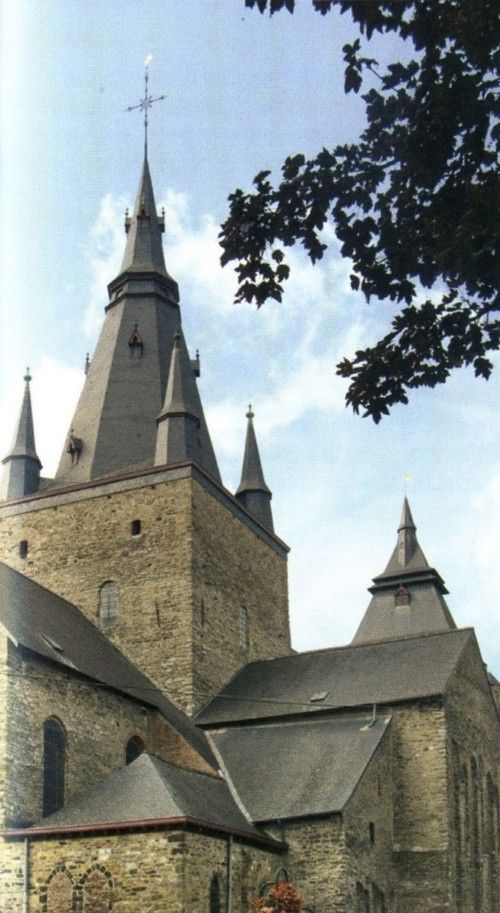

2. Collégiale Saint-Vincent de Soignies, © Gil

Bergeret, Commune de Soignies.

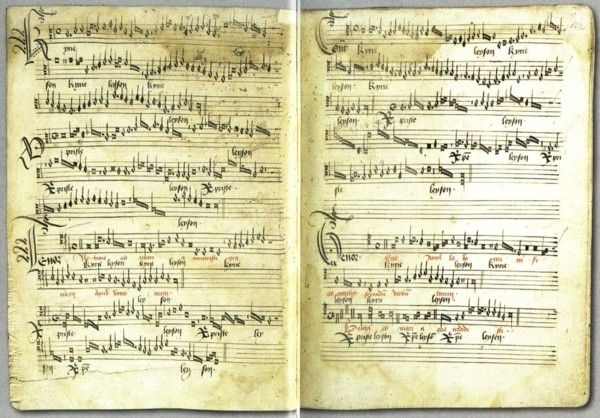

3. Missa Ecce ancilla Domini, Kyrie, Bruxelles,

Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Ms. 5557, f. 121v. et 122 r.

4. Clangat plebs, Rome, Bibliothèque apostolique

vaticane, Chigi C VIII, 234, f. 281v.

Remerciements

Édition préparée par Sean Gallagher et Jesse

Rodin, à l'exception de la plage 7 du CD 1

préparée par Theodore Dumitrescu.

Leofranc Holford-Strevens a édité les textes latins et

fourni les traductions anglaises des plages 1 et 9 du CD 1 et des

plages 1 et 11 du CD2.

The Clerks souhaite remercier ces érudits pour leur

collaboration à ce projet.

Nous remercions Madame Nadine Henrard pour la traduction des textes en

ancien français, CD 2, plages 8 et 9, et Monsieur Jean-Paul

Schyns pour la traduction des textes latins de la Missa Ecce

ancilla Domini et de la Missa L'homme armé.

Remerciements à Monsieur Goossens et à la

Bibliothèque royale de Belgique.

Production: Musique en Wallonie, ULg, quai Roosevelt 1B à 4000

Liège - Belgique (http://www.musiwall.ulg.ac.be/)

Enregistrement: 27 au 30 août 2007, Chapelle du collège

Sainte-Catherine, Cambridge

Prise de son et montage: Gemini Sound

Directeurs de projet: Philippe Vendrix et Christophe Pirenne

Graphisme: Valérian Larose

Réalisé avec le concours du Ministère de la

Communauté française de Belgique (Service

général des Arts de la scène - Service Musique)

JOHANNES REGIS.

Masses, motets and chansons

In a famous passage from his 1477 treatise on counterpoint, Johannes

Tinctoris noted the remarkable flourishing of musical composition in

his day and singled out five of his contemporaries for special praise :

Johannes Okeghem, Johannes Regis, Anthonius Busnoys, Firminus Caron,

and Guillermus Faugues... these men's works exhale such sweetness that,

in my opinion, they should be considered most worthy, not only for men

and heroes, but even for the immortal gods. Certainly I never listen to

them or study them without coming away more refreshed and wiser. Just

as Virgil took Homer as his model in his divine work, the Aeneid, so by

Hercules do I use these as models for my own small productions...

High praise indeed. Today two of these five, Ockeghem and Busnoys,

would still figure very high on anyone's list of fifteenth-century

composers. Outside of specialist circles, however, Regis, Caron and

Fougues remain little more than names. In itself this fact is

unsurprising; the history of music records no shortage of composers

much admired by contemporaries whose works have for various reasons

fallen by the wayside. But Tinctoris is a writer whose opinions should

be taken seriously. He was remarkably well informed about the music of

his time, quick to criticize what he did not like, and judging from the

citations found in his treatises, he had studied many of these

composers' works down to the most minute level of detail. If he

considered them to be of equal stature to Ockeghem and Busnoys, the

time is long overdue to at least give them another hearing.

Tinctoris cites Dunstaple, Binchois, and Du Fay, "all recently passed

from this life," as teachers of his five worthy composers. His

description may have been intended as a rhetorical flourish, but in the

case of Regis, many of whose works are recorded here for the first

time, there might well be some truth in the claim. Certainly he is the

only one of the five known to have had extended contact with both

Binchois and Du Fay. Regis is documented from 1451 as master of the

choristers at the collegiate church of St. Vincent in Soignies (in

Hainaut, diocese of Cambrai). Soignies was a musical center of some

importance, one with close ties to the Burgundian court. In 1453, after

many years of service in the Burgundian chapel, Binchois was himself

appointed by Duke Philip the Good to the provostship of St. Vincent,

where he remained until his death in 1460. He and Regis thus served in

the same chapter for most of the 1450s, in circumstances that would

have been conducive to some kind of teacher-student relationship: Regis

was still young, probably in his mid-twenties, while the much older

Binchois was by then one of the most renowned composers in Europe.

Just weeks after Binchois's death, Regis came into contact with Du Fay.

In November 1460 Regis was invited to take up the position of

choirmaster at the renowned Cambrai Cathedral. But he hesitated. Du

Fay, who was head of the musical establishment there, led long

negotiations over the next two years in an attempt to persuade him to

come, but in the end Regis stayed at Soignies. There he was named scholasticus,

a musical position at St. Vincent equivalent to that of cantor, which

he held until his death in 1496. But he remained in touch with Du Fay

throughout the 1460s and early 1470s, and following the older

composer's death in 1474 Regis founded an annual commemorative mass at

St. Vincent in his honour. The two composers clearly knew one another's

music : several of Regis's works were copied at Cambrai in the early

1460s, while Du Fay's music served as an important point of reference

for Regis.

Nowhere is his engagement with the music of Du Fay more apparent than

in his two surviving masses. His Missa Ecce ancilla Domini / Ne

timeas Maria and Du Fay's Missa Ecce ancilla Domini / Beata es

Maria both use the same rare version of the antiphon Ecce ancilla

and both are early examples of masses that employ more than one cantus

firmus, a practice that would become more common towards the end of

the century (especially in the masses of Obrecht). Regis actually

expands upon this aspect of Du Fay's mass. Whereas Du Fay limits

himself to just two Marian antiphons and presents them in alternation

in the tenor, Regis consistently combines his two main cantus firmi

and then adds five further antiphons, often transposed and in various

combinations. For all these similarities, the overall sound image of

Regis's mass differs considerably from that of Du Fay's, owing partly

to its frequent juxtaposition of the major and minor thirds above the

final. He favors a recurring melodic gesture in the superius that

descends to the final by way of subtle shifts between the major and

minor third, conveying at times a haunting sense of closure (as at the

very end of the mass). Elsewhere (as in the first sections of the Credo

and Sanctus) the effect is more harmonic in nature and the shift is

reversed, with minor giving way to major, broadening in pace and

opening into shimmering moments of near stasis.

Perhaps the most striking passage in the mass comes in the Credo: a

series of held sonorities at the words vivos et mortuos ("to

judge the living and the dead"). These may also provide a hint as to

the original function of the cycle. No other fifteenth-century mass

highlights this phrase in such a manner. The emphasis on "the living

and the dead" of a community of believers points to the environment of

a confraternity, one of the main functions of which was to aid the

souls of its deceased members. Given that both Regis's and Du Fay's Ecce

ancilla masses were included in the Burgundian choirbook Brussels,

Bibl. royale, MS 5557, we might seek their origins in that grandest of

confraternities, the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece, whose

meetings included the celebration of a Marian mass.

The Missa L'homme armé / Dum sacrum mysterium is if

anything even more impressive in its handling of multiple cantus firmi.

Here Regis explicitly links the image of "the armed man" with the

warrior archangel St. Michael by setting textual excerpts of the

Michael antiphon Dum sacrum mysterium to the famous L'homme

armé tune. This symbolic doubling of the "armed man" is even

embedded in the musical fabric: throughout much of the mass the melody

is presented in loosely canonic fashion in two voices (another

expansion on the practice of Du Fay, in whose own Missa L'homme

armé the cantus firmus is briefly set in canon). As

the cycle proceeds, the references to Michael multiply through the

introduction of five further melodies and / or texts from the saint's

Office. Regis sets certain of these texts in relief (e.g., the words Michael

praepositus paradisi in the Kyrie), allowing them to emerge clearly

from the surrounding mass text. His interest in coloring certain

sonorities through the frequent (at times startling) use of sharps and

flats is again much in evidence. But the effect is rather different

from the pungent cross-relations heard in his Ecce ancilla

mass. Here the brief motto that in various forms opens each of the five

movements has a surprisingly 'modem' sound in terms of its harmonies

(indeed the beginning of the Sanctus would not sound much out of place

in an early seventeenth-century liturgical work). The series of

sustained sonorities at the end of the Agnus Dei provides another good

example: there the 'deceptive' cadence deepens the sense of the cycle

as a whole coming to a close.

A "missa sus l'ome arme" by Regis was copied at Cambrai Cathedral in

M62, that is, near the end of the long negotiations to bring him there

as master of the choristers. This is in fact the earliest known

reference to any mass based on the L'homme armé tune. It

has been suggested Regis must have composed two L'homme armé

masses, the Dum sacrum mysterium mass and an earlier one,

now lost, to which this Cambrai document refers. However this now seems

unlikely to be the case. Recent research has revealed considerable

evidence for the Dum sacrum mysterium mass having been composed

for Cambrai Cathedral, specifically in connection with a service for

the feast of St. Michael founded in the late 1450s by Michel de

Beringhen, canon of the cathedral and longtime colleague of Du Fay.

Another work Regis may have composed for Cambrai is his Patrem

vilayge. More modest in scope than the Credos of the two cycles,

this work includes a paraphrase of the Credo I chant, principally in

the two inner voices. Its only manuscript source is one copied at

Cambrai a generation after Regis's death. All the other works in the

manuscript are by much younger composers, suggesting Regis's piece

might have been included because it had already long been in the

cathedral's collection of polyphony. A distinctive feature of the work

is its fairly extreme form of text telescoping, with as many as three

different phrases of the text being sung simultaneously (including the

surprising coincidence of the words Et resurrexit and Crucifixus!).

Regis's best known works during his lifetime were his five-voice

motets. Before about 1470 music in more than four voices was very rare,

and Regis's large-scale cantus firmus motets represent the

earliest sustained attempt to compose in five parts. The inclusion of

an 'extra' voice (offen set as a second low part beneath the tenor)

allowed him to explore his evident interest in textural contrasts and

sonorous effects of various kinds. Younger composers came to recognize

the potential of this Regis-type motet, and his works would later serve

as models for five-voice motets by Obrecht, Josquin, Weerbeke, and

others. Regis's precedence in five-voice composition is reflected in

Petrucci's Motetti a cinque, a collection published a dozen

years after the composer's death, which includes four of his motets

(more than any other composer represented), among them his Clangor

plebs flores / Sicut lilium, which opens the collection.

Thirty years before Petrucci, Tinctoris had cited Clangat plebs

as one of a handful of pieces that exemplified the theorist's

compositional ideal of varietas. The word can be interpreted in

different ways, but from Tinctoris's comments and the music he cites,

his aim was to highlight a mode of composing. Using a range of

techniques, contemporary composers could work out a sequence of musical

passages, each having its own localized sense of regularity and

coherence, the nature of which was continually changing. In the case of

Clangat plebs, Regis took a generic blueprint for a tenor motet

- with a division into two large sections (one in perfect time, the

other imperfect) and a liturgical cantus firmus set mostly in

longer note values in the middle of the texture - and gave it shape

partly by means of a near systematic shifting of voice groupings. The

technique is effective because it is so clearly audible, as at the

beginning of the motet's secunda pars ("Carmina condentem").

Short phrases regularly alternate between the two upper voices and all

five. The tenor then drops out, the duos become longer and move between

the upper and lower pairs of voices. With its return the tenor takes on

a new function, participating in a loose type of paired imitation. This

texture gives way in turn to four voices, then all five, with a third

and final statement of the tenor cantus firmus propelling the

work to its close.

Comparable techniques can be heard in all the motets, though it is

impressive how even among works sharing general features Regis is able

to give each a distinctive character. Lux solemnis / Repleti sunt

omnes, like Clangat plebs and Lauda Syon salvatorem /

Ego sum panis vivus, is a D-mode work with a low notated range (the

bassus in all three motets frequently descends to low D). But unlike

the other two works, which begin with the expected duos and trios, Lux

solemnis starts with a very full four-voice texture to which the

tenor is soon added, resulting in one of the most majestic opening

paragraphs in all fifteenth-century music. Elsewhere the motet is more

declamatory in tone, as in the emphatic culminating gestures at the

ends of its two partes, and especially at the series of verbs "imbuit,

illustrat, disponit", where the upper voice briefly takes on the

quality of a psalm recitation, enlivened by a pair of more active

voices below. In Lauda Syon salvatorem, the secunda pars

begins with an essentially homophonic presentation of beautifully

balanced phrases before moving on to other textural possibilities. Celsitonantis

ave genitrix / Abrahae fit promissio - a bright, G-mode motet

addressed to the Virgin Mary - contains passages shaped as much by

textual concerns as musical ones. Recurring gestures in the upper voice

capture a sense of "the angelic choir" as it "praises, cherishes, and

reveres" the Virgin, while at the end of the prima pars the

unexpectedly subdued scoring is apparently a response to "the sinful

soul that rejoices to have found through thee the entry to peace."

Three of the motets depart from his usual approach. O admirabile

commercium, memorably described by Reinhard Strohm as a 'huge

Christmas pie,' is the only of his motets with multiple cantus firmi,

among them the popular cantio Resonet in laudibus. This is his

most energetic work, as well as his most virtuosic, full of syncopated

rhythms and exuberant interjections. The five-voice Ave Maria..

.virgo serena sounds at first as if it might date from a generation

later than his other works. Gone is the long-note cantus firmus

in the tenor, replaced by a texture in which all voices are equally

active throughout, and the use of imitation is greater and more

consistent than in his other music. The similarity between its opening

phrase and that of Josquin's four-voice Ave Maria.. .virgo serena

has often been noted. Whether one served as model for the other, and if

so, which came first, are questions that may never be convincingly

answered, not least because the dating of Regis's motets remains

uncertain. That Regis was a full generation older than Josquin might

suggest the direction of influence, but cannot by itself confirm it.

What can be noted, however, is that on closer inspection Regis's piece

is not so very far removed from his other motets. Rather it is as if

the frequent textural contrasts and quasi-antiphonal voice pairings

found in the cantus firmus motets has here been streamlined and

regularized. Regis's little three-voice Ave Maria provides yet

another facet of his work. The texture is that of a chanson, and its

veiled, overlapping cadences and melodic sequences bring it closer to

Busnoys than any of Regis's other pieces. Even here, however, the

colors of certain harmonies recall his own grand motets.

The two chansons make one regret that not more of Regis's secular music

has survived. Both reveal novel twists on the conventions of

midfifteenth-century song. Much of S'il vous plaist utilizes

only pairs of voices, rather than all three, and so manages to be

texturally interesting even within such narrow constraints. Puisque

ma dame / Je m'en voy, for four voices, is a pristine example of

carefully gauged melodic contours, the simplicity of which makes its

unexpected accidentals all the more affecting.

The works recorded here make a persuasive case that Tinctoris was

justified in his high assessment of Regis. Their breadth of invention

reveal him to have been not merely a very skilled composer, but one of

the most distinctive and original voices of the period.

Sean GALLAGHER