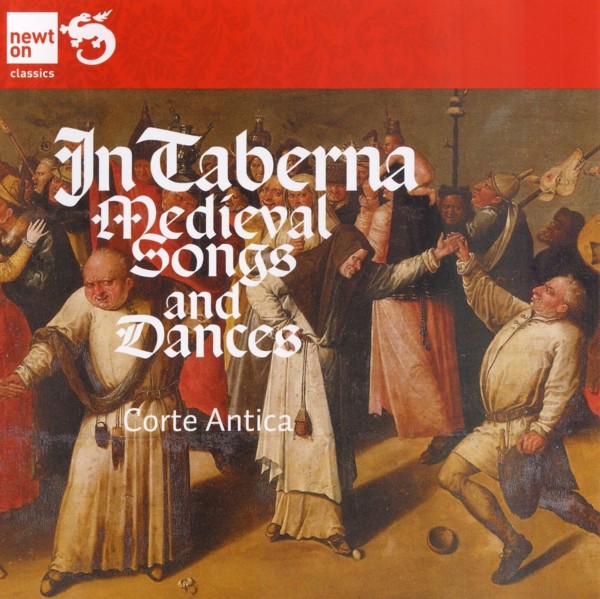

In Taberna. Medieval Passions

Medieval Songs and Dances / Corte Antica

medieval.org

Rivo Alto 2206, 2002

Newton Classics 8802126, 2012

1. Paduanus, 1308 [0:54]

Nicolò de' Rossi, 1290—c.1350

Anonymous

2. Tre fontane [1:23] 13th century

3. A l'entrada del tens clar [2:43] 13th century

4. VII Estampie royale [2:07] French dance, 14th century

5. Amor con un carcasso No.6, after 1470 [1:12]

Sonetti pavani del Codice Ottelio

6. Astra tenenti [2:35]

Ludus Danielis, 13th century

7. Kalenda Maya [2:40]

Raimbaut de VAQUEIRAS, 12th century

8. Ce fu un mai [3:16]

Moniot d'ARRAS, 13th century

9. Saltarello [1:49] Anonymous, 14th century

10. E vussi' rebaltar No.11 [1:28]

Sonetti pavani del Codice Ottelio

11. Conductus [1:34]

Ludus Danielis, 13th century

12. Ductia I [2:11] French dance, 13th century

13. Ja nuns hons pris [7:12]

RICHARD the LIONHEART, 1157—1199

14. Trotto [1:41] anonymous, 14th century

15. Frelo, el me vien No.2 [1:28]

Sonetti pavani del Codice Ottelio

16. In taberna [2:11]

Carmina burana, Codex latinus 4660, 14th century

CB 196

17. In may [3:05]

Colin MUSET, fl.1200—1250

18. Quen a festa [2:55] Cantigas de Sancta Maria, 13th century

CSM 195

19. Sonetus domini Elisei patavini No.9 [1:13]

Sonetti pavani del Codice Ottelio

Anonymous

20. Lamento di Tristano e ... [2:37] 14th century

21. ... rotta 1:00] 14th century

22. V Estampie royale [3:38] French dance, 14th century

Marsilio da Carrara, 1294—1328 and

Francesco di Vannozzo, c.1330—c.1389

23 Dominus Marsilius de Carraria ad, c.1360 [1:11]

24 Responso Francisci Vanocii [1:14]

Sonetti pavani del Codice Otellio

25. Paduanus quidam No.1 [1:24]

26. Antedicuts No.3 [1:16]

27. Si no se ne ha ben No.4 [1:15]

28. Villanesco No.5 [1:23]

29. Paduanus quidam 2 No.7 [1:08]

30. E fu in su No.8 [1:15]

31. Sonetus domini Helisey patavini No.10 [1:19]

Corte Antica

Mario Campagnaro — voice

Davide Carli — recorders, crumhorn, percussion

Angelo Di Prima — recorders, crumhorn, percussion

Arrigo Pietrobon — flutes, crumhorns, bombard, percussion

Claudio Sartorato — voice, hurdy-gurdy, percussion

Marco Squizzato — lute, percussion

Francesco Bisetto — narrator

Recording: 15-24 May 2000,

Palazzo Morello, Castelfranco Veneto (I)

Producer: Robert de Pieri

Balance engineers: Gianni Fantuz & Federico Xiccato

℗ 2002 Rivoalto

© 2012 Newton Classics B.V.

Manufactured and printed in the Netherlands

Thank you for buying this disc and thereby supporting all those

involved in the making of it. Please remember that this record and its

packaging are protected by copyright law. Please don't lend discs to

others to copy, give away illegal copies of discs, or use internet

services that promote the illegal distribution of copyright recordings.

Such actions threaten the livelihood of musicians and everyone else

involved in producing music. Applicable laws provide severe civil and

criminal penalties for the unauthorized reproduction, distribution and

digital transmission of copyright sound recordings.

ART DIRECTION & DESIGN

Jean Martin Wilschut BNO ICOM

Amsterdam Hotsprings

COVER IMAGE

Manner of Jheronimus Bosch

The Battle between Carnival and Lent (c.1600—1620), 74.7x240 cm, oil on panel

Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In Taberna: Medieval Passions

Laughter, derision, parody, jokes and satire: all 'tools for social

survival' (Éric Smadja). The comic, parodic and satirical poetry

presented on this CD provides, in performance, a thematic backdrop to a

rich feast of medieval music. While at its heart lies a group of

earthily humorous 15th-century sonnets in Paduan dialect — whose

local flavour is typical of folk tradition but whose literary qualities

are skilfully exploited — this collection of music, songs and

courtly dances can only be defined as European (in the sense that these

works are cross-cultural, rather than having anything to do with the

modern political entity). The shared experience of liberation from the

'tyranny of Latin' with the development of the vernacular Romance

languages centred first on the poetic heights of the French art, then

travelled the pilgrim and trade routes: from Celtic Ireland to Britain

and Flanders; from Germany to Provence; from the Spanish territories to

the courts of Italy. At this time, many of these routes converged in

the Po Valley: while the prospect of trading wealth drew some to Venice

(the Rialto, then one of the world's greatest marketplaces, is

mentioned in the first track on this album), others were attracted to

Padua as a seat of learning — its university was one of the

earliest to be founded (in 1222). The province of Padua was also home

to the court of the D'Este family, the Provençal troubadours'

first Italian port of call, and the place where Marchetto (da Padova)

codified, with the Ars Nova, the future development of polyphony.

During the long medieval period (the 5th to 15th centuries) music was a

fundamental part of people's everyday lives. Its role was essentially

functional, with pieces often improvised or composed for specific

occasions: to accompany work, battles, banquets, feast-days and other

celebrations. It owed much to the monodic Jewish chant tradition whose

influence spread to Europe with Christianization.

It was Charlemagne, meanwhile, who established musical performances at

court, with his love for accompanied songs telling of heroic feats

(there was at the time a ban on the liturgical use of instruments).

Travelling fairs carried music across borders, enabling a wide

circulation of both melodies and the Romance languages, as the

dominance of Latin began to wane. There was one entertaining exception

to the latter rule: the Italian students known as Goliards composed and

performed songs in an 'updated' Latin, setting texts often somewhat

lacking in sophistication (favourite themes being wine, women, sex and

general joie de vivre). Jongleurs were professional musicians

and entertainers, some of them performing to a high level — the

'jongleurs de geste', or singers of epic narrative verses. From the

higher echelons of society, where art and music were already highly

valued forms of diversion, came the troubadours (from Provence, writing

in the langue d'oc) and trouvères (from northern

France, writing in the langue d'oïl) — travelling

composer-poets who sang refined songs of chivalry and courtly love.

Thousands of troubadour and trouvère works survive, some

with musical notation intact.

In Germany, meanwhile, the Minnesänger represented the

homegrown equivalent of the troubadour/trouvère

tradition, incorporating local elements into the

Provençal/French genre of courtly love. Their star began to fade

at the end of the 13th century, when their art was taken up by the

Meistersinger: artisans and other city workers — men with no

connections to court life — who formed themselves into guilds,

composing and performing in accordance with a set of strict regulations.

One fascinating aspect of the secular music written between the Middle

Ages and the early Renaissance is the range of musical instruments

used. These were classified on the basis of the intensity of the sounds

they produced, thus were either haut (loud: used principally in

outdoor perfomances), or bas (soft: designed for church use).

On this album the instruments play and the voices sing, but the dances

are left to our imagination. Among them are French estampies,

interwoven with anonymous works and others by known authors, and with

new and evocative discoveries as well as 'classics' such as the extract

from the Carmina burana of Codex latinus 4660, or the brief

incursion into the non-secular repertoire represented by one of Alfonso

X's Galician-Portuguese Cantigas.

This Corte Antica performance conjures up an ideal crossroads at which

jongleurs and troubadours, nobles and minstrels, dancers and Goliards

meet — a place where people suffer heartbreak and laugh heartily,

drink fine wines and call lost loves to mind. Is this the Middle Ages?

It's certainly how we'd like to think of those far-off days...

Robert de Pieri

Translation: Susannah Howe