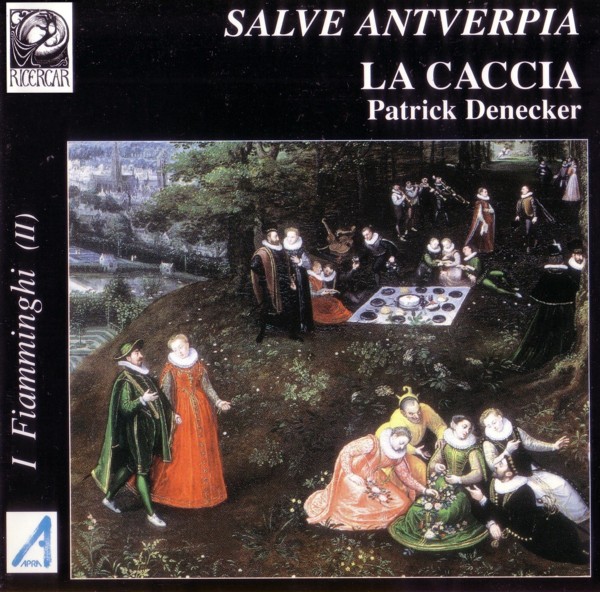

Salve Antverpia / La Caccia & Capilla Flamenca

Musiques jouées, chantées et imprimées à Anvers au cours du 16° s.

medieval.org

Ricercar 206 902

1999

Pierre PHALESE

1. Passamezzo d'Anvers [1:25]

alta capella

Jacobus CLEMENS non PAPA

2. Forbons [2:17]

alta capella

3. [5:38]

Tielman SUSATO

Pavane Si par souffrir

flûtes à bec

Pierre PHALESE

Gaillarde Si pour t' aymer

Gaillarde l'Esmerillonne

Gaillarde Puis que vivre

bassa capella

Ballo Milanese

flûtes à bec

Jacobus CLEMENS non PAPA

4. Justempus [1:36]

alta capella

Benedictus APPENZELLER

5. Se dire de l'osoie [1:50]

4 voix ATTB

6. Le printemps faict florir [2:23]

flüte à bec / luth

7. Viens tost [2:20]

4 voix ATTB

Pierre de MANCHICOURT

8. Pourquoy m'est tu tant ennemie [2:08]

flûtes à bec

Benedictus APPENZELLER

9. Gentils galants [1:14]

4 voix ATTB

Pierre PHALESE

10. [7:47]

Branle simple 1

alta capella

Branle Communs 5

flûtes à bec

Branle Communs 7

Hoboken dans

alta capella

Branle Gay 3 & 6

flûtes à bec

Branle simple 1

Branle Mon amy

Branle simple 1

alta capella

Emanuel ADRIAENSSEN

11. Fantasia prima [4:24]

luth

Pierre PHALESE

12. [2:52]

Allemande & Saltarello «Bruynsmedelyn»

Allemande & Saltarello «Poussinghe»

flûtes à bec

Lupus HELLINC

13. Nieuwe Almanack [1:27]

alta capella

Tielman SUSATO

14. [7:34]

Pavane «Mille Regretz»

flûtes à bec

Pavane «Mille ducats»

Gaillarde II, III

cromornes

Gaillarde I

alta capella

Pierre PHALESE

15. Schiarazula Marazula [1:24]

alta capella

Orlando di LASSO

16. Matonna mia cara [2:08]

4 voix ATTB

Emanuel ADRIAENSSEN

17. Allemande Nonette [1:40]

luth

Andreas PEVERNAGE

18. Ardo, Donna, per voi [2:52]

4 voix ATTB

Tielman SUSATO

19. [6:31]

Danse du Roy · Bergerette

alta capella

Le joly Bois

flûtes à bec (4')

Bergerette «Les grands douleurs»

alta capella

20. Salve quae roseo [8:41]

5 voix ATTTB

21. La Morisque [1:03]

alta capella

Pierre PHALESE

22. Passamezzo d'Anvers [1:31]

alta capella

Alta capella: groupement d'instruments à vent de plein air :

chalemie, bombarde(s), trombone(s), basson

Bassa capella: groupement d'instruments pour la musique d'intérieur :

ici, flûte à bec, luth et basson

LA CACCIA

Gunter CARLIER, trombone

Patrick DENECKER, flûte à bec, cromome, bombarde

Mirella RUIGROK, flûte a bec, cromome, basson

Elisabeth SCHOLLAERT, chalemie

Karl-Ernst SCHRÖDER, luth

Bernhard STILZ, flûte à bec, cromorne

Peter VAN HEYGHEN, flûte à bec, cromorne

Simen VAN MECHELEN, trombone

&

membres de la CAPILLA FLAMENCA:

Marnix DE CAT, altus

Jan CAALS, tenor

Stephane VAN DYCK, tenor

Lieven TERMONT, tenor

Dirk SNELLINGS, bassus

sous la direction de

Patrick DENECKER

Edition MUSIDISC Distribution

Enregistrement : Eglise St-Apollinaire à Bolland , Octobre 1998

Prise de son et direction artistique: Jérôme LEJEUNE

Deze opname werd gerealiseerd dankzij de welwillende steun van de verzekeringsgroep APRA

Cet enregistrement a été réalisé grâce au soutien du groupe d'assurances APRA

The Antwerp town players and singers.

Music played, sung and printed in Antwerp during the 16th century.

The

16th century was known as Antwerp's Golden Age thanks to a simultaneous

development of business, industry, art and science. The harbour town

became the most important warehouse of Western Europe; great numbers of

foreign traders and bankers made it their base, as did representatives

of all types of trade. The town's material wellbeing created a great

flowering of culture that was then encouraged by the town's rulers and

which in its turn attracted scholars and artists of all types to reside

in the city.

It is thus not surprising that secular instrumental

music, the music that was played by the town players and singers, also

underwent such an efflorescence.

The players and singers of

Antwerp had come together as members of the Guild of Saint Job by the

beginning of the 16th century and maintained their own chapel in the

church of Saint Jacob. The instrumentalists tried to protect their

professional interests by means of all kinds of rules and precepts, for

instance those dealing with musical ensembles and the teaching of music.

As the 16th century progressed, an innumerable quantity of players

streamed into wealthy Antwerp because the city offered so many

opportunities for employment. At every hour of the day there were

weddings, festivities and dances; the sounds of instruments being played

and of voices raised in song were everywhere, these also being mixed

with the happy bustling of the crowd, as the Italian author Ludovico

Guicciardini described in 1567. Above all, the Antwerp Guild of St. Job

offered the necessary corporate guarantees for all who made their living

from music. A small privileged group of players was that of the town

players, who gained status from playing music for the town councillors

wherever they went. They also were required to play the retreat or levee

in front of the town hall each evening and this turn was soon called “het lauweyt van de stadspijpers”; the pejorative meaning that came to be linked to the word lawaai

can clearly be blamed on the loud and out-of-tune playing of the town

pipers! They also performed in churches and in the town hall as well as

at all possible moments elsewhere, such as at visits from foreign

dignitaries, taking up of official positions as the swearing of oaths,

military successes of the reigning princely house, announcements of

peace, processions, annual fairs and all such occasions. In the 16th

century the Antwerp corps of town pipers consisted of five men; amongst

the instruments that they played were the shawm, the crumhom and the

trombone, to which they would add softer instruments such as the

recorder and the violin for indoor performances such as providing music

for banquets in the town hall. Any instruments could be used at any

given moment, but the most usual combination for performances outside

was that of three reed instruments and one trombone. We may well wonder

what the town musicians actually played, for in the sources that have

survived we read mainly of mottekens and liedekens. The

answer is actually very simple; the players performed anything and

everything that came to hand and that was suitable for the occasion.

This may be seen from the title-pages of the published books of songs

for several voices of the time, wherein we may often read “seer lustich om singen ende spelen op diversche instrumenten” or “accomodées aussi bien à la voix comme à tous instruments musicaux”.

It is clear that the vocal repertoire of the time was used not only in

settings for groups of instruments and voices together but also by

purely instrumental groups. We may further assume that the players gave

first preference to the immediately available publications from their

own local music presses.

The “vermaerde koopmansstadt Antwerpen”

reached the summit of its economic and cultural growth around 1540. By

this time it had grown into one of the most important Western European

centres for the printing of music, one where the most famed composers

had their works printed. Jehan Buys and Henry Loys were the first to

publish polyphonic music in the Low Countries with their 1542 edition of

Des chansons à quattre parties, composez par M. Benedictus. Their publishing house “In het Schaakspel”

was to be found in the Kammenstraat, where most of the printers and

booksellers of Antwerp had their offices. The composer Benedictus

Appenzeller, whose three songs Viens tost, Se dire je l'osoie and Gentils galans

are performed on this recording, was choir master to the Court Chapel

of Maria of Hungary, who was the regent of the Low Countries at that

time. Tielman Susato of Cologne, who began his career as a music copyist

in Antwerp, was virtually the first music publisher of the Low

Countries to adopt the new technique of movable type. He had possibly

drawn his inspiration from a collection entitled Selectissimae Cantiones

dated 1540, in which he had been able to include his own first

composition and which had been published in Augsburg by Melchior

Kriesstein. Susato was to publish more than twenty collections of songs

in total, the first ten appearing in the space of just two years. His

collection Le Second Livre des Chansons à quattre parties (1544) includes the song Pourquoy mest tu tant ennemie by Pierre de Manchicourt, the singing master of the church of St. Martin in Tours at that time.

Susato launched his series of volumes of motets in 1546 with the Liber Primus sacrarum cantionum quinque vocum; he included his own great motet of praise to Antwerp Salve quae roseo in the volume and this recording fittingly concludes with it. With the intention of “de hemelsche konst der musycken in onser nederlantscher moedertalen oock in 't licht te brengen”, he published Het ierste musykboexcken and Het tweetste musyckboexken in 1551. They contain for the most part anonymous four-part songs with Flemish texts, such as the song Lupus Hellinck's Nieuwe almanack,

both of which are recorded here. Hellinck was a singing master from

Bruges who composed this occasional piece for the festival of the Boy

Bishop on Holy Innocent's Day, writing probably for his own choir of the

Sint-Donaaskerk. Susato had been named town piper of Antwerp in 1531

and his shop on the Stadtswaag was fittingly called “In den kromhoorn”. His book of dances, Het derde musyckboexken

(1551) was regarded as being representative of the secular repertoire

of the Antwerp town musicians. These musicians were always being asked

by townspeople to perform above and beyond their civic duties at

countless weddings, banquets, dances and suchlike occasions, all of

these being moments for which the dance music that was published in

Antwerp was superbly fitting. Susato's third music book contains dances

for instruments in four-part arrangements, such as those for the Basse dansen, the Pavanes and the Gaillardes. The popular La Mourisque was danced by blacked-up boys with bells attached to their arms and legs.

As

well as the many printed collections there is also a great quantity of

music that has survived in manuscript form; such collections clearly

reflect the taste of the collector, as can be seen in the Lerma Codex.

This extensive collection contains pieces by 16th century Low Country,

Italian and Spanish composers and was assembled at the beginning of the

17th century by command of the Duke of Lerma, the minister of King

Philip III of Spain. From this collection we have included instrumental

versions of two compositions, Justempus and Forbons, by Jacob Clemens non Papa, the choirmaster of the Sint-Donaaskerk in Bruges.

Petrus Phalesius the Younger moved from Leuven to Antwerp in 1581 and took up residence in De Rode Leeuw

in the Kammenstraat. Together with printer Jan Bellerus he commenced a

series of editions with the intention of popularising the Italian

polyphonic style in the Low Countries. They published the Libro de villanelle, moresche et altri canzoni

together with youthful works by Lassus in 1582, the first printing of

which appeared a year later in Paris under the imprint of Le Roy &

Ballard. From this collection of villanelles we have selected the

popular four-part Matonna mia cara; this is better known as “The

Landsknecht's Serenade” and consists of a German soldier serenading his

beloved in broken Italian. Phalesius' firm created a number of

successful anthologies, including his Armonia celeste (1593) from which we have selected the madrigal Ardo donna per voi

by Andries Pevernage; the composer had been made singing master of the

Antwerp cathedral in 1585 and had assembled the above anthology himself

at Phalesius' request. Phalesius nevertheless remained interested in

instrumental music and the Antwerp book of dances Liber chorearum molliorum, otherwise known as the Recueil de danseries, rolled off his presses in 1583. From this collection we have chosen a number of Galliardes, Allemandes and Bransles, together with a Ballo milanese and a Hobokendans, whose titles indicate the use of local melodic material. We have also selected the original Schiarazula Marazula, whose mangled title possibly relates to the Commedia dell' Arte. This recording contains many times the Passomezzo d'Anvers,

into which an immediately recognisable tune has been worked and with

which the Antwerp town players would identify themselves in processions

in other towns.

With the publication of Emanuel Adriaenssen's Pratum musicum

in 1584, Phalesius the Younger continued a tradition of his father;

Petrus Phalesius the Elder has published a series of lute-books in

Leuven between the years 1545-1575. The Antwerp lute collection contains

mostly songs and dance tablatures, but in the guise of an introduction

also includes five fantasias in free fugato style — clearly compositions

by Adriaensen himself. From this collection we have chosen the Fantasia prima and the splendid Almande Nonette, in which the title and melody vent the complaint of a fair and life-loving girl who must enter a convent against her will.

Godelieve Spiessens

Translation: Peter Lockwood