Ave Mater, o Maria!, średniowiecne utwory marynje hiszpanii, francji, niemiec i polski

zespół muziki dawnej Dekameron early music ensemble

medieval.org

Dux 0129

2000

HISZPANIA · SPAIN · SPANIEN

ALFONSO EL SABIO (1223-1284). Cantigas de Santa Maria

1. Como Jesu Christo fezo a san Pedro [3:48]

CSM 369

sopran, fidel, tamburyn, chitarra morisca

2. Miragres fremosos [3:17]

CSM 37

sopran, fidel, darabuka, al oud

3. Todo logar mui ben pode sseer deffendudo [2:09]

CSM 28

fidel, bendir

4. Quen leixar Santa Maria por outra folia [3:19]

CSM 132

sopran, fidel, darabuka, al oud

5. Quen a Virgen ben servira [1:49]

CSM 103

sopran, fidel, bendir

FRANCJA · FRANCE · FRANKREICH

Motety · Motetes · Motetten

6. Aucun qui ne ~ Jure tuis laudibus ~ MARIA [2:19]

Kodeks Montpellier, XIII w. —

2 sopran, harfa

7. O Maria virgo Davitica ~ O Maria Maris Stella ~ VERITATEM [3:48]

Kodeks Montpellier, XIII w. —

2 sopran, harfa

8. O Maria Regine Glorie ~ Audi Pater ~ ALLELUYA [1:12]

Kodeks Bamberg, XIII w. —

2 sopran, harfa

NIEMCY · GERMANY · DEUTSCHLAND

Minnesäng

9. Salve Regina [4:12]

Reinmar von ZWETER, (ca. 1200-ca. 1260)

tenor, chrotta, rotta

10. Jesayas der Schrybet so [3:33]

FRAUENLOB, (1250-1318)

tenor, fidel, lutnia

11. Ich signe gerne [4:18]

NESTLER, XIII w.

tenor, chrotta

12. Maria, Muter [4:53]

Der MEISSNER, XVI w.

tenor, fidel, harfa

POLSKA · POLAND · POLEN

13. O gospodzie uwielbiona [1:45]

Rękopis Biblioteki Jagiellońskiej nr 2616 —

sopran, chór, 2 fidel, lutnia, harfa, symfonia

14. Virginem mire pulcritundis [2:24]

Rękopis Biblioteki Krasińskich, ca 1420 —

sopran, 2 fidel, lutnia

15. Ave Mater o Maria [1:43]

Rękopis Biblioteki Krasińskich, ca 1420 —

sopran, 2 fidel, lutnia

16. Ave Mater summi nati [3:14]

Rękopis Biblioteki Krasińskich, ca 1420 —

sopran, fidel, lutnia

17. Zdrowa bądź najświętsza królewno [6:10]

Rękopis praski, XV w. —

sopran, symfonia

18. Zdrowa bądź Maria [3:25]

Rękopis malborski, XV w.; Kancjonał Walentego z Brzozowa 1554 —

sopran, fidel, lutnia, harfa, symfonia

19. Ave hierarchia [1:12]

Graduał Tyniecki, 1526 —

sopran, psalterium

20. Bądź wiesiola Panno czysta [3:06]

Rękopis Biblioteki Raczyńskich, XV w. —

sopran, 2 fidel, lutnia

DEKAMERON, zespół muzika dawnej

Anna Mikołajczyk, sopran (1, 2, 4 - 8, 13 - 20)

Dorota Kozińska, sopran (6 - 8)

Jacek Wisłocki, tenor (9 - 13)

Małgorzata Feldgebel, fidel (1 - 5, 10, 12 -16, 18, 20); chrotta (9, 11)

Marzena Bajkowska, fidel (13 -15, 20)

Robert Siwak, tamburyn, tamburyn bearneński (1); bendir (3, 5); darabuka (2, 4);

Tadeusz Czechak, lutnia średniowieczna (10, 13 - 16, 18, 20); al oud (2, 4); chitarra morisca (1);

harfa (6 - 8, 12); rotta (9); symfonia (17); psalterium (19)

Gościnnie wystąpili / guest musicians:

Aldona Czechak, śpiew / vocal (13); symfonia (18)

Mirosław Feldgebel, śpiew / vocal (13); harfa (13, 18)

Małgorzata Polańska, symfonia (13)

Nagrania dokonano w

Kościół Wniebowzięcia Najświętszej Marii Panny w Warszawie w lisopadzie 1996r.

Recorded at the Assumption of the Virgin Mary Church un Warsaw, November 1996

Małgorzata Polańska, Lech Tołwiński: Reżyser nagrania /

Recording supervision & sound engineering

Krzysztof Gomoliński: Montaż cyfrowy / Digital editing

Antoni Dąbrowski, Anna Starowicz: Consultacja / Consultation

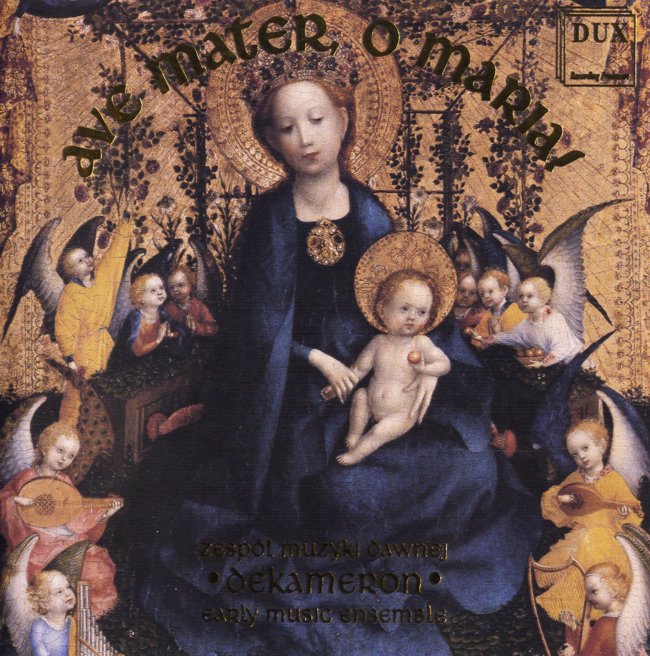

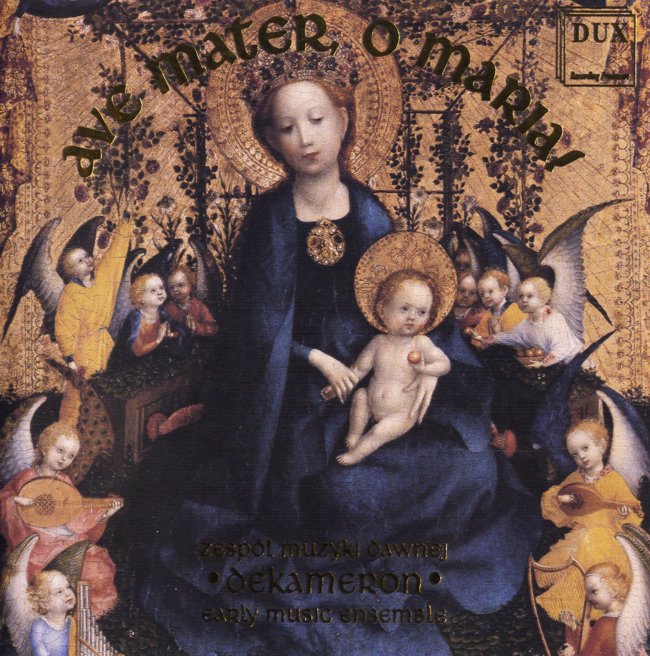

Stefan Lochner (1405/15-1451): Muttergottes in der Rosenlaube

Obraz na okładze. Własność / Cover. Courtesy of: Reinisches Bildarchiv, Köln

Piotr Konopka, Tomasz Sulejewski: Project graficzny, skład / Page layout & design

© DUX 2000

English liner notes

Kult Najświętszej Marii Panny towarzyszył cywilizacji chrześcijańskiej

od zarania, ale jego prawdziwy rozkwit w średniowiecznej Europie uważa

się za wynik działalności św. Bernarda, a potem św. Dominika. Począwszy

od XII stulecia stawiano ku czci Bożej Rodzicielki najokazalsze

świątynie, a wśród nich katedry Notre Dame w Paryżu, Chartres i Reims,

bazylikę opactwa benedyktyńskiego w Maria Laach, a także kościoły

Mariackie Krakowa, Torunia i Gdańska. W XIII wieku rozpoczął się wielki

ruch pielgrzymkowy do sanktuariów maryjnych w Montserat, Puy,

Rocamadour, Mariazell i do dziesiątków innych, rozsianych po calej

Europie miejsc, gdzie modlono się do cudownych obrazów i figur

Bogurodzicy. Madonna z Dzieciątkiem stanowiła ulubiony temat

średniowiecznej ikonografii. Początkowo przedstawiana była w pełnym

majestacie, najczęściej w otoczeniu wielbiących ją aniołów, lecz w miarę

upływu czasu jej wizerunki zaczęły tracić boskie dostojeństwo.

Zatroskana,

zamyślona bądź uśmiechnięta, emanująca ludzkim cieplem postać Matki

Boskiej, stała się szczególnie bliska ówczesnemu człowiekowi. Do Marii

zanoszono modlitwy o wyjednaniu u Boga najprzeróżniejszych łask, ku jej

chwale śpiewano pieśni, ona była bohaterką legend o cudownych

zdarzeniach. Do najpiękniejszych zbiorów poetycko-muzycznych opowieści

jej poświęconych, obok francuskich Miracles de Nostre-Dame Gautiera z Coincy z początków XIII wieku, należą kilkadziesiąt lat późniejsze kastylijskie Cantigas de Santa Maria.

Ich autorstwo przypisuje się królowi Alfonsowi X Mądremu, a wykonywane

byly przez śpiewaków oraz instrumentalistów licznie zatrudnionych na

dworze władcy. Cantigi, których treść nierzadko wywodziła się z ludowych

podań, traktowały min. o cudownych interwencjach Najświętszej Marii

Panny w sytuacjach beznadziejnych, a więc np. o tym, jak ratowała

złoczyńcę przed stryczkiem, uwiedzioną zakonnice przed hańbą,

zdesperowaną kobietę przed dzieciobójstwem... W owych opowieściach Matka

Boża zawsze okazywała miłosierdzie wobec grzeszników i pełną

wyrozumiałość dla ludzkich słabości.

We francuskiej twórczości

muzycznej XIII wieku wątek Maryjny pojawił się min. w motecie,

polifonicznej formie stanowiącej specjalność kompozytorów tego obszaru.

Każdy z głosów motetu opatrywano innymi słowami: tenor zazwyczaj

początkiem jakiegoś tekstu liturgicznego, natomiast pozostałe dwa glosy

albo tekstami zbliżonymi do siebie pod względem treści, albo też

zupełnie odmiennymi tak tematycznie, jak i językowo. Do utworów

pierwszego typu należy O Maria virgo Davitica / O Maria marls stella / Veritatem, gdzie zestawiono ze sobą dwa hymny pochwalne na cześć Matki Bożej. Przykładem drugiego rodzaju jest Aucun qui ne sevent / Jure tuis laudibus / Maria,

w którym łacińska poezja maryjna rozbrzmiewa jednocześnie z francuską

poezją miłosną. Owo Przenikanie się sfery sacrum i profanum wynika nie

tylko z wielotekstowością motetu, ale też z miejscowej tradycji

oddawania hołdu Najświętszej Marii Pannie. Trubadurzy i truwerzy

wysławiali ją niemal tymi samymi słowami, jakimi czcili damy swego

serca.

Francuska liryka posłużyła jako wzór minnesingerom, toteż

poczesna miejsce w ich twórczości zajmuje tematyka Maryjna. Niemieckie

pieśni ku czci Matki Bożej to nie tylko żarliwe modlitwy o osobistym

niemal charakterze, ale także swobodne adaptacje i parafrazy tekstów

liturgicznych. W Polsce utwory Maryjne - z Bogurodzicą na czele -

pojawiły się nieco później niż na zachodzie Europy i nie zawsze byly to

kompozycje oryginalne. Czasami zapożyczano je z repertuaru

"międzynarodowego", czego przykładem pochodząca z Włoch lauda Ave mater o Maria.

Powszechnie praktykowano przyswajanie kompozycji obcych poprzez

tłumaczenie ich łacińskich tekstów na język polski. Do takich przypadków

należy utwór Bądź wiesiola stanowiący rodzimą wersję

polifonicznego opracowania hymnu Gaude virgo. Niekiedy przekładowi

towarzyszyła jednak nowa melodia jak np. w pieśni O gospodzie uwielbiona, będąca translacją hymnu O gloriosa virginum.

Polski wkład do europejskiej spuścizny muzycznej stanowiły też

wielogłosowe opracowania popularnych śpiewów łacińskich, takich jak Ave hierarchia.

Muzyczna

podróż przez Europę ukazuje odmienność traktowania wątków Maryjnych

przez poszczególne nacje, ale jest także świadectwem uniwersalnej dla

średniowiecznych społeczeństw potrzeby wyrażania uwielbienia dla Bożej

Rodzicielki.

Agnieszka Leszczyńska

The

cult of the Blessed Virgin Mary has been part and parcel of Christian

civilization from its very birth. It began to flourish in medieval

Europe as the result of the activities of St. Bernard and, subsequently,

St. Dominic. From the 12th century onwards some of the most splendid

churches were built in praise of the Mother of God, including the

Cathedrals in Paris (Notre Dame), Chartres and Rheims, the Benedictine

Abbey in Maria Laach near Coblenz, as well as St. Mary's Churches in

Kraków, Toruń and Gdańsk. The 13th century saw the beginning of the

wideranging practice of pilgrimages to the Marian sanctuaries in

Montserrat, Puy, Rocamadour, Mariazell and dozens of other places across

Europe where prayers were said in front of the miraculous images and

figures of the Mother of God. The Madonna with Child was one of the

favourite subjects of medieval iconography. Initially she was presented

in full splendour, usually surrounded by angels in adoration. With the

passing of time, the images of the Madonna began to lose their divine

majesty.

The grieving, smiling or pensive Mother of God, now

emanating human warmth, became particularly close to man. People prayed

to Our Lady to intercede with God in granting them the required graces.

Songs were written extolling her glory. She was the heroine of numerous

legends about miraculous events. Among the most beautiful collections of

poetic and musical tales devoted to the Mother of God are the French Miracles de Nostre-Dame by Gautier of Coincy from the beginning of the 13th century and the Castillian Cantigas de Santa Maria.

The latter collection is said to have been compiled by Alfonso the

Wise, the King of Spain, around 1280. These religious songs were

performed by the sizeable complement of singers and instrumentalists

employed at the royal court. Many of the songs had a folk provenance and

spoke of the miraculous interventions of the Blessed Virgin Mary in

hopeless situations. And so, thanks to the Mother of God, a criminal was

spared imminent death at the gallows, a seduced nun did not fall from

grace and a despairing mother did not commit childmurder. In all the

songs, Our Lady showed mercy towards sinners and full understanding for

human weaknesses.

In the French music of the 13th century, the

Marian strand appeared, among other things, in the motet, the polyphonic

form in which French composers excelled. Each of the motet's voices was

assigned different words, the tenor usually sang the beginning of a

liturgical text whereas the remaining two voices were set to texts

either very similar or vastly different in content. O Maria virgo Davitica / O Maria mans stells/ Veritatem, in which two laudatory hymns in praise of the Mother of God are put side by side, belongs to the former type. Aucun qui ne sevent / Jure tuis laudibus / Maria,

in which Latin Marian poetry is put side by side with French love

poetry, is an example of the latter. The intertwining of the sacred and

the profane is also linked to the local tradition of paying homage to

the Blessed Virgin Mary. The troubadours and minstrels extolled her

virtues using almost the same words in which they addressed the ladies

of their heart. French lyric poetry served as a model for the

minnesingets, hence the Marian theme occupied an important place in

their work. German songs in praise of the Mother of God are not only

fervent prayers of a very intimate, personal character but also free

adaptations and paraphrases of liturgical texts.

In Poland, Marian songs, the best known of which was Bogurodzica

("Mother of God"), appeared a bit later than in Western Europe. Many of

them were Polish versions of songs from other nations, if only to

mention Ave mater o Maria imported from Italy. The adoption of foreign works by translating their Latin texts into Polish was common practice. Badź wiesiola (Rejoice Virgin), for instance, is the Polish polyphonic setting of the hymn Gaude virgo. In some cases, however, a Polish translation was assigned a new melody, as in the song O gospodzie uwielbiona (Glory to Thee) which was the Polish answer to the hymn O gloriosa virginum. The Polish contribution to European musical heritage also comprised polyphonic arrangements of popular Latin songs, such as Ave hierarchia.

This

musical journey through Europe demonstrates the diversity in the

treatment of Marian themes by various nations. It also vividly shows

that the expression of praise to the Mother of God was universal in

medieval societies.

Agnieszka Leszczynska

Translation: Michal Kubicki