‘Carmina

gallica’, French songs... For a man of the twenty-first century, the

literal translation of the title sounds quite modern, but the poems and

the music presented on our programme all date from between the late

eleventh and early thirteenth centuries. Most of the pieces are secular,

but a number of paraliturgical pieces have also been included, their

presence being justified by the fact that secular and religious poetry

at that time were very closely related. All the pieces are in Latin and

are the work of clerics: love-songs, songs of lamentation or jubilation,

narrative poems, dance songs, sequences, conductus... All these poems,

written in a language now dead, show an unexpected vitality and

freshness. Singing them almost eight hundred years later is for us the

best way to feel and understand a twelfth century that is so very far

removed from our own...

For a long time many histories of music

have assured us that the secular song came into being around 1100 with

Guillaume IX, the first known troubadour, and from then on rapidly

experienced great success. The birth of the song in the vernacular — in

this case, Occitan, the langue d'oc — was of major importance in

our artistic history. But we must beware of oversimplification, which

could lead us to overlook other factors that are just as crucial: for

example, the surprising amount of secular Latin poetry that was written

at the time of the earliest troubadours, and maybe even before. Before

1115 (i.e. during the lifetime of Guillaume IX) Heloise told Abelard

that young people all over France hummed his Latin love-songs (alas, all

lost).

As French historians, particularly over the past few

decades, have brilliantly shown, the period known as the Middle Ages

(contrary to the uniformity one might suppose from the term) was one of

great diversity and change. In all fields: not only economical,

political and social, but also cultural and artistic. In a range of

works, the French historian Georges Duby has played an important part in

shedding new light on the mentalities and sensibilities that prevailed

during different moments within the Middle Ages. Thus even within the

twelfth century, from which nearly all of the music presented on this

recording dates, there was a series of great changes. The poems of

Baudri de Bourgueil and Hildebert de Lavardin, the earliest pieces on

our programme with the anonymous song Jam dulcis amica, date from

a very specific period, during which the feudal system was at its

height (Dominique Barthélémy calls it ‘le paroxysme de la féodalité’).

From the beginning of the eleventh century, the king and the great

noblemen, at the same time as the pope and the bishops, saw their power

and authority considerably weakened. The minor nobility in the

provinces, often newly established, claimed new rights (the right to

build a castle, for example), introduced new practices in their favour,

and took the law into their own hands. The feudal system took hold all

over Western Europe, and throughout the eleventh century the nobility

amassed great wealth through the very high levies they imposed on the

farming world, which was then technically and demographically going

through a period of great progress. The high point of this feudal

movement, which was often violent and disorderly, came in the years

1070-1130. This period coincided exactly with the Gregorian Reform,

which the Church began to enforce at that time, although its major

effects — clear separation between the clergy and the laity, strict

supervision of private life by the Church (which nevertheless lost much

of its temporal power to the nobility), the crusading spirit, and the

development of the ascetic movement — were not really felt until during

the course of the twelfth century. Paradoxically, it was during that

same chaotic period that the world experienced ‘a new springtime’, as

Georges Duby calls it (‘un nouveau printemps du monde’), which grew and

‘flourished on the old Latin stock’. Indeed, Romanesque art gradually

developed in the monasteries of some of the French provinces far removed

from central power, monasteries which rapidly increased both in number

and influence. That time saw the triumph of Cluny and its amazing sway.

In those same abbeys, poetic and musical creation found new directions

in the form of tropes, polyphony, and liturgical dramas.

In a

world that appears to have been emerging from the dark ages, very few

people knew how to read and write. The artistic movements concerned only

a small elite at the greatest courts and within the episcopal or

monastic schools, where children of the nobility came for instruction.

At the end of the eleventh century, in the clerical milieux of the

cathedrals of the Loire Valley and neighbouring regions (Angers, Tours,

Rennes, Poitiers, Chartres), Latin poetry flourished. A number of

clerics, priests, and even bishops exchanged abundant correspondence and

wrote secular love-poems. This school of poetry very clearly prefigured

the birth not only of vernacular poetry, but also of courtly society.

In

the course of the twelfth century, the wind did indeed change.

Noblemen, kings and bishops managed to re-establish their power, using

the same methods as their vassals in the eleventh century: accumulation

of wealth through levies, strengthening of the feudal pyramid,

formalising of personal assets and inheritance, and so on. Royal Gothic

art was thus able to establish itself, under the impetus, first of all,

of Suger at Saint-Denis. The movement no longer came from the abbeys,

but from the cathedrals. Towns and their guilds also became more

powerful, soon representing the only strong opposition force to the

nobility. Art was secularised and urbanised and lyric poetry saw the

appearance of the first songs written in the vernacular, followed by

their unstoppable success.

But Latin was still extremely

versatile in the twelfth century. Indeed, for the intellectual elite,

the authors and composers of our ‘carmina’, it was much more than a

language of religion. Latin, which was constantly studied and used

throughout the Middle Ages, was spoken daily in the twelfth century by

that elite, which worked, invented, created and thought in Latin, and

completely renewed the poetic systems inherited from Antiquity.

Naturally, the lyric poetry of that century of strong contrasts

reflected the changes and upheavals of the time. The metrical system,

the alternation of long and short syllables that had governed classical

poetry since the Greek bards, was gradually replaced during the Early

Middle Ages by the rhythmic system, based on stressed and unstressed

syllables, which was more in keeping with reality, i.e. the everyday

language, as it was spoken and heard.

49 Likewise, rhyme and

assonance, and alliteration, which were quite rare until the tenth

century, came into general use, thus becoming characteristic features of

medieval poetry, with the more and more frequent use of the refrain.

The generation that formalised these fundamental innovations — that of

Abelard — was strongly aware of being ‘modern’ as opposed to the

ancients (indeed, the word ‘modern’ was coined at that time to mean just

that!). But it also recognised its debt towards the ancients through

the famous maxim of Bernard de Chartres: ‘Nous sommes des nains juchés

sur les épaules de géants’ (We are dwarves perched on the shoulders of

giants’). Abelard's generation clearly influenced and inspired all the

poets who came later in the century, particularly those represented on

this recording, including Hilaire d'Orléans, who was a pupil of Abelard,

and Pierre de Blois, whose tutor, John of Salisbury, was another of

Abelard's pupils.

Many parallels may be drawn between Latin

poetry and the repertoire of the troubadours and trouvères. They

appeared simultaneously and constantly enriched one another. In their

different languages, the poets innovated and experimented with new

literary forms, while remaining within a traditional framework. In both

cases, the manuscripts that have come down to us form only a small part

of the vast original corpus. The authors shared the same social

background, intellectually very rich and with a thorough knowledge of

ancient literature: although several of the troubadours were of more

humble origin, most of them were perfectly familiar with the Latin

repertoire; furthermore, some of them were themselves clerics. Both the

poems in Latin and those in the vernacular were meant to be sung (and

that was true until the fourteenth century!). In both cases, most of the

music has been lost: in a society in which the emphasis was on orality,

poets began to write down their works, but non-religious music was

rarely written down (the tunes were generally known to all, or could be

reused for several texts, since the practice of ‘contrafactum’ was

already attested in the twelfth century). Finally, as Jacques Chailley

has so brilliantly demonstrated, the poetic themes are often common to

both repertoires, and the formal, structural, literary and musical

similarities are striking: in both cases, great artists were busy

renewing the relationship between text and music, even though that

remained within the framework of established tradition, inspired by Ovid

and the great classical texts.

There is however one feature that

distinguishes the Latin poets of the twelfth century from their

counterparts writing in the vernacular: the sheer delight they take in

the skilful interplay of words. Their poems are light and clever,

showing extraordinary mastery of the language, its rhythms and its

colours. Pierre de Blois and Philippe le Chancelier, two poets from the

end of the century, provide some brilliant examples of such writing. And

their range was much wider than that of their predecessors: from sacred

conductus to erotic song for the first, and from settings of the simple, austere admonitio (admonition) to the flamboyant, lyrical lai for the second.

One

of the main difficulties for us, as musicians of the twenty-first

century, was to find a style of interpretation that would be fitting for

a period so remote from our own and so rich in musical genres. Like the

historians, we find ourselves faced with a major stumbling block: the

lack of sources. The earliest corpus of works by music theorists dealing

with interpretation dates from the thirteenth century and is devoted to

singing at the Cathedral of Notre Dame round about 1200. As Georges

Duby demonstrates, the social and cultural environment was very

different a hundred years earlier. The little we know for certain about

performance practice and the cultural mood of the period kept us within

narrow limits when it came to making our choices: the singing was

essentially for one voice, as was the instrumental accompaniment, when

it existed. It was essentially a monodic art, calling for no extra

drone, vocal descant or counterpoint — techniques that are generally

overexploited in modem interpretations. The mood must be intimate, and

almost elitist: we must imagine a court, a poet reciting his verses

before just a few people who were likely to appreciate the refinements

of his compositions. These were works by clerics, written for clerics or

for members of the highest nobility.

Such conditions are

obviously quite different from those one generally encounters in

concerts today. Furthermore, the musicians have to attempt to understand

the sensibilities of twelfth-century man, which were far removed from

our own. We discover, for example, that some beautiful melodies, very

similar in their serenity and fullness, can be used not only for fine

love-poems but also for amazingly fierce diatribes against the politics

of some important figure. How do we come to terms with this? And how are

we to interpret such intentions musically? Paul Rousset describes the

intense emotionalism, the extroversion, and the great inconstancy of men

of the Romanesque period. Material living conditions were terrible,

nature was hostile and unpredictable, and the cruelty of war took its

toll: it was a case of the survival of the strongest, who were often the

most violent. Moreover, the well-known violence of the knights echoed

the verbal violence of our poets. This ubiquitous violence coexisted

with a great sensitivity that was expressed unreservedly through tears.

Epic romances are full of such extrovert characters, easily touched by

physical beauty, capable of sudden switches from anger to tearful

desolation, and showing an immoderate taste for the marvellous, the

supernatural.

Research into ornamentation, i.e. finding the

necessary distance between the musical notation and the singer's

spontaneous rendering, also proves to be delicate (as it is for music of

the following centuries). A thorough knowledge of all related

repertoires, from before or after the twelfth century (notably Gregorian

music), is essential if we are to comprehend the musical language these

composers had at their disposal: typical modal formulas, cadences, etc.

The musician must then find the right balance between distance from the

written work, which was often non-existent in the twelfth century, and

respect for the sources which forms the basis of his work. Musicologists

underline the amazing stability of the oral tradition compared to the

uncertain ground of the written tradition (multiple variants,

misunderstanding, scribal errors, and so on). We have reduced the

musical instruments to a minimum: two medieval fiddles (vièles).

In northern France, especially after 1150, only the harp was suitable

for the accompaniment of these Latin songs, apart from the ever-present

fiddle. The lute family was excluded: it made its first timid appearance

in northern France in the thirteenth century. The instruments we use

are the result of extensive research on the part of instrument maker

Christian Rault, including a close examination of iconography and

statuary of the Romanesque period. There were clearly two different

types of medieval fiddle, based on harmonious mathematical proportions

and using various tunings that are found in many traditional music

repertoires throughout the world, as well as in the treatise written by

the Dominican Jerome of Moravia, who was the first musical theorist to

speak explicitly about the fiddle in the 1280s.

Finally, Diabolus

in Musica's approach to the reconstruction of early music always

involves great care with pronunciation. Research into the language seems

to us as vital as palaeographic examination of the manuscripts, if we

are to enjoy the full flavour — and power — of these poems. As

specialists in historical speech habits confirm (Gaston Zink, Eugène

Green), medieval clerics pronounced Latin using the phonetics they would

use for their vernacular mother tongue, while of course taking into

account the stress rules for medieval Latin. So this medieval Latin was

pronounced just like the French of northern France, the langue d'oïl,

which is described very precisely in many works on historical

phonetics, and its pronunciation evolved with the latter. On this

recording, the listener will therefore notice that we pronounce the

Latin not only with the nasalisations that are so typical of French, but

also with the French rather than the Italian ‘u’ sound, since that was

how it had been pronounced in northern France since Carolingian times.

It would have been a different matter if this music had been

specifically liturgical, for we know that papal envoys were often sent

to the French dioceses over the centuries with the responsibility of

ensuring that the orthodox (i.e. Italian) pronunciation was respected

(proof that it wasn't!). For our secular songs, in the courtly context

of this programme, ‘French’ pronunciation is necessary.

The songs:

PROMISSA MUNDO GAUDIA

by Hildebert de Lavardin is a poem full of symbolism about the Last

Judgement. The text, written in neo-classical Latin, nevertheless makes

use of the very musical process of the short two-word refrain, 'Die

ista' ('On this day'), forming a sort of litany.

The songs of Pierre de Blois:

this very great intellectual, one of the major figures of his century,

excelled in every aspect of literature, clerical or courtly, Latin or

vernacular. VITAM DUXI

is a discussion on the subject of love that one could imagine sung by a

trouvère at the court of Henry Plantagenet and his wife Eleanor.

Surprisingly it is found among the Latin conducti in the 'Magnus Liber' of the Notre Dame school (Florence manuscript)! SEVIT AURE SPIRITUS and SPOLIATUM FLORE,

which have contributed to the great renown of Pierre de Blois, are

almost erotic love-poems. Was his love fictitious, idealised? 'Flora',

the object of all the author's attentions, certainly appears to be a

human being made of flesh and blood... Pierre de Blois's love-poems

often include a joyful refrain. For this poet, love was a source of

happiness and enjoyment!

The rundelli:

clerical dances that were in favour in the late twelfth and early

thirteenth centuries in the north of France. They are found in the

Florence and Tours manuscripts. Evidence of profound and naïve faith,

they were performed by young clerics as amusement on the important feast

days. (Easter: PASSIONIS EMULI and MUNDI PRINCEPS; Christmas: LETO LETA CONCIO; celebration of a new bishop: O SEDES APOSTOLICA).

JAM DULCIS AMICA:

an anonymous love-song dating from the end of the eleventh century

(Jacques Chailley). It takes the form of a dialogue between two lovers,

but it lies on the edge of the secular and paraliturgical spheres: the

poetry is a sort of variation on the Song of Songs, inspired more by

Ovid than by courtly love, which was not yet in vogue at the time this

song was written!

The conducti of Philippe le Chancelier:

these songs are also taken from the Florence manuscript. Philippe

appears less light-hearted and more severe than Pierre de Blois, a fact

no doubt explained by his turbulent life, but his inventiveness is quite

striking. Philippe le Chancelier was a master of rhyme and literary

word play, a great poet and also an excellent composer and musician. His

qualities as a singer and player of the medieval fiddle (vièle)

were praised by the trouvère and cleric Henri d'Andeli. The pieces

presented here are excellent illustrations of Philippe's talents: a call

to order addressed to the Spirit, which must not allow itself to be

overrun by vanity (O MENS COGITA), a violent pamphlet against the baseness of the human condition and the weakness of the sinner (O LABILIS SORTIS),

a poem full of biblical references to the light Christianity brought to

the world, thus bringing to an end the 'old law' of Judaism (DUM MEDIUM).

GLORIA SI MUNDI: a planctus

by Baudri de Bourgueil on the death of Gui-Geoffroi, known as

Guillaume, eighth Duke of Aquitaine, father of the first troubadour,

which occurred in 1087 (William the Conqueror died the same year). The planctus,

a song of lamentation, was a very popular genre from the ninth century,

both in Latin and in the vernacular, and from the beginning musical

notation was provided. The planctus melodies seem to express very

unusual emotionalism, and we know the importance of the funeral rites

and ceremonies of feudal society, as of all so-called primitive

societies. The planctus is nevertheless more a song of

remembrance, a later tribute to the deceased, rather than music for the

funeral celebration itself.

SIC MEA FATA:

a love-song by Hilaire d'Orléans, for whom 'amor' rhymes so well with

'dolor'... The ambiguity of the text does not enable us to make out

whether the pleasure of loving outweighs the unhappiness of not being

loved, a theme that was very popular with contemporary troubadours.

Furthermore, this song is included in a manuscript from the south of

France (School of Saint-Martial of Limoges) containing many secular

Latin pieces, but also in the famous Carmina Burana manuscript, a

compilation offering a fine selection of lyric poems from the late

twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The anonymous conducti:

these pieces are taken from the famous 'Magnus Liber', now in Florence,

presenting the repertoire of the Notre Dame School of Paris as it was

in around 1200. The unique collection of monodic conducti

included in this manuscript gives us an incomparable view of late

twelfth-century Latin monody. None of the pieces bear a clear signature,

but many attributions are made possible by comparison with other

sources. The subjects, literary genres, and melodies show great

diversity and amazing scope, even though there are very few secular

love-songs in this manuscript written for the Cathedral of Notre Dame in

Paris.

O MARIA STELLA MARIS: a conductus

dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The Gothic period (from about 1140) saw

the extraordinary development of the Marian cult, accompanied by an

abundant production of literary and musical works. The last two lines

seem to be a refrain, but only one verse has come down to us.

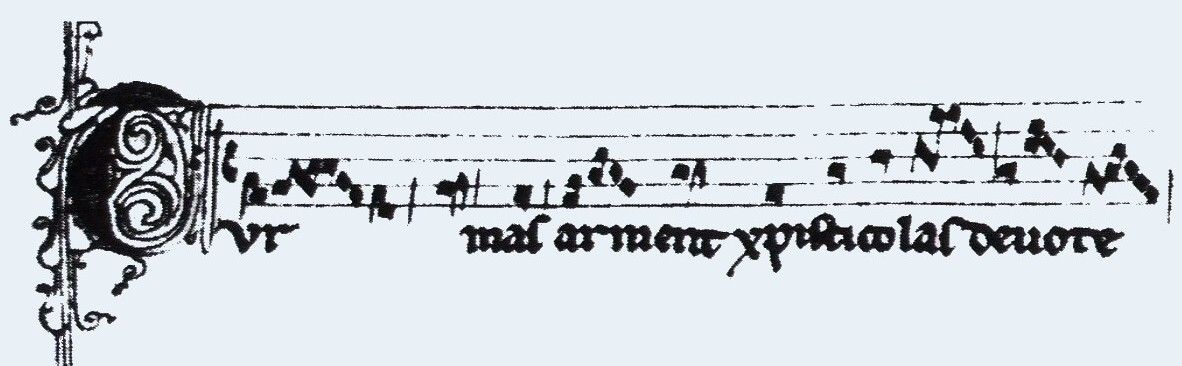

TURMAS ARMENT: a conductus

referring to a tragic event in clerical history: the murder in 1192 of

the Cardinal and Bishop of Liège, Albert de Louvain, by the henchmen of

Henry VI, who wished to set a man of his own lineage in the episcopal

see. The music for this occasional piece is very elaborate, with rich

use of melisma.

The prosae of Adam de Saint Victor: prosae,

or sequences, are rhythmic liturgical or paraliturgical poems. The

creative genius of the Middle Ages expressed itself with great

inventiveness in this genre. Paris was particularly active as a centre

for the composition of such pieces and the very recent but already

prestigious Abbey of Saint Victor, founded in 1108 by Guillaume de

Champeaux (by the middle of the century it already possessed one of the

largest libraries in Europe!) was highly reputed for its repertoire of

sequences and its own particular melodic traditions. Adam de Saint

Victor was undoubtedly one of the very great liturgical poets of the

Middle Ages. His poems are varied, flowing in style and very clear. The

symbolism he uses in his texts is obviously very similar to that of the

great intellectuals (Richard, Godefroy and Hugues de Saint Victor) who

ran the abbey school, which rapidly came to fame in the twelfth century.

We possess forty-five prosae by Adam; their very original melodies, using a wide range, remind us of the tunes used for the lais

(secular equivalents of the sequences). As with much Latin lyric poetry

of the twelfth century, the melody asserts its independence from the

text, and there is often a discrepancy between the musical stress and

the tonic accent in the language.

WHO's WHO:

Abelard:

born near Nantes around 1080, he died near Cluny in 1142, shortly after

being taken in by Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny. Abelard was one

of the greatest intellectuals of the whole of the medieval period. This

attractive, brilliant, and provocative man was a poet and theologian,

and a much-admired teacher. His multifarious talents quickly earned him

great fame all over Europe. His love affair with Heloise, his

intellectual (but nevertheless fierce) battles against St Bernard, but

also against most of the great minds of his time, his condemnation by

two Councils... are still famous to this day. His many love-songs,

apparently very popular, have unfortunately been lost. His literary and

intellectual influence was an enrichment to the whole of the twelfth

century.

Adam de Saint Victor:

we know very little about this poet, who was nevertheless very well

known in twelfth-century Paris. He was a high-ranking canon at the

Cathedral of Notre Dame until 1133, when he retired to the neighbouring

Abbey of Saint Victor, which he had long before made the beneficiary of

his income. That was no doubt the reason for the great tension that

existed between the cathedral and the monastery (which had nevertheless

been founded by a canon of Notre Dame). The quarrels came to a head with

the murder of the prior, Thomas de Saint Victor, who had been put in

charge of investigating the personal possessions of the archdeacons of

Notre Dame that same year (1133).

Baudri de Bourgueil:

born at Meung-sur-Loire in 1046; died in 1130 after being Prior of St

Pierre-de-Bourgueil and Archbishop of Dol in Brittany. He was one of the

pillars of the neo-classical Latin literary school that flourished in

the Loire Valley in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, but

his great fame was soon forgotten.

Hilaire d'Orléans

was an excellent Latin poet, close to the authors of some of the

Carmina Burana. He was Abelard's pupil at 'The Paraclete', originally

the great theologian's remote hermitage (near Troyes), which became a

school when pupils flocked to him, drawn by his renown.

Hildebert de Lavardin,

c1055—1133, Bishop of Le Mans, then Archbishop of Tours. He was noted

for his sermons, theological treatises, poems, and for an abundant and

very poetic correspondence with his ecclesiastical friends (including

Baudri de Bourgueil and Marbode de Rennes) in which he had no hesitation

in approaching the subject of secular love. Hildebert was a true

humanist, a lover of the beauties of this world and a great admirer of

Antiquity, a fact that was exceptional before 1100.

Philippe le Chancelier,

1165—1236, was a great man who led a tortured existence. As chancellor

of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, he was at the centre of a

violent quarrel between the bishopric and the emerging University of

Paris. All his life he fought against injustice, and he had no fear of

using his inventive and multifaceted literary talent for direct attacks

on the powerful men of this world. In Le Dit du Chancelier Philippe, the cleric Henri d'Andeli praised this 'minstrel of God' and his poems in the vernacular (unfortunately lost).

Pierre de Blois:

bom into an aristocratic family at Blois in 1135, this very great poet

died alone and destitute in 1212 after leading a very full life. He

studied at the universities of Tours, Paris and Bologna, was taught by

John of Salisbury, a pupil of Abelard, and was tutor in Palermo to the

future king of Sicily, William II, before joining the chancellery of the

most dazzling court in Europe, that of Henry II and Eleanor. This great

intellectual boasted of being capable, like Julius Caesar, of dictating

to four scribes simultaneously. His poems cover a wide variety of

genres: love-songs, erotic songs, occasional, moral or satirical pieces,

religious compositions, and debates. His œuvre is a perfect reflection of the aspirations, tensions and doubts of the twelfth century.

Antoine GUERBER

Translations: Mary Pardoe