On the Banks of the Seine. Music of the Trouvères

The Dufay Collective

medieval.org

Chandos 'New Direction' 9544

1997

1. Thibaut de CHAMPAGNE. J'aloie l'autrier [1:32]

dance | shawm, long trumpet

Guillaume d'AMIENS

2. Ses tres dous regars [1:14]

3. C'est la fins [1:29]

4. Prendés i garde [1:32]

Vivien Ellis, tutti (refrains)

5. Pucelete ~ Je languis ~ DOMINO [0:58]

6. On parole ~ A Paris ~ Frése nouvele [0:59]

voices G P W

7. Jehan BODEL. Les uns pins [4:03]

dance | 2 vielles, lute, recorder P, portative organ, symfony

8. Volex vous que je vous chant [3:18]

Vivien Ellis

9. La septieme estampie Real [2:58]

harp, lute, psaltery, gittern

Adam de la HALE

10. A Dieu commant amouretes [1:25]

11. A jointes mains vous proi [0:49]

12. Hé Dieus, quant verrai [0:43]

13. Tant con je vivrai [1:32]

14. Fines amouretes [2:26]

voices G P W

15. La douçours del tens novel [7:06]

Vivien Ellis, tutti (refrains), harp

16. La douçours [1:44]

dance | vielle, 2 recorders W P

17. En ung vergier [2:11]

2 bagpipes

18. Adam de la HALE. Dame or sui traïs [1:22]

voices G P W

19. Chanter voel par grant amour [3:52]

Vivien Ellis

20. Quant voi la flor nouvele [1:47]

flute, vielle G

21. L'autre jour par un matin [1:49]

22. Amor potest [1:29]

3 recorders

23. Adam de la HALE. Dieus soit en cheste maison [2:02]

voices G P W

24. MONIOT de Paris. Je chevauchoie l'autrier [4:29]

Vivien Ellis, vielle G

25. Je chevauchoie l'autrier [4:17]

dance | 2 vielles, lute, harp, psaltery, symfony

THE DUFAY COLLECTIVE

P — Paul Bevan, long trumpet, recorder, psaltery, voice

G — Giles Lewin, vielle, gittern, recorder, bagpipes, voice

W — William Lyons, flute, recorder, shawm, bagpipes, symfony, voice

Susanna Pell, vielle

Peter Skuce, harp, portative organ

with

Vivien Ellis, soprano voice

Jacob Heringman, lute

The Dufay Collective

was formed in 1987 to explore the wealth of music from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Sell-out performances in London's concert halls and major festivals throughout Europe, Russia, Hong Kong,

Australia, the USA, South America and the Middle East have established the group as one of Europe's

finest early music ensembles. They have also made numerous radio, film and television appearances.

The Dufay Collective aims to present concerts that are both informative and innovative,

recreating the variety of instrumental and vocal styles heard throughout this rich and colourful age.

The individual members' versatility and virtuosity has won critical acclaim and the enthusiasm

of audiences worldwide.

INSTRUMENTS

· vielles — James Bisgood, 1982 / Gary Bridgewood, 1988

· lute — Daniel Larson, 1996

· gittern — Tom Eve, 1980

· psaltery — Colin Booth, 1975

· harp — Tim Hoborough, 1993

· simfony — Samuel Palmer, 1980

· shawm — Linsey Pollack, 1991

· bagpipes — Josť Reboredo, 1993; Bill O'Toole, 1975

· trumpet — Nicholas Perry, 1993

· recorders — Moeck, Germany, 1978, 1980, 1987

· flute — traditional India

· portative organ Maunders, London, 1980

sources:

#1, 8, 20, 24 — Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, 5198

[1 reconstructed, MS Wallony II, No. 572.945 f142v]

#2-4 — Rome, Bibliotheca Vaticana 1490

#5, 6, 21, 22 — Montpellier Codex

#7 — fragment "Chanson de sabor" col. ess. Co 28; hq/Blackshaw 26

#9 — F-Pn fr. 844 f.104v

#10-14, 18, 23 — PBN fr25566 f33r-34r

#15, 17 — PBN fr.20050 f58v-f59r/65v-66r

#16, 25 — [fragment], L'eglise France [wins.] 311256 f40v

#19 — Paris, Arsenal 3517, f147r

Producer, Adrian Hunter

Sound engineer, Nicholas Parker

Assistant engineer, Richard Smoker

Editor, Ben Connellan

Recording venue, Oxford Church; 1—3 October 1996

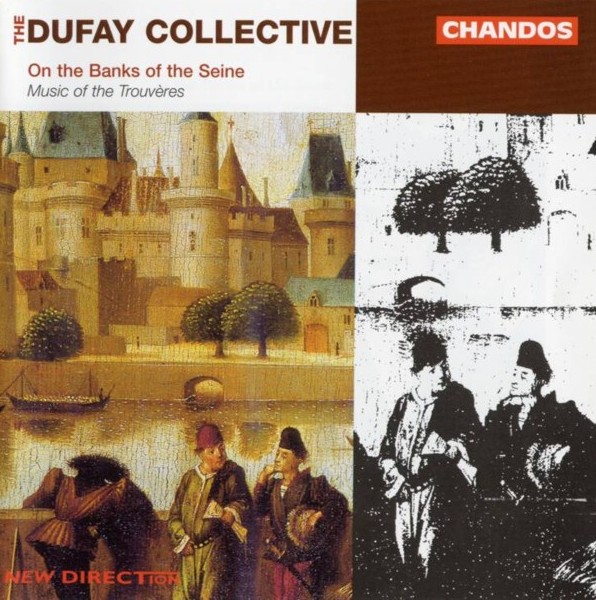

Front cover: Detail from Retable du Parlement de Paris, milieu du XVe siècle

(Réunion des musées nationaux, France)

Desing, Penny Lee

Booklet typeset by Dave Partridge

Ⓟ 1997 Chandos Records Ltd

© 1997 Chandos Records Ltd

Chandos Records Ltd, Colchester, Essex, England

On the Banks of the Seine

The

name 'trouvère' is largely used to define those poets and musicians who

lived, worked and wrote in the northern part of France during roughly

the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries. No single language united the

many poets and composers, rather there was a series of local dialects

from Champagne, Picardy, Normandy and England. Like their southern

counterparts, the 'troubadours', the trouvères came from diverse social

backgrounds, from the sons of weavers to noble kings. These poets were

steeped in the courtly poetic tradition in much the same way as the

troubadours, and their notion of fine amours (refined love) was discernible as that of the fin amors of the southern poets.

Poetic

genres were also common to both. Of the 2100 poems, mostly with music,

that survive in the great trouvère chansonniers, the pastourelle (pastorela) is particularly well represented, as is the jeu parti (joc parti). The sirventes seems however to have fallen out of fashion, and a new form, that of the chanson avec refrain appears popular among the northern poets. The chanson pieuse (devotional song) was common, and the chanson de recontre (knight meets lady) similar in both cultures.

The

jewel of trouvère culture was the burgeoning city of Paris, whose

university and Cathedral of Notre Dame were to define and shape musical

philosophy and development for the whole of Europe in the Middle Ages.

By

the mid-thirteenth century Paris was at the peak of its cultural

influence in Europe. The University was expanding, physically and

aesthetically, embracing wider disciplines, and in the new Cathedral of

Notre Dame the development of polyphony as a grand device for use in

Mass and Office proper was gradually, through the expansion of conductus

and clausulae, moving into the secular world with the composition of

the first secular motets in the vernacular. In the University, music

theorists benefited from such a stimulating environment, producing some

of the most significant writers on music of the Middle Ages: Jerome of

Moravia, Johannes de Grocheo, Johannes de Garlandia, Franco of Cologne,

Anonymous IV and Jacques de Liège.

The fact that such flourishing

centres of learning were situated in an equally thriving urban setting

could not be ignored. As humanist philosophy gained favour in the

University, and with the secularization of some of the academic posts,

so attention to the real world of city life grew. Grocheo in his De Musica

gives a unique view of the sociological aspects of Parisian musical

life, and by examining sermons preached in this period we see the Church

slowly being forced to accept secular entertainment, and even attempt

to justify it from a theological basis. Faced with an environment of a

well-populated city full of every vice under the sun, clergymen began to

find positive reasons for such vices as dancing and itinerant

minstrelsy.

As well as the courtly poet musicians, there were the 'professional' minstrels, or jongleurs

who would frequent in large numbers a city such as Paris, where regular

employment was to be had. It was the sight of these importuning

boasters hawking their talents that so appalled the sermonizers. Fierce

competition meant the itinerant jongleur would have to adopt 'hard-sell'

tactics - advertising his ability to be versatile on any number of

instruments, and his talents as a singer, dancer and juggler. Minstrels,

like trouvères could also come from diverse backgrounds. In an

intriguing reminiscence on life in Paris circa 1200, the theologian and

chronicler Jacques de Vitry tells of a student who desires to become a

jongleur 'thrusting himself up to others and refusing to do proper

work'. Such an educated man may well have been versed in reading musical

notation, been a trained singer and even have some knowledge of the

composition and performance of polyphony.

However exceptional

this anecdote may have been, it appears that by the late thirteenth

century urban musicians were beginning to feel the need to organize

themselves and regulate their activities. Street names in

thirteenth-century Paris attest to the fact that there were defined

areas where musicians could be located and hired, 'Vicus Viellatorum',

'Vicus Joculatorum' and most importantly the 'Rue des Menestrels' or

'Rue aus Jongleurs'. This latter was the street whose inhabitants drew

up a statute of eleven articles in 1321 for ratification of their

profession and for 'the common profit of the city of Paris'. This list

of eleven rules for musicians intending to work in Paris contradicts

some of the accepted behaviour of the minstrel. For instance, it is

ruled in statute five that:

No apprentice minstrel who goes to a

tavern may advertise himself or any other minstrel, nor make any mention

of his trade or praise it...

Other statutes demand:

No trumpeters or other minstrels may leave a feast before it is finished.

And:

A minstrel who has been hired may not send a deputy except in the case of sickness,

imprisonment or other necessity.

Suddenly

there is a code of practice for those previously classed as

unscrupulous vagabonds - entirely appropriate in an environment crowded

with able performers seeking to earn their crust.

In courtly settings the chansons

of the trouvères would most likely have been performed without the

accompaniment of an instrument, or with one vielle or harp, played

either by the performer or a jongleur. Songs such as the pastourelle

would most likely have been performed rhythmically. The polyphonic

rondeaux of Adam de la Hale and the motet repertoire have been

considered until recently to have been the intellectual entertainment

for 'learned men'. This exclusivity has now been brought into question,

justifiably so, considering the straightforward nature of the texts (of

the rondeaux), and the fact that like Vitry's jongleur student, minstrels could easily come from a literate background.

Dance

music for courtly settings would have consisted largely of an

improvised or aurally transmitted corpus of tunes. The courtly dance par excellence of the Middle Ages, the estampie would most likely have been common, played on the bas instruments: vielles, harps, lutes and gitterns. When outdoors, the louder (haut)

instruments (shawms, bagpipes and even trumpet) would possibly have

performed dances based on popular tunes. For the great social dance of

the city, the carole, stringed or wind instruments seem to have

been used, or, as commonly depicted, the song and refrains were led by a

female, with responses by the other circling dancers.

Some talk of threshing and winnowing,

And digging and labouring.

But these joys

Aren't my delight;

For there's no life

Like being in comfort,

With good clear wine and capons,

And being with good companions,

Merry and rollicking,

Singing and joking and amorous,

And having all you need

To pleasure

Fair ladies to your heart's content.

And all this you find in Paris.

(from the motet On parale / A Paris / Frése nouvele)

William Lyons © 1997 The Dufay Collective