On Friday 19 January 1526 an incident occurred that caused a certain

amount of upheaval in the city of Leiden. The sacristan of the

Pieterskerk found four highly abusive notes posted on the doors of the

church and on the confessional boxes. The contents of these letters

mocked the idea of confession and the not particularly pious way of

life of several members of holy orders there. These epigrams did not,

however, disturb the city fathers unduly, as there was as yet no

question of a powerful reformation movement at that time in Leiden. The

letters were nonetheless taken as a sign of the growing opposition to

the abuses prevalent within the Roman Catholic Church at that time. The

first vehement expression of this opposition that would eventually

result in a transition to Protestantism was the Beeldenstorm or

iconoclastic fury of 1566 that erupted in Leiden on 25 and 26 August of

that year. Disturbed by reports coming from other cities, the

burgomasters of Leiden had arranged a meeting on Sunday 25 August; this

meeting was interrupted by the sacristan of the Pieterskerk with the

news that several people who clearly intended to cause trouble had

forced their way into the church. On their arrival at the Pieterskerk

the burgomasters and pensionaries found two people destroying statues.

The culprits were driven out of the church and the sacristans of the

three churches in Leiden were ordered to keep the doors of the churches

closed. The Leiden militia were organised to guard the churches.

Despite these precautions, the iconoclasts broke into the

Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk on the night of 25-26 August; the Pieterskerk

also fell prey to the crowds later the following day. Altars were

desecrated and the marble statues of the twelve apostles that stood on

the pilasters of the choir were destroyed. The iconoclasts were not

able to break down the door of the sacristy, with the result that the

monstrance and other church property were able to be taken into

safekeeping the next morning. When the uproar quietened down on 27

August, the authorities took stock of events: The populace were told

that they would be severely punished if everything that had been seized

or removed from the churches and cloisters was not surrendered and

delivered to the St. Jacobsgasthuis; it was also announced that any

further violence against members of religious orders or their

institutions would be punished with hanging. The three parish churches

were cleaned and put in order so that normal religious observances

could be resumed.

Amongst the most important pieces of church property that survived

these two turbulent days in 1566 were the choirbooks of the College of

the Seven Liturgical Hours of the Pieterskerk. Their survival of the

iconoclastic fury seems to indicate that the manuscripts were carefully

kept somewhere under lock and key in the church. Today, these

choirbooks provide unique and extremely valuable proof of the rich

musical life of 16th-century Holland. Even though musical practice

flourished greatly in Dutch churches in 16th century, extremely little

evidence of this has survived in Dutch archives and libraries. Of the

countless music manuscripts that were used by singers of the liturgical

hours as well as others, only a fraction of these have survived the

ravages of time.

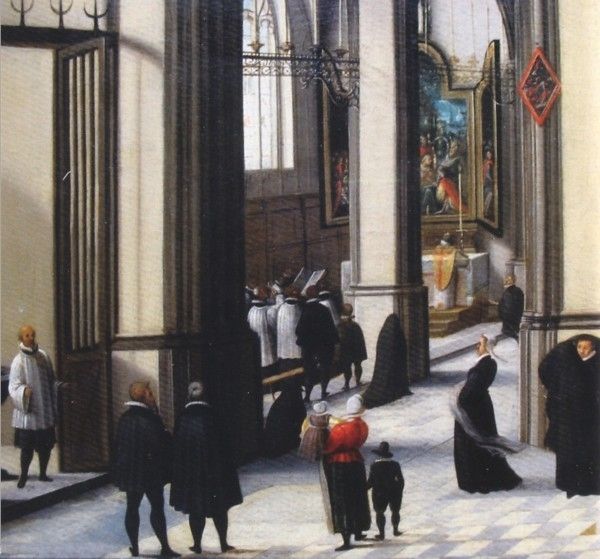

But who were these 'singers of the liturgical hours' and what precisely

was the function of a College of the Seven Liturgical Hours? For an

answer to this question we have to turn our attention to the city of

Leiden in the 15th century. The Pieterskerk was situated in the largest

parish of Leiden: according to a report by its pastor, it counted no

less than 5000 communicants in 1514. The Pancraskerk, Leiden's second

church, followed close behind with approximately 4000 communicants,

whilst the third, the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk, stood far behind with only

some 500 communicants. There was enormous and continuous activity in

the churches: altars were placed from the choir as far back as the

tower and a selection of clergy celebrated Mass at all of them. These

were primarily the pastor and his colleagues, of course, although there

were numerous other clergy occupied there as well. The memoriemeesters

— the administrators of the funds paid to the church for services

for the Dead — of the Pieterskerk employed thirty-four curates

between the middle of the 15th and the middle of the 16th centuries,

whose specific function it was to pray for the souls of the deceased.

It was believed during the Middle Ages that the soul of the deceased

had first to pass through purgatory before being received into heaven.

The soul's entry into heaven could, however, be accelerated by the

prayers of the living. Such prayers for the deceased became a task for

the clergy during the late Middle Ages; people could pay to have a mass

or a memorial service said for their parents, for another man or woman

or even for themselves. The rich, therefore, could have a mass said

once a year, once a month or even once a week. The central part of such

a memorial service was in effect the passage to the grave, with the

preferred psalms for the occasion being Miserere mei Deus

(Psalm 50) and De profundis clamavi (Psalm 129). Such services

were taken not only by the churchwardens and the memorierneesters

but, from the middle of the 15th century onwards, also by the Masters

of the Hours. These last-named are interesting from the point of view

of the history of the Leiden choirbooks, for it was they who ordered

the manuscripts and used them in their services.

The singing of the seven liturgical hours grew enormously in popularity

in the Netherlands during the 15th century. In point of fact, a College

of the Seven Liturgical Hours was simply an imitation of a chapter. In

chapter churches, just as in convents and monasteries, the hours

— also called the Office or choral prayer — were sung:

Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. Matins

and Lauds were combined to form the nocturnal office whilst Vespers and

Compline together formed evening prayer. If we count from Matins to

Compline, we have eight hours in total; why then is there this

discussion of a College of the Seven Liturgical Hours? The explanation

is, however, extremely simple: Matins and Lauds were combined into one

service, the nocturnal office, in non-cloistered churches during the

Middle Ages and therefore seven were left over. Parish churches

naturally sought more honour and glory and so imitated the rituals of

the chapter churches. A separate college was then created for the

singing of the Office, be this a few times per year, a few days per

week or even daily. A special college was founded in various places for

the singing of the seven liturgical hours. The first city to acquire

such a college seems to have been Leiden (ca. 1440) with other cities

following rapidly: Rotterdam (1449), Delft (1450-51 in the Oude Kerk

and 1456 in the Nieuwe Kerk), Haarlem (1452), Gouda (1453), Alkmaar

(1456), Amsterdam and The-Hague (1468) to name but a few.

Archives of several of these colleges have survived and their existence

is well-documented in letters of foundation, benefactions and suchlike

transactions. All that we know about a great many other colleges of the

hours, however, is the simple fact that they existed. We can get a good

idea of how such a college was organised from the foundation letter of

the College of the Hours of the Oude Kerk in Delft. The council of the

city of Delft appointed three or four people each year who were

responsible for the administration of the monies and the goods offered

in payment for the Seven Liturgical Hours and also paid the priests

their salary. They were required to appoint seven or eight priests

— more if they found it necessary — who would perform the

rituals of the college. The sacristan was also required to sing with

the priests, unless he had other functions to perform in the church.

The schoolmaster of the Latin School and his pupils were also involved

with the services; music was an important part of education at the

Latin School during the Middle Ages, with the pupils being taught how

to sing Gregorian chant. The schoolmasters had a great amount of work

to do in cities such as Delft and Leiden; they were required to come

with their pupils on the eve of each holy day to sing Vespers and then

Matins, with a Mass and Vespers again on the day itself — this

took place approximately one hundred times per year. Such a burden was

naturally far too heavy for the pupils and their teachers, with the

result that their workload was drastically reduced in 1484.

The priests of the college were required to sing the seven liturgical

hours 'honourably, perfectly and with good manners' each day in the

choir. A mass was also required to be said or sung every day for those

who had donated money or goods to the college.

Not every town or city could boast such a range of devotions; there

were often fewer priests present and Gregorian chant was frequently the

only music to be heard. A tradition of polyphonic music nonetheless

became established in various cities, as was the case in Delft, Gouda,

Rotterdam, Haarlem and, last but not least, in Leiden. Leiden possessed

two colleges of the liturgical hours during the 15th century; the

oldest of these was in the Pieterskerk and the other was in the much

smaller Onze-LieveVrouwekerk.

The earliest reference to the Pieterskerk college dates from 1440. We

can see from the earliest documents that the singing of the Hours

during those years was not yet a permanent fixture. A change in this

came when Boudewijn van Swieten decided to support the singing of the

Hours; van Swieten was highly-regarded in Leiden and had made a

sizeable career for himself in aristocratic circles, finally becoming

treasurer of the court of Holland. Boudewijn had however, despite his

involvement in secular politics, never lost sight of his soul's

salvation. He founded two chaplaincies in the Pieterskerk in 1421 and

in 1427 and seems to have lived opposite the church. He laid down in

his will in 1443 that the money that he had until then given to support

the two chaplaincies was from that date onwards to be used to support

the singers of the College of the Seven Liturgical Hours - all of this,

however, on condition that the Seven Liturgical Hours would be sung

each day in the choir by seven priests, two choirboys and the sacristan

on normal days and with the addition of the schoolmaster and his pupils

on high days and holidays. A mass had to be sung by seven priests daily

at Boudewijn's altar, this being followed by a procession to his grave.

On normal days the seven priests and two Choirs had to recite a Miserere

and a De profundis followed by a Salve Regina after

Compline. The seven priests and two choirboys had to sing a Requiem

Mass on the Mondays that followed days sacred to the Virgin Mary. He

also specified that the chalice and the missal that he himself had

donated were to be used at every service that was held at his altar

situated on the north side of the choir aisle. A final condition was

the requirement that three and later four people be employed to

organise and administer all of the above.

The College of the Seven Liturgical Hours in the Pieterskerk became

steadily more important thanks to later foundations and donations,

although it can be seen from the few surviving documents that its

growth was not spectacular. The body of singers was formed initially by

seven priests and two choirboys, later becoming eight cantors and four

choirboys during the period 1481-1510. The singers and the choirboys

were led by a singing-master. We know the names of fifteen of these who

were active between 1450-1560, of whom the first, master Jacob Tick,

was in many ways the most interesting. Tick was appointed on 1 November

1453 for a period of ten years; his contract of appointment stated that

polyphonic music was to be sung in the Pieterskerk and that he was also

required to give the children music lessons. Parents were required to

pay for this, but if the parents were poor, then Tick was required to

content himself with what they could afford to give. Tick did not serve

his full ten years, for in the meantime he became a bailiff of the Duke

of Burgundy in 1458 and was then appointed singing-master at the St.

Jacobskerk in Bruges in 1463. The other singing-masters in Leiden were

not such high-flyers; we only know the first names of most of them, and

that a few others were also employed in towns such as Gouda, Haarlem

and Rotterdam.

The turnover of singers was very high; this was a cause for such

concern to certain choirs that they resorted to the use of contracts.

The Delft College of the Seven Liturgical Hours signed a contract with

its fellow college in The Hague in which it was agreed that neither

college would employ a singer within a period of two years after he had

left another choir. The appointment of a singing-master was also not

always a real guarantee of quality of musical performance, for there

were regular complaints about the singers' work. Several such letters

of complaint have been preserved in the Leiden archives, in which we

can read that singers arrived late for their choral duties, that they

did not sing the Gregorian chant with the necessary tranquillity but

rather rushed through the music, that they no longer replied with the

traditional Amen or Deo gratias after the precentor had finished, that

they chattered during the services and that they were already changing

out of their liturgical robes while they were still sitting in choir.

Such complaints were not limited to Leiden: there were complaints in

many parts of Holland that the psalms were being sung too quickly and

that the pauses that should be made between the verses of the psalms

were not being observed.

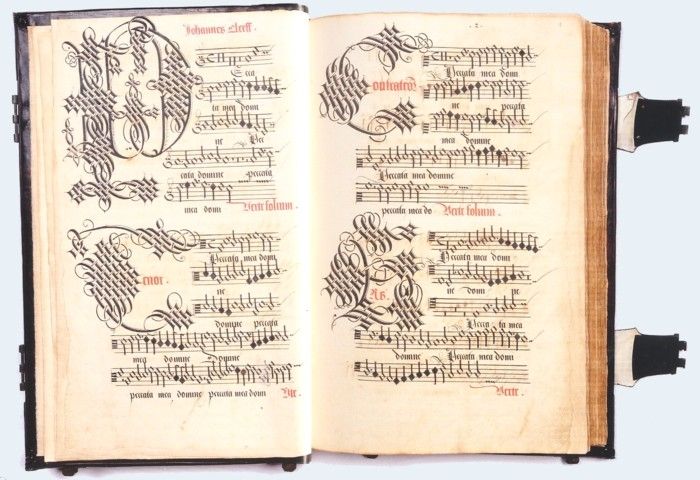

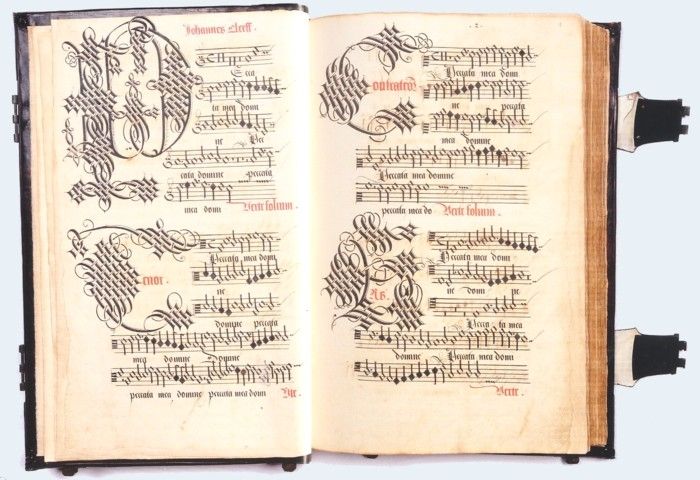

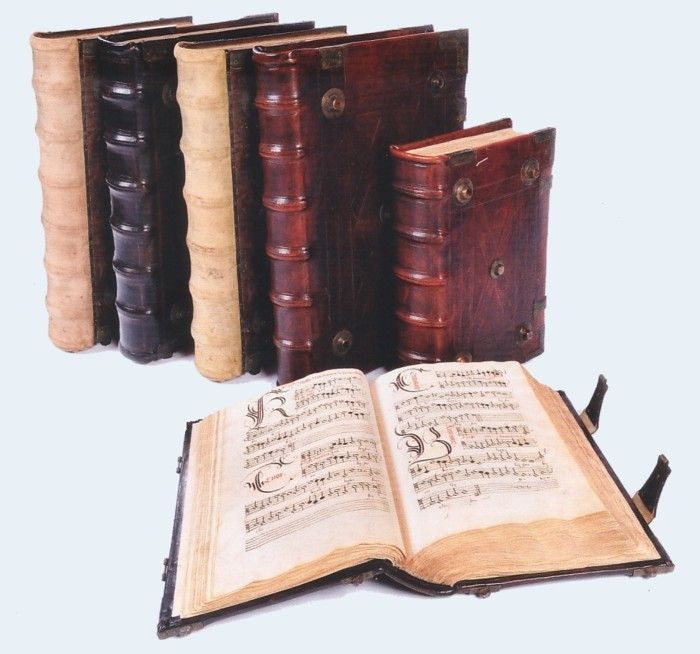

What exactly did these singers of the Hours sing in the Pieterskerk? We

are extremely fortunate that six choirbooks that were ordered for this

purpose in the middle of the 16th century were preserved. They are the

only books of music that have survived from all of the Colleges of the

Seven Liturgical Hours that existed in the Netherlands. We know from

old inventories that comparable manuscripts were used in Haarlem, in

The Hague, in Delft, in Gouda, in Dordrecht and in Rotterdam. The

Leiden choirbooks are therefore the only collection that can now give

us an impression of the repertoire that was sung in these churches. The

six choirbooks — that were marked from A to F during the 19th

century — were clearly made to be used: they were copied onto

paper rather than on expensive parchment, provided with a few decorated

initials letters in black or red ink and contained repertoire that was

intended for general daily use. (illustration 3) Choirbooks A to D are

large in size (ca. 55 x 39 cm) in comparison with books E and F, which

were written on much smaller sheets of paper (ca. 41 x 28 cm). We know

with certainty that manuscripts A to C were copied out by the Leiden

music copyist Anthonius de Blauwe, who had also copied out choir-books

for other localities in Holland. The first mention of his name is to be

found in the account books of the Masters of the Hours in Gouda; we can

see in the sections dating from 1547 that monies were paid out to

'Master Anthonis, living in Leiden'. His name recurs in the accounts of

the Masters of the Hours in Delft from 1547 through 1549. Other

choirbooks prepared by him have been found in Amsterdam, in Dordrecht

and in Rotterdam. The first Leiden choirbook dates from 1549, whilst

the second and third date from 1559. Manuscripts D to F are undated,

but clearly were prepared between 1549 and 1565; they too appear to

contain many pages in Anthonius de Blauwe's hand.

De Blauwe lived on the Vollersgracht in Leiden from 1546 onwards and

was known as a writer and schoolteacher. He was not a teacher at the

Latin School, but ran a school that taught children how to write. He

presumably had no more choirbooks to copy out by 1565, for he was then

appointed to teach orphans how to write, at times in the orphanage and

at times in his own home. The most interesting document concerning de

Blauwe that has survived is a handwritten letter to the singing master

of the College of the Hours in Gouda: here de Blauwe explains that he

had made a splendid choirbook with motets for the singing-master in

Amsterdam and that it had turned out so well that he had decided to

make another copy of it. He then offers this copy to the Gouda college.

Our impression of de Blauwe is of a clever businessman; his true

profession was either writer or schoolmaster, although he earned extra

money by supplying choirbooks.

If we look at the repertoire that de Blauwe was commissioned to copy

out by the Dutch Colleges of the Hours, we see the names of all the

renowned Franco-Flemish composers before us. The first of these was

naturally Josquin des Prés; he had died in 1521 but his music

was of such quality that it circulated throughout Europe until late in

the 16th century. Composers who were contemporaries of the singers are

also represented, with Jacobus Clemens non Papa, Thomas Crecquillon

(singing-master to Charles V), Nicolas Gombert (master of the choirboys

in Charles V's service), Johannes Lupi, Pierre de Manchicourt, Jean

Mouton, Jean Richafort and many others. Works by local composers are

also regularly represented, with singing-masters from Leiden including

Claudin Patoulet (who, as can be seen from a contract from his time in

Haarlem, once turned up drunk when he had to sing), Joachimus de Monte,

Michael Smeekirs and Johannes Flamingus, who added some of his own

works to the choirbooks.

What type of music did these composers write? Primarily polyphonic

masses of course, thirty-three of them in total. In one of the books

— manuscript F —more than twenty different settings of

sections of the mass are notated; these are of course the sections that

make up the Ordinary of the mass — the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo,

Sanctus and Agnus Dei — as they would be the most frequently

used. The Magnificat, the impressive final canticle of Vespers, was

also popular with twenty-five settings, as was the Nunc dimittis with

thirteen different settings. The combined manuscripts contain no less

than sixteen different versions of the Salve regina, this being sung

during the countless services in honour of the Virgin. Alongside all of

these are also around two hundred motets that vary from short hymn

settings that could be performed during the Office to large-scale

Marian motets that were highly suitable for the weekly singing of the

Lof (Salve). A selection of different polyphonic compositions was

therefore available for all the various services that had to be

observed.

An end, however, had to come to the illustrious history of the Dutch

Colleges of the Liturgical Hours, as indeed it did, and with

considerable uproar. What then happened to the Leiden choirbooks? After

the Reformation they ended up in the hands of the Leiden city council.

The council received a request in 1578 that the choirbooks might be

used once again, for there were several enthusiastic singers who wanted

to make music with the aid of the choirbooks and approval was given for

this. This continued for approximately twenty years and then the

choirbooks were returned to the city council once again. They were shut

away in large chests and stored in the trustees' chamber in the city

hall. The next mention of them dates from 1876, when the choir-books

were transferred from the city offices to the Stedelijk Museum De

Lakenhal, where they were placed on permanent exhibition. The museum

had, however, grown so much by 1931 that it could no longer provide

storage for these splendid books. Five manuscripts were transferred

back to the city archives, where they still remain; one of the

manuscripts — Book C from 1559 — is still on display in the

Lakenhal.

Eric Jas

translation: Peter Lockwood