medieval.org

Leonarda LE 340

Recorded at Alice Barler Recital Hall, Wells College, Aurora, New York, September, 1994

released in 1997

medieval.org

Leonarda LE 340

Recorded at Alice Barler Recital Hall, Wells College, Aurora, New York,

September, 1994

released in 1997

Medieval Chant,

Songs, Dances

Beatriz, Countess de Dia · 12th c., France

01 - A Chantar [7:32]

soprano, medieval fiddle, lute

Maroie de Dregnau de Lille · 13th c., France

02 - Mout m'abelist quant je voir revenir [1:37]

soprano, psaltery, medieval fiddle

Queen Blanche · 1188-1252, France, b. Castile

03 - Amours, u trop tart me suis pris [4:26]

soprano, psaltery, medieval fiddle

anonymous · c.1400

04 - Trotto [1:23]

recorder, nakers

anonymous · 13th c.

05 - Estampie [1:25]

recorder, symphonia

Hildegard von Bingen · 1098-1170, Germany

06 - In Evangelium [1:51]

soprano, organetto

07 - O viridissima virga [4:32]

soprano, medieval fiddle, psaltery

08 - O Ierusalem, aurea civitas [7:17]

soprano, medieval fiddle, symphonia

anonymous · c.1400

09 - Saltarello [1:29]

recorder, lute

10 - Saltarello [1:54]

recorder, tambourine aux cordes

11 - La Manfredina [2:38]

medieval fiddle, lute

16th & 17th

Century Songs & Lute Duets

Anne Boleyn · 1507-1536, England

12 - O Deathe, rock me asleepe [7:08]

soprano, lute, bass viola da gamba

Lady Killigrew · 17th c., England / words, John Donne

13 - Sweetest love I do not goe [3:40]

soprano, lute, bass viola da gamba

Giles Farnaby · c.1563-1640, England

14 - Tower Hill [3:24]

two lutes

anonymous

15 - Green Sleeves [2:51]

two lutes

Mary Harvey, Lady Dering · 1629-1704, England

16 - When first I saw Fair Dorris' eyes [2:11]

17 - And is this all? What one poore kisse? [0:55]

18 - In vain fair Chloris, you design (words by Sir Edward

Dering) [2:58]

soprano, lute, bass viola da gamba

anonymous

19 - La Rosignoll (The Nightingale) [2:41]

two lutes

Richard Farnaby · b.1594, England

20 - Nobody's Gigge [2:27]

two lutes

Andrea Folan, Susan Sandman, Derwood Crock

Manuscripts of medieval songs contain only melody, with no

indication of instrumentation. The instruments chosen for this

recording were common in the 12th and 13th centuries. In keeping with

early practices in performance, the instrumentalists have added their

own countermelodies, ornamentation, and, where manuscripts are

ambiguous, rhythmic interpretation. The later songs are performed in

the English lute song style with voice, lute and bass viola da gamba.

Lute realizations for Lady Killigrew and the first two Harvey songs

were supplied by Dr. Sandman.

History has been unkind to the female composer. Until more

recent times, she seemed not to exist at all, as her compositions

sometimes appear under masculine pseudonyms or are claimed by husbands,

brothers, fathers, or other male contemporaries. The women represented

here, spanning the 12th through the 17th centuries in Europe, are

unique and lucky; their work has survived and is recognized.

Countess of Dia allows us a unique personal perspective of a

world ruled by a rigid code of courtly love. The text for this song is

outside the male, more formal, aesthetic of courtly love because of its

directness, immediacy and personal viewpoint. The Countess, wife of

Guilhèm de Poitiers, lived in southern France in the 12th

century, a period favorable for the economic independence of

aristocratic women. The legal system in southern France allowed women

to inherit property; they often ruled their family estates while their

husbands were away fighting in the crusades, freedoms that were

gradually whittled away in later centuries.

Although this was an era when poetry and music by women flourished,

there are only 23 surviving poems by women and only four melodies. We

are fortunate to have both the melody and poetic text for the Countess

of Dia's song, one of only two extant melodies of its kind surviving

from the 12th century.

Maroie de Dregnau de Lille (13th C. France) is an otherwise

unknown poet whose lovely little song presents us with a glimpse into

the secular life of medieval women — the expectation that despite

the chill of winter, a maid should remain joyful and thus increase her

worth.

Queen Blanche (1188-1252) was born in Castile, then a kingdom in

what is now central and northern Spain. Upon marriage, she became Queen

of France, and governed France as regent during the minorship of her

son Louis IX, and then again in his absence during the 7th crusade. Of

noble birth, Blanche was in the position to benefit from an education

otherwise unavailable to women, or to most men. Her nobility and its

accompanying education and wealth probably helped ensure the survival

of her song through the centuries.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1170), a unique and extraordinary

woman by any century's measure, wrote books on natural science,

theology and medicine, as well as the first morality play set to music.

She composed a large collection of religious music, Symphonia

armonie celestium revelationum (Symphony of the harmony of

celestial revelation). Of noble birth, her resources probably helped

her to found her own monastery in Germany, and she earned the respect

of kings, emperors and churchmen. The title of her collection,

"Symphonia," refers, in addition to its more general musical meaning,

to the medieval style hurdy-gurdy called a symphonia used in this

performance of O lerusalem. The songs in this collection are in

Latin, and, as common with plainsong, were written as a single line of

music. This performance includes echoes, counter-melodies and drones

inspired by Hildegard's melodies and poetry.

Several centuries of social, political, and artistic change are

reflected in the English compositions on this CD. Multi-part

compositions replace single-line melodies, the number of surviving

manuscripts increases, and a rising middle class encourages

music-making in the home.

O Deathe, rock me asleepe is attributed to Anne Boleyn

(1507-1536), the second wife of King Henry VIII and mother of Elizabeth

I. Anne's father attained a high position under the young Henry VIII

and spent several years as Ambassador to France. Anne lived at the

French court from age 12-16. We know she was trained in music and

dancing, owned a virginals (a keyboard instrument similar in sound to a

harpsichord), and played the lute. She had an excellent reputation as a

composer and performer. This song is said to have been written by her

when she was in the Tower of London facing execution for treason,

though her only crime was probably her failure to produce a male heir.

Lady Killigrew's lovely setting of this poem by John Donne

appears in an English manuscript from the early years of the 17th

century. Though her first name is not indicated and thus her exact

identity difficult to ascertain, she may be related to Anne Killigrew,

a poet and painter who lived just before the Restoration. The unclear

identity of Lady Killegrew is a good example of the dilemmas music

historians face when researching this material.

Giles Farnaby (c. 1563-1640) was a "joyner and musician" (a

woodworker, composer and music teacher) who earned a Bachelor of Music

from Oxford in 1592. More than fifty of his pieces are included in the Fitzwilliam

Virginal Book, a major collection of English keyboard music. We

included Farnaby's piece Tower Hill because it refers to the infamous

prison where Anne Boleyn was held prisoner earlier. We perform it on

two lutes instead of keyboard.

Richard Farnaby (b c. 1594-?), whose piece closes this

recording, was Giles' Farnaby's son. Less is known about Richard, but

four of his pieces are in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

Anonymous Lute Duets are taken from the Jane Pickering Lute

Book (1615-1645), which contains music copied in three different

hands. It was customary at the time, when printed music was not so

readily available, to write down familiar tunes, one's own tunes, and

tunes composed by others. The anonymous lute duets on this recording

were copied in the same hand that wrote "Jane Pickeringe owe [sic]

this Booke 1616," presumably by Jane Pickering herself. Both the main

part of the Jane Pickering Lute Book and the Fitzwilliam

Virginal Book were written in the 17th century during the "Golden

Age" of Elizabethan and Jacobean lute music.

Mary Harvey, the Lady Dering (1629-1704) studied music at Mrs.

Salmon's School, a fashionable English girls' school where she also

learned Latin, French, "all manner of cookery," fancy needle work, and

dancing. After her marriage at age nineteen, she began lute lessons

with Henry Lawes, a composer at the court of Charles I. Three of Lady

Dering's songs were included in Lawes' publications of Jacobean lute

songs, and although the title page mentions only Lawes as composer,

Lady Dering's name appears on the music itself. The text for the last

song is by Sir Edward Dering.

—Susan G. Sandman

Elizabethan Corversation was founded in 1982 as a lute duet

specializing in the music of Shakespeare's time. The ensemble now

performs various repertoires.

Susan G. Sandman is an early music performer and musicologist

who received her B.A. in music from Vassar College and a Ph.D in

musicology from Stanford University. A Professor of Music at Wells

College in New York's Finger Lakes region, she teaches music history

courses and directs the Wells Consort, a student group that performs on

period instruments. Dr. Sandman is published in journals in the areas

of early music and women composers, and researches the music for

ELIZABETHAN CONVERSATION.

Derwood Crocker began private music study in early childhood.

His skills in design and traditional woodworking led to the making of

musical instruments, and he has been a full-time craftsman/musician

since 1965. The Crocker workshop has produced hundreds of instruments

for performers and ensembles nationwide, many of them one of a kind.

His instruments are in the collections of numerous colleges and at the

Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. He performs in ELIZABETHAN CONVERSATION

and lectures on the history and making of early instruments at

workshops and seminars.

Soprano Andrea Folan earned degrees in voice and German from

the Oberlin Conservatory and College and did graduate work in

performance practice at the Mannes College of Music in New York. Her

special interest in the German Lied repertoire with fortepiano has led

to extensive performances in the U.S. and abroad with acclaimed

fortepianists, including Malcolm Bilson, in recital series and at

festivals, including Festival Flanders (Brugge, Belgium) and the Boston

Early Music Festival. Andrea recently released a solo CD of Haydn songs

with fortepiano to critical acclaim. Her early music credentials

include performances with the Folger Consort and Apollo's Fire, among

others. She is a founding member of The Public Music and is also an

active oratorio specialist. She maintains a private voice studio in

addition to her duties as a vocal coach at Cornell University.

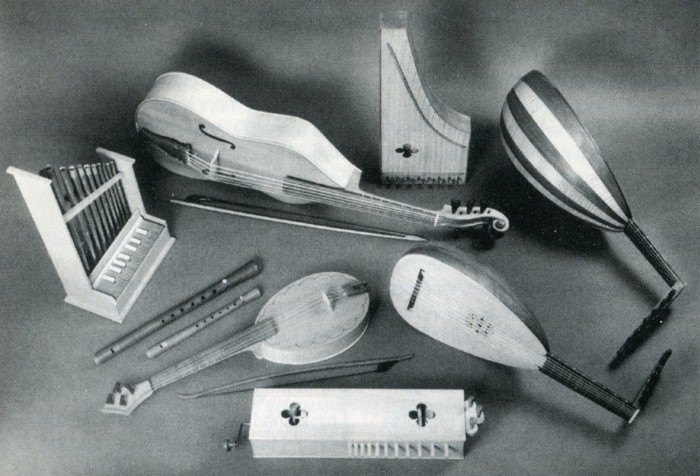

Pictured, bottom, then clockwise:

symphonia, medieval fiddle, recorders, organetto, bass viola da gamba,

psaltery, lutes.

Not pictured: nakers (a hand drum from the Middle East), traditional.

Performances:

Susan Sandman: medieval fiddle, recorders, lute, bass viola da gamba.

Derwood Crocker: lute, psaltery, synnphonia, organetto, nakers.

Instrument makers:

Symphonia, medieval fiddle, organetto, and top lute made by Derwood

Crocker.

Other lute by Middleton.

Recorders by Bob Marvin.

Bass viola da gamba by an anonymous Swiss maker, 1970.

Music Sources

Dia: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS Fr. 844, Fol. 204R.

de Lille: Le Manuscrit du Roi.

Queen Blanche: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, MS f.fr.

21677.

Hildegard: Dendermonde Codex. This recorded performance omits

verses 4 and 6 in "O lerusalem."

Boleyn can be found in Briscoe, ed. Historical Anthology of

Music by Women (1987).

Killigrew: Oxford Tenbury MS 1018; ornamented version from

Bodelian Library. Add. 10337 fol. 55v.

Harvey: Henry Lawes' Second Book of Select Ayres and

Dialogues (John Playford, 1655).

Anonymous lute duets: The Jane Pickering Lute Book

(1615-1645) and Folger MS 1610.

Farnabys: Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. Lute realizations

for "Sweetest love I do not goe, When first I saw Fair Dorris' eyes,"

and "And is this all? What one poor Kisse?" were supplied by Dr.

Sandman.

"In vain, fair Chloris" is published in "English Songs," Musica

Britannica, Vol. 33, ed. Ian Spink (London. Stainer & Bell,

Ltd. 1971).

Text Sources

Dia original text from Meg Bogin, The Women Troubadours

(NY: Paddington Press/Two Continents Publishing Group, 1976).

Translation: Women in Music: An Anthology of Source Readings from

the Middle Ages to the Present, ed. Carol Neuls-Bates (NY: Harper

& Row, 1982).

de Lille: "Mout m'abelist": Maria V. Coldwell, Jougleresses

and Trobairitz: Secular Musicians in Medieval France, in Women

Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150-1950, ed. Jane Bowers

and Judith Tick. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), p. 52.

Visual

Representations of Women in the Middle Ages

Cover art: "Angel with Symphonia," c. 1360, possibly Pisan. Samuel H.

Kress Collection, ©1966 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of

Art, Washington D.C.

A good source for pictures of 15th C. women musicians and artists is The

Medieval Woman, An Illuminated Book of Days, ed. Sally Fox.

(Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1985).