Zingen en spelen in Vlaamse steden en begijnhoven, 1400-1500

Music in Flemish Cities and Beguinages / Capilla Flamenca

medieval.org

capilla.be

Eufoda 1266

1997

1. Tam verenanda [1:34]

anoniem / Brussel, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I ms. IV 421

2. Credo [6:40]

anoniem / Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek ms. 15

3. Verbum tuum ~ In cruce

[2:32]

Johannes RONDELLI, actief 1436

4. La Spagna [2:05]

Alfonso de la TORRE, actief ca. 1450

5. Jesus ad templum [2:11]

anoniem / Brussel, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I ms. IV 421

6. D'ung aultre amer

[2:47]

Alexander AGRICOLA, ca. 1446-1506

7. Beatus Landoaldus [7:50]

anoniem / Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek ms. 15

8. Ihesus coninc overal

[4:48]

anoniem / Brussel, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I ms. IV 421

9. Joly et gay [1:48]

Hugo de LANTINS, actief 1420-1430

10. Tout a coup [2:22]

ADAM, actief 1420-1430

11. Omnes Mauritium [2:31]

anoniem / Brussel, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I ms. 9786

12. Chanson [3:44]

anoniem / Firenze, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, ms. Banco Rari 229 /

Tongeren, Sint-Nildaaskerk, Varia s.s.

13. In tua memoria

[2:26]

Arnoldus de LANTINS, actief 1430

14. Salve, sancta parens

[3:07]

Johannes BRASSART, ca. 1400-1451

15. Verbum patris hodie

[2:48]

Johannes de SARTO, actief 1390-1440

16. Ave virtus ~ Prophetarum

[5:17]

Nicolaus GRENON, ca. 1380-1456

17. Prevalet simplicitas

[2:15]

Arnoldus de RUTTIS, actief 1420

18. Ave Virgo ~ Sancta Maria

[3:15]

Johannes FRANCHOIS, actief 1378-1415

Capilla Flamenca

Dirk Snellings

Katelijne van Laethem · sopraan

Katrien Druyts · sopraan

Marnix de Cat · contratenor

Jan Caals · tenor

Lieven Termont · bariton

Dirk Snellings · bas

Credo:

Patrick Van Goethem, contratenor

Jan van Elsacker, tenor

Bart Demuyt, bariton

Paul Mertens, bas

Sophie Watillon, discant gamba

Eugeen Schreurs, alt gamba

Liam Fenelly, bas gamba

William Dongeois, Michèle Vandenbroucque, Franck Poitrineau · Alta Capella

Wim Diepenhorst, orgel

Samenstelling en musicologisch advies: Eugeen Schreurs

Transcripties

Barbara Hagg, Royal Holloway, Londen: #7

Eugeen Schreurs, Alamire Foundation, K.U. Leuwven: #1, 4, 5, 11, 13

Instrumentenbouwers:

Gamba's: Toon Moonen

Orgel: Christian Ancion (ca. 1644), Sint-Truiden, Begijnhofkerk

Opname: Kapel van het Iers College, Leuven, mei 1995

Digitale opname en montage: Jo Cops

Artistieke leiding: Paul Beelaerts

Grafische vormgeving: Daniël Peetermans

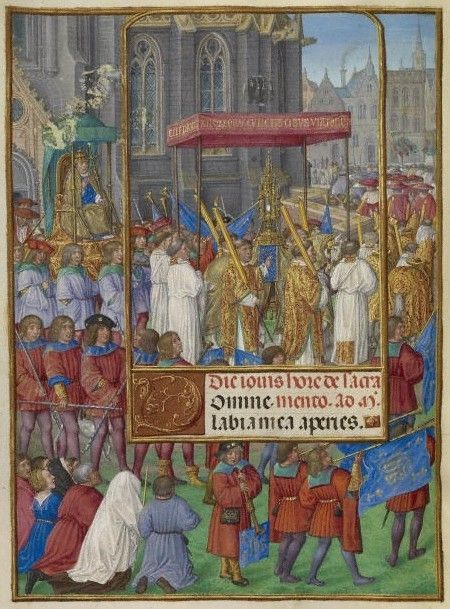

Coverillustratie: Gerard Horenbout · Processie op Sacramentsdag,

Getijdenboek (Spinola-getijdenboek'),

Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.ML.114 (Ms. Ludwig IX.18), fol. 48v

© 1997 Davidsfonds/Eufoda

Music for Burghers, Beguines and Clerics in the 15th Century

EUGEEN SCHREURS

Flanders, with prosperous cities such as Bruges and Ghent; Brabant with

its ‘courtly cities’ of Brussels and Mechelen respectively;

the rising metropolitan city of Antwerp and the independent

prince-bishopric of Liège, with besides its capital also smaller

towns such as Tongeren and Sint-Truiden: these were all regions and

towns where music, monophonic as well as polyphonic, was nurtured.

Courts - such as the Burgundian-Habsburg court - collegiate churches,

parish churches, monasteries, beguinages and brotherhoods were the main

institutions which guaranteed a flourishing and rich musical life which

reached such a highly professional level that it was renowned well

beyond these regions’ borders. It even inspired imitation, as can

be seen in the fact that Maximilian had his court chapel organised

after the ‘Brabant model’.

The diversity in sound in these - mainly religious - institutions, and

the co-operation with wandering minstrels, burghers and municipal

authorities, resulted in a musical boom, showing diversity as well as

quantity and quality. The interchange between these groups of musicians

resulted in a sound which is no longer known and which today, even in

authentic performance practice, is seldom heard in all its diversity.

In this context the London and Oxford professor Reinhard Strohm made an

inspired choice when coining the term

‘townscape-soundscape’ in his pioneering book Music in

Late Medieval Bruges.

For a long time musicology, with performers in its wake, has made an

exaggerated contradistinction between Gregorian chant and polyphony.

Presumably this distinction had at first a didactic reason, but after a

while it started to lead its own life. Admittedly, at the time the term

‘simple sanck’ was also used - ‘simple song’

for denoting plainchant. On the other hand, musical sources also speak

of ‘musieck in discante’ - ‘descant music’

which meant ‘learned’ polyphony. However, this never

implied any idea of opposites. On the contrary: both genres were

commonly used in perfect symbiosis during the numerous church services.

Examples of more ‘recently’ composed plainchant are the two

responsories from the Office of Saint Landoaldus (‘Beatus

Landoaldus’), a saint whose relics were transferred during the

10th century from the village of Wintershoven, which was owned by St.

Bavon’s Abbey, to Ghent, where he was worshipped from then on.

The work was written in a 15th century gradual (Ghent, University

Library, MS 15) originating from St. Bavon’s in Ghent. Monodic

spiritual songs could also be included in ‘simple song’,

such as Ihesus coninc overal, which can be found in the library

of the Ter Nood Gods monastery in Tongeren (Brussels, Royal Library

Albert I, MS IV 421).

The order of precedence was also diffèrent from what we have

long thought in the 20th century: for late medieval man the ancient,

austere Gregorian chant - including its local, specific offices - came

top and the complex polyphony provided the necessary

‘varietas’ or variety in the canons’ choir.

Polyphonic music was also often based on the monophonic spiritual

repertoire. An example is the complex isorhythmic motet Ave

virtus/Prophetarum by Nicolas Grenon, who worked in Cambrai, the

Burgundian court and the Papal Chapel in Rome and who was also canon at

Dendermonde. The tenor part, which supports the whole composition with

its slow notes, is based on the finale of the sequence Laetabundus.

The fact that in such isorhythmic motets several texts were sung

simultaneously, was apparently no problem. Of course - and it makes

this probably easier to understand - this type of polyphony was often

meant for connoisseurs, ‘learned’ canons who probably knew

the complicated texts beforehand or who sometimes wrote them themselves.

In line with the somewhat exaggerated distinction between Gregorian

chant and polyphony, the role of ‘simple polyphony’ has

until fairly recently also been underestimated and the research in this

field neglected. The performance of this type of music has received

equally little attention, because it was thought too

‘primitive’. Nevertheless, these are the roots of

polyphony. Polyphony was of course closely linked to plainchant and it

was also common practice to improvise polyphonically above the

plainchant. These ex tempore harmonisations of a plainchant melody from

the Gregorian book (‘cantare super librum’) were held in

high regard - in 16th century Italy, for example, it was also known as

a form of ‘contrapunto alla mente’. There are still quite a

few myths in circulation regarding this simple, homophonic music

practice in faux-bourdon style, which remained common until the 18th

century. The remaining examples are few and far between and have not

yet been catalogued completely, but those pieces that we do know are

particularly instructive because they offer a better understanding of

the way polyphony came to be.

The influence of the Modern Devotion movement helped to spread the use

of this simple polyphonic style in monastic congregations belonging to

the order of Windesheim. The previously mentioned Tongeren manuscript

(Brussels, Royal Library Albert I, MS IV 421), from the second half of

the 15th century, is remarkable in this respect. It contains monophonic

and two-part Dutch and Latin songs and was discovered as recently as

1945 in Jongenbosch Castle. In the polyphonic settings of this

manuscript the old technique of 13th century descant with parallel

fifths and octaves and counter-movements (for example, Jesus ad

templum) was consciously reverted to, while piercing dissonances

were not avoided (for example, unprepared seconds in Tam veneranda).

From later periods it transpires that this style was also in use in

beguinages. An example of this can be heard in a late 16th century Ave

verum which originates from the Great Beguinage in Mechelen and is

now owned by the Leuven Theological Library (MS 3049h).

This elementary form of simple polyphony was also common, up to a

point, in collegiate churches where it was given a place besides

plainchant and complex polyphony. In the aristocratic convent of

Munsterbilzen, which was in fact a collegiate church with a double

chapter of 24 aristocratic female and four male canons, a similar

compositional procedure was known - for example, the two-part Omnes Mauritium in praise

of the local Bilzen patron saint Maurice. The work of Johannes Brassart

shows very clearly that this improvisational technique had a direct

influence on complex, composed polyphony. Brassart usually worked for

the German emperors and sang, with Dufay, for a time at the Papal

Chapel in Rome. His compositions include the three-part introit Salve,

sancta parens where in some passages a somewhat more elaborated

form of improvised counterpoint can be clearly heard. A four-part

‘Credo’ originates from St. Bavon’s Abbey in Ghent,

which was later given collegiate status. The tenor was originally

written monophonically, but the addition of a bass and two upper parts

resulted in a composition in faux-bourdon style, although a number of

alterations in the bass give a rather modern effect. It is a

magnificent work, impressive in all its simplicity. In this composition

the organ is also used alternately with polyphonic singing, as can be

deduced from the indications ‘chorus’ and

‘organum’.

Another over-emphasised contradistinction is that between spiritual and

profane music. Both genres were partly performed by the same musicians,

which can be deduced from the contents of certain manuscripts (for

example, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS 213 or Bologna, Civico Museo

Bibliografico Musicale, MS Q15). This is no different in the more

recently discovered fragments of a Tongeren ‘Songbook’

which was probably meant for use in the collegiate church. Here,

besides a Salve Regina-like setting, a very distinct reading

can be found of Ockeghem’s D’ung aultre amer, a

chanson which was later repeatedly reworked, by Alexander Agricola

among many others. Besides being performed by church musicians, this

type of mixed spiritual-profane repertoire was also sung and played in

domestic situations or by travelling musicians, often on instruments.

When played instrumentally, the texts of the vocal models was usually

left out, as in the ‘dream-like’ wordless chanson which

probably originates from a rondeau.

There was a real distinction, however, between domestic music making

and music in open air, especially in the choice of instruments:

‘bas’ (low, soft) in contrast with ‘haultz’

(loud). Each sizeable town had an ensemble of at least three wind

instrument players at its disposal, an ‘alta capella’,

consisting of cornetto, shawm and sackbut. During processions or

important liturgical feasts (for example Corpus Christi) the services

of these musicians were required and others taking part were priests,

guild members, monks, town magistrates and the faithful: varied

processions indeed, as is evident from many detailed archival

descriptions. Often the musicians marched in front of the priest who

carried the sacrament under a canopy. Besides dance music and

improvisations on profane and spiritual tenor melodies, these town

musicians gradually started playing spiritual motets as well, as for

example Verbum Patris hodie by Johannes de Sarto.

Translation: Paul Rans, Nell Race