Johannes BRASSART (ca. 1400/05—1455)

In festo Corporis Christi / Capilla Flamenca

medieval.org

capilla.be

Ricercar 233362 | RIC 204 | I Fiamminghi V

2000

1. Redeuntes in idem [1:51]

anonyme, Buxheimer Orgelbuch

Johannes BRASSART

2. Introitus. Cibavit eos [4:07]

3. Kyrie [3:18]

4. Gloria [4:25]

5. Alleluia. Caro mea [3:03]

6. Evangelium. Caro mea [1:45]

chant grégorien

Johannes BRASSART

7. Credo [9:57]

8. Offertorium. Sacerdotes incensum [1:38]

chant grégorien

Johannes BRASSART

9. Sanctus [4:35]

10. Agnus Dei [3:14]

11. Communio. Quoties cumque [1:40]

chant grégorien

12. Longus tenor [3:34]

anonyme, Buxheimer Orgelbuch

Gilles BINCHOIS

13. Te Deum [10:38]

14. Redeuntes In Idem mi de eadem mensura [1:31]

anonyme, Buxheimer Orgelbuch

CAPILLA FLAMENCA

Dirk Snellings

Marnix DE CAT, Stratton BULL, altus

Jan CAALS, Stephan VAN DYCK, tenor

Lieven TERMONT, Bart DEMUYT, tenor

Dirk SNELLINGS, Paul MERTENS, bassus

PSALLENTES

Hendrik Vanden Abeele

Joachim COME, Steve DE VEIRMAN, Carl MESSIAEN

Russell MILBURN, Joost TERMONT, Hendrik VANDEN ABEELE

direction : Hendrik VANDEN ABEELE

Joris VERDIN

Orgel der Reformierte Kirche in Rysum (1457-1513)

Deze opname werd gerealiseerd met de steun van het

Ministerie van

de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, afdeling Muziek, Letteren en Podiumkunsten.

Cet enregistrement a été réalisé avec

l'aide du

Ministère de la Communauté Flamande,

département de la Musique, des Lettres et des Arts de la

scène.

Enregistrement : Eglise de Bolland, Septembre 1999

Prise de son et direction artistique : Jérôme LEJEUNE

Production : Jérôme LEJEUNE

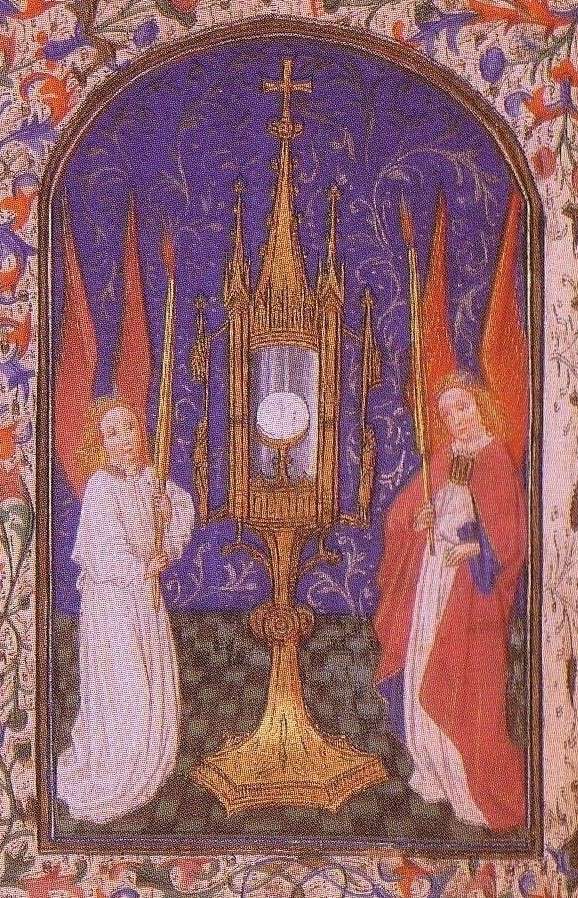

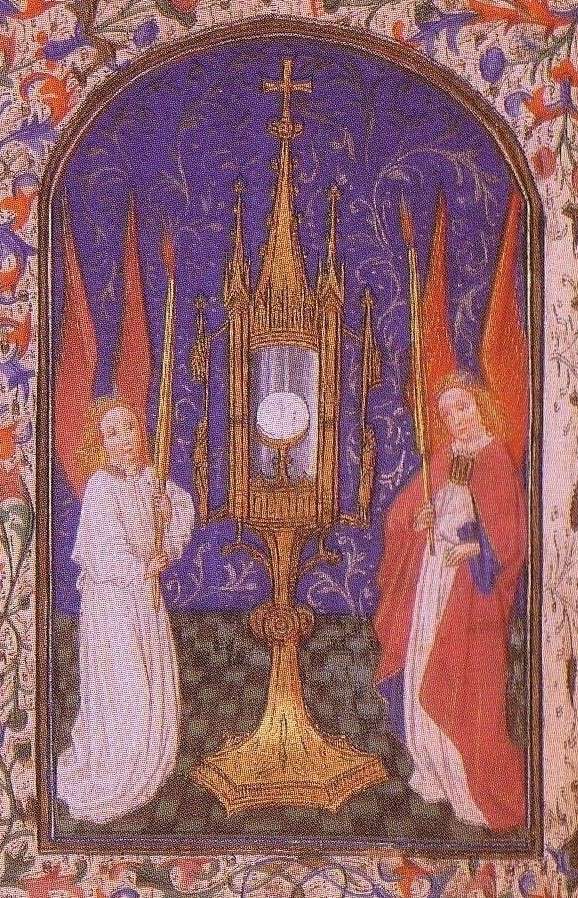

Ilustration du recto : Miniature extraite du Ms. GEN 288 (fol.38v),

Glasgow, University Library

Merci à Katrien Smeyers

(Studiecentrum voor Vlaamse Miniaturisten, K.U. Leuven)

pour son aide dans le choix de cette illustration.

Edicion M10 Distribution

© & Ⓟ 2000 RICERCAR

Corpus Christi in Tongres, 1444

with works by Johannes Brassart and his contemporaries.

The

Episcopal-Principality of Liège included not only the seat of the

Prince Bishops but also such medium-sized towns as Tongeren, St-Truiden,

Maastricht and Huy. It played a considerable role in first creating and

then spreading the polyphonic style around Europe. It was in effect

here in the second half of the 14th century that such executant

composers as Ludovicus Sanctus of Beringen, the magister in musica

to the Pope in Avignon, and Johannes Ciconia in particular laid the

foundations for the expansion of a section of its cultural patrimony far

beyond the borders of the archdiocese. These composers were active

primarily in Italy and, to a lesser degree, in the German empire.

The

work of the composers from this region attained its apogee in the first

quarter of the 15th century, from a qualitative as well as from a

quantitative standpoint. Composers of the time included H. Battre (based

in Ciney), Johannes Brassart (of Lauw), Petrus Fabri of Rommershoven,

Johannes Franchois de Gemblaco (Gembloux), the brothers Hugo and

Arnoldus de Lantins, Johannes de Lymburgia, N. Natalis (singing master

at St. Lambert's in Liège), Johannes Rondelli (singing master in

Tongres), Nicolaus de Ruttis (Rutten) and Johannes de Sarto. A marked

decline began in 1467 when the Burgundian troops attacked the

archbishopric of Liège and sacked the city; the unfortunate consequences

of this would be felt for a long time to come.

The prosperity of

Liège musical life was certainly due to the eight collegiate churches

(the cathedral included) that enriched the 'City of Fire'. Tongres also

had an influential chapter of twenty canons that was partially under the

wing of St. Lambert's in Liège, its mother church. A dean stood at the

head of the chapter. Between the years 1381 and 1403 this was no-one

less than Radulphus de Rivo, an erudite canon who had studied at the

universities of Bologna and Paris and who in 1397 had been rector of the

university of Cologne for a short period. He was also the author of

several books on liturgical matters and greatly reformed the liturgy of

the church of Notre-Dame in Tongeren. It was at his instigation that a

collection of liturgical books was assembled at the end of the 14th

century; it included several richly illustrated graduals, antiphoners

for the two sides of the canonical choir, processionals, a manual

specifically for the canons' cantor and other such works. The nucleus of

this collection has survived, and it is of this that the present

recording has been able to make such grateful use. The Dean of the

chapter in the time of Johannes Brassart was Gisbertus de Eel

(1441-1455); several important constructions were undertaken during his

deanship, including a new tower in 1442 that is still standing and the

north transept in 1456.

The second in the hierarchy after the

dean was the canon-cantor, a function that had evolved during the 15th

century into a sort of ‘master of ceremonies’ whose tasks were no longer

restricted to purely practical and musical affairs. This post was taken

up by master Johannes Brassart. As luck would have it, Brassart's works

were known well beyond his country's frontiers and many of those that

were written for the feast of Corpus Christi have been preserved. The

majority of the settings of the ordinary of the mass that are performed

here are from his hand.

The dean or the cantor took precedence

during the services on important feasts. They were assisted by the

canonical choir, of whom there were often no more than fifteen because

of absences. Amongst them there were also several non-resident

musicians, including Johannes Brassart (1438, 1442-44) and Henricus

Tulpin (1381), also one of the Papal singers. The canons who were

present were supposed to assist at all the ceremonies and to pray and to

sing during the daily office and at the capitular mass. This was also

so for the more than thirty chaplains, who would celebrate between one

and three masses per week.

In the larger churches and the

cathedrals one could also call upon the services of the “lesser canons”

who were also termed “greater vicars” and who were primarily responsible

for the solo passages of Gregorian chant. We cannot rule out the

possibility that a small group of the better singers, probably the

younger ones, would have taken the solo lines in the Gregorian chant in

the smaller collegiate churches.

Another group that undoubtedly

took over the more difficult sections of the chant was formed by the

vicars, literally those who replaced the absent canons. A Papal Bull

that was issued in 1444 and ratified in 1448 reserved six chaplaincies

for these vicars. They were principally responsible for the polyphony

and therefore had to be professional musicians. The highest-ranking of

these was the singing master; he led the ensemble, taught the young

choirboys and eventually also composed the music. Between 1440 and 1449

this was Petrus de Roest, the successor to Johannes Rondelli. Roest was

removed from his position in 1449 for wrongdoing, but from the end of

the same year he became attached to the collegiate church of Notre-Dame

in Antwerp as vicar-singer. The second position in the hierarchy was

filled by the organist, who also sang with the others when he did not

have to play. The organ played either as a solo instrument or in

alternation with the singers, or as accompaniment. The organist in

Brassart's time was Ludovicus van den Borch (1442-1445), who played an

instrument that had undergone radical rebuilding by Theodorus of

Maastricht. As well as the singing master and the organist there (who)

was also a bass [who] was the third in rang and three other singers that

were not specified, but which almost certainly included a tenor and a

countertenor.

These six professional musicians were assisted by

two musician sacristans (generally former choirboys) and by four extra

free-lance singers (pro 4 cantoribus alienis) whose services were

hired in for high days and feasts. This group of adult musicians was

assisted by six young choirboys who had been trained from an early age

by the singing master. They lived in the Roman cloister, where they were

lodged, fed and taught for free and also received a suitable payment.

They sang not only with the adults but also performed regularly on their

own account. One unusual incident from this viewpoint was their custom

of singing the Gloria laus with the singing master in polyphony

from the top of a platform on the tower of the church of St. Nicholas in

the open air on Palm Sunday.

From the fact of the participation of various groups of musicians, the service for a religious feast of the highest (triplex)

rank such as Corpus Christi took on a singularly different character.

The entire church building was brought into play; what we miss the most

from an acoustic point of view is the rood loft, for at that time it

separated the choir from the transept and the singers would often

perform polyphonic works mounted on it.

For this recording our

choice settled on the feast of Corpus Christi because of the liturgical

richness of this festival. It originated in Liège and was made part of

Catholic ritual by Pope Urban IV, a former archdean of Liège. The office

itself was written by St. Thomas Aquinas and it is celebrated on the

Thursday after Trinity Sunday, the first Sunday after Whitsun.

We

are particularly well informed on how this particular festival was

celebrated in the collegiate church of Tongres, this thanks to the 15th

century Liber Ordinarius that was attached by a chain (Liber catenatus)

to the choir. Later versions from the 17th and 18th centuries also

provided detailed information. It seems, however, that the rites

remained almost unchanged across the centuries; it ran in general as

follows:

Corpus Christi is considered as a feast of triplex

rank, the highest rank of the religious festivals. The bells are rung

and the church is fittingly decorated. The cantor and the canon of the

week (the Hebdomadarius) hold the choir from each side, meaning

that they intone certain chants. The liturgical feast begins the evening

before with the first Vespers that take place on Wednesday at around

2.30pm, with the hymn Pange Lingua and several others being sung.

Compline is then sung.

On the day of Corpus Christi itself Matins

are sung at 5am with the three nocturnes, the bells having been rung

since 4.30am. The lesser Hours begin with Prime at 9am, then with Tierce

followed by High Mass with, amongst other music, the Introit Cibavit eos, the Gloria, the Alleluia Caro mea, the sequence Lauda Sion, the Gospel according to St. John (Caro mea), the Creed, the Offertory Sacerdotes, etc.

Sext

is sung after the Mass, after which the most solemn procession of the

year circulates across the city. During the procession the responses for

the Blessed Sacrament, for the Trinity, for Our Lady, for the angels

and for the other saints are sung. This procession must have been

particularly varied and lively, given the co-operation of the burghers

and the clerks. The corporations marched in front with their respective

leaders, followed by several of the religious orders in Tongres. The

small reliquary was borne in the middle of them by two young chaplains

in turn. The religious orders sang Gregorian chant that alternated with

the polyphonic music sung by the singers of the collegiate church, who

followed the religious orders. After them came two canons who recited

the Epistle and the Gospel for the day. They in turn were followed by

the secular members of the congregation of the Blessed Sacrament with

torches and crucifix, and sometimes by a second group of polyphonic

singers. The other canons and chaplains then advanced with torches,

followed by a choirboy with a bell in his hand. The other boys

surrounded the Blessed Sacrament with thurible, reliquary and lantern.

The dean, processing under a baldachin borne by the members of the

magistracy, displayed the Sacrament. The musicians performed just in

front of the Sacrament, while the general populace (populi turba) brought up the rear.

The

procession covered a large part of the town. It left the church from

the great door of St. Mary Magdalen, crossed the market, turned towards

what was known as the convent with its majestic canons' apartments in

order to arrive, after having passed through the rue de Maestricht, at

the St. Jacques hospital. The procession continued towards the Commerput

and turned via the Kiedelstrote towards the church of St. Catherine in

the Beguinage. The procession then halted at St. John's church. The

antiphon O sacrum convivium was sung as the procession left the

church and then continued via the rue de la Monnaie towards the church

of the Regulars that has since disappeared. The procession then left the

centre of the city via the rue des Chats and the Steenderpoort, passed

through the Kogelstraat, went along the Heymelinghen ramparts, passed

the Hasselt Gate and arrived at the Maastricht gate through the rue du

Sacrement. The procession then returned into the city and continued back

to the principal church, re-entering it on the North side through the

great door of St. Mary Magdalen. The procession halted once more and

when all had arrived the cantor intoned the antiphon Sub tuam protectionem confugimus. The organ and the choir played and sang the Te Deum

in alternation. The clergy returned to the choir; the dean stood at the

entry to the choir and gave the benediction with the Blessed Sacrament.

The Sacrament was then returned to the high altar. The second Vespers

at 2.30 pm were sung as had been the first Vespers of the day before;

the hymn Sacris solemniis, in its setting by Johannes Brassart,

being also sung. The feast day ended with Compline, probably followed by

a hymn of praise.

Our central composer is Johannes Brassart, an

unjustly forgotten master of the first generation of polyphonic

composers who lived in the shadow of Dufay and Binchois. It was long

believed that Brassart was born in Liège or in the Italian town of Lodi,

but following an indication in one of his works it is clear that he was

born in the town of Lauw (de Ludo). The first recorded traces of

Brassart are in the Collegiate Church of St. John the Evangelist in

Liège, where he was named chaplain and ‘succentor’. He lived in Rome

between 1425 and 1426, most probably because of the Jubilee Year. He

later fulfilled various musical functions in the collegiate churches of

St. John the Evangelist and St.Lambert in Liège, going on to win

international renown as both singer and composer through his performing

with Dufay in the Papal chapel (1431) and later at the Council of Basle.

He was rector capelle for the Emperors Sigismund, Albert II and

Frederic III at various periods between 1434 and 1443, composing

official State motets for them. He suffered greatly from homesickness

like many other singers from the Low Countries and wanted to return to

the land of his birth. He was sometimes named canon to the collegiate

church of Our Lady in Tongres and gained the position of canon and

cantor there in 1444-45. He returned to Liège in 1445, where he remained

a canon at St. Paul's until his death in 1455.

The style of

Brassart's music is typical of the so-called Liège School, the central

figure of which was Johannes Ciconia. In contrast to Dufay's music,

Brassart's music was not consciously influenced by the more consonant

English style of John Dunstable. Most of his works are in three parts,

sometimes in four parts; all are highly varied in texture. Given that no

complete Mass by Brassart has survived, for the purposes of this

recording we have put together an ordinarium made up of separate pieces

that embody different styles and contrasting vocal ranges. In the first

place we find the so-called ‘descant-tenor’ style, in which the upper

voice and the tenor are approximately equal and where there is also

space for counterpoint and imitation to flourish. There is also the

frequently adopted treble-dominated style, in which the upper voice

dominates and the lower voices perform a more accompanying function.

There is finally the simple homophonic ‘conductus’ style, in which the

three voices were equal. If a cantus firmus was used then it was usually

to be found paraphrased in the upper voice.

The Te Deum

by Gilles Binchois is set very functionally in a simple faux-bourdon

style and the piece as a whole is old-fashioned in comparison to the

composer's songs. A characteristic of fifteenth-century performance

practice was the alternatim, in which vocal polyphony was alternated

with organ music or Gregorian chant. The organ music of the period is

often characterised by fanciful ornamented passages in the right hand

and the domination of the upper voice, polyphony thereby giving way to

ornamentation.

We can only offer an aural impression of the

complete office, given that it lasted for several hours, and of its many

possibilities of performance and interpretation. The complete

recreation of such an undoubtedly colourful occasion in which liturgy,

music and the visual arts were all closely bound and formed almost a

Gesamtkunstwerk before its time must, however, be left to the

imagination of each individual listener.

Eugeen SCHREURS

(FWO, Alamire Foundation, K.U. Leuven)

Translation : Peter LOCKWOOD