capilla.be

Capilla Flamenca CAPI, 2003

capilla.be

Capilla Flamenca CAPI, 2003

1. Your flight is canceled... [0:41] Joanna Dudley

2. Passione di Giullianello [1:59] Traditional | Christine Leboutte, Damien Jalet, Laura Neyskens

3 [5:07]

· a. Thank you Jesus, I'm alive! | Darryl E. Woods, Ulrika Kinn Svensson, Joanna Dudley

· b. Sus une fontayne | Johannes CICONIA (ca. 1372?-1412) | Capilla Flamenca

4 [6:51]

· a. My grandma developed Alzheimer... | Ulrika Kinn Svensson, Laura Neyskens

· b. Per tropo fede | Anonymous | Christine Leboutte, Capilla Flamenca

· c. She started miming the action of sowing... | Ulrika Kinn Svensson, Laura Neyskens, Darryl E. Woods

5 [7:00]

· a. I'm so sorry, I'm so sorry | Erna Ómarsdóttir

· b. Lulay, lulay | Anonymous | Capilla Flamenca

· c. End of message | Joanna Dudley

6 [5:54]

· a. Oh, my goodness gracious, we're back!... | Darryl E. Woods, Ulrika Kinn Svensson

· b. Gloria: Missa Notre Dame | Guillaume de MACHAUT (ca.1300-1377) | Capilla Flamenca

· c. Did I do that?... / Baby love | W&M: B. Holland, E. Holland (1964) | Darryl E. Woods, Laura Neyskens

7 [3:45]

· a. It's funny because... | Ulrika Kinn Svensson, Laura Neyskens, Joanna Dudley

· b. Or sus vous dormés trop | Anonymous | Capilla Flamenca

8. And sometimes I almost wished... / Isabella [5:30] Anonymous | Capilla Flamenca

9. Hello...? / Riches d'amour [3:53] Guillaume de MACHAUT | Capilla Flamenca

10. Somewhere Over The Rainbow [2:15] Harold Arlen (1905-1986) | Joanna Dudley, Capilla Flamenca

11. Ave Maria [4:52] Traditional | Christine Leboutte, Les Ballets C. de la B., Capilla Flamenca

12 [3:19]

· a. Thou shall not kill | Darryl E.Woods

· b. Beata Mater | John DUNSTABLE (ca. 1390-1453) | Capilla Flamenca

13. Pietà / Mahiu, jugiez [1:54] | Mahieu de Ghent (14th Century) | Capilla Flamenca

14. Yes, Jesus Loves Me [1:40] | Traditional | Lisbeth Gruwez

15. Li Lamenti [5:08] Traditional | Christine Leboutte, Damien Jalet, Les Ballets C. de la B., Capilla Flamenca

16. Hiroshima [1:19] Damien Jalet, Joanna Dudley

17. Sofðu unga ástin mín [6:31]

Traditional | Erna Ómarsdóttir, Joanna Dudley, Christine

Leboutte, Capilla Flamenca

18. Song Qing Lang [3:28] Traditional | Joanna Dudley, Capilla Flamenca

19 [6:38]

· a. Goodbye / Amazing Grace | Traditional | Joanna Dudley, Darryl E. Woods

· b. Ach Vlaendre vrie | Thomas FABRI (fl. 1400-1415 | Capilla Flamenca

Sources:

· Gent Rijksarchief, Fonds varia D 3360;

· Roma Biblioteca Vaticana, Codice Rossi 215;

· Paris Bibliothèque Nationale, f.fr.22.546;

· London, British Library Ms. add. 29987;

· Modena, Biblioteca Estense a.M.5.24

#2: La Passione di Giullanello, Latium: (recording and transcription G. Marini 1975)

— originally sung by the women of Giulianello (45 km south of Rome).

Here a fragment of a long Passion is sung. The song also includes a B-part, not sung here.

#11: AveMaria, Sardinia: (recording and transcription J. Faye 1998)

— version of Orosei (province of Nuora) of the famous Sardinian Ave Maria

which can be found throughout the island, originally sang by brotherhoods.

#15: Lamenti, Sicily: (recording and transcription C. Leboutte 2003)

— A real cry out with Arab characteristics from the village of Grotte (province of Agigento),

for two soloists with responses sung by a choir made up of vil- lagers (men only).

Capilla Flamenca — Dirk Snellings

biography & discography: www.capilla.be

Marnix De Cat: countertenor / percussion

Gunther Vandeven: countertenor

Jan Caals: tenor

Lieven Termont: baritone

Dirk Snellings: bass

Jan Van Outryve: lute

Liam Fennelly: fiddle

Jowan Merckx: recorder and bagpipe

Les Ballets C. de la B. — Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

history: www.cdelab.be

soli: Christine Leboutte, Joanna Dudley, Lisbeth Gruwez, Erna Ómarsdóttir, Damien Jalet

choir: Lisbeth Gruwez, Damien Jalet, Nam Jin Kim, Laura Neyskens, Erna

Ómarsdóttir, Ulrika Kinn Svensson, Nicolas Vladyslav,

Darryl E. Woods, Mark Wagemans

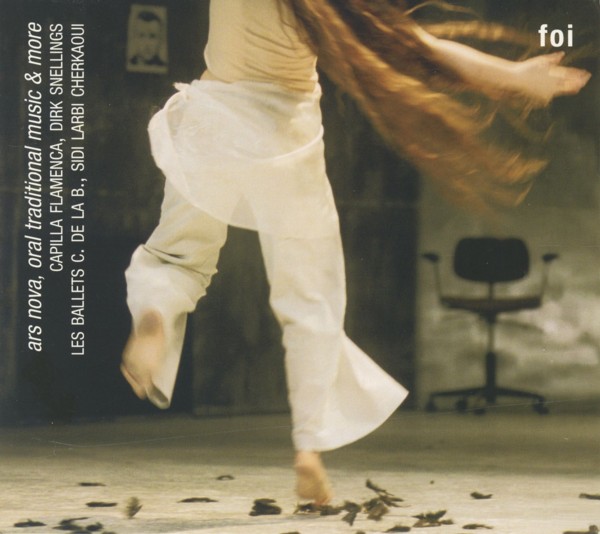

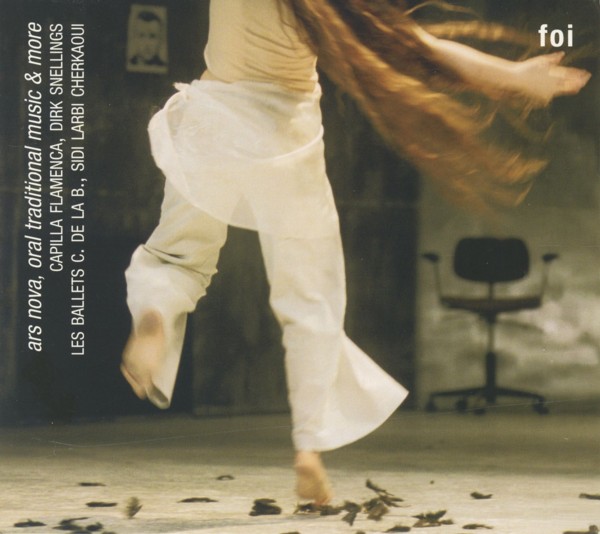

Foi CD production :

· digital recording : Jo Cops

· editing: Jo Cops, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Dirk Snellings

· graphic designer: Michel De Backer

· photographer: Kurt Van der Elst

· production and coordination: An-Heleen De Greef, Merle Barton (Capilla Flamenca)

· musicological research: Dr. Bruno Bouckaert (Alamire Foundation)

· recording: Chapel of the Irish College, Leuven & Ensemblezaal K.U.Leuven in STUK,

17th , 18th of June & 23rd, 24th of July 2003, Belgium

· song translators: Gregory Bull, Merle Banen, An-Heleen De

Greef, Christine Leboutte, Cordelia Spenke, Catherine Thys, Christophe

Van der Vorst.

Foi Dance Production : direction: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

· Ars Nova music: Capilla Flamenca, Marnix De Cat, Jan Guais,

Lieven Termont, Dirk Snellings, Jan Van Outryve, Liam Fennelly, Jowan

Merckx

· musical supervision: Dirk Snellings

· production and tourmanager: Lies Van Borm

· coaching: Christine De Smedt, Isnel Da Silveira

· technical supervision: Koen Bauwens

· scenography: Rufus Didwiszus

· light: Jeroen Wuyts

· sound: Eddy Latine

· stagemanager: Wim Van De Capelle

· costumes: Isabelle Lhoas

· singer and musical supervision of the dancers: Christine Leboutte, Joanna Dudley

· choreography and dance: Joanna Dudley, Lisbeth Gruwez, Damien

Jalet, Nam Jin Kim, Christine Leboutte, Erna Ómarsdáttir,

Laura Neyskens, Ulrika Kinn Svensson, Nicolas Vladyslav, Darryl E.

Woods, Mark Wagemans

· coproducers: Stedelijke Concertzaal De Bijloke Gent,

Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz Berlin, Théâtre de la

Ville Paris, Monaco Dance Forum, Holland Festival Oude Muziek Utrecht

& Springdance/works Utrecht, Vooruit Arts Centre Gent, South Bank

Centre London, Tanzquartier Wien

· thanks to: Die Baguet, Sarah De Ganck, Joris De Zutter, Damien

Jalet, Herwig Onghena, Klaartje Proesmans, Yves Rosseel, Lieven

Thyrion, Wim Van De Capelle.

· tourlist: www.fransbrood.com

This recording has been realised in collaboration with: Capilla

Flamenca, Stedelijke Concertaal De Bijloke & Les Ballets C. de la B.

Foi; overleven en overleveren

De muziek was grotendeels het uitgangspunt bij de ontwikkeling van Foi.

Op een haast toevallige wijze kwamen verschillende parameters samen.

Ten eerste bestond het verlangen verder te werken met mondeling

overgeleverde traditionele gezangen uit Italië, zoals in mijn eerste

voor stelling Rien de rien door zanger/danser Damien Jalet. Vervolgens stelde Yves Rosseel van De Stedelijke Concertzaal De Bijloke voor een dansvoorstelling te maken op basis van 14de-eeuwse Ars Nova muziek uit Gent. Tenslotte was ook het project d'avant,

een zang/dansvoorstelling met als uitgangspunt muziek uit de 10de tot

13de eeuw -a capella gezongen en gecreëerd door Juan Kruz Diaz De Garaio

Esnaola, Luc Dunberry, Damien Jalet en mezelf, een voorbode op Foi.

In Foi worden de 14de-eeuwse Ars Nova muziek, ons bekend dankzij teruggevonden partituren en uitmuntend gebracht door de Capilla Flamenca,

enerzijds en de mondeling overgeleverde traditionele muziek gezongen

door Christine Leboutte, Damien Jalet, Joanna Dudley en de dansers

anderzijds op een eigenzinnige manier met elkaar geconfronteerd. Twee

manieren om de geschiedenis en haar mythes te vertellen, te herhalen en

door te geven aan een volgende generatie. Twee manieren om te overleven

ook, om de tijd en nieuwe tendensen te doorstaan. Twee gelijkwaardige

tradities die elkaar aanvullen.

In de voorstelling werd een link

gelegd tussen de 14de eeuw en nu. Toen had je de pest en de

kruistochten, nu heb je SARS en de oorlog in Irak. De vraag rijst of er

veel veranderd is sinds de middeleeuwen. We kijken met een arrogante

blik neer op de barbarij van toen, maar weigeren soms onze ogen te

openen voor de huidige, analoge wreedheden.

Naast mooie, grappige of eerder serene momenten zijn er ook meer agressieve scènes aanwezig in Foi,

die het publiek haast ongemakkelijk doen voelen; dit om een totaalbeeld

te schetsen van het menselijke gedrag. Binnen al die momenten van

harmonie en geweld is overleven het belangrijkste thema. Deze drang is

bepalend voor de echte betekenis die achter overtuiging schuilt,

meer nog dan geloof of spiritualiteit. Spiritualiteit doet spontaan haar

intrede in de voorstelling daar de muziek, vaak religieus geïnspireerd,

zelfs de meest banale beweging een extra dimensie of betekenis geeft.

In Foi

worden het heden en het verleden ook gelijkwaardig; mythes, legendes

van toen en nu versmelten in het collectief bewustzijn van de

performers. In de middeleeuwen trachtte men met menselijke stemmen het

engelengezang te benaderen. Dit was de inspiratiebron om enkele dansers

als onzichtbare beschermengelen de "echte" personages op scène te

leiden. De complexe gelaagdheid van de muziek wordt vertaald door een

veelheid aan beelden en associaties die elkaar tegenspreken of

aanvullen.

Op het vlak van de symboliek domineert het getal drie:

de Heilige Drievuldigheid, drie religies, drie hoofdstukken, drie ramen

als drieluik, twee hoge muren creëren een driehoek op scène. Vaak werd

ook gewerkt in trio's bij de creatie van het dansmateriaal, met drie ook

als een circulaire beweging, een perpetuum mobile. Drie letters ook

vormen Foi.

Zowel in de geschreven als in de mondelinge

overgeleverde muziek komt het religieuze thema van Maria en haar zoon

Jezus meerdere keren aan bod. Het thema van de Pietà (de moeder die

huilt om de dood van haar zoon) heeft dan ook het creatieproces

geïnspireerd- hoe plots de overlevering kan ophouden als je kind sterft.

Ook andere elementen zoals de terugkeer naar je oorsprong worden

aangeraakt. De geruststellende functie van het slaapliedje Lulay lulay

wordt op een haast mystieke manier verbonden met het wrede Ijslandse

wiegelied van Erna Ómarsdóttir; wat op zich weer een verlenging is van

het thema van de mondelinge overlevering, aangereikt door de dansers.

Ieder verrijkte het concept met z'n eigen verleden en culturele wortels.

Als dit persoonlijk verleden te zwaar begon te wegen, ontstond dan ook

het verlangen zichzelf te herbronnen, zichzelf opnieuw uit te vinden in

een andere cultuur, zoals bijvoorbeeld Joanna Dudley in het verrassende

Chinese lied Song Qing Lang.

De performers komen uit Korea, de V.S., Zweden, België, Frankrijk, Ijsland, Australië... en ook de muziekselectie

draagt

misschien het vaandel van het geloof in multiculturaliteit. We

trachtten vooral om, binnen deze verscheidenheid, het gemeenschappelijke

element van het mens-zijn te onderstrepen, met zijn mooie en minder

mooie kanten. Zo ook dient Ach Vlaendre vrie, waarbij de zangers

zich uiteindelijk bij de dansers op de grond voegen, niet als

flamingantisch of nationalistisch te worden geïnterpreteerd, maar eerder

als een oprechte en eerlijke terugkeer naar de oorsprong, zo eigen en

persoonlijk dat het universeel wordt ervaren.

SIDI LARBI CHERKAOUI

Ars Nova en Trecento muziek in Europa tijdens de 14de eeuw.

De middeleeuwen worden weleens de donkere tijden van onze Westerse beschaving genoemd omdat ze zich

localiseren

tussen de bloeiende Romeinse tijd en de heropstanding van deze

klassieke idealen tijdens de Renaissance. Deze uitspraak is misschien

van toepassing op de periode van verval en ontreddering als West-Europa

een ontvoogdingsstrijd voert tegen de Romeinen. Maar zodra dit evenwicht

is hersteld en de feodale structuren zijn geïnstalleerd slaagt de hoge

adel erin door een centralisatie van middelen en macht een hoogstaand en

uitzonderlijk luxueus en verfijnd leven te leiden dat we vandaag

typeren als de gotiek.

Vanuit Frankrijk overstroomt deze nieuwe (levens)kunst (Ars Nova) die alle stroeve en logge structuren van het verleden (Ars Antiqua)

openbreekt, heel Europa. Het Franse model kent in Italië veel navolging

bij de hoge adel en de rijke kooplui in de loop van de 14de eeuw, maar

blijft gebed in de eigen (muzikale) traditie (Trecento).

Net

zoals in de gotische kathedralen alle muren worden opengebroken zo

verkent de muziek voor het eerst de autonomie van elke muzikale fijn. In

de polyfone (meer stemmige) ontdekkingstocht van de 14' eeuwse

toondichters krijgt vooral de tijdsbeleving een ongekende verfijning en

complexiteit. Waar in de Ars Antiqua muziek de stemmen synchroon (homofoon) verlopen krijgt in de Ars Nova iedere stem haar eigenheid in een strikt rollenpatroon dat het sterkst tot uiting komt in de isoritmische

(staats)motetten. Door het bijzonder geraffineerd omgaan met de

tijdsindeling van elke partij ontstaat er een ritmische complexiteit die

in de West-Europese muziek nooit meer zal geëvenaard worden.

In Italië heeft de Trecento

componist vooral oog voor uitbundige virtuositeit en nieuwe

samenklanken. De versmelting van de beide stromingen omstreeks 1400

leidt tot een bijzonder verfijnde toontaal (Ars subtilior) die

her en der in Europa aan bepaalde hoven tenzeerste wordt gecultiveerd.

Ook in Vlaanderen bleef men niet ongevoelig voor de muzikale

vernieuwingen zodat in de grootstad bij uitstek Gent heel wat werken

opduiken die deze Europese stroming een eigen locale invulling geven.

Tijdens

de ‘Foi’ voorstelling zullen alle dimenties van de 14de eeuwse muziek

een plaats krijgen met zowel de “geleerde” muziek of genoteerd muziek in

misdelen, motetten, hoofse liederen (ballade, virelai, rondeau) en hoof

se dansen als de “simpele” niet genoteerde muziek die in orale

tradities is verder blijven bestaan tot vandaag.

Deze

verscheidenheid staat borg voor een gevarieerd aanbod dat de toeschouwer

van vandaag niet alleen kan verbazen maar ook emotioneel en spiritueel

kan raken.

DIRK SNELLINGS

La musique traditionnelle italienne

Ces

trois chants de tradition orale présentés ici sont issus du répertoire

très riche de la Semaine Sainte en Italie. Ils sont transmis encore

aujourd'hui dans les villages du sud par des chanteurs non

professionnels lors des processions de Pâques.

Bien que fort

différents dans leur structure, on relève dans leur mode d'exécution les

mêmes caractéristiques esthétiques propres au chant de la campagne , et

qui les distinguent de la musique savante: voix poussée- sans recours à

la voix de tête, rythme peu rigide, système non tempéré avec mélismes à

l'appréciation du soliste, coda longue et souvent rinforzando

avant la fin. C'est un chant rituel lié à une

communauté et qui a une fonction - ici raconter la Passion du

Christ.

Le

collectage de ces chants est toujours en cours (notamment par des

anciens élèves des cours d'ethnomusicologie appliquée dispensés par

Giovanna Marini à l'Universite de Paris VIII de 1990 à 2000).

Remarques:

Il

est très difficile de dater l'origine de ces chants car il n'existe, au

départ, ni partitions ni textes écrits ; les jeunes des villages

apprennent sur le tas en se mêlant aux anciens.

Plus que la

mélodie ou le texte, c'est le type de sons, le timbre, la couleur qui

sont transmis ; les voix pouvant aller jusqu'à imiter le son des animaux

( chèvre, brebis,...) dans le cas des chants de bergers sardes.

Certains

chants liés au monde du travail ont déjà disparus et c'est dans le

cadre paraliturgique que l'on retrouve le plus large répertoire toujours

vivant. Même si : « Le clergé voit souvent d'un très mauvais œil

l'interprétation de ces chants traditionnels (en dialecte) dans les

églises. L'Eglise tend à leur substituer des chants modernes en italien,

composés perdes musiciens catholiques autorisés. » dixit Macchiarella.

Cette

façon de chanter - haut et fort/ici et maintenant - représente donc un

moment de reconnaissance pour les membres d'une communauté et « n'est en

aucun cas, pour ceux qui la pratique, une évocation nostalgique du

passé ». Il réaffirme simplement le fait de vivre au sein d'un groupe et

la volonté de partager les moments forts des périodes de fête.

CHRISTINE LEBOUTTE

Bibliographie et discographie voir MACCHIARELLA, I., Voix d'Italie, Actes Sud, 1999. Voir aussi http://muslcaitalia.free.fr

Foi: survival and tradition

Music was to a large extent the point of departure in the development of Foi.

Different parameters came together in an almost random way. In the

first place there was the desire to delve further into orally

transmitted, traditional vocal music from Italy, as in my first

performance, Rien de rien, by singer/dancer Damien Jalet. Yves Rosseel, from the Civic Concert Hall De Bijloke (Ghent) then proposed a dance production based on 14th-century Ars Nova music from Ghent. Finally there was the project d'avant,

a vocal/dance performance drawing on 10th- to 13th-century music, sung a

capella and premiered by Juan Kruz Diaz De Garaio Esnaola, Luc

Dunberry, Damien Jalet and myself; this latter work was a forerunner of Foi.

In Foi,

there is a confrontation between 14th-century music of the Ars Nova,

known to us through rediscovered scores and splendidly performed by the Capilla Flamenca,

on the one hand, and orally transmitted traditional music, sung by

Christine Leboutte, Damien Jalet, Joanna Dudley and the dancers, on the

other. Two ways of recounting, repeating and recreating history and its

myths for a new generation. Two ways of surviving, allowing the music to

stand the test of time and new ideas. Two equally-matched traditions,

complementing one another.

In the performance, a link is made

between the 14th century and today. In those days there was the pest and

the crusades, now there is SARS and the war in Iraq. The question

arises of whether so very much has changed since the Middle Ages. We

look back condescendingly at their ‘barbarism’, while sometimes refusing

to open our eyes to the analogous brutalities of the present-day.

Besides beautiful, funny or more calm moments, there are more aggressive scenes in Foi,

which could make the audience feel somewhat uncomfortable. The idea is

to sketch a complete picture of human behaviour. Within all these

moments of harmony and violence, survival is the most important theme.

This urge is crucial for the true meaning hidden in the word conviction

- even more than belief or spirituality. Spirituality spontaneously

enters into the performance, as this music, often religious in

inspiration, often gives an extra dimension to even the most banal

movements.

In Foi, the present day and the past are thus

put on an equal footing; myths, legends of old and of today melt

together in the collective consciousness of the performers. In the

Middle Ages, an attempt was made to approximate the songs of the angels

with the human voice. This was the source of inspiration for the dancers

who, like invisible guardians, guide the ‘real’ characters around the

stage. The complex layering of the music is translated by a multiplicity

of images and associations that both contradict and complement one

another. On the level of symbolism, the number three dominates: the Holy

Trinity, three religions, three chapters, three windows acting as a

triptych, and a triangular stage created by two high walls. The creation

of the dance sequences often also takes place in groups of three,

forming a circular movement, a perpetuum mobile. Three letters also form

the name of the performance, Foi.

The religious theme of

Mary and her son Jesus is central to the music of both the written and

oral traditions. The theme of the Pietà (the mother weeping over the

death of her son) did indeed inspire the process of creation — how

suddenly can the death of a child break off the process of transmitting

tradition. Other themes, such as the return to one's roots, are also

touched on. The comforting function of the lullaby Lulay lulay is

linked almost mystically to Erna Ómarsdóttir's cruel lullaby; this is

in itself a continuation of the theme of oral tradition, as put forward

by the dancers. Each dancer enriches the concept with his or her own

past and cultural roots. When this personal past becomes too heavy to

bear, there emerges the desire to rejuvenate oneself, reinvent oneself

in another culture, as Joanna Dudley does remarkably in the Chinese

song, Song Qing Lang.

The performers come from Korea, the

United States, Sweden, Belgium, France, Iceland and Australia, while the

musical selection could also be seen to be a reflection of a belief in

multiculturalism. Within this diversity, we have in the first place

attempted to underline the shared element of the human experience,

showing both its beautiful and less beautiful sides.

The song, Ach Vlaendre vrie,

in which the singers finally join the dancers below on the floor, thus

need not be interpreted as an expression of Flemish nationalism, but

rather as a sincere and honest return to the source, so distinctive and

personal that it can be experienced as universal.

SIDI LARBI CHERKAOUI — TRANSLATED BY STRATTON BULL

Ars Nova and Trecento music in 14th-century Europe

The

Middle Ages are often called the ‘Dark Ages’ of our Western

civilisation, situated as they are between the blossoming of the Roman

period and the revival of these classical ideals during the Renaissance.

This view is perhaps applicable to the period of decline and fall, when

Western Europe fought its struggle of emancipation against the Romans.

However, once balance had been restored and feudal structures put in

place, the high nobility were successful in centralising their resources

and power to create a grandiose and exceptionally luxurious and refined

way of life, today referred to as Gothic.

Originating in France, this new art (of living) - Ars Nova - spread throughout Europe, breaking wide open all the stiff and ponderous structures of the past (Ars Antiqua).

The French model was eagerly adopted by the nobility and affluent

bourgeoisie in 14th-century Italy; that model was now, however, embedded

in that country's native (musical) tradition (Trecento).

In

the same way that the walls of the Gothic cathedrals were broken open,

music now explored for the first time the autonomy of each musical line.

In this polyphonic voyage of discovery undertaken by 14th-century

composers, it was particularly the organisation of time that went

through an unprecedented process of refinement and complexity. Whereas

in Ars Antiqua, all voices were synchronised (homophony), in the Ars Nova, each voice was accorded its own characteristics in a strict pattern of roles most clearly evident in isorhythmic (occasional) motets.

Through the highly refined treatment of each part's temporal

subdivisions, a rhythmic complexity was created, the like of which

Western-European music would never again equal.

In Italy, the composers of the Trecento

were chiefly interested in brilliant virtuosity and new harmonies. The

coming together of the two streams around 1400 led to a highly-refined

tonal language (Ars subtilior), which was meticulously cultivated at certain courts around Europe.

In

Flanders, too, this musical innovation left its mark. In Ghent, the

great urban centre of the region, a great many works have been found,

local versions of this Europe-wide movement.

All the dimensions

of 14th-century music are heard in the course of the performance of

‘Foi’, including both ‘learned’ (notated) music, as found in mass

movements, motets, courtly songs (the ballade, virelai and rondeau) and

courtly dances, and ‘simple’ (non-notated) music, which has come down to

us in oral traditions.

This diversity guarantees a varied

selection of music that continues not only to captivate us today as

listeners, but can also touch us emotionally and spiritually.

DIRK SNELLINGS — TRANSLATED BY STRATTON BULL

Traditional Italian Music

The

three songs from the oral tradition heard on this recording form part

of the rich repertoire of music for Holy Week in Italy. They continue to

be transmitted today in the villages of southern Italy, sung by

non-professional singers in Easter processions.

Although the

songs are very different in structure, the same aesthetic

characteristics - typical of rural singing, thus distinguishing them

from “learned” music - are found in their performance: somewhat forced

voices with no use of the head voice, very flexible rhythm, an

untempered system with melismas added at the whim of the performer, long

codas and often a rinforzando towards the end of a song. These

are songs of ritual, connected to a community and with a specific

function - here the telling of the story of Christ's Passion.

These

songs are at present still being collected (in particular, by former

students of the Applied Ethnomusicology course taught by Giovanna Marini

at the University of Paris VIII from 1990 to 2000).

Remarks:

It

is very difficult to date the origin of these songs, in the first place

because there are no scores or written texts to speak of: the young

people in the villages learn as they go by performing together with the

older singers. More than the melody or the text, it is the type of

sounds, the timbre and the colour that are passed down: in the songs of

Sardinian shepherds, the voices even go as far as imitating the sound of

animals (goats, sheep...).

Certain songs connected to the world

of work have already disappeared; the para-liturgical realm is the major

source for extant repertoire - this despite the fact that (as

Macchiarella points out) “the clergy often look very disparagingly upon

the performance of these traditional songs (in dialect) in the churches.

The Church tends to replace them with modem songs in Italian, composed

by authorised Catholic musicians.”

This manner of singing - loud

and clear/here and now - thus represents a moment of recognition for the

members of a community and “is in no way, for those who practise it, a

nostalgic evocation of the past”. It reaffirms simply the fact of living

in the midst of a group and the will to share important moments during

festive periods.

CHRISTINE LEBOUTTE — TRANSLATED BY STRATTON BULL

For bibliography and discography, see MACCHIARELLA, I., Voix d'Italie in Actes Sud, 1999. See also http://musicaitalia.free.fr