Jacob Obrecht / Capilla Flamenca | Piffaro

Chansons | Songs | Motets

medieval.org

capilla.be

Eufoda 1361

2005

't VROEDE, the SAGE, le SAGE

Jacob OBRECHT

1. Sullen wij langhe in drucke moeten leven [1:13]

2. Ave Regina caelorum [3:43]

Marco DALL'AQUILA

3. Recercar [2:23]

Jacob OBRECHT

4. Fors seulement l'attente que je meure [8:22]

5. Instrumentaal (Tekstloos 3) [1:56]

6. Marion la doulce [2:06]

7. Beata es, Maria [3:48]

8. Instrumentaal (Tekstloos 1) [1:35]

't ZOTTE, the FOOL, le FOL

Jacob OBRECHT

9. Weet ghij wat mijnder jongher herten deert [2:07]

10. Se bien fait [2:28]

11. Ic weinsche alle scoene vrauwen eere [2:14]

12. Wat willen wij metten budel spelen [2:12]

13. Waer sij di Han? Wie roupt ons daer? [2:08]

14. Meiskin es u cutkin ru? [2:17]

15. Rompeltier [2:14]

16. Als al de weerelt in vruechden leeft [1:49]

't AMOUREUZE, the LOVER, l'AMOUREUX

Jacob OBRECHT

17. Instrumentaal (Tekstloos 4) [1:39]

18. Laet u ghenoughen liever Johan [2:01]

Tandernaken al op den Rin

19. Antwerps Liedboek [1:13]

20. Jacob OBRECHT [2:39]

21. Hans NEUSIDLER [4:07]

Jacob OBRECHT

22. Magnificat [8:13]

23. Ave maris stella [1:42]

CAPILLA FLAMENCA

Dirk Snellings

Marnix de Cat, contratenor, percussie

Jan Caals, tenor

Lieven Termont, bariton

Dirk Snellings, bas

Jan van Outryve, luit

Thomas Baeté, viola da gamba

Piet Stryckers, viola da gamba, draailier

PIFFARO

Joan Kimball & Robert Wiemken

Rotem Gilbert, blokfluit, schalmei

Grant Herreid, luit

Greg Ingles, bazuin

Joan Kimball, blokfluit, schalmei

Robert Wiemken, blokfluit, schalmei, percussie

Tom Zajac, blokfluit, bazuin

Dirk Snellings

muzikale leiding

Digitale opname en montage: Jo Cops Productions

Abdij van 't Park, september 2004

Artistieke leiding en concept: Dirk Snellings

Musicologische toelichting: Bruno Bouckaert

Grafische vormgeving: Daniel Peetermans

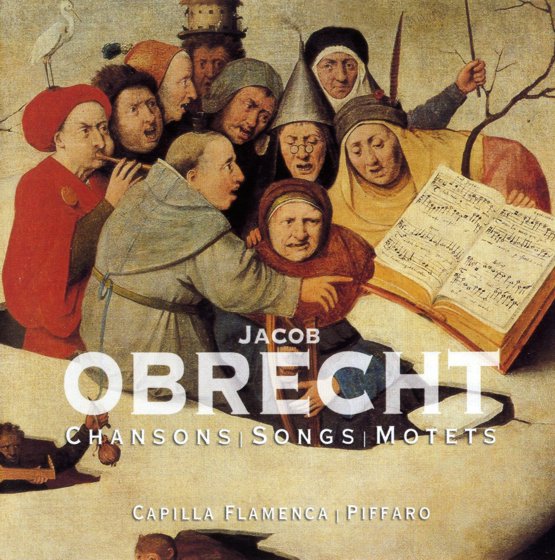

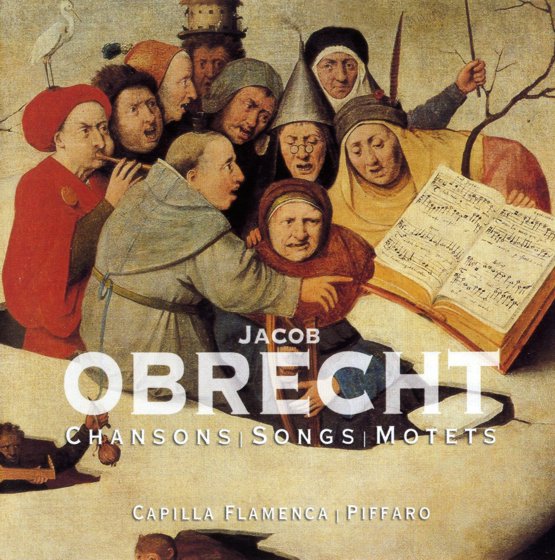

Coverillustratie: Hieronymus Bosch, Het concert in het ei (detail)

Lille, Musée des Beaux-Arts

(foto: ©: RMN/Jacques Quecq d'Henripret)

© 2005 Davidsfonds/Eufoda, Leuven

English liner notes

Jacob Obrecht: Varietas polyphoniae

Jacob Obrecht mag al geruime tijd op de belangstelling van de Capilla Flamenca rekenen omdat hij als geen ander op meesterlijke wijze alle genres van zijn tijd schijnbaar zonder enige moeite bespeelt en bovendien als eerste zoveel meerstemmige zettingen van Vlaamse liederen nalaat. De 500ste verjaardag van zijn overlijden is dan ook een ideale aanleiding om een cd integraal aan deze Gentse polyfonist te wijden.

In het oeuvre van Obrecht merken we overduidelijk dat hij, als haast elke Franco-Vlaamse polyfonist, leeft en werkt op de grens van twee grote culturen: de Franse en de Germaanse. De melancholische, delicate Franse stijl horen we in zijn Franse chansons, terwijl de Vlaamse liederen speels en zelfs pikant uit de hoek komen. In zijn omvangrijk religieus oeuvre levert hij een belangrijke bijdrage tot de ontwikkeling van de polyfone taal in Europa.

Dankzij puik werk van verschillende musicologen in de Nieuwe Obrecht Editie komen we een aantal verloren gewaande liedteksten op het spoor. Voor het eerst reconstrueert de Capilla Flamenca zo enkele Vlaamse liederen in een vocale bezetting.

Andere liederen blijven zuiver instrumentaal daar enkel hun titel gekend is en bovendien nauw aansluiten bij het pittige klankidioom sands luide blaasinstrumenten die Jacob Obrecht, dankzij zijn vader de bekende trompettist Willem Obrecht, bijzonder goed kende.

Het ‘speelmannen’-ensemble Piffaro (US) is zo de ideale partner voor de Capilla Flamenca om U te laten genieten van het bijzonder gevarieerde werk van Jacob Obrecht dat 500 jaar later ons blijft verrassen.

Capilla Flamenca team

Capilla Flamenca team

De profane muziek van Jacob Obrecht

[1457/58—1505]

BRUNO BOUCKAERT

Dans

Ies Chansons d'Obrecht nous trouvons une verve et un esprit tout

différent... on aurait tendance à les croire d'un autte compositeur.

Cependant Obrecht, assez bohème, a connu des gens simples, paysans et

petits bourgeois et compris leur humour, leur goût, leur gaieté, vécu

leurs dé(c)lassements. Quand on écoute les chansons profanes d'Obrecht,

on revit les peintures de Pieter Breughel leVieux... Met deze

omschrijving typeerde de Nederlandse muziekhistoricus L.G. van Hoorn al

enkele decennia geleden op een bijzonder treffende manier het profane

oeuvre van Jacob Obrecht (° Gent 1457/58 - † Ferrara 1505). De beroemde

muziektheoreticus Johannes Tinctoris, die de Gentse componist in zijn

tractaat Complexus effectuum musices een plaats gaf iri zijn

persoonlijke 'top-tien' van de belangrijkste polyfonisten, merkte reeds

op dat Obrechts werk niet alleen in kerken en paleizen weerklonk, maar

ook in de huiskamers van gewone burgers. Hiermee refereert hij

onge-twijfeld aan de chansons en liederen van de componist. Het is een

rijk repertoire dat in het verleden misschien iets minder in de

belangstelling stond, maar in deze CD-opname een centrale plaats krijgt.

Obrecht, vooral gekend en geprezen omwille van zijn monumentale en

magistrale miscomposities, laat zich in deze vaak kleine, maar bijzonder

pittige werkjes van een geheel andere kant zien. De titels van zijn

wereldlijke liederen als Meiskin es u cutkin ru?, Laet u ghenoughen lieverJohan

roepen meteen de sfeer op van "volkse" scènes. Ze voorspel-len guitige

en amusante vertellingen, zij het heel vaak met een belerende ondertoon.

Andere teksten zijn dan weer eerdec hoofs getint (Ic weinsche alle sroene urauwen eere, Marion la doulce) of melancholisch van aard (Sullen wij Ianghe in drucke moeten leven, Weet ghij wat mijnder jongher herten deert).

De vergelijking met de realistische en satirische, maar ook wel

moraliserende genreschilderkunst van Breughel de Oude mag haast

lenerlijkworden genomen. Eén van Obrechts composities wordt immers

afgebeeld op het schilderij 'De verloren zoon' van de Aalsterse schilder

Pieter Coecke (1502-1550), Breughels schoonvader en tevens leermeester.

Het tafereel is heel typerend: de verloren zoon zit in een herberg

tussen twee musicerende vrouwen van lichte zeden en krijgt het

gezelschap van de waardin en een zot; op de achtergrond jagen de vrouwen

hem met stokken weg wanneer zijn geld op blijkt te zijn. Op de tafel

voor de man ligt de superiuspartij van Obrechts heel toepasselijke lied Wat willen wy metten budel spelen, ons ghelt es uut.

In

zijn wereldlijke oeuvre heeft Obrecht zich, méér dan wie ook van zijn

generatiegenoten, toegelegd op het Nederlandse polyfone lied. Zonder

twijfel geldt hij als één van de meest briljante pioniers van het genre.

In totaal zijn er van deze Vlaamse meester éénentwintig liederen bekend

(waaronder drie composities die ook aan andere componisten worden

toegeschreven). In de huidige literatuur is het evenwel niet steeds

duidelijk of al deze composities effectief aan Obrecht dienen te worden

toegeschreven.

Opmerkelijk is de ruime internationale verspreiding

van deze liederen. Eén van de belangrijkste bronnen is een handschrift

dat bewaard wordt in de kathedraal van Segovia (Archivo Capitular de la

Catedral, MS s.s.). Het dateert van ca. 1500 en werd vermoedelijk

vervaardigd aan het hof van de 'katholieke koningen' Ferdinand van

Aragon en Isabella van Castilië. Met niet minder dan zestien van de in

totaal drieëndertig Nederlandstalige composities is Obrecht in deze bron

dé centrale figuur. Vele werken zijn unica en dus in geen enkele andere

bron overgeleverd. Wellicht bereikten deze composities het Spaanse hof

via Ferrara, waar Obrecht op uitdrukkelijk verzoek van Ercole d'Este in

1487/88 verbleef. De hertog moet één van zijn grootste bewonderaars zijn

geweest, want hij bood hem in juni 1504 het aantrekkelijke ambt aan van

maestro di cappella. Obrecht zou zijn broodheer, die in januari

1505 stierf, slechts luttele maanden overleven. In juli van hetzelfde

jaar werd hij één van de vele slachtoffers van de pestepidemie, de zo

gevreesde Zwarte Dood. Na een ietwat grillige carrière werd Ferrara zijn

laatste rustplaats, ver weg van zijn vaderland. De aanwezigheid van

Obrecht (en van talrijke andere Franco-Vlaamse componisten) in Italië,

verklaart ook het groot aantal Italiaanse bronnen waarin zijn

Nederlandse liederen zijn opgenomen, onder meer in diverse Florentijnse

manuscripten en in de eerste muziekdrukken die Ottaviano dei Petrucci

vanaf de vroege zestiende eeuw op de markt bracht.

Enigszins

problematisch is het feit dat in vele gevallen slechts een incipit of

enkel de eerste regel van de liedtekst voorhanden is; doorgaans

ontbreken de volledige teksten. In sommige gevallen kan de vocale versie

wel gereconstrueerd worden aan de hand van concordante bronnen, zoals

in Meiskin es u cutkin ru? en Rompeltier (beide op basis

van een Florentijnse bron met anonieme meerstemmige zettingen op

eenzelfde of nauw verwante tekst). De tekst van het droefgeestige Weetghij wat mijnder jongher herten deert kon worden achterhaald via een anonieme zetting (gebaseerd op Obrechts tenormelodie) in de Brussels-Doornikse stemboekjes.

Toch

blijkt het veelal om instrumentale versies te gaan van de

oorspronkelijke liederen. Dat was overigens een courante praktijk

waarvoor archivalische bronnen talrijke aanwijzingen bevatten. Aan het

Ferrarese hof bijvoorbeeld waren er, naast de Vlaamse en Franse zangers,

veel Italiaanse en Duitse instrumentalisten, vooral blazers, actief

Hierdoor ontstond er een unieke wisselwerking tussen de vocale en

instrumentale tradities. De Venetiaanse trompetter Giovanni Alvise

schreef in 1495 een brief aan de Francesco Gonzaga, hertog van Mantua,

waarin hij meldde werken van Obrecht te hebben bewerkt voor vijf of zes

blazers. Het was bovenal een gebruik waarmee Obrecht zelf, als zoon van

een Gents stadstrompetter, ongetwijfeld zeer goed vertrouwd was. Deze

musici voerden niet alteen vocale werken instrumentaal uit, maar

improviseerden evenzeer op bestaande melodieën, die als

cantus-firmus-tenores het fundament van een compositie vormden. Obrecht

vertrekt dan ook vaak vanuit dit muzikale compositieprocédé. lllustraief

in dat opzicht is het bijzonder populaire [/i]Tandernaken al op den

Rijn[/i], een lied waarin twee vriendinnen een gesprek voeren dat

afgeluisterd woedt door de minnaar van één van hen. Tekst en melodie

zijn onder meer overgeleverd in het Antwerps liedboek. In zijn

driestemmige versie plaatst Obrecht de oorspronkelijke

(volkslied-)melodie in de tenor. De andere partijen bouwen hierrond een

levendig contrapuntisch weefsel. Ook in de tekstloze werken en in de Fuga

vertrekt de componist van een (doorgaans niet geïdentificeerde)

cantus-fırmus. Deze wordt in lange notenwaarden in één van de partijen

of op een canonische manier verwerkt. Mogelijk betreft het hier

instrumentaal bewerkte passages uit miscomposities.

Sommige

liederen en chansons zijn op stilistisch vlak hun tijd vóór en vertonen

reeds enkele kenmerken van het latere Parijse chanson. Het zijn vaak

spitsvondige, frisse en ongecompliceerde werkjes gekenmerkt door

spaarzaam gebruik van imitatief contrapunt, waarbij homofone en

declamatorische passages gecombineerd worden met een eenvoudige

harmonische taal. Soms ontspint zich een dialoog tussen de verschillende

partijen, al dan niet in stemparen. Zo worden de supeeius- en

tenorpartij in Waer sij di Han? in de altus en bas beantwoordt met de vraag Wie roupt ons daer? Tussen altus en tenor in Meiskin es u cutlán ru?

speelt zich een een soort 'dialoog in het zotte' af tussen een man en

een vrouw. De melodie weerspiegelt af en toe de gemoedsuitdrukking van

de tekst. In Weet ghij wat mijnder jongher herten deert

weerspiegelen de dalende lijnen in de superius en het lage register het

treuren van de minnaar, hetgeen contrasteert met een stijgende

melodische lijn naar de hoogste noot op als een donderslach.

Allicht

zijn Obrechts Nederlandstalige liederen ontstaan toen hij actief was in

de Lage Landen: in Bergen op Zoom, Brugge, Antwerpen of Kamerijk, waar

hij als sanghmeestere in dienst stond van de plaatselijke

kerkelijke instellingen. Stuk voor stuk waren het bruisende steden, waar

het gonsde van de activiteit en waar de stedelijke en burgerlijke

muziekcultuur bij uitstek tot ontplooiing kwam. Een deel van de liederen

was mogelijk bestemd voor refreinfeesten, toneelopvoeringen,

zinnespelen en liederenwedstrijden die door de vele rederijkerskamers

werden georganiseerd. De koralen van de Brugse Sint-Donaaskerk waren

hierbij onder Obrechts voorganger, Alianus De Groote, zelfs zeer actief

betrokken. Als al de weerelt in vruechden leeft is waarschijnlijk gebaseerd op een rederijkersgedicht. Andere liederen waren wellicht bedoeld als Spielmusik voor de stadsspeellieden.

Traditioneel

was natuurlijk het Frans de taal bij uitstek van het wereldlijke

meerstemmige repertoire. Het hoeft dan ook geen verwondering te wekken

dat ook Obrecht zich hierop heeft toegelegd. Voor het vierstemmige Fors seulement I'attente que je meure

baseerde hij zich op Ockeghems gelijknamige driestemmige rondeau. De

superiuspartij van Ockeghem wordt als cantus fırmus gebruikt en de

tenormelodie verschijnt bij Obrecht in de superius. Ook hier ontbreekt

de tekst in de bronnen, maar kon een vocale versie worden

gereconstrueerd. Obrecht sluit tevens aan bij de nieuwe tendens om in de

chansons populaire volksliedmelodieën te gebruiken.

Deze opname

bevat ten slotte ook nog enkele religieuze motetten en liturgische

composities. Zoals in de meeste motetcomposities van Obrecht, overheerst

hier de mariale thematiek. De functie van deze werken dient gesitueerd

binnen de collegiale kerken waar hij actief was en waar dergelijke

Mariamotetten in de dagelijkse lofdiensten werden uitgevoerd. De cantus

firmi van Ave maris stella en Beata es, Maria zijn ontleend aan monofone Latijnse Mariagezangen. In het tweede deel van Beata es, Maria worden daarenboven in de alt en tenor tekst én melodie van de sequentia Ave Maria gratia plena toegevoegd. Voor het Ave regina caelorum

baseerde Obrecht zich op het gelijknamige motet van de Engelse

componist Walter Frye. Hij citeert de tenor haast letterlijk, terwijl de

superiuspartij gebaseerd is op de bekende Maria-antifoon. Over de

toeschrijving van de alternatim-zetting van het Magnificat zijn de meningen verdeeld omdat het stilistisch afwijkt van Obrechts ander werk.

Bruno Bouckaert is post-doctoraal onderzoeker voor het Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek

Jacob Obrecht: Varietas polyphoniae

Jacob Obrecht has for some time been a central figure for the Capilla Flamenca, unequalled as he was in effortlessly mastering all the genres of his time and also being the first composer to provide us with so many polyphonic settings of Flemish songs. The 500th anniversary of his death is thus an ideal chance to devote a CD recording to this Ghent polyphonist.Obrecht's work reveals how he, like almost every Franco-Flemish polyphonists, lived and worked in the borderlands between two major cultures, the French and the Germanic. The melancholy, delicate French style is heard in his French chansons, while the Flemish songs are playful and even racy. In his extensive sacred oeuvre, he made a significant contribution to the development of the polyphonic language in Europe.

Thanks to the first-rate work of a number of musicologists in compiling the New Obrecht Edition, we have been able to track down a number of song texts lost until recently. Capilla Flamenca is thus the first ensemble to reconstruct several of these Flemish songs in a vocal setting. Other songs have remained purely instrumental since only their title has been preserved and they closely match the strong sound-idiom of the loud wind instruments that Jacob Obrecht would certainly have known well, thanks to his father, the renowned trumpet player, Willem Obrecht.

The “town waits” ensemble Piffaro (USA) is the ideal partner for the Capilla Flamenca, giving you a chance to enjoy to the full the highly varied work of Jacob Obrecht, which continues to astonish some 500 years later.

Capilla Flamenca team

translation, Stratton Bull

The Secular Music of Jacob Obrecht

[1457/58—1505]

BRUNO BOUCKAERT

Dans

les Chansons d'Obrecht nous trouvons une verve et un esprit tout

différent... on aurait tendance à les croire d'un autre compositeur.

Cependant Obrecht, assez bohème, a connu des gens simples, paysans et

petits bourgeois et compris leur humour, leur goût, leur gaieté, vécu

leurs dé(c)Iassements. Quand on écoute les chansons profanes d'Obrecht,

on revit les peintures de Pieter Breughel le Vieux... With this

description, written some decades ago, the Dutch music historian L.G.

van Hoorn very nicely characterised the secular music of Jacob Obrecht

(° Ghent 1457/58 - † Ferrara 1505). The famed music theoretician

Johannes Tinctoris, who in his treatise Complexus effectuum musices

placed the Ghent composer in his personal 'top ten' of most important

polyphonists, made the observation that Obrecht's work was to be heard

not only in churches and palaces, but also in the houses of the average

bourgeoisie. He was here no doubt referring to the chansons and songs by

the composer. This is a rich repertoire that in the past has perhaps

gained less attention, but on this CD recording takes a central place.

Obrecht, best known and praised for his monumental and magisterial mass

compositions, reveals a very different side of himself in these often

small but very pithy works. The titles of secular songs like Meiskin es u cutkin ru?, Laet u ghenoughen liever Johan,

immediately conjure up 'folk' scenes. They hold out the promise of

roguish and amusing tales, albeit often with a pedantic undertone. Other

texts, however, have a courtly air (Ic weinsche alle scoene vrauwen eere Marion la doulce) or are melancholy in nature (Sullen wij langhe in drucke moeten leven, Weet ghij wat mijnder jongher herten deert).

The comparison with the realistic and satiric but also moralising genre

painting of Brueghel the Older can be interpreted almost literally

here.

One of Obrecht's compositions is even depicted in the painting

'The Prodigal Son' by the Aalst painter Pieter Coecke (1502-1550),

Breughel's father-in-law and teacher. It is a classic scene: the

prodigal son is sitting in a hostel between two music-making women of

dubious reputation, accompanied as well by the innkeeper's wife and a

fool; in the background, the women chase him off with sticks when it

transpires that his money is all gone. On the table in front of the man

lies the superius part of Obrecht's very appropriate song, Wat willen wy metten budel spelen, ons ghelt es uut.

In

his secular oeuvre Obrecht concentrated more than any of his

generational contemporaries on the Dutch polyphonic song. He may without

hesitation be reckoned among one of the most brilliant pioneers of the

genre. In total, 21 songs in Dutch by this Flemish master are known

(including three compositions also attributed to other composers). In

the present literature it is, however, not always clear whether all

these compositions may safely be attributed to Obrecht.

Particularly

remarkable is the wide international dissemination that these songs

enjoyed. One of their most important sources is a manuscript held in the

cathedral in Segovia (Archivo Capitular de la Catedral, MS s.s.). It

dates from ca. 1500 and was probably made at the court of the 'Catholic

kings', Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. With no fewer than

16 of the 33 Dutch songs in this collection to his name, Obrecht is the

central figure of this source. Many works are unica, appearing in no

other extant source. These compositions probably reached the Spanish

court by way of Ferrara, where Obrecht resided at the express request of

Ercole d'Este in 1487/88. The duke must have been one of his greatest

admirers, for he offered him the sought-after office there of maestro di cappella.

Obrecht would outlive his patron, who died in January 1505, by only a

few months. In July of that same year, he became one of the many victims

of the plague epidemic, the feared Black Death. After a somewhat

erratic career, Ferrara became his final resting place, far from home.

The presence of Obrecht (and of many other Franco-Flemish composers) in

Italy also explains the great number of Italian sources in which his

Dutch songs are found, including various Florentine manuscripts and the

first printed books of music which Ottaviano dei Petrucci published at

the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Somewhat problematic is

the fact that in many cases, only the first notes or the first line of

the song text has been supplied; the complete text is generally missing.

In some cases, the vocal version can be reconstructed on the basis of

concordant sources (e.g., Meiskin es u cutkin ru? and Rompeltier,

both on the basis of a Florentine collection of anonymous polyphonic

settings on an identical or closely related text). The text of the

sorrowful Weet ghij wat mijnder jongher herten deert can be

reconstructed with the help of the anonymous version (based on Obrecht's

tenor melody) in the Brussels-Tournai part-books. For the most part,

however, these seem to be instrumental versions of the original songs.

This was in fact a current practice, frequent indications of which can

be found in archival sources. At the court in Ferrara, for instance,

there were, besides Flemish and French singers, many Italian and German

instrumentalists, especially wind players. This created a unique

interchange between the vocal and instrumental traditions. In 1495, for

example, the Venetian trumpet player Giovanni Alvise wrote a letter to

Francesco Gonzaga, duke of Mantua, in which he mentions that he has

arranged works by Obrecht for five or six wind instruments. This was a

practice with which Obrecht himself, as the son of a Ghent city trumpet

player, would certainly have been acquainted. These musicians performed

not only vocal works instrumentally, but also improvised on existing

melodies which served as the basis of a composition in the form of a

cantus firmus. Obrecht, too, often took this compositional procedure as

his point of departure. A good illustration of this is the very popular Tandernaken al op den Rijn,

a song in which two girlfriends carry on a conversation which is

overheard by the admirer of one them. The Antwerp songbook is one of the

sources for the text and melody of this work. In his three-voice

version, Obrecht places the original (folksong-)melody in the tenor

voice as the other parts weave a lively contrapuntal texture around it.

The composer also makes use of a (generally unidentified) cantus firmus

in the textless works and in the Fuga. The cantus firmus is

notated in long notes in one of the parts or handled canonically. These

may be instrumentally reworked passages from mass compositions.

Some

songs and chansons are stylistically ahead of their time, showing early

characteristics of the Parisian chanson. They are often clever, fresh

and uncomplicated works characterised by a sparing use of imitative

counterpoint, as homophonic and declamatory passages are combined with a

simple harmonic language. Dialogues can develop between the different

parts, sometimes in paired voices. For instance, the superius and tenor

parts in Waer sij di Han? are answered by the altus and the bass with Wie roupt ons daer? In Meiskin es u catkin ru?

the altus and tenor voices carry on a sort of 'dialogue of fools'

between a man and a woman. The melody sometimes reflects the mood of the

text. In Weet ghij wat mijnder jongher herten deert, the

descending lines and low register of the superius mirror the lover's

lamenting, in contrast to the ascending melodic line to the highest note

on als een donderslach.

Obrecht's Dutch songs were no

doubt written while he was active in the Low Countries in Bergen op

Zoom, Bruges, Antwerp or Cambrai, cities where he worked as sanghmeestere

in the �churches. All these cities were vibrant places where there was a

buzz of activity and where urban and bourgeois music culture could

bloom to the full. Some of the songs may have been intended for refreinfeesten (orators' competitions), theatre performances, morality plays or song contests that were organised by the many rederijkerskamers

(orators' associations). The choristers at the church of St Donatian in

Bruges, at the time under Obrecht's predecessor Alianus De Groote, took

a very active part in such events. Als al de weerelt in vruechden leeft is probably based on an orator's poem. Other songs were probably intended as Spielmusik for city players.

Traditionally,

of course, French was the leading language for the secular polyphonic

repertoire. It should come then as no surprise to find Obrecht writing

in this tradition as well. He bases the four-voice Fors seulement l'attente que je meure

on Ockeghem's three-voice rondeau of the same name. Ockeghem's superius

part is used as a cantus firmus and the tenor melody appears in the

superius. Here again, the text is missing in the source, but it has been

possible to reconstruct a vocal version. Obrecht also followed the new

tendency of using popular folk melodies in chansons.

Finally,

this recording includes several sacred motets and liturgical

compositions. As in the majority of Obrecht's motet compositions, the

theme of the Virgin dominates. The function of these works can be

situated within the collegiate churches at which he was active and where

such Marian motets were performed daily in the Marian offices. The

cantus firmi of Ave maris stella and Beata es, Maria come from monophonic Latin chants for the Virgin. In the second section of Beata es, Maria, the text and melody of the sequence Ave Maria are added in the altus and tenor parts. For the Ave regina caelorum,

Obrecht has based his work on the motet of the same name by the English

composer Walter Frye. He quotes the tenor almost note for note, while

the superius part is based on the well-known Marian antiphon. The

attribution of the alternatim setting of the Magnificat is in some doubt, as the work differs stylistically from Obrecht's other work.

Translation: Stratton Bull