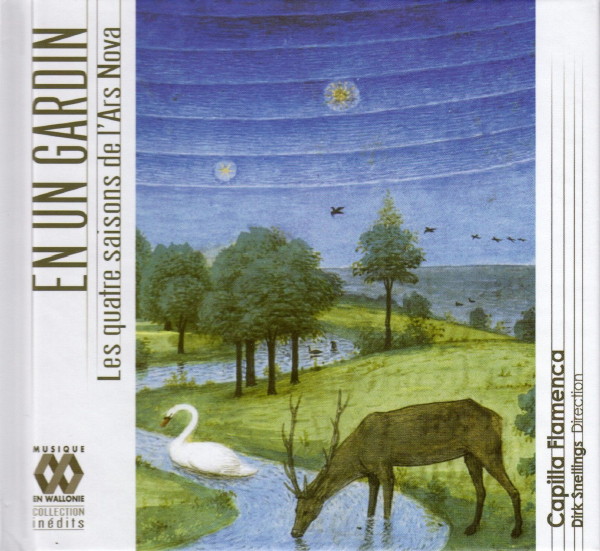

En un gardin. Les quatre saisons de l'Ars Nova

Capilla Flamenca / Manuscrits de Stavelot, Mons, Utrecht, Leiden

medieval.org

capilla.be

Musique en Wallonie 0852

2008

Bernard de CLUNY

1. Apollinis eclipsatur ~

Zodiacum signis ~

In omnem terram [3:05]

L'hiver

Thomas FABRI

2. Sinceram salutem care [6:40]

3. En discort [5:44]

anonymus | Faenza Codex

4. D'ardent desir ~

Nigra est ~

Se fus d'amer [2:52]

anonymus

5. Adieu vous di [4:13]

anonymus

Le printemps

6. Or t'am va [2:20]

anonymus

Martinus FABRI

7. Eer ende lof [1:48]

Philippe de VITRY

8. Vos, quid admiramini virginem ~

Gratissima virginis ~

Gaude gloriosa [2:16]

9. De plus souvent [1:10]

anonymus

Nicholas PYKINI

10. Playsance or tost [1:27]

L'été

Jean VAILLANT

11. Par maintes foys [3:05]

Johannes VINDERHOUT (?)

12. Comes Flandriae ~

Rector creatorum ~

In cimbalis [2:13]

13. Je suys toujours [3:32]

anonymus

14. Cheulz qui volent [2:42]

anonymus

L'automne

15. En un gardin [3:44]

anonymus

Philippe de VITRY

16. Adesto sancta trinitas ~

Firmissime fidem ~

Alleluia Benedicta [2:45]

Guillaume de MACHAUT

17. Se vous n'estes [4:08]

anonymus

18. Ist my bescheert [4:16]

anonymus

CAPILLA FLAMENCA

Dirk Snellings

Marnix De Cat, countertenor

Tore Denys, tenor

Lieven Termont, baritone

Dirk Snellings, bass

Jan Van Outryve, lute

Liam Fennelly, fiddle

Patrick Denecker, recorders

Artistic concept, Dirk Snellings

Légendes des illustrations :

Adam et Eve au Paradis (détail), Livre des sept âges du monde, Mons, miniature de Simon Marmion, ca 1455, Bruxelles, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Ms. 9047, f. 1v.

Notice :

1. La Capilla Flamenca, © Miel Pieters.

2. Firmissime fidem teneamus, détail du Rotulus de Stavelot, 1335, Bruxelles, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Ms. 19606.

3. Rotulus de Stavelot (miniature du frontispice), 1335, Bruxelles, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Ms. 19606.

4. Construction de l'abbaye de Stavelot, détail du Retable disparu de saint Remade de Stavelot, 1666, dessin, Liège, Archives de l'État.

5. En un gardin, Utrecht, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, Ms. 1846 (6E37 Il), f.21v. Cheulz qui volent, Leiden, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, Ms. BPL 2720, f.6r.

6. Cheulz qui volent, Leiden, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, Ms. BPL 2720, f.6r. Remerciements :

Nous remercions

·

Madame Nadine Henrard (Université de Liège) pour la restauration et la

traduction des textes en ancien français des plages 3, 11, 13, 14, 15,

17, et

· Madame Agathe Sultan (Université Michel de Montaigne - Bordeaux 3) pour les plages 4, 5, 10 ;

·

Monsieur Frank Willaert et Madame Colette Van Coolput-Storms

(Universiteit Antwerpen) pour la traduction des textes en ancien

néerlandais plages 7 et 18 ;

· Monsieur Arthur Bodson (recteur

honoraire de l'Université de Liège) pour la traduction des textes latins

des plages 2, 8, 16 et pour son aide précieuse à la compréhension des

autres textes latins, ainsi que

· Madame Anne-Emmanuelle Ceulemans (Université catholique

de Louvain) pour la traduction française de la notice.

Remerciements à Monsieur Alain Goossens et à la Bibliothèque royale de Belgique.

Production : Musique en Wallonie, Belgique (http://www.musiqueenwallonie.be)

Enregistrement : 25-29 février 2008, Chapelle Saint-Camille, Bierbeek

Prise de son et montage : Jo Cops Productions

Directeur de projet : Christophe Pirenne

Graphisme : Valérian Larose

La Capilla Flamenca bénéficie du soutien des autorités flamandes

Réalisé

avec le concours du Ministère de la Communauté française de Belgique

Direction générale de la culture - Service de la musique

© 2009

English liner notes

EN UN GARDIN

Les quatre saisons de l'Ars Nova

De Nederlanden

speelden in de vijftiende en zestiende eeuw onmiskenbaar een essentiële

rol in de ontwikkeling van de meerstemmige muziek van West-Europa. Zij

waren één van de dichtst bewoonde regio's van die tijd met

verstedelijkte gebieden die gunstig gelegen waren langs verschillende

handelsroutes en die vooral dankzij de lakenproductie rijk werden. Door

financiële inspanningen van de rijke burgerij hadden deze steden zich

tot interessante centra kunnen ontwikkelen waar de muziekcultuur kon

groeien en bloeien. De politiek van de Bourgondische hertogen voerde

kunst en cultuur bovendien hoog in het vaandel: diverse stichtingen die

zij oprichtten vormden een voorbeeld voor de burgerij en lagere adel die

wat graag probeerden het hof te imiteren en zo soortgelijke, zij het

vaak minder ambitieuze, fundaties gingen financieren. Het onafhankelijke

prinsbisdom Luik trok in deze eenzelfde kaart.

Het fundament van

de muzikale bloei in de vijftiende en zestiende eeuw werd echter

duidelijk al in de veertiende eeuw gelegd. De invloed van de Franse Ars Nova

(de term, een verzamelbegrip werd onder meer lange tijd aan de Franse

componist, bisschop en theoreticus Philippe de Vitry die het gebruikt

zou hebben in zijn gelijknamige traktaat van ca. 1322, hierbij

verwijzend naar een "nieuwe" muziektaal die werd ontwikkeld vanaf de

eerste decennia van de veertiende eeuw) en de daaruit voortkomende Ars Subtilior (verwijzend naar een nog meer 'gemaniëreerde' compositiestijl) kan hierbij zeker niet ontkend worden.

Helaas

zijn uit deze "waanzinnig boeiende" veertiende eeuw in de Nederlanden

vrijwel geen volledige handschriften bewaard - in tegenstelling tot

Frankrijk, waar men schitterend verluchte handschriften bezit - en moet

je als musicus gedeeltelijk als archeoloog te werk gaan. Wat ons hier

rest zijn in hoofdzaak fragmenten die vooral in de loop van de

twintigste eeuw, vaak gerecupereerd uit boekbanden, aan de oppervlakte

kwamen. Hoewel ze zeer disparaat en vaak ook zeer onvolledig zijn, tonen

deze fragmenten aan dat de Ars Nova in de Nederlanden toch ook eigen

accenten wist te leggen (net als in Engeland en Italië), en daarom door

Reinhard Strohm voor de latere periode de Lateral tradition

genoemd wordt. Zo werd dit muzikaal (zw)erfgoed door lokale musici

verder uitgewerkt, ontstonden er vaak varianten, voornamelijk van de

bovenstem, werd er al eens een nieuwe stem toegevoegd aan een

driestemmig werk en zette men ook Nederlandse teksten op muziek,

weliswaar met behoud van (Franse) literair/muzikale vormschema's als ballade, virelai en rondeau.

Uit

vaak onvolledige en bovendien nog niet volledig bestudeerde rekeningen

en inventarissen weten we dat er een vrij aanzienlijke muziekproductie

moet zijn geweest. Zo bezat het kapittel van Sint-Donaas te Brugge in

1274 reeds 136 boeken en verwierf men tussen 1354 en 1402 nog heel wat

meer (eenstemmige) muziekboeken. In 1377 schafte men zich een liber motettorum

aan en vanaf die periode worden geleidelijk aan ook knapenstemmen

ingeschakeld in het meerstemmige repertoire dat lange tijd voorbehouden

was voor mannenstemmen. Ook in het relatief kleine Tongeren, gelegen in

het prinsbisdom Luik, is in 1394 sprake van een motetboek en in 1399 van

een orgelboek waarin wellicht kunstig versierde orgelstukken stonden.

Deze voorbeelden illustreren slechts het topje van de ijsberg.

Terzijde

nog een merkwaardigheid: vooral buitenlandse complete bronnen tonen

onmiskenbaar aan dat wereldlijke en geestelijke muziek niet altijd werd

gescheiden en dat de uitvoerders van kerkmuziek evenzeer

verantwoordelijk waren voor de uitvoering van de profane muziek.

Kerkboeken mochten in principe het kerkgebouw niet verlaten, maar dat lag wellicht anders voor rotuli.

Deze aan elkaar genaaide, langwerpige perkamenten "muziekrollen" konden

door hun fysieke toestand al gemakkelijker worden meegenomen -

overigens net zoals een katern van een handschrift vooraleer deze

laatste werd ingebonden in een codex.

Een bijzonder fraai exemplaar van zo een rotulus,

weliswaar niet als reizend object geconcipieerd wordt momenteel bewaard

in de Brusselse Koninklijke Bibliotheek (ms. 19606). Het bevat naast

één conductus, 9 motetten, waarvan één een unicum is. De tekst bevat

duidelijk Waalse elementen hetgeen de herkomst uit Malmedy (cf. infra)

bevestigt. Het handschrift kwam er terecht via de verzamelaar, notaris,

dichter, collectioneur van Vlaamse volksliederen, historicus Jan Frans

Willems. Gelet op de iconografie (o.a. een Duitse adelaar) is dit

vrijwel ongehavende exemplaar meer dan waarschijnlijk afkomstig uit de

Benedictijner dubbelabdij van Malmedy/Stavelot, gesticht in 648/650 door

de heilige Remaclus. Recent onderzoek van Karl Kügle heeft aangetoond

dat deze rotulus ontstond in 1335 n.a.v. de aanstelling van een nieuwe

abt van de genoemde prinselijke en keizerlijke dubbelabdij. Na het

rampzalige abbatiaat (1307 - 1324) van Henricus de Bolan, aangesteld op

voorspraak van (le Duitse keizer Hendrik VII van Luxemburg, probeerde

men wellicht via acht motetten uit de Roman de Fauvel de

monnikengemeenschap en de buitenwereld te overtuigen van een beter

toekomstig bestuur. Vier van deze motetten hekelen slecht bestuur, vier

andere motetten daarentegen zijn religieus en hoopvol. Het Firmissime fidem / Adesto sancta frinitas / Alleluia Benedicta

van Philippe de Vitry is een voorbeeld van zo'n 'positief' motet.

Mogelijk ook omwille van de Alleluia-tekst past hot motet ook liturgisch

gezien in de paastijd van 1335, periode waarin de nieuwe abt, Winricus

de Pomeria - zij het niet onverdeeld werd gekozen. Pikant detail is dat

het nog niet geïdentificeerde dier in de openingsminiatuur wellicht een

draak is, die verwijst naar de etymologische betekenis van Malmedy (a malo mundatum:

gereinigd/gezuiverd van het kwade) en dat de twee adelaars symbool

staan voor de Duitse keizer enerzijds en de prinselijke status van de

abt anderzijds. Dat men de muziek op een rotulus noteerde heeft

hier geen praktische betekenis maar een symbolische. Men wou via deze

verschijningsvorm het ceremoniële aspect in de verf zetten.

Zulke

motetten, zowel voor geestelijk als wereldlijk gebruik, zijn in deze

periode vaak nog polytekstueel en bevatten dus meerdere teksten die

eventueel eerder successief dan wel simultaan werden gezongen. Heel

waarschijnlijk waren de toehoorders/uitvoerders erg vertrouwd met deze

vaak ingewikkelde teksten, want de tekstverstaanbaarheid wordt

natuurlijk in belangrijke mate bemoeilijkt door het gelijktijdig zingen

van verschillende teksten, vaak nog in verschillende talen. De onderstem

is meestal het vertrekpunt voor de componist. Daarbij neemt hij een

bestaande geestelijke of wereldlijke melodie (color) als basis en structureert hij deze volgens een ritmisch patroon (talea). Samen vormen color en talea

de zogenaamde "isoritmie" - een "moderne" terminologie uit 1904 - en

spreken we bijgevolg van isoritmische motetten. Die melodische en

ritmische patronen vallen in de meeste gevallen niet samen, hetgeen de

herkenbaarheid van de bestaande melodie nog bemoeilijkt. We hebben dus

te maken met een erg gecodeerde muziektaal die in wezen wel

gelijkenissen vertoont met de essentie van de gotiek: een stevige

onderbouw (in langere notenwaarden) waarboven meer spitse (lees

beweeglijke) constructies worden gebouwd.

Rotuli zijn eerder schaars. In Tongeren bewaart men twee fragmenten van rotuli die als boekband werden gebruikt. Naast Guillaume De Machaut's Rondeau Se vous n'estes

(een erg verbreid werk, onder meer ook opgenomen in de Gentse

fragmenten afkomstig als schutblad van een renteboek van de abdij van

Groenenbriel) en het eveneens goed verspreidde anonieme Esperance qui en mon coeur,

bevatten deze twee gehavende stroken niet minder dan negen anonieme

(meestal onvolledige) unica, waaronder het instrumentaal uitgevoerde

virelai De plus souvent.

Typerend voor de late veertiende

eeuw zijn verder de vogelroepenvirelai's. Ogenschijnlijk betreft het

lief elijke bostaferelen waarbij de dichter/componist verschillende

vogels imiteert, maar ook hier is weer een dubbele bodem aanwezig. De

hier opgenomen vogelroepen-imitatie Par maintes foys geeft niets

anders weer dan een symbolisch steekspel tussen de nachtegaal met zijn

zoete liefdesliederen en de neststalende koekoek wiens opdringerig cucu

niet accordeert met de gezangen van de nachtegaal. Deze laatste roept

dan ook andere vogels, zoals de leeuwerik en de goudvink, op om de

koekoek te doden (oci, oci). De foliant waarop onder meer deze

versie van het lied van de Parijzenaar Jean Vaillant werd genoteerd,

evenwel met een interessante alternatieve bovenstem, werd in latere

tijden in niet minder dan drie deeltjes versneden. Als bij toeval kwamen

ze op het einde van de 20ste eeuw weer samen, toen een Naamse

verzamelaar het ontbrekende deeltje bij een Londense antiquair kon

kopen.

Op de achterzijde van deze versneden foliant staat het vrolijke meilied Playsance or tost,

een virelai van Nicholas Pykini. Hierin wordt opgeroepen tot plezier

maken bij het horen van de speelse tonen van de nachtegaal en de

papegaai, mogelijk een verwijzing naar het pauselijke hof in Avignon

(met de 'pape gay') of nog waarschijnlijker naar de papegaai als symbool

van Wenceslas I van Brabant/Luxemburg in wiens dienst Pykini stond.

Bijzonder

interessant in verband met de verspreiding van de liedcultuur in de

Nederlanden zijn de Leidse fragmenten. Ze geven aan dat een

linguïstische grens moeilijk te trekken is en ten dele ook zinloos zou

zijn. De zes bifolio's met muziek uit de Ars Subtilior zijn

wellicht in relatie te brengen met het Beiers-Hollands-Henegouwse hof in

Den Haag. Door een dubbelhuwelijk van de zoon en dochter van Philips de

Stoute en de dochter en zoon van Albert van Holland, Zeeland en

Henegouwen ontstonden interessante nieuwe culturele contacten. Ofschoon

dit gehavende chansonnierfragment rondeaus en virelais in de

gebruikelijke, meer verfijnde Ars Nova- en Ars Subtiliorstill bevat, springen twee vrolijke liederen (Cheulz qui volent en Eer ende lof)

eruit door hun eenvoudige, homofone, haast declamatorische stijl. In

tegenstelling tot wat we gewend zijn op het vlak van de wereldlijke

muziek, meestal geconcipieerd voor een beweeglijke bovenstem en twee

minder beweeglijke, veeleer begeleidende onderstemmen, ontbreken de

melismen hier haast volledig. De aanwezigheid van liederen op

Nederlandse tekst geeft ook aan dat de noordelijke "Ars Nova lateralis",

zoals hierboven al aangehaald, een eigen gelaat krijgt en componisten

geleidelijk aan ook Nederlandse teksten op muziek gaan zetten.

Nog

vroeger vinden we in de Nederlanden ook Waalse elementen terug in de

zogenaamde codex Turijn (zo genoemd omwille van de bewaarplaats),

afkomstig uit de Benedictijnerabdij van Saint-Jacques in Luik.

Het lied Ist mi bescheert,

een anonieme ballade, is dan weer terug te vinden in de zogenaamde

Utrechtse fragmenten (Ms. 1846/2). Mogelijk is het handschrift afkomstig

uit de regio van Landen (België), omdat er sprake is van de componist

clericus de Landis. Deze specifieke herkomst is echter niet met

zekerheid te bepalen, evenmin als deze van de andere Utrechtse

fragmenten (Ms. 1846/1), die door sommigen eerder in Brugge worden

gesitueerd. Gelet op het aantal concordanties - zo komt het werk voor in

de codex Chantilly, in de Reina-codex alsook in het handschrift van

Straatsburg (in een later afschrift nu bewaard in de

conservatoriumbibliotheek van Brussel) - moeten we eerder spreken van

een Europees repertoire met vaak regionale accenten.

En un gardin

is een unicum in deze bron. Opnieuw is de dichter / componist in

vervoering van de vogelgeluiden en is het vooral de wijze arend in de

tuin die zijn aandacht trekt. Deze vogel wordt aanzien als de meest

wijze aangezien hij het hoogst kan vliegen en dus het dichtst bij het

opperwezen komt. In En discort geraken verlangen en hoop het niet

eens in het hart van de dichter en als Fortuna - zo bepalend voor het

middeleeuwse denken - haar best niet doet, lijkt de dood de meest

aangewezen weg... Bij deze uitvoering wordt dankbaar gebruik gemaakt van

een versierde versie uit de codex Faenza, zowat het meest

toonaangevende orgelhandschrift uit deze periode.

Twee werken,

hier terug te vinden, hebben een link met Brugge, de stad waar de

Bourgondische hofkapel regelmatig verbleef. De rol van deze reizende

hofkapel die vooral de Lage Landen, maar soms ook wel belangrijke

Europese steden bezocht, kan niet worden onderschat als doorgeefluik van

muzikale stijlen. Er is ten eerste Thomas Fabri, zangmeester van

Sint-Donaas in Brugge, die een bijzondere puzzelcanon Sinceram salutem care

schreef, die je op meerdere manieren kan zingen. De tekst bevat een

boodschap voor een collega musicus, die uitgenodigd wordt te

"solmiseren". De auteur wil zijn collega wel ontmoeten in Brugge om bij

een geopende fles (Bachum lacerare) ut-re-mi-fa-so-la te zingen.

De naam van de collega is Buclarus, die een zeereis plant, terwijl hij

eigenlijk verder muziekles zou moeten geven. De tekst 0 ros Bachi me

rorare, geciteerd in de tweede strofe die hier omwille van de lengte

niet wordt gezongen, is een allusie op de introitus voor de advent: Rorate celi desuper.

Bacchus invloed is blijkbaar zo groot dat ze niet verder komen dan een

eenvoudig rijm op "a-re" (verwijzend ook naar het einde van het

hexachord "la-re").

Een Magister Egardus (mogelijk te vereenzelvigen met de Brugse succentor Johannes Ecghaerd) schreef een soortelijk werk (Furnos reliquisti quare?) waarin er sprake is dat frater Buclarus Furnos (i.e. de harten of de stad Veurne) heeft verlaten...

Het staatsmotet én het muzikantenmotet Comes Flandriae / Rector creatorum / In cimbalis

is gecomponeerd voor Sint-Donaas in Brugge. Het looft de overwinning

van de Fransgezinde graaf Lodewijk van Male in 1381/1382. Dit alles

wordt op symbolische wijze ondersteund door het geluid van cimbalen

(verwijzend naar Boëthius) in de tenorstem. De tekst van de triplum

legt de nadruk op de kracht van de muziek ten overstaan van de macht

van de heersers. De tekst van de motetus spreekt over God die vereerd

wordt door een koor engelen, in dit geval van musici. Het "zangersmotet"

Apolonis eclipsatur / Zodiacum signis / In omnem terram van

Bernard de Cluny is een wijd verspreid werk (vb. ook in het handschrift

Straatsburg/Brussel terug te vinden), waarin de lof wordt gezongen van

zowel vroegere musici (Pythagoras, Boëthius), als eigentijdse (Vitry,

Johannes De Muris). Het is een schitterende lofbetuiging op de kracht

van de muziek. Merkwaardig genoeg is het ingewikkelde werk ook

overgeleverd in een eenvoudige tweestemmige klavierzetting, waarin enkel

motetus en tenor zijn behouden. Het toont opnieuw aan hoe gevarieerd de

verschijningsvorm van deze composities kan zijn.

In al hun

gevarieerdheid en kwaliteit tonen de werken op deze cd aan dat de muziek

in de Lage Landen, historisch gezien zich uitstrekkend van

Noord-Holland via het Land van Luik tot het huidige Noord-Frankrijk,

alles in haar mars heeft om een muzikale boom van formaat klaar te

stomen. De componisten en uitvoerders uit deze regio's zullen vanaf nu,

onder meer dankzij de vele fundaties in de grootste kerken en de

training in de koralenscholen, ervoor zorgen dat de Lage landen aan de

Noordzee klaar zijn om de muzikale graanschuur van Europa te worden.

Hierbij wordt gebouwd aan de weg van de Europese polyfonie, die onder

meer in de muziek van Johann Sebastian Bach een absoluut hoogtepunt zal

vinden.

Eugeen Schreurs

Resonant, Centrum voor Vlaams Muzikaal Erfgoed

EN UN GARDIN

Les quatre saisons de l'Ars Nova

There

is no doubt that in the 15th and 16th centuries the erstwhile Low

Countries played a crucial role in the development of western European

polyphonic music. This was one of the most densely populated regions of

Europe, with urbanised areas that were favourably situated on commercial

routes, its wealth deriving principally from the manufacture of cloth.

Thanks to the financial contribution of the rich bourgeoisie, these

towns developed into lively centres where a musical culture was able to

burgeon and flourish. Furthermore, it was the policy of the Dukes of

Burgundy to give priority to the arts and other cultural matters. The

various institutions founded by them served as examples to the

bourgeoisie and the minor aristocracy, who enjoyed imitating court life

and set about financing similar foundations, although on a smaller

scale. The independent principality of Liège was a case in point.

It

was, however, in the 14th century that the musical flowering of the

15th and 16th centuries clearly originated. The influence of the French Ars Nova

(a generic term long attributed to the French composer, bishop and

music theorist Philippe de Vitry, who is thought to have used it in a

treatise of that name written c.1332 and referring to the “innovative”

musical language that developed during the first decades of the 14th

century) and of the Ars Subtilior (which goes back to an even more mannered style) that succeeded it, is undeniable.

In

France some magnificently illuminated musical manuscripts have been

preserved, offering a wealth of testimony to the extraordinary 14th

century, but in the former Low Countries hardly a single complete

manuscript has come down to us. Musicologists therefore have to become

archaeologists. Most of the fragments recorded in this CD were unearthed

during the 20th century, often salvaged from book bindings. Despite

their disparities and their often incomplete state, they show how, just

as in England and Italy, the Ars Nova in the Low Countries had

its own distinct physiognomy. These different strands have been

described by Reinhard Strohm as “lateral traditions”. They encompass a

musical heritage developed by local composers and subject to numerous

variants, particularly in the uppermost voice. Sometimes an extra voice

was added to works originally for three voices, and certain pieces were

provided with texts in Dutch, though they preserved the verse forms

inherited from French poetry and music, such as the ballade, virelai and

rondeau.

Incomplete sets of accounts and inventories, most of

which have not been the subject of detailed research, show that the

amount of music produced must have been considerable. In 1274, for

example, the chapter of St Donatien in Bruges already possessed 136

books of monodic music, and it amassed many more between 1354 and 1402.

In 1377 it acquired a liber motettorum, and from that date choirs

of children's voices were progressively incorporated into the

polyphonic repertoire, which had long been the exclusive preserve of

male voices. Even the modest little town of Tongres, situated within the

principality of Liège, had a book of motets in 1394, and by 1399 it

possessed an organ book which must have included pieces with erudite

ornamentation that were specifically intended for the organ. These

examples represent only the tip of a vast iceberg. Another interesting

point is that the complete sources found more especially in other

countries irrefutably prove that there was no clear distinction between

secular and sacred music, and that the executants of church music were

in charge of performances of secular music too.

Books belonging to churches could not in principle be taken out of the building, but it was clearly another matter for the rotuli.

These were rolls of music made up of long pieces of parchment sewn

together, and their smaller format, similar to the as yet unbound

volumes in codices, made them more portable. A splendid example of a rotulus,

albeit one not actually intended to be carried around, is now preserved

in the royal library at Brussels (Ms. 19606). In addition to a conductus it consists of nine motets including an unicum.

The text contains elements that are clearly Walloon, which confirms

that it originated in Malmédy (see below). The manuscript was acquired

thanks to Jan Frans Willems, a collector, notary, poet, historian and

compiler of a collection of Flemish popular songs. Because of its

iconography (notably a Germanic eagle) it may be assumed that this

almost intact work originated in the Benedictine abbey at

Malmédy-Stavelot (near Liège), which was founded in 648-650 by St

Remade. Recent research by Karl Kuegle has demonstrated that this rotulus

was completed in 1335 following the installation of a new abbot in the

abbey, which was both princely and imperial. After the disastrous reign

of the abbot Henricus de Bolan (1307-1324), who had been appointed on

the recommendation of the German emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg, the

attempt was no doubt made, with the help of the eight motets in the

Roman de Fauvel, to convince the monastic community and the outside

world that they would be better governed in future. Four of these motets

denounce bad management while four others are religious and optimistic.

Firmissime fidem / Adesto sancto trinitas / Alleluia Benedicta

by Philippe de Vitry is an example of this kind of “positive” motet.

From a liturgical viewpoint the presence of the Alleluia may suggest

that the motet was intended for Eastertide 1335, when a new abbot,

Winricus of Pomerania, was elected, though not unopposed. An amusing

detail is that the hitherto unidentified animal in the miniature at the

front is definitely a dragon, which refers back to the etymological

meaning of “Malmédy” (a malo mundatum: purified of evil), and

that the two eagles symbolize the German emperor on the one hand and the

princely status of the abbot on the other. The fact that the music was

written on a rotulus has symbolical but not practical significance. The

object of this format was to promote the music's ceremonial character.

During

this period motets of this kind, intended for both religious and

secular use, were often still polytextual and therefore contained

several texts which were probably sung in succession rather than

simultaneously. Audiences and performers alike must have been familiar

with these texts, which were often made more complicated because their

intelligibility must have been compromised by the simultaneous singing

and the frequent use of different languages. The composer usually

centred his music on the lowest voice, consisting of a pre-existing

sacred or secular melody called a color. This was structured on a

rhythmic outline called a talea. The combination of a color and a talea

gave rise to a phenomenon which has been called isorhythm. a modern term

coined in 1904. For this reason we now speak of isorhythmic motets. The

melodic and rhythmic patterns are not generally synchronized, which

makes recognition of the pre-existing melody all the more difficult. We

are thus presented with a strongly codified musical language which

exhibits certain similarities with the gothic style of architecture: a

solid foundation (in long values) supporting more airy (i.e. mobile)

structures.

Rotuli are relatively rare. At Tongres two

fragments of rotuli have survived because they had been re-used in a

book binding. These two very damaged pieces of parchment contain the rondeau Se vous n'estes

by Guillaume de Machaut (a widely-known work, taken up again, for

instance, in the Ghent fragments, which survive on the flyleaf of an

account book at the abbey of Groenenbriel) and another well-known piece,

Esperance qui en mon coeur, plus nine anonymous individual

pieces, most of them incomplete, including the virelai De plus souvent.

This latter is given in this production in an instrumental

interpretation.

A few fragments come without doubt from the

collegiate church of Sainte Gudule in Brussels and contain an

isorhythmic motet also from the pen of Philippe de Vitry, Vos quid admiramini virginem / Gratissima virginis species / Gaude gloriosa.

Three different texts sing the praises of virgins in general and the

Virgin Mary in particular. The composer achieves a masterly combination

of the secular love-lyric and the type of religious poetry that

celebrates the mystic spiritual union.

Another typical composition of the late 14th century is the virelai

featuring bird calls. These appear to be charming sylvan tableaux in

which the poet and composer imitate various birds, but here again, a

twofold interpretation is possible. The birdsong imitations found in Par maintes foys

in this recording are in fact a symbolical clash between the

nightingale, with its sweetly amorous songs, and the cuckoo, infamous

for robbing nests, whose penetrating call jars with the nightingale's

lyricism. The nightingale appeals to other birds such as the lark and

bullfinch to kill the cuckoo (oci, oci). This song, composed by the Parisian Jean Vaillant and with a further upper voice ad libitum,

figures in a folio which was later cut up into three parts. These were

reunited at the end of the 20th century by chance when a collector from

Namur had the opportunity to buy the missing fragment from an

antiquarian dealer in London.

On the verso of this reconstituted folio there is another piece, the joyful May song Playsance or tost, a virelai

by Nicholas Pykini. The composer invites his listeners to enjoy

listening to the merry calls of the nightingale and the parrot. The play

on words “pape gay” may possibly constitute an allusion to the papal

court at Avignon; on the other hand, it is more likely that the parrot

symbolises Wenceslas I of Brabant and Luxembourg, since Pykini was

employed in his service.

As

regards the spread of the popularity of song in the Low Countries, the

most interesting are the fragments from Leiden. These show that it is

both difficult and to some extent futile to attempt to determine a

linguistic frontier. It is clear that the six polyphonic bifolios of the

Ars Subtilior should be seen in relation to the court at The Hague,

which was Bavarian, Dutch and Flemish. New cultural contacts had been

created through the double marriage of the son and daughter of Philip

the Bold with the daughter and son of Albert of Holland, Zeeland and

Hainault. Although this badly damaged fragment of a song-book contains

rondeaux and virelais in the usual refined style of the Ars Nova

and the Ars Subtilior, it also contains two joyful songs

(Cheulz qui volent and Eer ende lof)

which are distinguished by their simple, homophonic and almost

declamatory style. Usually the secular music of the period is intended

for a very mobile upper voice and two more static lower voices mainly

functioning as accompaniment; here, however, there are virtually no

melismas. As suggested above, the presence of songs with Dutch texts

lends the northern Ars Nova lateralis a distinctive character and shows

that these composers were beginning to write works in their own

language.

Earlier still, in the Low Countries, Walloon elements

are encountered in the so-called Turin codex (named after the city where

it is preserved), which in fact originated at the Benedictine abbey of

St Jacques at Liège.

The song Ist mi bescheert, an

anonymous ballade, is preserved in what are known as the Utrecht

fragments (Ms 1846/2). This manuscript may originate from the Landen

region in Belgium, because it is possibly by a composer known as

clericus de Landis; this attribution, however, remains open to doubt,

like that of the other Utrecht fragments (Ms 1846/1), thought by some to

be more probably from Bruges. Because this work reappears elsewhere, in

the Chantilly and Reina codices and the Strasbourg manuscript (of which

a later copy is kept in the Brussels Conservatoire), the most

satisfactory theory is that we are here dealing with a European

repertoire often coloured by regional influences.

En un gardin

is the only work of its kind in this source. Again the poet-composer

allows himself to be carried away by bird calls, and in this case it is

the eagle in the garden that attracts his attention. This bird is

considered the wisest because it can fly the highest and thus comes

closest to the Supreme Being. In En discort, desire and hope are

not in harmony in the poet's heart, and if Fortuna, who plays such a

crucial role in mediaeval thought. declines to intervene, death seems

the most obvious way forward. The performance here is based on an

illuminated version of the Faenza codex, the most important organ

manuscript of the period.

Two works have a link with the city of

Bruges, where the musical establishment of the court of Burgundy

regularly stayed. As regards the dissemination of musical styles it is

hardly possible to overestimate the importance of this itinerant band of

court musicians, which resided mainly in the Low Countries but also

visited various important cities elsewhere in Europe. The first work is a

remarkable, enigmatic canon, Sinceram salutem care, composed by

the choirmaster at St Donatien in Bruges and capable of being performed

in different ways. The text contains a message for a musician colleague,

who is invited to sing it to sol-fa. The composer wishes to meet this

colleague in Bruges to sing ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la around a good bottle of wine

(Bachum lacerare). The colleague's name is Buclarus: he is preparing to leave

on a sea voyage while supposedly giving music lessons.

The phrase O ros bachi me rorare, occurring in the second verse

(not sung here, owing to its great length) alludes to the Advent introit,

Rorate celi desuper.

The influence of Bacchus is apparently so great that they get no

further than a simple rhyme on “a-re”, a reference to part of the

hexachord (“la-re”).

A certain Magister Egardus (whom we can

perhaps identify as the succentor of Bruges, Johannes Ecghaerd) wrote a

similar work, Fumos reliquisti quare?, which centres on the fact that

Brother Buclarus had left Fumos (i.e. the hearts or the city of Veurne

in Flanders).

Comes Flandriae / Rector creatorum / In cimbalis,

a motet in praise of the state and of musicians, was composed for St

Donatien in Bruges. It celebrates the victory of the francophile Count

Louis de Male in 1381-82 and is symbolically underpinned by a sound as

of cymbals in the tenor voice (a reference to Boethius). The triplum's

text emphasizes the power of music compared to the might of sovereigns.

The duplum's text speaks of God being worshipped by a choir of angels in

the guise of musicians. The “motet de chanteurs” Apolonis eclipsatur / Zodiacum signis / In omnem terram

by Bernard de Cluny is known over a wide area (it is found, for

instance, in the Strasbourg-Brussels manuscript). It sings the praises

of the musicians of the past (Pythagoras and Boethius) and of the

present (Vitry and Jean des Murs) and forms an impressive paean in

praise of the power of music. It is interesting to note that this

complex work has come down to us in a two-voice keyboard version,

retaining only the duplum and tenor lines. This shows once again how

widely the presentation of these works can vary.

Thanks to their

immense diversity and their many qualities, the works in this CD show

that at the end of the 14th century the music of the Low Countries,

which historically extended from the north of Holland across the

province of Liège to what is now northern France, contains the germ of

all the elements that were to form the basis of the 15th century's

remarkable musical flowering. The numerous foundations in the principal

churches and the formation of choir schools enabled composers and

performers to make the Low Countries along the North Sea coast into a

fertile source of musicians for the whole of Europe. The path to

European polyphony was thrown open, leading ultimately to its supreme

manifestation in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Eugeen Schreurs

Resonant, Centre of Flemish Musical Heritage

Translation: Celia Skrine