PIERRE DE LA RUE

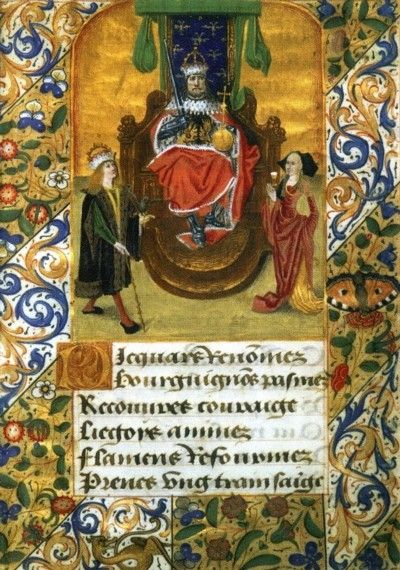

One of the most significant and prolific composers of his generation,

Pierre de la Rue was almost certainly born in Tournai, a city ruled by

France in the fifteenth century - and chief town of the current Belgian

province of Hainaut. His birth-date and education are unknown, but the

latter is very likely to have been in the maîtrise of the city's

important cathedral. As with so many composers of the time, we know

little of his early employment (since La Rue sang the highest vocal

part, he is unlikely to be the tenorist Peter vander Straten, as

formerly thought). In his early years he probably worked at the church

of Sint Odenrode in the town of the same name (in the current Dutch

Brabant, near 's-Hertogenbosch), but by 1492 he was employed in the

chapel of Maximilian, the future Holy Roman Emperor, widower of Mary of

Burgundy, and father of Philip the Fair and Margaret of Austria, each

of whom would eventually include La Rue among their musicians

[Illustration 1].

The Habsburg-Burgundian court was a key political player on the world

stage, and it was equally important as a major musical center as well,

with a very large collection of permanent chapel members who performed

an impressive daily series of musical services for its ruler: a daily

polyphonic mass and daily Vespers and Compline services, both of which

incorporated polyphony as well. On major feast days, and during Advent

and Lent, this round of musical activities was expanded still further.

La Rue thus had a ready outlet for his compositions, which grew to

include almost forty masses and individual mass movements, almost two

dozen motets, a complete series of eight Magnificats, and, for

non-liturgical entertainment, more than forty secular works. He also

had an impressive côterie of colleagues in the court chapel,

including such luminaries as Gaspar van Weerbeke, Alexander Agricola,

Nicolas Champion, Marbrianus de Orto, and Antonius Divitis. Yet La Rue

outshone them all in the quantity, quality, and variety of pieces he

wrote for the court. His compositions were the foundation as well for

another by-product of courtly splendor: a series of more than sixty

music manuscripts, some richly illuminated, that were generated by

scribes connected with the court and then given to royal patrons and

wealthy individuals across Europe. These manuscripts contain almost all

of La Rue's compositions.

By necessity, the court was a peripatetic one: rulers needed to show

their face to their subjects, and musical ceremony was a necessity for

the trappings of power. Habsburg-Burgundy was an especially wide-flung

realm, a good portion of which La Rue visited over the years of his

service. Under Maximilian he saw much of German-speaking lands; when

Philip the Fair came of age the court chapel returned to the Low

Countries and constantly moved about there. By 1501 Philip's wife Juana

was heiress to her homeland of Castile, and the court made an extended

trip to see what were to be her (or rather Philip's) future domains,

crossing through France, residing for months in Spain, and returning

slowly back through Habsburg territory.

In 1504 Isabella of Castile died, and in early 1506 Philip and his

massive retinue departed for Spain to lay claim to Castile. This time

they went by sea, but terrible storms forced them to land in England

and remain for months as guests of Henry VII. Less than half a year

after finally reaching Spain, Philip died, plunging the court into

confusion. La Rue and numerous chapel members remained in Spain,

serving Juana in her incessant mourning for her lost husband, and only

returning north in 1508.

On Philip's death, the new ruler of Habsburg-Burgundy was, in theory,

his six-year-old son, the archduke Charles. In practice, Charles's aunt

(and Philip's sister) Margaret of Austria governed the Low Countries

until Charles was declared of age in 1514. During this time the court

was, for the most part, resident in either Malines or Brussels, a

period of stability that seems to have facilitated La Rue's

compositional work. Then from 1514 to 1516 the court was on the move

again, as Charles toured the territories now under his direct rule. It

is likely that his plans for a trip to Spain, of which he became King

after the death of Ferdinand of Aragon, prompted La Rue's decision to

retire to Courtrai, where he owned a prebend, in 1516. He lived there

until his death on 20 November 1518.

The works recorded here form a rich sampling of his output from

different times in his career, many Marian in theme: four masses, five

motets, a Magnificat, and three chansons. Each offers an exploration of

a different musical challenge, and together they demonstrate the ways

in which La Rue was a leader in the expanding musical world of the late

fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries via his expansion of texture,

expansion of range, expansion of chromatic language, expansion of

formal possibilities, and expansion in the ways to use borrowed

material. May these recordings offer expanded joys to the listener as

well!

Masses

The Missa Sub tuum præsidium comes from La Rue's

earliest group of masses, appearing for the first time in the luxurious

manuscript copied for Philip the Fair before his final trip to Spain

(Brussels, Royal Library, Ms. 9126), where its prominent position as

the first La Rue mass in the collection, immediately after the opening

work by Josquin, suggests that it is a brand-new work. It ultimately

proved to be a highly popular one, appearing in whole or in part in

manuscripts and prints right up into the 1590s.

The work displays numerous structural characteristics typical of La

Rue's early works, with its four-voice texture, somewhat shorter

length, and standard layout for its movements with the exception of the

Sanctus. That movement has a separate Osanna II section, a rarity among

La Rue's masses. The mass is based on the well-known Marian antiphon,

but in phrygian rather than mixolydian, and imitated in all voices. La

Rue's penchant for continual variation of his motives is on full

display here, with a special emphasis on an exploration of rhythmic

mutability that makes this an especially captivating work.

Missa Ave Maria surely comes from the time after La Rue

returned from Spain in 1508, and is quite possibly from early in his

last period of composition. It is a substantial mass, as many of his

from this time are, with an emphasis now on duple rather than triple

meter. Four of the movements are for four voices, but the Credo expands

to five - an unusual move for the composer - and La Rue takes advantage

of this increase in texture to place the cantus firmus in the added

tenor voice, usually in longer note values. Such treatment is, again,

atypical for La Rue. Far more common is his integration of the chant

model into all voices so that it is indistinguishable from the

surrounding texture, as happens clearly at the beginning of all other

movements. The model is a Marian antiphon for the Feast of the

Annunciation, Ave Maria... benedicta tu, a version of which is

performed here before La Rue's mass. The joyful occasion celebrated in

the mass is perhaps the reason behind the relatively high ranges used

throughout this popular and widely-disseminated composition, which was

still being written about in the early seventeenth century.

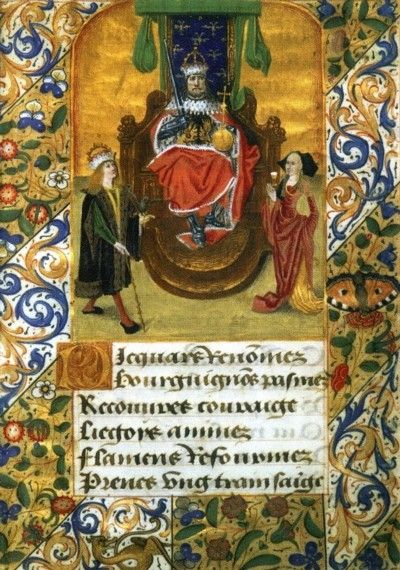

Missa Alleluia [Illustration 2] is notable for several

features. Its texture is unusually full. The use of five voices is

common enough for La Rue - he is one of the most important composers in

terms of textural expansion - but most of the time in this mass four,

and often five, of the voices are employed, making it one of his most

richly-textured works. Even more striking is his use of pre-existent

material. The "alleluia" model has yet to be identified but is quite

likely extracted from a polyphonic composition. The manuscripts

containing the Missa Alleluia frequently underlay not the mass

text for the cantus firmus, but rather the word "alleluia," and the

recording incorporates that separate text into the performance. Placed

in the tenor line in long note values, typically entering the texture

last, the cantus firmus is treated by La Rue with a strictness that is

highly unusual for him, presented in augmentation, diminution, and even

retrograde (in the Qui tollis). La Rue typically writes the

cantus firmus in standard note values and provides instructions for the

performer; thus, in the Kyrie, "In duplo" tells the performers to

double the note values, while "Vade retro sathanas" (get thee hence,

Satan), tells the performers to sing the model backwards in the Qui

tollis. But the most striking appearance is saved for the final

Agnus, where the model migrates to the highest voice. Supported by a

swirling counterpoint of tightly constructed melodic motives in the

lower voices, the sustained melodic line calls to mind the closing of

Josquin's Missa L'homme armé super voces musicales, a

composition that La Rue knew and consciously emulated elsewhere as well.

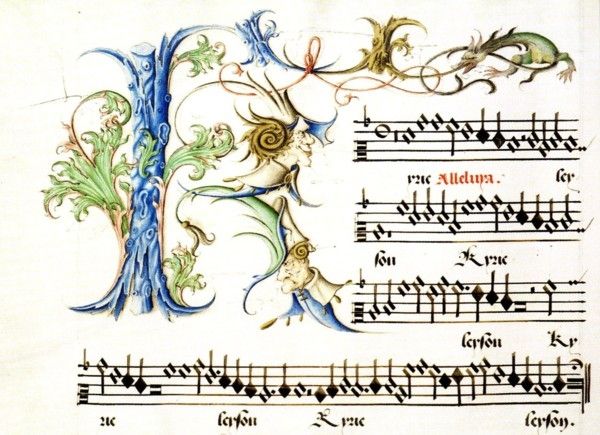

The Missa de septem doloribus [Illustrations 3-4] is a

mature mass of La Rue, written for the Feast of the Seven Sorrows of

the Blessed Virgin Mary. The feast was created in 1423 and

enthusiastically supported by the Habsburg-Burgundian court during the

composer's tenure there, making it an appropriate subject for a mass.

La Rue's five-voice composition, performed here with plainchant propers

inserted, is noteworthy for its inclusion of a copious amount of extra

text, the words of its unidentified musical models. Whereas the Missa

Alleluia inserted the word "Alleluia" at various points in the

tenor line, the Missa de septem doloribus gives the tenor a

constant stream of new text in addition to that of the mass ordinary.

The first Kyrie gives the text for the invitatory for the feast day's

Matins ("Dolores gloriose"), while the Christe provides an unidentified

text beginning "Trenosa cornpassio." Starting with the second Kyrie,

the first tenor in most of the rest of the mass receives the lengthy

text of the feast's sequence. Whether these extra texts are performed

or not - the Mass ordinary text is sometimes absent from the cantus

firmus voice in the manuscripts, suggesting that the extra text was

intended to be heard - the performers and the owners of the luxurious

sources would have read and absorbed the new words that underscored the

subject of the feast.

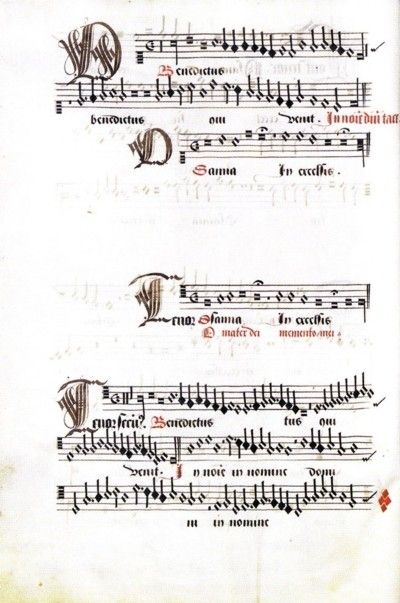

The mass has another striking borrowing in its second Osanna

[Illustration 5]. The presence of a second Osanna is a rarity for La

Rue, and this one is extraordinarily short, a mere twelve breves. The

length was prompted by its borrowed material: the superius phrase "O

mater Dei, memento mei. Amen" from the conclusion of Josquin's famous Ave

Maria... virgo serena. Transposed down a twelfth and buried in La

Rue's first tenor part, the melody is nonetheless audible to those in

the know, and in all but one of the manuscript sources the tune is

provided with the borrowed words as well. In Brussels, Royal Library,

Ms. 6428, it stands out even more by virtue of the empty parchment

surrounding the first tenor part.

Motets and Magnificat

In Ave regina cœlorum La Rue sets the text of one

of the most important Marian antiphons, yet it is difficult to find any

melodic relation in his composition to the famous melody, or for that

matter to any other known plainchant. The work is still an

extraordinarily attractive composition and likely a late work, with its

modern-sounding modality, clear points of imitation, textural variety,

and concise expression of the text. Today's listeners are not the only

ones to succumb to its charms: it was one of the most popular of La

Rue's motets in the sixteenth century.

La Rue's setting of the popular Marian antiphon Regina cœli

survives in a single Italian source. The chant model is placed in the

tenor, on F, though the signature flat expected for this melody has

been erased in the manuscript. The remaining three voices present a

modal contrast, positioned in phrygian. La Rue solves this aural

conflict by having the tenor voice drop out before the end of each

section of this bipartite work, leaving the remaining three voices to

cadence safely on E. This procedure is unusual but not unknown for the

time, with the most famous example being, yet again, Josquin's Missa

L'homme armé super voces musicales.

La Rue's six settings of the Salve regina text make him the

most prolific composer to set this important antiphon. It is the Marian

antiphon to appear most frequently in the liturgical rotation, and was

highlighted through the numerous Salve (or "Lof") services held across

the Low Countries. As with his other settings, Salve regina II

is based on the Marian antiphon, its motives scattered throughout the

texture but appearing most prominently in the tenor, where its

treatment varies from strict to free, from long held notes to rapidly

flowing movement. The varied imitation and motivic interplay among the

voices is quintessential La Rue.

The massive motet Salve mater salvatoris - 300 breves

long - sets a prayer for the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary that

has been lightly altered. The text would have had special meaning for

Margaret of Austria in her capacity as Governor of the Netherlands,

incorporating as it does the words "gubernatrix" and "Margarita." The

work is one of La Rue's many explorations of low ranges, with the top

voice using the alto clef and the lowest of the four given with an F5

clef and descending to D below the staff. Textural variety is

maintained through frequent use of duos as well as care in setting off

specific words or phrases, such as the rapid-fire exchange between high

and low pairs for "Tu Domina / angelorum / Tu Regina / seniorum / Tu

mamilla / parvulorum" (given additional emphasis through a short

excursion into triple meter) and especially the repeat of the word

"Margarita" to begin a new duet section, ensuring that La Rue's patron

would not miss his musical homage to her.

La Rue was one of the first composers to produce a complete Magnificat

cycle on all eight tones; seven of these survive. In each instance he

sets the even-numbered verses polyphonically, with the odd ones

performed in plainchant. Magnificat Quinti toni is a

typically gem-like setting, with reduced voices for verses 4, 8, and

10, and lively imitative counterpoint throughout, building to a

triple-meter conclusion.

Doleo super te is the quarta pars of La Rue's

lengthy Considera Israel, a motet almost certainly written for

Margaret on the death of her brother. This final section circulated on

its own in two sources, one of them - significantly - Margaret's

personal chansonnier, Brussels, Royal Library, Ms. 228. The full motet

sets David's lament for Jonathan from II Samuel; Doleo super te

opens with the text "I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan,"

and is thus a fitting component of Margaret's chansonnier, produced

after his death. This stunningly beautiful composition begins with

slowly-moving rhythms staggered among the four voices, and little

melodic motion to disturb the opening plaint. The piece continues with

a masterful command of shifting textures, with now one voice and then

another coming into focus, as for example when the superius sings

"unicum filium" in syncopation against the lower voices. All parts come

together only at "et perierunt arma" the approach to the conclusion,

and then one after another each voice descends by line or by leap, with

poignant falling thirds in the superius and then the bassus to generate

an ending that is no true cadence, but simply a cessation of sound.

Chansons

Pourquoy tant and Il viendra le jour

désiré [Illustration 7] were evidently intended

as a pair; they circulate one after another in their two manuscript

sources (Pourquoy tant also appears independently in Petrucci's Canti

C), and Il viendra provides an affirmative answer to the

despairing cry of Pourquoy tant. They share many stylistic

traits as well: each for four equal voices, each with similar (though

not exact) ranges, each modally based on A, each with a

(non-fixed-form) text of four lines with internal repetition, each

sharing a recurring bassus motive, each largely melismatic despite

repeated text, and each demonstrating La Rue's commitment to varietas.

Paired chansons become prominent later in the sixteenth century; La

Rue's duo serves as an important forerunner to this trend.

Pourquoy non [Illustration 8] is one of La Rue's most

impressive secular works. In keeping with the text's unhappy

sentiments, the four voices are pitched extremely low - the highest

note is only the G above middle C (the superius is written in tenor

clef!), while the lowest voice sinks to B-flat below the staff. La Rue

creates a powerful rhetorical structure for his text, with the mirrored

words of the first two lines - especially "Pourquoy non" - reflected in

almost exact musical repetition. Each of the first four phrases is

arrested by a fermata before continuing, an unheard-of beginning for a

chanson. The effect of the expanded range and the unusual formal

structure is heightened by the exploration of rarely-used accidentals.

All voices have both B-flats and E-flats in the signatures (one of the

very earliest works to have both accidentals in all voices), and the

altus, the voice that begins the composition all alone, leaps to a

signed A-flat on only its second note. Yet La Rue doesn't stop there

but goes still further: on the text "la fin" he extends the chromatic

range still further, reaching to D-flat. Range, layout, and harmony all

interact to generate a powerful setting of a despairing cry. It was one

of La Rue's most widely disseminated works (though often transposed up

a fifth, including its appearance in Odhecaton), and in

Margaret's chansonnier it is one of the few pieces to receive the

distinction of an illuminated border, a sure sign of its leading

position within La Rue's output. The song provides a concise summary of

his most powerful effects.

Honey MECONI