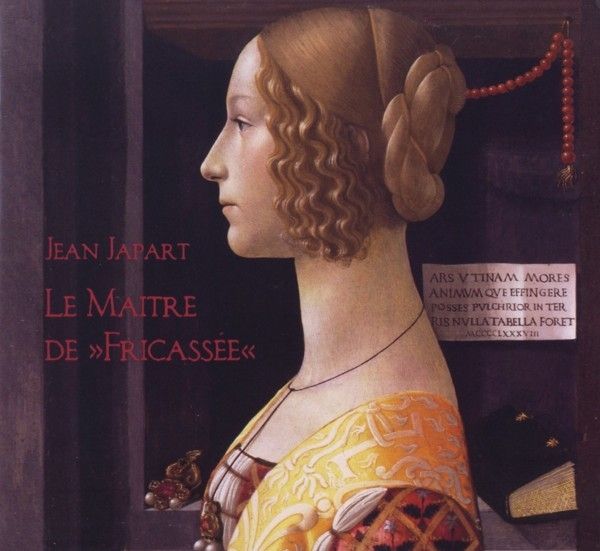

Le Maître de »Fricassée« / Les Flamboyants

Secular Music of Jean JAPART (fl. 1474-81)

medieval.org

Christophorus CHR 77353

2011

1. L'homme armé · Monodie [0:31]

2. JOSQUIN (c.1450-1521). L'omme armé · a4 [2:00]

3. Jean JAPART. Il est de bonne heure ne / Lomme armé

· a4 [1:19]

4. Jacob OBRECHT (c.1450-1505). Tant que nostre argent durra · a4

[1:28]

5. Jean JAPART (?) - Amours fait mult / Il est de bonne heure /

Tant que nostre argent · a4 [1:13]

6. Jean JAPART. Tan bien mi son pensa · a4 [2:00]

7. Jean JAPART. Pour passer temps / Plus ne chasceray

· a4 [1:42]

8. Jean JAPART. Questa se chiama · a4 [1:10]

9. Jean JAPART (?) - Jay biens nori · a3 [3:06]

10. Helas quel e a mon gre · Monodie [1:07]

11. Jean JAPART. Helas quel e a mon gre · a4 [1:27]

12. Jean JAPART. Fortuna d'un gran tempo ·

rekonstruierte Monodie [0:21]

13. JOSQUIN. Fortuna dun gran tempo · a3 [1:43]

14. Jean JAPART. Fortuna dun gran tempo · a4 [1:38]

15. Johannes MARTINI (c.1440-1497/98). Fortuna d'un gran tempo · a4

[1:49]

16. Antoine de VIGNE. Franc cœur qu'as tu / Fortuna dun gran

tempo · a5 [1:01]

17. Hayne van GHIZEGHEM (c.1445-c.1495). De tous biens playne · a3

& a4 [5:52]

18. Jean JAPART. De tous biens playne · a4 [1:41]

19. Jean JAPART (?) - Je cuide se ce tamps dure · a3

[1:43]

20. Jean JAPART. Je cuide / De tous biens · a4 [1:17]

21. Jean JAPART. Tmeskin was jonk · a3 & a4 [2:24]

22. J'ai pris amours · a3 [2:52]

23. Jean JAPART. J'ai pris amours · a4 [1:00]

24. Jean JAPART. J'ay pris amours · a4 [1:09]

Canon «Fit aries piscis in licanosyparthon»

25. Antoine BUSNOYS (c. 1430-1492). Jay pris amours · a4 [2:24]

26. Jean JAPART. Amours amours amours · a4 [2:08]

27. Jean JAPART. Nenciozza mia · a4 [2:01]

28. Jean JAPART. Prestes le moy · a4 [2:58]

29. Jean JAPART. Vray dieu d'amours / Sancte Joannes baptista /

Ora pro nobis · a5 [1:15]

30. Jean JAPART. Trois filles estoient · a3 [2:01]

31. Si congié prens (1. Strophe) [0:59]

32. Jean JAPART. Se congie pris · a4 (verse 2, anonym)

[2:30]

33. Se congie pris (3. Strophe) [2:20]

34. JOSQUIN. Se congié prens · a6 (4. Strophe)

[2:05]

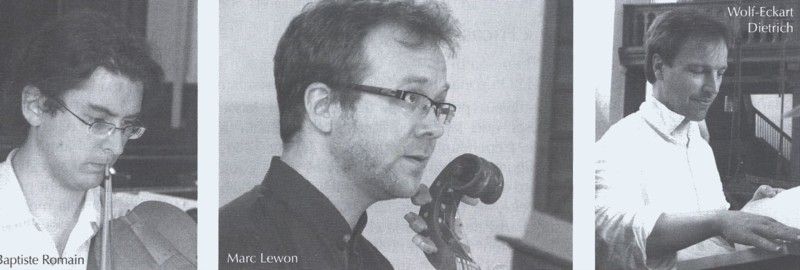

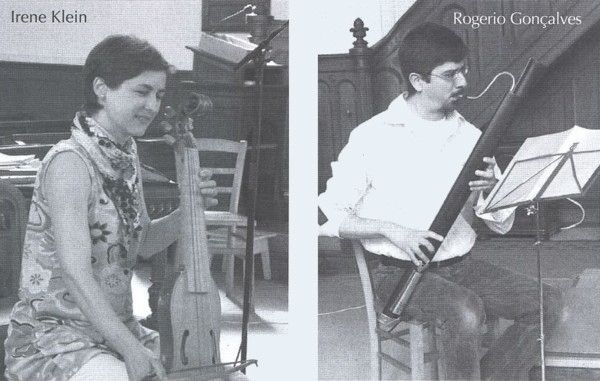

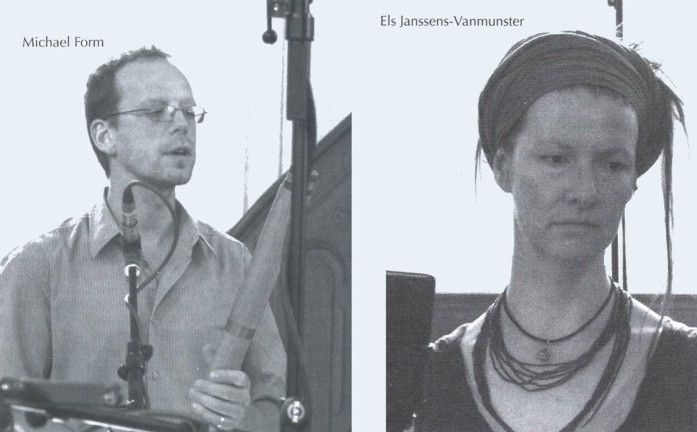

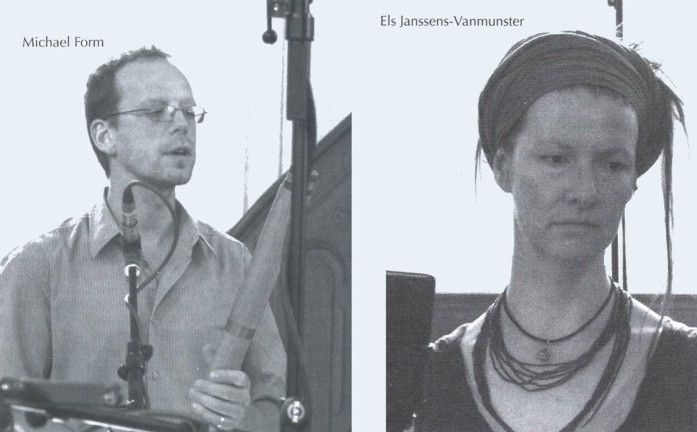

Els Janssens-Vanmunster, chant

Michael Feyfar, chant

Les Flamboyants

www.lesflamboyants.eu

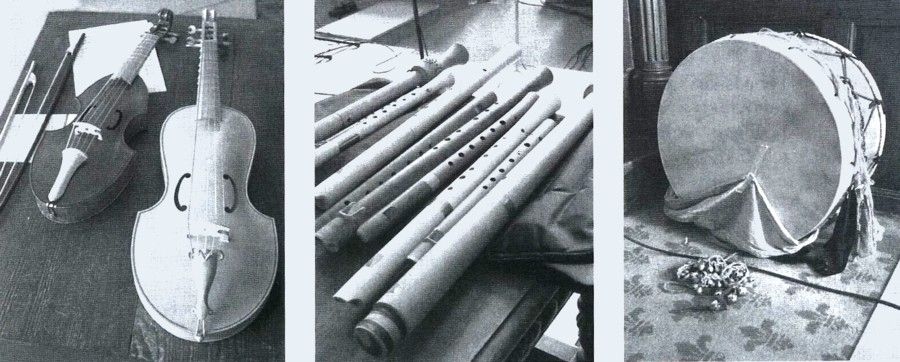

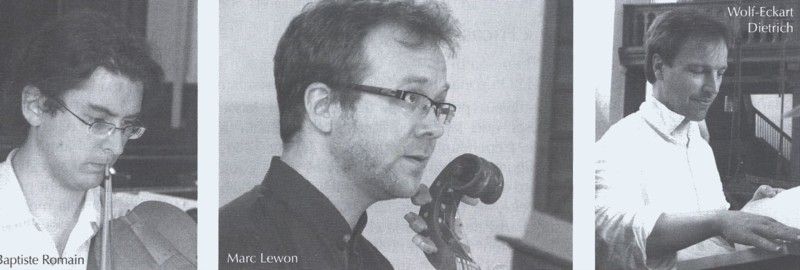

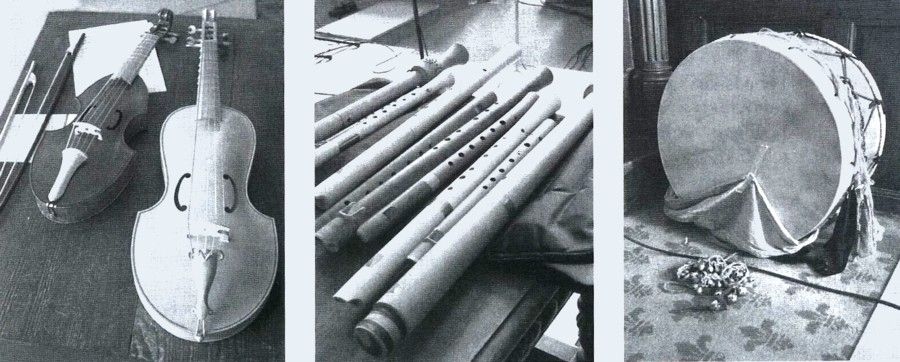

Wolf-Eckart Dietrich, clavicytherium

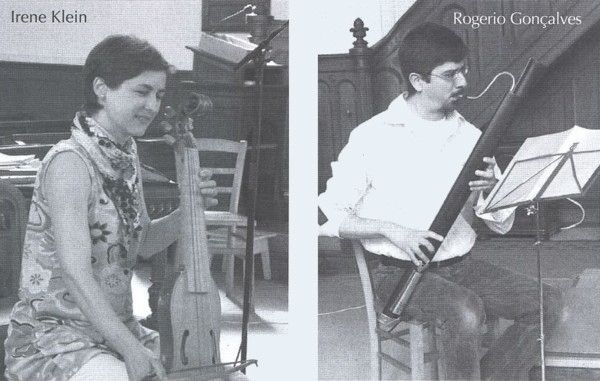

Rogerio Gonçalves, dulcian & percussion

Irene Klein, viola da gamba & viola d'arco

Marc Lewon, lute, gittem, Renaissance guitar, viola d'arco &

chant

Romina Lischka, viola da gamba

Giovanna Pessi, harp

Baptiste Romain, vielle & Renaissance violin

Silvia Tecardi, vielle & viola d'arco

Michael Form, flute & direction

Quellen:

Ottaviano Petrucci: Harmonice Musices Odhecaton

A (Venedig 1501): #5 6 11 13 17 19 21 23 25 26 27 32

Canti B. No Cinquanta (Venedig 1502): #2 16 20 24

Canti C. No cento Cinquanta (Venedig, 1503/04): #3 4 7 8 14 18 28 29 33

#9: Rom, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, C.G. XIII.27 «Cappella

Giulia Chansonnier»

#10: Paris, Bibl. Nationale, fonds fr. 12744

#15: Florenz, Bibl. Nazionale Centrale, Ms. Banco Rari 229

#17: Kopenhagen, Kongelige Bibl., Thott 291, 80, "si placet": Odhecaton

#22: Paris, Bibl. Nationale, Rés. VmC., Ms 57 «Codex

Cordiforme»

#30: Paris, Bibl. Nationale, fonds fr.15123

#34: Le Septiesme livre..., Tylman Susato, Antwerpen 1545

Executive producer DRS 2: Annelise Alder

Executive producer MusiContact: Joachim Berenbold

Recording: 23.-29. June 2010, Temple St. Jean, Mulhouse (France)

Recording producer & digital editing: Michaela Wiesbeck

Editor & layout: Joachim Berenbold

Translation: Lindsay Chalmers-Gerbracht (English)

English liner notes

Jean

Japart

Hommage an den Meister des „Fricassée"

von Michael Form

Jean Japart gehört zu den großen Unbekannten der

franko-flämischen Schule des späten 15. Jahrhunderts. Dabei

zeichnet sich seine Musik durch überraschende Wendungen, gewagte

Harmonik und kühne Satzstrukturen aus, die den Hörer des 21.

Jahrhunderts in Erstaunen versetzen. Freilich erfüllt Japart nicht

die Voraussetzungen, um in den klassischen Kanon der

<unsterblichen> Alten Meister aufgenommen zu werden. Er hat weder

Messen noch groß angelegte Motetten wie Josquin, Obrecht,

Ockeghem oder Isaac geschaffen, sondern sich ausschließlich den

kleinen weltlichen Formen der Chanson und der Instrumentalmusik

gewidmet. Außerdem ist sein erhaltenes Œuvre kaum

umfangreich genug, um mit ihm ein Konzertprogramm zu füllen.

Über Japarts Lebenslauf ist zudem nur sehr wenig bekannt.

Vermutlich wurde er um 1450 in der Picardie, im heutigen

Nordfrankreich, geboren. Unter den nach dem Mord an Galeazzo Maria

Sforza 1476 entlassenen Musikern der Mailänder Hofkapelle befindet

sich ein gewisser <Johanne haeppart>, bei dem es sich vermutlich

um Japart handelt. Schlaglichtartig tritt er uns als hoch angesehener

(und ebenso hoch bezahlter) Sanger am Hof von Ercole I. d'Este in

Ferrara entgegen, einem Brennpunkt musikalischer Hochkultur im letzten

Drittel des 15. Jahrhunderts. In Ferrara wird er am 1. April 1477 zum

ersten Mal erwähnt. Dass er besondere fürstliche Gunst

genoss, geht aus Dokumenten aus den Jahren 1479 und 1480 hervor, welche

die finanzielle Unterstützung durch Ercole beim Erwerb eines

Hauses belegen. Dies lässt vermuten, dass Japart vorhatte, in

Ferrara sesshaft zu werden. Jedoch wird er ab dem 1. Februar 1481 nicht

mehr unter den Ferrareser Hofmusikern geführt. Danach verlieren

sich seine Spuren. Ihn mit Gaspar van Weerbeke, dem von Galeazzo mit

der Rekrutierung der Mailänder Hofkapelle beauftragten

flämischen Musiker zu identifizieren, ist wohl genau so

spekulativ, wie ihm in <Jaspare>, einem sangmeester an

der Liebfrauenkirche in Bergenop-Zoom 1504-08 wiederbegegnen zu wollen.

Nicht zuletzt ist eine Zeitspanne von 23 Jahren zu lang, in welcher der

Werdegang eines scheinbar hoch geschätzten Musikers im Dunkeln

liegen würde. Das Fehlen biographischer Informationen lässt

vielmehr vermuten, dass Japan unerwartet in Ferrara gestorben ist.

Josquin Desprez' Chanson, «Revenue d'outre monts, Japart/Je

n'ai du sort que mince part», ist eine Deploration auf dessen

Tod. Leider ist das Werk verloren gegangen, so dass mit Hilfe

stilistischer Untersuchungen keine zeitliche Einordnung möglich

ist, um über diesen Umweg auf Japarts Todesjahr zu

schließen. Bemerkenswert bleibt indes, dass Josquin nur einem

einzigen anderen Komponisten einen musikalischen Nachruf gewidmet hat,

nämlich dem großen Johannes Ockeghem. Wo sich die beiden

Musiker begegnet sein könnten, ist unklar, zumal wenn man den Tod

Japarts auf die Zeit kurz nach 1481 ansetzt, denn Josquin reiste nicht

vor 1480 nach Oberitalien und hatte seine Festanstellung am Ferrareser

Hof erst ab 1503. Insofern muss die Frage, ob sich die beiden Musiker

überhaupt persönlich gekannt haben, offen bleiben.

Gegen ein frühes Todesjahr spricht der prominente Status, den

Ottaviano Petrucci Jean Japart in seinem monumentalen dreiteiligen

Notendruck, den Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A (1501), den Canti

B numero cinquanta (1502) und den Canto C numero cento cinquanta

(1503/04) eingeräumt hat: Japarts Œuvre umfasst 23 textlose

Chansons (darunter sechs mit widersprüchlicher Zuschreibung),

davon wurden 21 von Petrucci gedruckt. Falls Japan tatsächlich

1481 oder kurz danach gestorben ist, dann wäre er einer der

wenigen Komponisten, die zum Zeitpunkt der Drucklegung schon viele

Jahre tot waren. Ansonsten wurden nur Antoine Busnoys, Johannes

Martini, Johannes Ockeghem, Johannes Regis und Hayne van Ghizeghem

diese posthume Ehre zuteil. Jedoch ist keiner dieser Komponisten, die

das 16. Jahrhundert nicht erlebt haben, mit so vielen Werken vertreten

wie Japart. Selbst Alexander Agricola und Josquin Desprez, die

bedeutendsten Meister ihrer Zeit, stehen quantitativ nach. Der aktuelle

Stand der Forschung kann für diese vermeintliche Diskrepanz (noch)

keine Lösung anbieten.

Zwei stilistische Merkmale sind für Jean Japarts Kompositionsstil

besonders charakteristisch: das Quodlibet und der Rätselkanon.

Japarts außergewöhnliche kontrapunktische Begabung findet

ihren Niederschlag in kunstvollen Quodlibets (franz. fricassées),

in denen er mehrere bereits existierende, meist bekannte Lied-Melodien,

miteinander kombiniert. Zu einem klingenden gordischen Knoten steigern

sich Stücke wie Amours fait mult/Il est de bonne heure/Tant

que nostre argent, in denen er nicht weniger als drei verschiedene

Melodien übereinander schichtet, die bereits von Zeitgenossen zu

polyphonen Sätzen verarbeitet wurden. Diese Technik des Zitierens

ermöglicht es, eine Vielzahl von Bezügen zu schaffen, die wir

in der vorliegenden Einspielung in Form von ,Suiten', die auch Werke

anderer Komponisten einbeziehen, musikalisch hörbar machen. Vray

dieu d'amours/Sancte Joannes baptista/Ora pro nobis, ebenfalls ein

Quodlibet besonderen Charakters, könnte Japarts Beitrag zu einem

kompositorischen Wettstreit gewesen sein; zumindest sind ganz

ähnliche Stücke von Heinrich Isaac und einem anonymen

Komponisten überliefert: In den jeweils fünfstimmigen

Sätzen wird die Litanei der Heiligen mit einer weltlichen

Chanson-Melodie konfrontiert.

Unter Rätselkanons versteht man Stücke, bei denen zumindest

eine Stimme anders aufgeführt wird als sie notiert ist, wobei dies

mitunter einer verbalen Anleitung bedarf. In ihrem musikalischen

Diskurs zu J'ai pris amours liefern sich Japart und Antoine

Busnoys ein besonderes Spiel: Während Busnoys den Tenor dieser

anonymen Chanson in freier Umkehrung der Intervalle („au

rebours") durchführt, bringt Japart die Cantus-Stimme im Krebsgang

— allerdings in die Bassstimme verlegt und um das Intervall einer

Duodezime nach unten transponiert. Bemerkenswert ist der notengetreue

Rückwärtslauf sowohl der Melodie als auch des Rhythmus'. Um

sicher zu stellen, dass trotz dieser Verfremdung die ursprüngliche

Chanson erkennbar bleibt, verstreut Japart Bruchstücke der

originalen Cantus-Stimme in den drei Oberstimmen. In De tous biens

playne hingegen kehrt Japart die Tenormelodie um. Durch die

kompromisslose Respektierung der originalen Intervallverhältnisse

ergeben sich exotische, mitunter sperrige kontrapunktische Wendungen.

Darüber hinaus hatte Japart eine Vorliebe für Sätze, in

denen zwei Stimmen streng kanonisch geführt werden. In Pour

passer temps/Plus ne chasceray sans gans provoziert dies eine

Fülle von relationes non harmonicae, die aus der strengen

Kanonführung der Mittelstimmen (Tenor und Contratenor)

resultieren. Immer wieder ergeben sich Klauseln an untypischen Stellen,

die entweder zu für Japarts Epoche altmodischen

Doppelleittonkadenzen führen oder zu unvermeidbaren, scharfen

Querständen. Gemeinsam mit Vorhaltsbildungen, die erst im 17.

Jahrhundert üblich werden, entsteht eine fast manieristische

Musik, die sich spielerisch disparater Floskeln bedient.

Jean

Japart

An Homage to the Master of the "Quodlibet"

by Michael Form

Jean Japart remains one of the "great unknowns" of the Franco-Flemish

school of the late fifteenth century. His music is characterised by

several unusual features such as daring harmony and bold contrapunctual

structures, which even strike a modern audience. However Japart does

not fulfil the classical requirements to be included in the canon of

the 'immortal' Old Masters: He composed no masses or large-scale motets

like his contemporaries Josquin, Obrecht, Ockeghem and Isaac, but

devoted himself exclusively to smaller secular forms such as the

chanson and instrumental music. Moreover his entire compositional

oeuvre could scarcely fill a concert programme.

There is also very little known about Japart's biographical details. He

was probably born around 1450 in Picardie, now a region of northern

France. Among the musicians of the Court Chapel in Milan dismissed in

1476 after the murder of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, there is mention of a

certain 'Johanne haeppart' which presumably refers to Japart.

Historically speaking, the first documented reference to Japart dates

back to 1 April 1477 where we encounter him as an already highly

acclaimed (and equally highly paid) singer at the court of Ercole I

d'Este in Ferrara, a major centre of intense musical culture in the

last third of the fifteenth century. Additional documents from 1479 and

1480 reveal that he enjoyed special ducal favours bestowed by Ercole

concerning financial support for the acquisition of a house which would

suggest that Japart was intending to settle permanently in Ferrara. His

name is however no longer included in the list of court musicians at

Ferrara after 1 February 1481, and at this point we lose all subsequent

traces of the composer. Speculation identifying him as Gaspar van

Weerbeke, the Flemish musician commissioned by Galeazzo to recruit

members of the court chapel in Milan, is just as tenuous as the

possibility that he could have resurfaced as 'Jaspare', a sangmeester

at the Liebfrauenkirche [Church of Our Lady] in Bergen-op-Zoom between

1504 and 08. Nevertheless, a period of 23 years with no further mention

of the ongoing career of this apparently greatly respected musician is

too long to be plausible; the lack of any additional biographical

documentation would suggest that Japart died unexpectedly in Ferrara.

Josquin Desprez' chanson, «Revenue d'outre monts, Japart/Je n'ai

du sort que mince part», is a lamentation on the composer's

death: Unfortunately this work has now been lost, preventing a

stylistic examination which could perhaps have indirectly narrowed down

the period of time during which Japart's death could have occurred. It

is, however, remarkable that Josquin only wrote one other musical

obituary, namely on the death of the great Johannes Ockeghem. Where

Josquin and Japart could have met also remains unclear, particularly if

the death of Japart is estimated to have occurred shortly after the

year 1481, as Josquin did not travel to northern Italy before 1480 and

only took up a post at the court in Ferrara in 1503. The question as to

whether both composers were actually personally acquainted with one

another must therefore remain unanswered.

Counter-evidence for the early death of Japart is provided by the

prominent status given to the composer by Ottaviano Petrucci in his

monumental musical publication in three volumes, the Harmonice

Musices Odhecaton A (1501), the Canti B numero cinquanta

(1502) and the Canti C numero cento cinquanta (1503/04).

Japart's complete oeuvre encompasses 23 chansons without text

(including six with contradictory attribution), of which Petrucci

printed 21 of these works in his anthology. Should Japart actually have

died in or around 1481, this would make him one of the few composers to

have been long dead at the time of printing of these volumes: only

Antoine Busnoys, Johannes Martini, Johannes Ockeghem, Johannes Regis

and Hayne van Ghizeghem shared this posthumous honour. However, none of

the composers who had died before 1500 rival Japart output in these

volumes; even Alexander Agricola and Josquin Desprez, the most eminent

masters of their time, are quantitatively less well represented. The

status of current research cannot (yet) offer a solution for this

putative discrepancy.

Jean Japart's compositional style is characterised by two distinct

features: the quodlibet and the enigma canon. His extraordinary gift

for counterpoint is manifested in elaborate quodlibets (Fr.: fricassées)

in which he intertwines several pre-existing and already well-known

melodies. Pieces such as Amours fait mult/Il est de bonne

heure/Tant que nostre argent form an intricate musical Gordian knot

with no fewer than three different melodies layered above one another

which had already been set to polyphonic versions by Japart's

contemporaries. This particular technique of quotation creates a dense

web of intertextual relationships which are emphasized in the present

recording through the compilation of several pieces into 'suites',

incorporating music by other composers. Vray dieu d'amours/Sancte

Joannes baptista/Ora pro nobis, another quodlibet of unique

character, could have served as Japart's contribution to a

compositional contest; very similar works by Heinrich Isaac and an

anonymous composer have also survived. The five-part settings juxtapose

the Holy Litany with a secular chanson melody.

Enigma canons are pieces in which at least one part is performed

differently than notated and therefore calls for explanatory notes.

Japart and Antoine Busnoys engage in subtle games in their musical

discourses on J'ai pris amours: Busnoys sets the tenor part of

this famous, although anonymous chanson in a free inversion of

intervals ("au rebours"), but Japart not only sets the cantus as a

retrograde canon and moreover places it on the bass line transposed

down by an octave and a fifth. The note-for-note reversal of both

melody and rhythm are indeed remarkable. To ensure that the original

chanson remains recognisable despite its obscuration, Japart scatters

fragments of the original cantus among the three upper voices. In

contrast, the tenor melody in De tous biens playne is inverted:

The uncompromising inversion of the original intervals produces exotic

and at times rough contrapuntal turns.

Japart also had a predilection for musical structures in which two

voices were constructed in strict canon. In Pour passer temps/Plus

ne chasceray sans gans for example, this produces an abundance of relationes

non harmonicae resulting from the strict canonical imitation of the

two middle voices (tenor and contratenor). This creates a number of

clausulas occurring at untypical places either resulting in double

leading tone cadences, a somewhat old-fashioned feature in Japart's

era, or in unavoidable harsh harmonical relations. All this combined

with suspensions which were not customary until the seventeenth century

results in an almost manneristic musical character.