medieval.org

worldcat.org

Bard BDCD 1-91 06

1991

A Medieval Christmas

medieval.org

worldcat.org

Bard BDCD 1-91 06

1991

A Medieval Christmas

The

Folger Consort presents a stirring selection of Christmas music from

late 11th-century southern France to 15th-century England.These are

pieces of wonderful variety — intimate and inspiring, courtly and

rustic, complex and engagingly simple. Yet this rich diversity of music

shares the telling of the Christmas story.

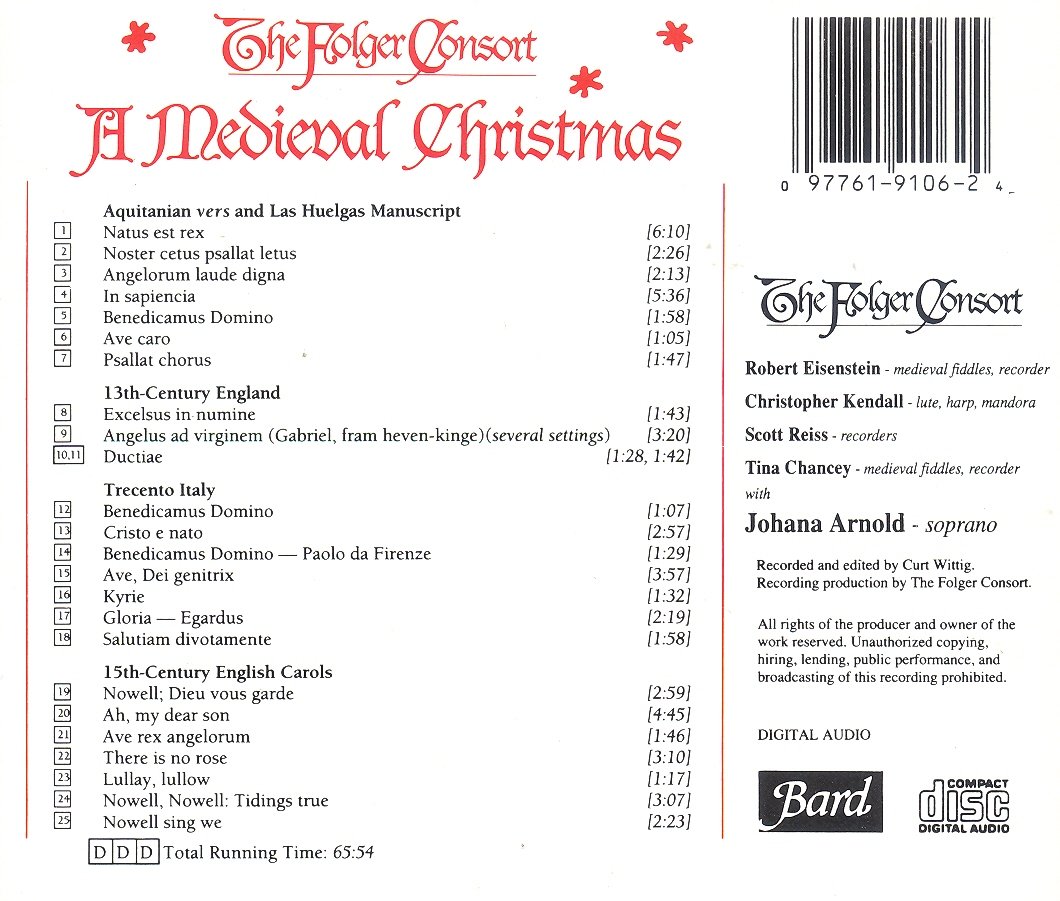

Aquitanian vers and Las Huelgas Manuscript

1. Natus est rex [6:10]

2. Noster cetus psallat letus [2:26]

3. Angelorum laude digna [2:13]

Hu 60

4. In sapiencia [5:36]

Hu 62

5. Benedicamus Domino [1:58]

Hu 37

6. Ave caro [1:05]

Hu 136

7. Psallat chorus [1:47]

Hu 123

13th-Century England

8. Excelsus in numine [1:43]

9. Angelus ad virginem [3:20] ‘Gabriel, fram heven-kinge’, several settings

10. Ductia [1:28]

11. Ductia [1:42]

Trecento · Italy

12. Benedicamus Domino [1:07]

13. Cristo e nato [2:57]

14. Benedicamus Domino [1:29] PAOLO da FIRENZE

15. Ave, Dei genitrix [3:57]

16. Kyrie [1:32]

17. Gloria [2:19] EGARDUS

18. Salutiam divotamente [1:58]

15th-Century English Carols

19. Nowell; Dieu vous garde [2:59]

20. Ah, my dear son [4:45]

21. Ave rex angelorum [1:46]

22. There is no rose [3:10]

23. Lullay, lullow [1:17]

24. Nowell, Nowell: Tidings True [3:07]

25. Nowell sing we [2:23]

Note: unless marked, compositions are anonymous

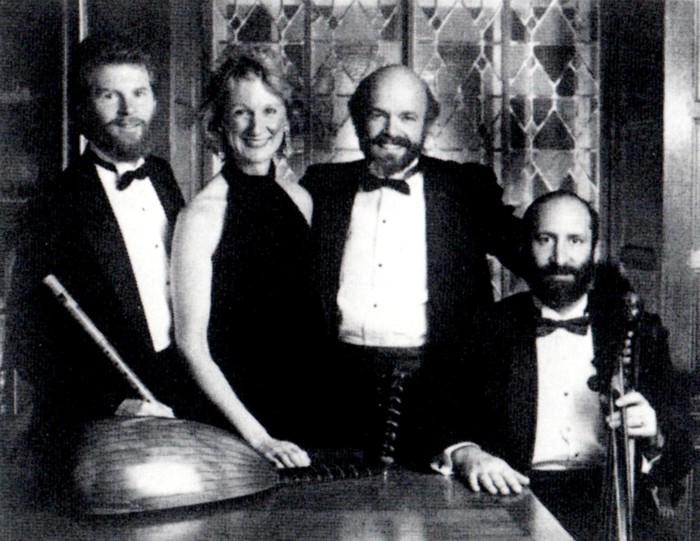

THE FOLGER CONSORT and Johana Arnold / photo: Mary Noble Ours

The

Folger Consort is ensemble-in-residence at the Folger Shakespeare

Library, a leading center for medieval and Renaissance studies in

Washington, D.C. Founding members of the Consort are Robert Eisenstein, rebec, vielle, recorders,

Christopher Kendall, lute, harp, mandora, and Scott Reiss, recorders, psaltery, percussion.

Joining the Consort on this recording are Johana Arnold, soprano, and Tina Chancey, rebec, vielle, kamenc, recorder.

For

further information on the Folger Consort, contact the Division of

Museum and Public Programs at the Folger Shakespeare Library, 201 East

Capitol Street, S.E., Washington, D.C. 20003 (202) 544-7077; fax (202)

544-7520.

Werner Gundersheimer, Director, Folger Shakespeare Library

Janet Alexander Griffin, Producer, Folger Consort

Susanne Oldham, Manager, Folger Consort

DDD

Recorded in Abbey Chapel, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts

Recording and editing engineer: Curt Wittig.

Producer: The Folger Consort

Edit producer: Scott Reiss

Session producer: Ronn McFarlane

Designer: Jeanne Krohn

© and ℗ 1991 Bard Records.

All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication is a violation of applicable laws. Made in the U.S.A.

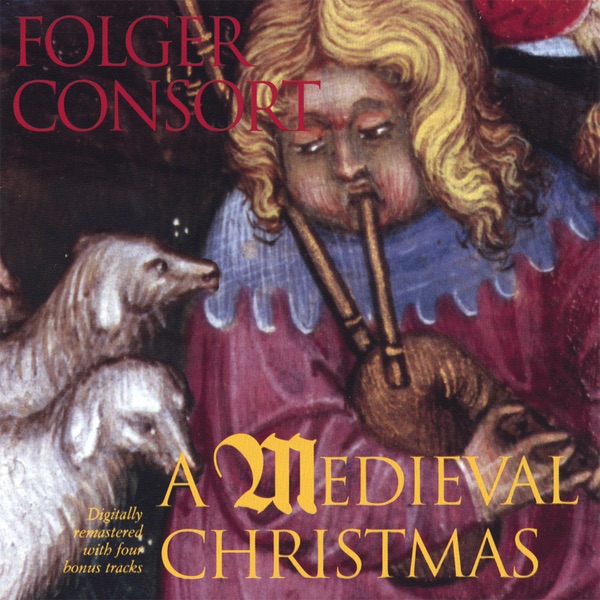

The front cover illustration is from a book of hours presented by Anne of Cleves to Henry VIII;

Enchiridion Preclare Ecclesie Sarisburiensis (Paris, ca.1533)

in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

This collection of Christmas music spans the late 11th century in

southern France to the 15th century in England. The selections show a

great variety of musical styles, learned and rustic, complex and

engagingly simple; yet most of these pieces have the telling of the

Christmas story in common. It is striking that a 14th-century laud from

Florence can appeal to us in some of the same ways as a much later carol

from England. While almost all of the works you will hear, both

instrumental and sung, are directly connected to Advent or Christmas

itself, we have rounded out the program of carols and liturgical pieces

with a few instrumental selections which seem to fit the spirit of the

season. We hope the result is a pleasing sort of international musical

smorgasbord, a holiday buffet for the ears.

Natus est rex and Noster cetus psallat letus are 11 th-century vers,

non-liturgical religious songs that survive in a manuscript from the

great library of the Abbey of St. Martial in Limoges, south-central

France. Because this area, home to the first troubadours, was important

in the development of secular song in the vernacular, its major role in

Latin song and early polyphony is often not realized. How these pieces

were performed and in what context are open questions. They may have

been sung by monks for recreation or as additions to liturgical

services. It is amazing how many of the St. Martial texts refer to

"harmonia" and "symphonia," suggesting the use of instruments and simple

polyphony in performance. The second of our two vers

is polyphonic — the first line of music creates a two-part

texture with the second line, the third with the fourth, and so on.

The

manuscript preserved at the Castilian monastery of Las Huelgas dates

from the 14th century. It is an anthology of earlier music, some as old

as the 12th century. Many pieces in this large source belong to the

French and particularly Parisian repertory of the 13th century, but

there are numerous examples of native Spanish work as well. One

interesting thing about the Las Huelgas codex is that it is written in

much less ambiguous notation than most earlier sources containing

similar music. All of our examples, except the beautiful prosa, In sapiencia, are polyphonic, and demonstrate the powerful and beautiful effects these composers could achieve with very limited means.

The English pieces performed here instrumentally are not really Christmas pieces at all. Excelsus in numine

is a motet in honor of St. Thomas of Canterbury, although the radiant,

luminous quality of the piece reflects the mood of the season. The

concluding English works are two of three such pieces preserved in modal

notation without texts. They have always been presumed to be

instrumental works, probably dances. The fact that they are virtually

indistinguishable from parts of texted conducti of the time encourages some of us to look to the large conductus repertoire as a way to extend the very limited surviving body of medieval instrumental music. Angelus ad virginem (Gabriel, fram heven-kinge),

in addition to being an Advent song, has the distinction of being the

one piece of music that has a direct association with Geoffrey Chaucer.

The dandy young scholar in "The Miller's Tale" sings it to the

accompaniment of a psaltery in order to charm his lady visitors. There

are several surviving versions, all of which may be heard here.

Although

we usually think of 14th-century music as predominantly polyphonic, it

is worth noting that polyphony was the exception rather than the rule in

most churches in Italy during this time. It was cultivated only by a

very small circle of musicians and cognoscenti. The

instrumentally performed works in this group are from the very few late

14th-century Italian sources of liturgical polyphony, and show a decided

French influence. The opening Benedicamus Domino is in a

style more appropriate to the 13th century, and probably does date from

that period. Paolo's setting of the same text is the only one of our

polyphonic selections written in the style of Italian madrigals of the

time. The Kyrie and Egardus' Gloria are much more like French mass movements. The sung tunes are laude,

that is, popular, folk-like songs which may have been used in street

processions. Melodically, these engaging pieces seem to reveal the

influence of the troubadours, Gregorian chant, and perhaps folk song. Laude

were used, if not sometimes written, by the wandering groups of

penitents which arose because of the devastating wars and plagues

between 1250 and 1350. These people sought to atone for the sins of the

world by flagellating themselves, as well as by singing. Our examples,

fortunately, are celebratory in nature, so we need not imagine tortuous

original performances.

In early 15th-century England, the Church

had by no means completely succeeded in its struggle against native

paganism. Especially among the common people, customs and beliefs from

the old religion were still maintained. The medieval Church dealt with

this problem in many ways. Some customs, such as the hanging of wreaths

of mistletoe and ivy, were simply absorbed and became integral parts of

popular Christianity. To reach the largely illiterate masses, however,

the Church had to use every possible attraction. Important feasts,

especially Christmas, were made as elaborate and eye-catching as

possible, with colorful processions and much music to ornament the

liturgy. The first Christmas carols have their origins here. Their basic

purpose was to involve the people in the Church through instructive

texts, beautiful melodies, and dance-like rhythms. The word carole in

previous centuries referred to a dance song, and the dance-like quality

still seems present in many of these 15th-century examples. At any rate,

the anonymous composers of these carols certainly must have achieved

their aims. The simple, warm beauty and lively motion of these songs

capture perfectly a Christmas spirit that has not changed since the 15th

century.

Robert Eisenstein

medieval.org

worldcat.org

cdbaby.com

Bard 837101 4415 3 7

2007

Digitally remastered with four bonus tracks

from Sing heigh, Ho! Unto the green holly!

before 'old' track#1, Natus est rex:

1 • Lux Hodie...orientis Partibus [2:21]

after 'old' track #25, Nowell sing we:

27 • Noel, Nowell: I Am Here, Sire Christesmas [2:14]

28 • Abide [1:05]

29 • The Boares Head [3:12]