JERZY DANIELEWICZ

|

Płyta, którą prezentuje Ośrodek Praktyk Teatralnych Gardzienice

wraz z Maciejem Rychtym, jest ważnym i niecodziennym wydarzeniem

artystycznym. Oto spelnia się marzenie miłośników

starożytności: usłyszenia pokaźnej liczby fragmentów muzyki

starogreckiej w jej autentycznym i pełnym (choć z konieczności

częściowo odtworzonym) brzmieniu, a przy okazji — serii niezwykle

interesujących melodii inspirowanych antykiem. Współczesny kompozytor, obdarzony niezwykłą intuicją, jaką daje tylko prawdziwa wiedza i perfekcyjne wczucie się w systemy właściwych dawnym skalom współbrzmień uzupełnił zaginione sekwencje dźwięków w zachowanych fragmentarycznie utworach, twórczo rozwinął niektóre charakterystyczne motywy, w pomysłowy sposób rozpisał je na głosy i dodał parę kongenial-nych kompozycji własnych, a wykonawcy-artyści ożywili całość wyrafinowaną harmonią gtosów, rytmem, pulsującą ciszą pauz, brzmieniem troskliwie dobranych instrumentów. To, co slyszymy, obala stereotyp szacownego zabytku. Ta muzyka oszałamia swoją spontanicznością i zaskakuje skalą nastrojów: od apollińskiego ładu i dostojeństwa do dionizyjskiego rozbuchania i żaru. Ponad 47 minut nagrania ani przez moment nie nuży, lecz przeciwnie — nieustannie fascynuje słuchacza, uskrzydla jego wyobraźnię, przenosi go w świat wiecznie żywej kultury Greków. Ci, którzy mieli szczęście uczestniczyć w spektaklu Metamorfozy Ośrodka Praktyk Teatralnych Gardzienice, obficie wykorzystującym antyczny material muzyczny, doświadczyli takiego przeżycia w jeszcze wyższym stopniu, gdyż przemawiał do nich dodatkowo taniec, gest, magia bezpośredniego oddziaływania aktorów. Tak właśnie najczęściej wykonywano dzieła greckiej mousike, poezji śpiewanej z towarzyszeniem instrumentów muzycznych, a w przypadku meliki chóralnej także tańczonej; czysto instrumentalne popisy były domeną nielicznych profesjonalistów. Nagranie niniejsze, choć oparte częściowo na rekonstrukcji, ma wartość naukowego przybliżenia; partie wcielone w gardzienicki spektakl teatralny wzbudziły niekłamany podziw specjalistów. Jego wysłuchanie będzie jednak niewątpliwie ucztą duchową również dla innego odbiorcy — miłośnika oryginalnej i intrygującej muzyki, nie nastawionego wyłącznie na historyczną ścisłość dokumentu. Jestem przekonany, że ta płyta już w chwili swoich narodzin może być zaliczona do klasyki gatunku. JERZY DANIELEWICZ |

This recording, presented by the Centre for Theater Practices Gardzienice with composer Maciej Rychły, is an important and significant artistic event.

It fulfils the dream of the many lovers of Antiquity to listen to a

number of fragments of ancient Greek music in its full and authentic

(though, out of necessity, partially reconstructed) shape, and also to

get acquainted with a series of extremely interesting tunes and melodies

inspired by ancient music. The contemporary composer, led by intuition based on deep and genuine knowledge and a full understanding of old scale systems, managed to reconstruct sequences missing in the notation of musical fragments; he also creatively developed some of the characteristic motives, skilfully set them in parts, and added a few of his own congenial compositions. Performers, in their turn, managed to bring the music to life, exhibiting a refined harmony of voices and evocative rhythm combined with the sound of carefully chosen instruments and intermittent, pulsating, and expectant silences. What we actually get to hear does not correspond to our idea of a reverend relic. This music is astonishing in its spontaneity and surprising in the sheer scale of moods that it is capable of expressing, from Apollinean order and dignity to Dionysian heat and passion. For the entire forty-seven minutes the recording does not tire in any way; on the contrary, the music constantly enraptures the audience, inspires their imagination, and transports them into the everlasting world of Greek culture. Those fortunate enough to have participated in the production of Metamorphoses, staged by the Centre for Theater Practices Gardzienice, which fully utilized the musical material, experienced this to an even higher degree, as their encounter was additionally enriched by dance, movement, and the sheer magic of the immediate interaction with performers. This is how the Greek mousike was performed most often: poetry was sung to the accompaniment of musical instruments and, in the case of choral pieces, it was also danced. Purely instrumental music remained a domain of very few professionals. This recording, regardless of the inevitable partial reconstruction, has also an academic value — that of a scholarly approximation; fragments that appeared in the theatre production received genuine specialist acclaim. It will also, however, undoubtedly prove to be a real feast for a different type of recipient, not necessarily a historical specialist, who simply loves original and intriguing music. I am truly convinced that this recording, classical from its very beginning, is soon going to attain a deserved renown. JERZY DANIELEWICZ |

|

Gdyby istniały nuty z zachowaną muzyką antycznej Grecji mielibyśmy

dzisiaj mnóstwo zespołów wykonujących te dawne

kompozycje. To pewne. Pokusa, by usłyszeć brzmienia antyku rośnie. Kto

raz połknął bakcyla, tego uleczyć może już tylko żywioł dźwięku. Po raz pierwszy usłyszałem kilka dźwięków kitary i chór śpiewający antyczną greką w latach siedemdziesiątych, kiedy profesor Jan Stęszewski przesłuchiwał taśmy przywiezione przez Sycylijczyka, Paola Carapezzę. Nowoczesna muzyka starożytności rozbudziła moje marzenia, by uchwycić kiedyś jej barwę żywą. Czasem marzenia się spełniają. Droga Arche wiodła mnie początkowo przez Słowiańszczyznę. W latach siedemdziesiątych spotykałem się z archeologami. Rekonstruowałem wykopane przez nich instrumenty i wykorzystywałem je potem w muzyce tworzonej z zespołem Kwartet targi. Krąg wędrówek rozszerzał się. Z czasem dotarłem na Bałkany, do Grecji, na południe Włoch. W Metaponto oglądałem wydobytą z grobu muzyka lirę. W takich miejscach jak Syrakuzy, czy Taormina czułem tchnienie, puls antyku. Dotarłem tam, skąd przyjechał kiedyś Carapezza. Starożytnyich zabytków muzycznych mamy niewiele — około 50 okruchów. Większość zapisów spopielił czas. Strawił ogień. Złupił barbarzyńca. Pozostały strzępy. Jak napis na grobowcu Seikilosa:

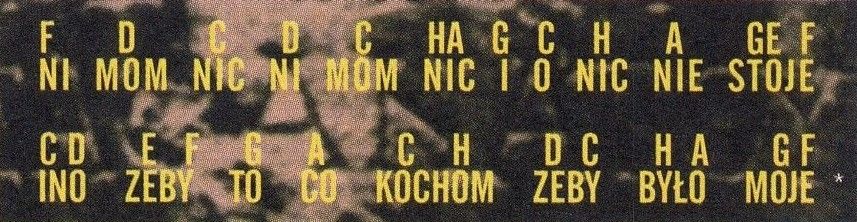

Dopóki żyjesz, lśnij, Nad sylabami słów umieszczono litery. Oznaczają one wysokości dźwięków, na których trzeba wypowiadać samogłoski czytając/śpiewając tekst. Dziś taki zapis mógłby wyglądać tak: |

Had the notation of ancient Greek music been preserved, we would have today

a plethora of groups and ensembles performing those early compositions;

that's for sure. The temptation to hear the sound of Antiquity

is rising. Who once caught the virus can only be healed by, and through,

the living sound. I first heard the sounds of the kithara and a choir performing in ancient Greek when listening, in the 1970s, with Professor Jan Steszewski to tapes brought over by the Sicilian Paolo Carapezza. This modern ancient music inspired my dream of capturing, at some point, its living brilliance. Sometimes dreams do come true. The path of Arche led me, first of all, through the Slavic territory. I had met up with archaeologists in the seventies. On many occasions, I had reconstructed excavated instruments and used them in the music created with the Jorgi Quartet (Kwartet Jorgi). My horizons broadened gradually and, in time, I reached the Balkans, Greece, and southern Italy. In Metaponto I saw a lyre discovered in a grave of a musician. In places such as Syracuse or Taormina I felt the breath and pulse of ancient times. Finally, I arrived at the place where, some time ago, Carapezza came from. We have very few musical remains from the ancient era — about fifty fragments altogether. The majority of written records have been destroyed by time; ravaged by fire; stolen by barbarians. All that remains are mere crumbs. Such as the inscription on the stela of Seikilos:

While you're alive, shine, Letters were placed above syllables. They indicated the pitch of vowels that was required in the reading/singing of the text. Such notation might today look as follows: | |

| ||

|

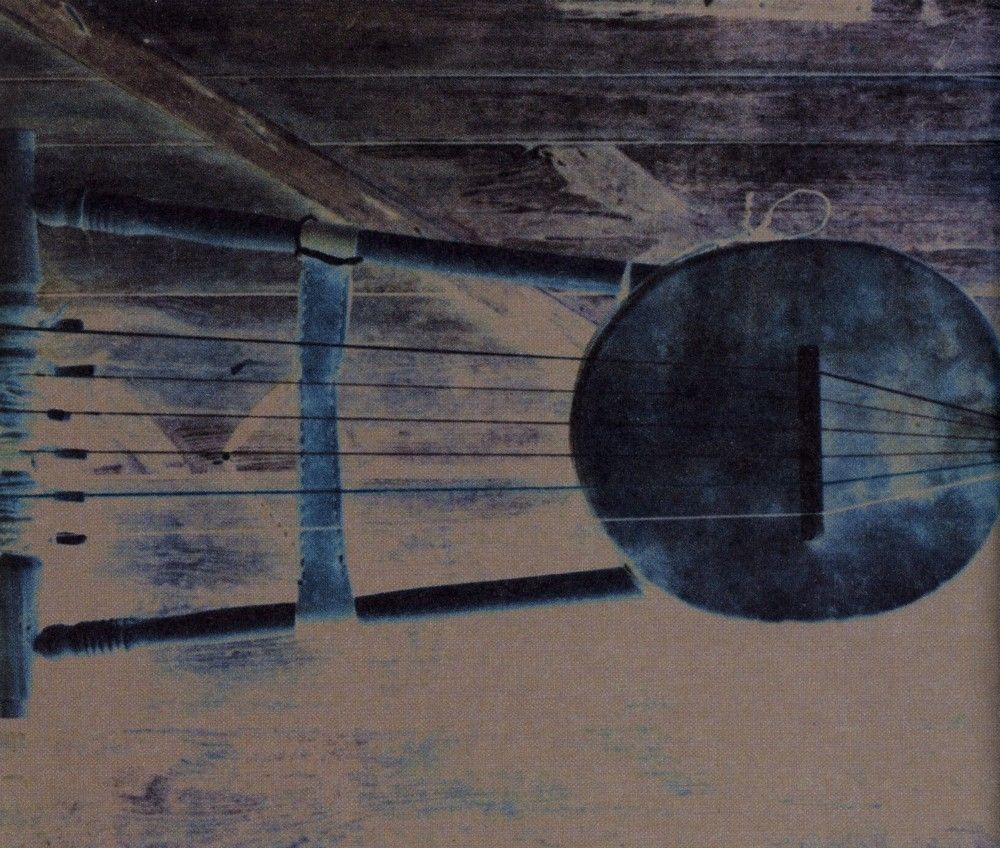

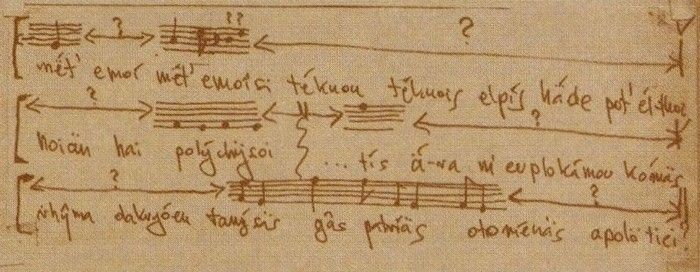

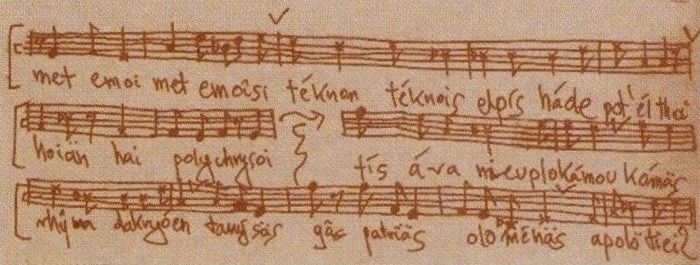

Oprócz steli Seikilosa mamy jeszcze dwa peany delfickie wyryte

na kamieniach. Cóż to jednak za pomysł, żeby nuty ryć w

kamieniu? Muzycy zapisywali swoje pomysły na papirusach.

Szczególnie dobrą śpiewkę przepisywano nieraz przez wiele

pokoleń Jak odczytywać dziś te dawne zapisy? Krzyczeć je, czy szeptać? Czy uwierzyć w jedną linię melodii zapisaną nad tekstem? Spójrzmy na rzeźby, mozaiki, ceramikę z epoki. Zachowało się mnóstwo scen z muzyką. Co widzimy? Muzyków grających na tzw aulosach — dwóch obojach-fletach równocześnie. Jeżeli ktoś gra na dwóch piszczałkach równocześnie to znaczy, że szuka wspólbrzmień. Tradycja gry na aulosie musiała prowadzić do najprostszej harmonii. Być może każda piszczałka prowadziła głos innej części chóru. Jeden muzyk grający na dwóch fletach to nie to samo, co dwóch grających równocześnie — każdy na swoim. To we współczesnej kulturze flet oznacza samotność. Ważna rzeczą było też dla mnie doświadczenie elementarnego rytmu, a więc usłyszenie z calą wyrazistością rytmiki mowy. Swoje próby zaczynałem od melorecytacji. Antyk skandował, bębnił, dzwonił rytmicznie. Prowadzący chóry mieli specjalnie skonstruowane trzaskające sandały. Tak zachowywali się muzycy. Nie siedzieli zgarbieni nad nutami. Widzimy ich w tanecznych gestach. Ich ciało żyje. Spotkałem wyjątkowych ludzi — grupę specjalistów od niekonwencjonalnych technik wokalnych, ponadto obeznanych ze śpiewem tradycyjnym, w którym naturalne brzmienie ludzkiego głosu jest oczywistością, bo też głosy aktorów Teatru Gardzienice są charakterystyczne, ekspresyjne, kolorowe. Ci ludzie potrafią szeptać i krzyczeć. Eksperymentują z barwą. Nie mają uprzedzeń. Kiedy Włodzimierz Staniewski otworzył w Gardzienicach szeroki projekt pracy i studiów nad antykiem, umożliwił mi realizację marzenia. Ale najpierw musiałem wyśpiewać im całą tę grecką muzykę. Spotykaliśmy się na próbach czytania muzyki antyku przez wiele miesięcy. Podczas takich spotkań naturalnym biegiem muzycznych zdarzeń wyłonili się soliści — Mariana Sadowska i Marcin Mrowca. Zaproponowali coś więcej niż indywidualny śpiew. Stworzyli zupełnie nową jakość. Nic dziwnego, że przejęli w teatrze odpowiedzialność za muzykę — jej brzmienie i formę. Jeszcze wcześniej pracowaliśmy w Anglii. Tam, po wyczerpujących warsztatach, które Gardzienice prowadziły dla aktorów Royal Shekespeare Company, siadaliśmy z Tomkiem Rodowiczem i usiłowaliśmy przesluchiwać zrekonstruowaną muzykę antycznej Grecji. Nigdy nam się to do końca nie udało. A jednak próba wywiedzenia muzyki ze strzępków ocalałych papirusów, okruchów kamieni nie dawała spokoju. Jeśli znalazła swą ostateczną, gardzienicką formę, to właśnie dzięki pierwotnemu wsparciu i entuzjazmowi Tomka Rodowicza. Po powrocie do Polski dosłownie przeczesywałem biblioteki. Książka Martina Westa Ancient Greek Music zjawiła się jak znak. Była dla nas światłem antyku, biblią neofity. W Gardzienicach kołysałem się, tupałem, śpiewałem, stukotałem — jednym słowem zachowywałem się dziwnie, a aktorzy notowali to jak chcieli, jak rozumieli. Śpiewałem w niezrozumiałym dla siebie i dla nich języku. Przywoływaliśmy melodie idiolektem. Ze szkicem melodii łączyłem bezsensowne sylaby, które zjawiały się jak organiczna oczywistość. Pojawiały się pierwsze impulsy muzycznego sensu. Z czasem te emocjonalne zawołania zostały zamienione na słowa rodem z Antyku. Pomagał mi Damian Kierek, lingwista, znawca starożytnej greki. Czasami próbowałem towarzyszyć Damianowi w jego zmaganiach nad rekonstrukcją, nad logicznym zintegrowaniem tekstu. Kiedyś przez całą noc przeszukiwał słowniki, by w końcu dopisać jeden brakujący wyraz. Po tej nocy zrozumiałem, że jesteśmy w takiej samej sytuacji. Dotknął nas przymus niepotrzebnego trudu. Wobec kogo staraliśmy się być uczciwi tworząc muzyczną wizję na użytek teatralnej sztuki? Nie wiem! Chciałem krzyczeć po dolinach, śpiewać w dwugłosach, bić w bębny z całej siły, obserwować jak żyje ciało. Na szczęście Grecy tańczyli poezję. Spiewali ją, a trzy nuty zapisane, to dwa kroki. Chciałem płakać, szeptać, wzdychać. Przykład? Eurypides, Ifigenia.  Do tego tekstu zachowało się kilka nut na pięciu postrzępionych kawałkach. Tylko drugi i piąty ma trochę smaku. W drugim ciekawe jest tarcie między dźwiękami a i b w zwrocie a d b d. W piątym fragmencie sugestywny jest skok e f przekraczający oktawę. W takim klimacie można tworzyć melodie o modlitewnym charakterze. Dalszym etapem pracy było poszukiwanie współbrzmień skalowłaściwych. Trzeba też było ustalić, gdzie tak skonstruowana melodia oddycha? Warto też uzupełnić lukę, miejsce przerwania papirusu ze słowami. Jaki jest efekt takich zabiegów, nie będę opisywał — można to usłyszeć w Met' emoi (22).  Pracowałem nad cząstkami. Wyławiałem to, co charakterystyczne i poszukiwałem ekspresji dramatycznej linii melodii. Wyszukiwałem zawołania tworząc z nich ostinatowe struktury, na których można było nadbudować melodie opowiadające. Oznaczałem ciszę licząc jej trwanie ściśle ustalonymi oddechami. Uczyłem tego innych przez żywy dźwięk, nie przez pismo. Włączyłem, acz delikatnie, specjalnie budowane instrumenty dające archaiczne brzmienie: ukośny flet z epoki ptolomejskiej, grające muszle, metalowe kastaniety (kymbala), jarzmową lirę, czy zaprojektowane przez Tomasza Rodowicza: monochord pitagorejski i samorodną harfę z dębu. Przywoływałem muzykę antyku. Nie uważam mojej pracy za rekonstrukcję. Rekonstrukcja jest tu po prostu niemożliwa. Nie twierdzę, że tak brzmiała muzyka antyku. Moja propozycja to muzyka komponowana znajdująca się na ścieżce Arche. Jest ona dążeniem, drogą ku przeszłości. Muzyka ta ma moc zespolenia zespołu w harmonii antycznej skali. Jest zintegrowana z tym, co mimo wszystko ocalało. Jest komponowana z całym szacunkiem dla muzycznego gestu — znaku przeszłości. MACIEJ RYCHŁY |

Apart

from the stela we have two more Delphic paeans written in stone. Why

the idea, however, to set notes in stone? Normally, musicians jotted

their ideas on papyri. A particularly good song would then be copied for

many generations. How should all these old remains be interpreted? Should we shout? Or whisper? Should we rely on the single melody line written above the words? Let's look at sculptures, mosaics, ceramic remains from that era. Numerous musical scenes have, in fact, been preserved. What do we see? Musicians play the so-called aulos — a double-reed oboe-flute. If a musician plays two reeds at the same time, he creates simultaneous combinations of sounds. The tradition of aulos performances led to first basic harmonies. Perhaps every reed led the voice of a different part of a choir. One musician playing two reeds is not the same as two players performing simultaneously, each on his own instrument. It is only in modern culture that the flute has become associated with solitude and detachment. It was also important for me to experience the elementary rhythm, that is, to hear most distinctly the rhythm of speech and diction. I began my own attempts by chanting, half-singing and half-speaking. Antiquity was full of chanting, drumming, rhythmic bell-ringing. Choir leaders wore specially constructed noise-making sandals. That's how musicians really behaved. They did not use to sit hunched over their scores. We see them flying in dance movements. Their entire bodies are alive with music. I have met some truly exceptional people, a group of specialists in unconventional vocal techniques, acquainted with traditional singing where the natural sound of a human voice is obvious, because the voices of Gardzienice's actors are characteristic, expressive, colourful. These people can whisper and shout. They experiment with timbre. They do not have prejudices. I sang all this music to the actors of the Gardzienice theatre. When Włodzimierz Staniewski started a wide project of work and studies on Antiquity in Gardzienice, he enabled me to fulfil my dream. At our meetings and rehearsals we had attempted to decipher the music of Antiquity. At the meetings soloists Mariana Sadowska and Marcin Mrowca, emerged in a natural way. They offered something more than individual singing. They created a completely new quality. No wonder that in the theatre they took over the responsibility for music, its sound and form. Earlier still we had been working in England. After our exhausting work (Gardzienice presented a series of workshops for the Royal Shakespeare Company) we would sit down with Tomasz Rodowicz to try and listen to tapes with the reconstructed music of ancient Greece. We never succeeded. And yet, we remained intrigued by the challenge of conceiving musical metaphors on the basis of preserved papyri fragments and bits of stone. The final Gardzienice product first originated in the support and enthusiasm of Tomasz Rodowicz. After my return to Poland I went through numerous library catalogues. Martin West's Ancient Greek Music appeared like a sign. For us, it became an illumination of ancient times, almost like a neophyte's Bible. Once in Gardzienice, I swayed, stomped, chanted, drummed — in other words, I behaved oddly, and the actors perceived and accepted this according to their own will and understanding. I sang in a language that neither I or they knew. Together, we were discovering the idiom of ancient melody. I linked my melodic draft with meaningless syllables that emerged as an organic necessity. The first impulses of the musical text had thus been generated; in time, these emotional invocations were replaced by words and phrases from ancient times. I was greatly helped by Damian Kierek, a linguist who specializes in ancient Greek. On occasions I tried to help him in his efforts to reconstruct and logically integrate the text. One time, he was leafing through dictionaries all night long to add one single missing word. After that night I understood that we were in the same situation. We were both affected by the pressures of unnecessary labour. We tried to remain as faithful as possible while creating the musical vision to be used in the theatre. Faithful to whom? I really am not able to answer that... I wanted to shout in valleys, chant in double-voice, drum with all my might, experience the living body. The Greeks, fortunately, danced their poetry. They sang it, too, and for every three recorded notes there were two dance steps. I wanted to cry... whisper... sigh... Example? Euripides, lphigenia. Only a few notes to this text have survived, in five torn scraps. Only the second and the fifth have some bite. In the second fragment there is an interesting tension between A and B in the phrase ADBD. The fifth piece contains an expressive step from E to F that exceeds the span of modern octave. This produces an environment suitable for creating worshipful melodies. During the next phase of my work I was trying to establish combinations of sounds that would be appropriate to the ancient scales. It was also necessary to ascertain in what places a melody, thus constructed, would breathe, and to restore the missing parts where the papyrus was torn. There is no need to describe the effects — they are here for all to listen to Met' emoi (22). I was working on small fragments, identifying their characteristic features and searching for the expression of dramatic melodic lines. I detected invocations, constructing repeated ostinato structures on which to build narrative melodies. I marked up silent breaks by counting strictly measured breaths. I taught others with a living sound, not a script. I have included, albeit subtly, especially constructed instruments that add to the archaic effect: a Pythagorean monochord and an oak harp, both assembled by Tomasz Rodowicz, as well as metal castanets, the ancient lyre, shell horns, flute (reconstruction from the times of Ptolemeus). I have recalled the music of Antiquity. I do not regard my work as reconstruction. Reconstruction as such is simply not possible. I am far from maintaining that the music of ancient times sounded like this. My proposal focuses on composed music that finds itself on the path of Arche — a music that is a desire for, and a way into, the past. This music has the power to unite the group's voices within the harmonies of an ancient scale. It is integrated with whatever has remained. It has been composed with the full respect for the musical gesture — sign of the past. MACIEJ RYCHŁY * The Polish text, in a folk dialect, means: I have nothing, I have nothing, and I care for nothing but that what I love were mine. | |