TOMASZ RODOWICZ

|

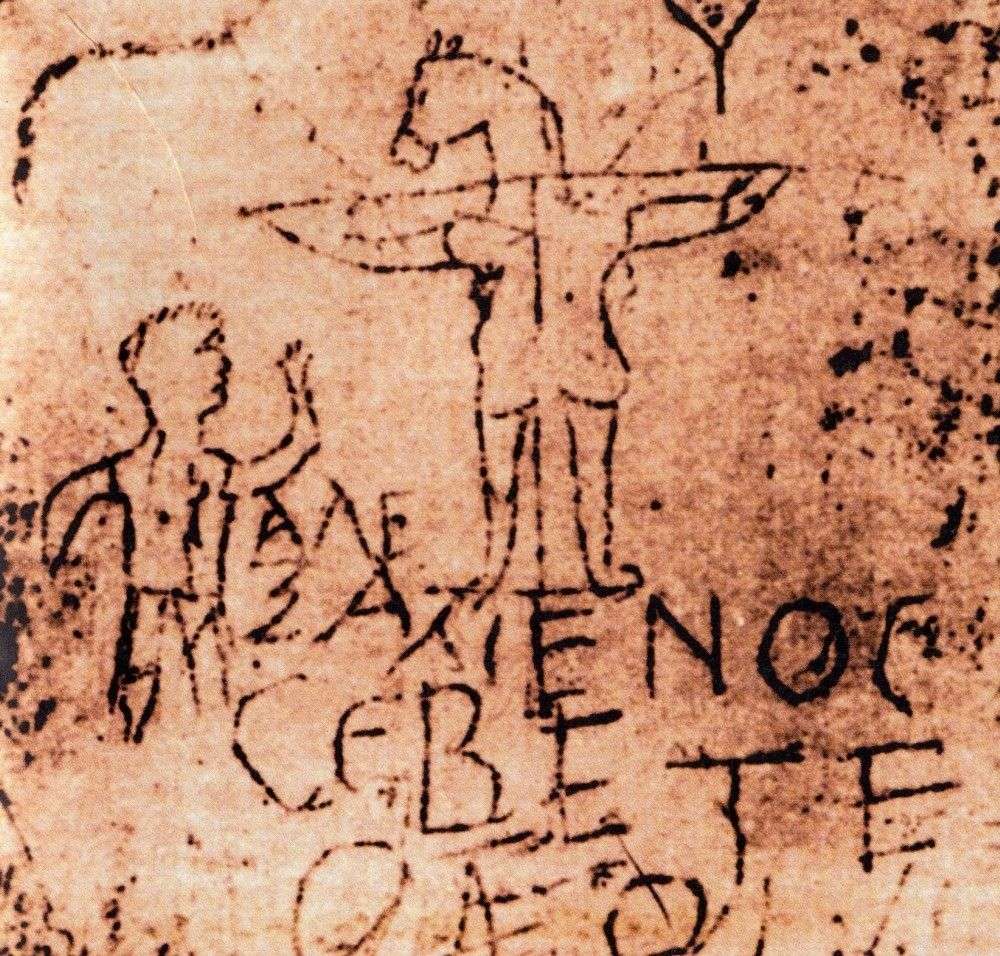

Praca nad Metamorfozami biegła równolegle dwoma torami, które przez wiele miesięcy nie przecinały się. Pierwszy, prowadzony przez Włodzimierza Staniewskiego dotyczył Apulejusza, Platona, szukania odniesień do naszych Wypraw, wspólnych studiów nad ikonografią antyczna i tworzenia nowego treningu aktorskiego. Drugi, prowadzony przez Macieja Rychłego, był próbą wejścia w świat muzyki antycznej Grecji. Silą rzeczy tutaj będzie o tym drugim. Gdy Maciej Rychły po raz pierwszy próbował wyśpiewać nam swoje greckie hymny patrzyliśmy na siebie zaniepokojeni. Oszalał! — myśleliśmy. — Co to za muzyka? Tych melodii, w takich rytmach nie da się zaśpiewać! A jednak okazało się, że tak konsekwentne odczytywanie starożytnych zapisów rytmami nieparzystymi jest największą wartością jego propozycji. Pragnął, żebyśmy muzykę antyku odczytali przez rytmy Bałkanów i Peloponezu. Pokazał, jak tkwią one w wewnętrznej strukturze antycznej poezji. Śpiewając hymny greckie w pięcio, siedmio, dziewięcio czy dziesięciomiarze (3+3+2+2), poczuliśmy we własnych ciałach, że rytmy te mają moc kół zamachowych. Ostatnia część taktu każdej frazy stawała się jednocześnie początkiem następnej. Nie było wyhamowań, pieśń była jak toczące się koło! W odróżnieniu jednak od tradycyjnej muzyki bałkańskiej, gdzie akcenty są na ogół stałe, a puls łatwo wyczuwalny, w naszych hymnach akcent stawał się ruchomy i podążał za słowem, a ukryte i nakładające się na siebie rytmy tworzyły własne wewnętrzne napięcia i dramaturgię. Nie da się przy nich zasnąć! Początki były jednak trudne. Pracowaliśmy nad maleńkimi cząstkami każdej pieśni po wiele godzin. Barwę i siłę brzmienia, żywość tego, co Maciej zrekonstruował i wydobył z ocalałych szczątków muzyki, mógł sprawdzić dopiero na żywym organizmie zespołu aktorskiego, czyli na nas. W trakcie pracy często dopisywał lub zmieniał całe sekwencje, również w wyniku współpracy z reżyserem. Narzucił nam of ostrą dyscyplinę wykonawcza. Na przykład to, co jest naturalnym, indywidualnym sposobem nabierania powietrza przez śpiewaka, warunkowanym przez pojemność płuc i przeponę, tutaj miało stać się integralną częścią muzyki. Nie było miejsca na prywatne oddychanie. Wdech i wydech uzyskał taką sama wartość muzyczną jak każdy inny dźwięk pieśni. Najlepiej można to usłyszeć w utworach Hode Galatan Ares barbaros (12) i Chrysea Phorminx (21). Oprócz tego Maciej zrobił jeszcze dwa niezwykle trudne założenia. Pierwsze nawiązywało do podstawowej zasady pracy w naszym teatrze, stosowanej od początku istnienia grupy: śpiew i muzyka uzyskują zupełnie nową wartość o ile rodzą się ze współbrzmienia, z wzajemności, z odnoszenia do siebie nawzajem każdej frazy, każdej cząstki pieśni. Wtedy pieśń nie jest sumą poszczególnych głosów. Zyskuje energię. Jest subtelniejsza i wielokrotnie mocniejsza. Tworzy się nowa jakość obecności. To brzmi być może zbyt metaforycznie, ale jest do sprawdzenia na miejscu u nas, w Gardzienicach. Można to wyśpiewać. W praktyce realizacja założenia wprowadzonego przez Macieja oznaczała pracę całego zespołu, prawie zawsze razem, nad wszystkimi wątkami melodycznymi i rytmicznymi naraz. Ogromnie to wydłużało próby. Były one czasami niezwykle wyczerpujące. Pozwalało jednak zorientować się po uzyskaniu pełnego współbrzmienia, właściwego pulsu, tempa i rytmu danej pieśni, czy ta wersja rekonstrukcji jest żywa czy martwa, organiczna czy sztuczna, akademicka czy rockowa, grecka czy huculska, co może wnieść i co budować w spektaklu. Drugim założeniem Macieja było zrezygnowanie z tradycyjnej notacji muzycznej w trakcie przyswajania przez aktorów materiału muzycznego. Chociaż sam posługiwał się precyzyjnie opracowaną przez siebie partyturą, nie pozwalał do niej zaglądać. Zaproponował, żeby każdy wypracował swój własny graficzny zapis rytmu i melodii do śpiewanego greckiego tekstu. Chciał, abyśmy odwołali się do własnej wyobraźni i użyli takiej grafiki, takich znaków czy symboli, które najłatwiej i najmocniej wpiszą się w pamięć i jednocześnie odniosą się do innych głosów i całej struktury pieśni. I rzeczywiście, po początkowej bezradności, a nawet próbach buntu, okazało się, że najszybciej przywoływane jest z pamięci to, co samemu się nakreśliło. Powstało kilka całkowicie różniących się od siebie zapisów tej samej muzyki. Po kilkudziesięciu próbach od wystukiwania rytmów i przesuwaniu palcami po jambach i heksametrach greckich peanów, nasze autorskie notacje wyglądały jak archaiczne manuskrypty. Każdą muzykę, każdą pieśń, a na pewno tę, której nie otrzymało się w przekazie bezpośrednim, trzeba wystawić na wiele prób, aby traktować jak własną. Trzeba ją wielokrotnie na różne sposoby wyśpiewać — od patosu do ironii, od radości do histerii. Wszystko po to, by zbudzić jej ukrytą energię lub obnażyć pustkę. Kiedy wreszcie pieśń zostaje oswojona i wszystkie elementy antycznej mozaiki zaczynają układać się w jedną całość, można usłyszeć jej przestanie. Można usłyszeć, któremu bogu jest to śpiewane — Dionizosowi czy Apollinowi, jakiej przemianie z Metamorfoz Apulejusza może towarzyszyć. Zaraz potem wzniosła Grecja musiała przejrzeć się w naszej błotnistej, wiejskiej rzeczywistości, w naszych Wyprawach, w spotkaniach z ludźmi, w naszym codziennym życiu. Pamiętam, jak przez szereg dni wprowadzaliśmy w lamentacje Eurypidesa szczekania gardzienickich psów. Każdy dostał od reżysera zadanie aktorsko-muzyczne, by w precyzyjną, polirytmiczną strukturę jedynego ocalałego fragmentu muzycznego Orestei wpisać charakterystyczne szczekanie psa swojego najbliższego sąsiada we wsi. Zadawaliśmy sobie też pytanie: lak dwa i pit tysiąca lat temu w Atenach kilkudziesięcioosobowe chóry przygotowywały dytyramby i całe tragedie Ajschylosa, Sofoklesa czy Eurypidesa na konkursy Wielkich Dionizji? Pamiętajmy, że wtedy tragedie były najczęściej śpiewane i tańczone! W Gardzienicach było nas zaledwie 10 osób, a pracowaliśmy nad strzępami kilkudziesięciu utworów. Pamiętam nocne telefony do współpracujących z nami filologów: prof. Jerzego Danielewicza, dra Lecha Trzcionkowskiego czy Damiana Kierka. Budziliśmy ich swoimi wątpliwościami: Brakuje nam słowa w drugim wersie i jednej sylaby w czwartym. Co znaczy ...toude topou...? Z trzech kawałków skorup trzeba było zrobić całą wazę i to taką, żeby można było pić z niej wino. Z teatru antycznego ocalały tylko słowa. Teatr ten bez muzyki, tańca, śpiewu i ruchu przywołuje na myśl zastygłe greckie kolumny i rzeźby w muzeach Aten, Rzymu czy Berlina. Zeszła z nich pokrywająca je przed wiekami bajecznie kolorowa farba. Gdy podziwiali je starożytni Grecy, wszystkie były barwne jak posągi Azteków, jak boginie indyjskie czy kolorowe ptaki na wiejskich jarmarkach. W Gardzienicach próbujemy pomalować rzeźby, ożywić skamieniałe gesty, odnaleźć muzykę antycznej poezji. Namawiamy się z Maćkiem Rychłym na odczytywanie kolejnych papirusów. A Włodzimierz Staniewski zapowiada następny duży projekt teatralny związany z antykiem. Wszyscy mamy świadomość, że to początek drogi. TOMASZ RODOWICZ |

The work on Metamorphoses proceeded on two levels which were independent of each other for many months.

The first level conducted by Włodzimierz Staniewskie was connected with

Apuleius and Plato, looking for references to our Expeditions, studies

of ancient iconography and the creation of new actors' techniques. The second level conducted by Maciej Rychły was an attempt to enter the world of ancient Greek music. By the force of events the latter level will be discussed here. When Maciej Rychły tried to sing to us his Greek hymns we looked at one another anxiously. He is crazy! — we thought — What kind of music is that? Those songs can't be sung in these rhythms. However, it turned out quickly that consistent reading of ancient scripts through rhythms is the greatest value of his offer. He wanted us to read ancient music through the rhythms of the Balkans or Peloponnesian Penisula. He showed how they reside in the inner structure of ancient poetry. Singing Greek hymns like Balkan ones (3+3+2+2) we felt in our bodies that these rhythms have the power of flywheels. The last part of the bar of each phrase was at the same time the beginning of another phrase. The song was like a rolling wheel! However, as opposed to traditional Balkan music where the emphases are usually constant and the pulse is felt easily, in our hymns the emphasis became movable and followed words while hidden and superimposed on one another rhythms formed their own inner tension and dramaturgy. One cannot fall asleep listening to them. Nevertheless, the beginnings were difficult. We were working many hours on small pieces of every song. The timbre of Maciej's reconstructions had to be checked on a living organism of actors, on us. During work he frequently added or changed whole sequences. This happened also due to the collaboration with the director. He imposed hard executive discipline on us. For instance the natural, individual way of taking a breath determined by the capacity of lungs and one's diaphragm became here an integral part of music. There was no place for private breathing. Inhalation and exhalation had the same musical value as any other sound in a song. It is best illustrated in Hode Galatan Ares barbaros (12) and Chrysea Phorminx (21), Apart from that Maciej also made two extremely difficult assumptions. The first referred to the basic rule of work in our theatre, practiced from the beginning of Gardzienice: singing and music get completely new value if they arise from sound combination, reciprocation, from referring every phrase, every part of a song to one another. Then the song is a sum of individual voices. It gets energy. It is more subtle and multiply stronger. A new quality of presence is created. This may sound too metaphorical but one can check it here in Gardzienice. One can sing it. In practice the completion of the assumption made by Maciej meant the work of the whole group, almost always together, the work on the melodic and rhythmical plots simultaneously. It prolonged the rehearsals immensely. Sometimes they were incredibly tiring but after obtaining the full sound combination the right pulse, tempo and rhythm of a given song we could hear whether this version of the reconstruction is alive or dead, organic or artificial, Greek or Hucul, academic or rock and what it can bring to and build in the performance. The second assumption made by Maciej was the resignation from the traditional musical notation during the time of absorbing the musical material by the actors. Although he was able to use the score prepared by himself perfectly, he didn't let us look at it. He suggested that every one of us should work out his or her own graphic notation of the rhythm and melody to the sung Greek text. He wanted us to refer to our imagination and use such notation, such signs or symbols which would engrave in everybody's memory most easily and strongly and at the same time they would relate to the voices of other actors and the whole structure of a song. Indeed, after initial helplessness or even attempts of a revolt it turned out that most quickly one recalls from his or her memory what he or she placed there. There were a few completely different notations of the same music. After numerous rehearsals including clattering of the rhythms, moving fingers on iambuses and hexameters of Greek paeans our author notations looked like archaic manuscripts. Every type of music , every song and surely the one which we didn't get directly has to be practiced many times in order to treat this song or music as our own. It has to be sung in many different ways — from pathos to irony, from joy to hysteria. One has to do that to wake up its hidden energy or expose its emptiness. When finally the song is tame and all the elements of the ancient mosaic form one whole, then it can be heard for which god the song is sung (whether for Dionysus or Apollo), for which hero, which transformation from Metamorphoses by Apuleius this song can accompany. Immediately afterwards lofty Greece had to look at itself in our muddy, rural reality, in our Gatherings, meetings with people, in everyday life. I remember that we inserted the barking of the dogs from Gardzienice in Euripides's lamentations. Every actor got a musical task from the director to write the characteristic barking of his or her closest neighbor's dog into the polirythmical structure of the only existing musical passage from Orestea. We asked ourselves a question: how 2500 years ago in Athens a few dozen people choirs prepared dithyrambs and tragedies of Sophocles, Aeschylus or Euripides for the Great Dionysian competition. One has to keep in mind that at that time tragedies were mostly sung and danced! There were only ten of us in Gardzienice but we were working on the shreds of a few dozen compositions. I remember phone calls at night to collaborating linguists: prof. Jerzy Danielewicz, dr Lech Trzcionkowski and Damian Kierek. We woke them up with our questions: We don't have a word in the second verse and a syllable in the fourth line. What does ...toude topou... mean? Having three separate pieces we had to make a whole vase, such a vase that wine could be drunk out of it. Only words remain after ancient theatre. This theatre without music, dance, singing and movement is like Greek columns and sculptures in the museums of Athens, Rome or Berlin. They lack the colorful paint which disappeared centuries ago. When these sculptures were admired by the ancient Greek they were colorful like Aztecs' statues, Indian goddesses or colorful birds at the country fairs. In Gardzienice we try to paint the statues, to revive frozen gestures, to find the music of ancient poetry. Together with Maciej Rychly we plan to start working on other papyri. And Włodzimierz Staniewski has announced that he is going to prepare a new theatrical project connected with Antiquity. We all are aware that this is the beginning of the road. TOMASZ RODOWICZ |

WŁODZIMIERZ STANIEWSKI

|

Muzyka jest początkiem i istotą każdej rzeczy, która powołuję

w naszym teatrze, żywą energia, silą napędową. Ona teatralnej materii

nadaje dynamikę, wnosi radość. Każda próbę zaczynam od muzyki. W

muzyce szukam wskazań do rozwiązywania zadań aktorskich. Rzec by można:

muzyka jest moim współreżyserem. Niegdyś, w połowie lat siedemdziesiątych, na początku Gardzienic, tradycyjną kulturę i wieś nazwałem nowym naturalnym środowiskiem teatru. W trakcie pracy nad Gargantua i Pantagruelem czy Awwakumem, odbyliśmy dziesiątki Wypraw na wieś, podczas których wszystkie elementy spektaklu konfrontowaliśmy z rdzennym śpiewem i gestem. Proces ten służył naturalizacji spektaklu. Wtedy stawką moją był mityczny wóz z sianem, na którym Antyk uciekając przed zagładą wywoził — jak wierzę — tajemnice swoich misteriów i krył je wśród ludu. Podczas pracy nad materiałem muzycznym do Metamorfoz dość radykalnie zmieniłem naszą filozofię wzajemności teatru i muzyki. Wiemy, że Antyk był rozśpiewany, roztańczony, ale z tamtej muzyki pozostały jedynie ślady, zapisane na papirusach lub wyryte na kamieniach. Po raz pierwszy więc musieliśmy uczyć się nie od ludzi, a od kamieni. Szczęśliwie nasze drogi skrzyżowały się z drogami Macieja Rychłego. Rychły przestudiował zabytki muzyki, która powstawała na terenie Grecji między V w. p.n.e. a II w. n.e. Ożywił istniejące zapisy uzupełniając brakujące fragmenty. Zależało mi, aby w rekonstrukcji szukał analogii do ludowej muzyki słowiańszczyzny. Rezultaty jego pracy były niezwykle, choć trudne dla aktorów, którzy mieli tę muzykę odczyniać. Okazało się bowiem, że wyśpiewanie struktur wziętych z kamieni pochłania tyle uwagi, iż praktyczne uniemożliwia wykonywanie bardziej skomplikowanych działań aktorskich. We wcześniejszej pracy, z jakiejkolwiek kultury nie brałoby się pieśni, natychmiast czuło się i słyszało wpisaną w nią dramaturgię. Zawsze widziałem oczyma wyobraźni, ku jakim sytuacjom i działaniom prowadzi. Tutaj kamienna cisza. Dla potrzeb spektaklu musiałem więc modyfikować te wzięte z kamienia struktury, proponować tempa, przekładać wewnętrzne akcenty w taki sposób, żeby pieśń mogla nieść ruch i gest aktorski. Zależało mi zwłaszcza na pewnej jakości, która od czasów Awwakuma nazywam antyfonalnością obecności scenicznej. Antyfona to śpiewanie w odpowiedzi. Aktor prowadzi określony wątek (ruchowo-melodyczny), jak w fudze, a drugi aktor musi pozostawać w odpowiedzi z tamtym. Linie życia pieśni spektaklu mają oddawać klimat księgi Metamorfozy albo Złoty Osioł — kultowej już od momentu jej napisania w II w n.e. Dla późniejszych pokoleń dzieło to było wielką zagadka i niewyczerpalnym źródłem inspiracji. Dziś jest zdumiewająco aktualne w widzeniu świata, w ocenie marności i przemienności ludzkiego losu, a przede wszystkim — w apoteozie misteriów, ukazujących drogę do transcendencji, do duchowości. Księgę napisał Apulejusz z Madaury w czasach wielkiego przełomu, kiedy dawni bogowie — Dionizos i Apollo — zabierali się do odejścia, a na scenę wkraczał nowy Bóg Chrystus. Proponujemy więc śpiewy w tonacjach starożytnych, ale glosami współczesnymi. Dynamiki, tempa i rytmu szukaliśmy z Maćkiem we współcześnie żywych tradycjach rdzennych. Kto wie, może właśnie dzięki temu jesteśmy bliżej Ducha Tamtej Epoki? Antycznej muzyki nikt nie jest już w stanie wiernie odtworzyć. Jak zawsze w takich wyprawach, trzeba iść za intuicją. WŁODZIMIERZ STANIEWSKI |

Music is at the

origin and core of everything that I generate in our theatre, it is the

primeval source of everything, a vital energy and life-force. It

gives a fundamental dynamics to the entire structure of theatrical

material and enhances it with joy and delight. I begin every rehearsal

with music. In it, I seek a direction for artistic action. In the end,

music acts as my co-director. Some time ago, in the middle of the 70s, at the beginning of Gardzienice, I termed the traditional cultural connection a new and natural theatrical environment. In the course of the work on Gargantua and Pantagruel or The Life of Protopope Avvakum, the Gardzienice group paid dozens of Expeditions to villages and small communities, during which we related all elements of the performance to the living tradition of indigenous singing. This process served to naturalize the performance. What I had at stake then was a mythical hay cart on which Antiquity, while fleeing from disaster was carrying away valuables of its misteries to hide them among the people. In the course of our work on the Metamorphoses I was forced to change, at times quite radically, our philosophy of mutuality between theatre and music. We know today that music permeated the fabric of life in ancient times, that Antiquity was all-singing and all-dancing — but, in most cases, only traces of the actual music of ancient Greece have been preserved, written on papyri or set in stone. For the first time, then, we had to learn our music not from people but from stones. Fortunately, though, our paths crossed at that time with those of Maciej Rychły. He thoroughly examined the remains of music that had been created in the Greek territory between the fifth [century] B.C. and the second century A.D. He breathed life into existing notation and reconstructed the missing fragments. It was important to me that, in his reconstruction attempts, Rychły maintained the connection with the living folk music. The results were truly amazing and, at the same time, presented great challenges for actors cast to perform this music in my production. Paradoxically, though, the mastering of the music became an overriding passion and ambition of the group. It transpired, however, that the performance of those stone-derived structures was so attention- and energy-consuming that it seriously jeopardized all the more complex theatrical actions. In our previous work, no matter what musical tradition we had used, the music immediately imparted its intrinsic drama, so that it could be both felt and heard. In my imagination, I had always intuited the movements that would follow the music. Here, however, this was not the case. Consequently, for our work these stone-derived structures had to be modified and transposed into new tempos and rhythms, with internal accents positioned so as to inspire and enhance the actors' movements and gestures as well as the mode of dialogue. I was particularly keen to evoke a particular quality which I have called, ever since the production of The Life of Protopope Avvakum, the antiphonality of theatrical presence. Antiphony involves the exchange of sung responses. As in the fugue, one actor leads a motif (a specific movement and tune or movement and music) and another needs to remain in response to that with his or her own motif. The song lines remain related in their climates meaning to the book that gave its philosophical intent for the performance. Apuleius from Madaura wrote his Metamorphoses in the times of a great transformation, when the old gods of the Mediterranean circle, Apollo and Dionysus, were retreating, and the new one — Christ — was taking over. We have here proposed a way of performing the ancient tunes according to ancient scales but in modern voices. We were looking with Maciej for the dynamics, tempo and rhythm in contemporary alive indigenous traditions. But who knows — perhaps what we have done still manages to reflect the Zeitgeist of that long-gone era? It is not possible, these days, to reconstruct the full ancient rhythm and idiom. We can only follow our intuition. WŁODZIMIERZ STANIEWSKI |