DARIUSZ KOSIŃSKI

|

Ośrodek Praktyk Teatralnych Gardzienice został formalnie zarejestrowany

w styczniu 1978 r. w Lublinie, ale na Wyprawę, w czasie której

prezentowano pierwszy spektakl zespołu, jego czionkowie wyruszyli w

październiku roku poprzedniego.

Jeszcze wcześniej, w lipcowy wieczór 1977 r., Włodzimierz

Staniewski po raz pierwszy przyjechał do Gardzienic — małej wsi

na wschodzie Polski, 32 km od Lublina. Bardzo szybko mało znana wioska

stata się jednym z najważniejszych miejsc na mapie polskiego teatru. Teatr stworzył przedstawienia: Spektakl wieczorny, Gusta, Żywot protopopa Awwakuma, Carmina Burana i Metamorfozy oraz wielogodzinny projekt Kosmos Gardzienic, będący twórczym połączeniem wątków trzech ostatnich spektakli z pokazem pracy aktorskiej, projekcją zapisów filmowych i prezentacją dokumentacji dotyczącej działalności grupy. Wielowątkowa praca nad każdym spektaklem trwa kilka lat. W pierwszym przedstawieniu z 1977 roku wykorzystano fragmenty Gargantui i Pantagruela Francoisa Rabelais'go oraz innych dziel (m.in. cz. Il Dziadów Adama Mickiewicza), a także tradycyjne pieśni i melodie, które składały się na szereg sekwencji o charakterze etiud. Tą z założenia płynną konstrukcją rządził żywioł muzyki towarzyszącej wszystkim działaniom. Całości patronował Michaił Bachtin ze swoją koncepcją karnawałowego odczucia świata i filozofią śmiechu. Spektakl wieczorny stanowił integralną część Wypraw, które w pierwszych latach działalności zespół podejmował regularnie co miesiąc. Byty to wędrówki po odległych wsiach w poszukiwaniu śladów tradycyjnej kultury, a zarazem kontaktu z publicznościa nieuprzedzoną, nie wyuczoną właściwego sposobu reagowania. Wyprawy, kontynuowane po dzień dzisiejszy, oparte są na zasadach wzajemności, swoistej kulturowej wymiany. Gardzienice przywożą swoje przedstawienia, pieśni, tańce i ofiarują je społeczności wsi w nadziei, że w zamian otrzymają dawne melodie, zapomniane już niemal słowa, zwyczaje, gesty. Ta wymiana odbywa się w czasie spotkań, które Staniewski nazywa Zgromadzeniami i w których widzi zjawisko przedteatralne — posiadające swoją dramaturgię spotkanie dwóch ludzkich grup. Wielokrotnie podkreślano znaczenie Wypraw i Zgromadzeń dla ocalania zanikających tradycji. Pierwszą próba pełniejszej wypowiedzi we własnym języku teatralnym byt następny spektakl — Gusła wg II części Dziadów Mickiewicza (1981 r.). Mickiewicz, jego poezja, osobowość, stosunek do tradycji ludowej, muzyki, teatru są w wypowiedziach Staniewskiego i działaniach Gardzienic obecne niemal od początku. Gusła w sposób naturalny wyrastały z tych związków, potwierdzając je przy tym w sposób o wiele głębszy, niż zwykła inscenizacja dramatu czy jego części. Zasadnicza materię przedstawienia stanowiły, tak jak u Mickiewicza, śpiewy (...) obrzędowe, gusła i inkantacje (...) po większej części wiernie, a niekiedy dosłownie z gminnej poezji wzięte. W niezwykle zagęszczonej strukturze fragmenty mickiewiczowskiego poematu wtopiły się w ekstatyczny śpiew i ruch. W Gusłach obecne były, już niemal w pełni rozwinięte, podstawowe cechy teatralnego stylu zespole: budowanie spektaklu w oparciu o strukturę muzyczną, świadome zderzanie przeciwieństw, ekstatyczność gry aktorskiej i oszałamiająca intensywność środków wyrazu. Prawdziwym wydarzeniem był Żywot protopopa Awwakuma (1982 r.). Przedstawienie oparto na autobiografii Awwakuma Pietrowicza, rosyjskiego popa, XVII-wiecznego ideologa staroobrzędowców, spalonego na stosie. W opowieści Awwakuma Staniewski znalazł material, który stal się punktem wyjścia dla ukazania pełnej sprzeczności duszy Euroazjaty. Podobnie jak w przypadku Guseł przedstawienie nie odwzorowywało oryginału, nie podążalo za jego fabułą. Istotę muzycznej tkanki Awwakuma stanowiły prawosławne śpiewy cerkiewne i ludowe pieśni zebrane przez zespól we wsiach wschodniej Polski. Gesty i postawy aktorzy wypracowali analizując m.in. ikony i sposób poruszania się kaplanów i wiernych prawosławia. Mimo kłopotów z egzegezą nikt właściwie nie miał wątpliwości, że Awwakum to teatralne arcydzieło, a Gardzienice zasługują na zaliczenie do grona mistrzów współczesnego teatru. Carmina Burana (1990 r.), przyjmowana była już jako dzieło dojrzałych twórców, dysponujących własnym charakterem pisma, własną wizją świata i człowieka. Przedstawienie, grane do dziś, powstało z dwóch wzajemnie uzupełniających się źródeł: słynnego zbioru średniowiecznych pieśni przechowywanych w bawarskim opactwie Benediktbeuren, a wykorzystanych przez Carla Orffa w jego świeckim oratorium, oraz historii miłości Tristana i Izoldy. Carmina Burana — monografia milości, jak mówi o spektaklu Staniewski — jest dziełem wstrząsającym w swym prostym i szlachetnym pięknie.

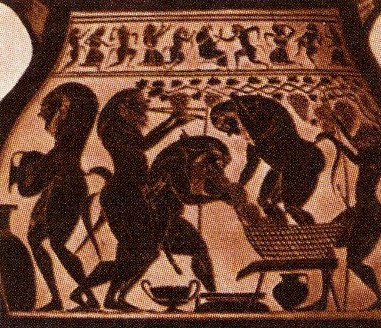

Przedstawienia Gardzienic nie mają premier, ponieważ nigdy nie osiągają takiego punktu, w którym mona powiedzieć, że są gotowe, skończone (me znaczy to, broń Boże, ze brak im struktury, lub że są improwizowane). Ich kształty, odcienie, brzmienia zmieniają się wraz z tworzącymi je ludźmi, wraz z czasem, w którym żyją. W pewnym momencie umierają, dając zarazem życie nowemu teatralnemu utworowi. Tak właśnie w ostatnich latach powoli odchodzi w przeszłość Carmina Burana i rodził się następny spektakl — Metamorfozy, esej teatralny według Apulejusza (1996 r.). Metamorfozy to fascynująca próba przywrócenia do życia muzyki starożytnej Grecji. To niezwykle piękna podróż do źródeł teatru. Owocem tej wyprawy jest nie tylko przedstawienie, ale i płyta. W przedstawieniach Gardzienic nie ma tradycyjnie pojmowanej, linearnej fabuły, wiodącej przez ciąg wydarzeń ku kulminacji i rozwiązaniu. Wydarzenia, słowa, emocje przeplatają się i przenikają, nigdy jednak nie wpadają w chaos. Podstawą panującego między nimi ładu jest muzyka, a właściwie, używając bardziej precyzyjnego terminu Staniewskiego, muzyczność. Swoiste brzmienia i rytmy właściwe każdemu aktorowi, każdej sytuacji, każdemu działaniu łączone są w oparciu o zasady kompozycyjne wywiedzione z muzyki. Muzyczność zastępuje dyskurs słowny. Do spektakli tego teatru najlepiej podejść jak do zjawiska przyrody, jak do mijanego w wędrówce krajobrazu. Przyroda nie przynosi morału, pouczenia, lekcji, a jednak nie można powiedzieć, że spotkanie z nią nie pozostawia głębokiego śladu, że nie wywołuje w nas zmian. Przyrody nie da się odczytać. Można ja za to uczynić częścią własnego doświadczenia. Podobnie jest z utworami Gardzienic. Staniewskiemu udała się rzecz niespotykana, a śniona przez wielu — doprowadzenie do tego, że widzowie stają się uczestnikami tworzonego wydarzenia, choć nie sa jego sprawcami. Praca nad poszczególnymi utworami teatralnymi to nie wszystko, co pochłania artystów Gardzienic. Mnóstwo czasu i energii poświęcono odbudowie i przywróceniu do życia siedziby teatru — oficyny XVII-wiecznego pałacu, ożywieniu starego parku. Włodzimierz Staniewski snuje plany przekształcenia Gardzienic w wielokulturową wioskę, miejsce twórczych spotkań ludzi wywodzących się z różnych tradycji. I choć projekt ten wciąż pozostaje w sferze marzeń, to podobne spotkania już się tam odbywają, także w formie międzynarodowych konferencji. Wiele wysiłku włożono w Wyprawy artystyczno-badawcze zespołu. Artyści na całym niemal świecie szukali potwierdzenia swej wiary w teatr. Podróże te często łączono z pracami warsztatowymi, z prezentacją gardzienickich metod treningu (m.in. współpraca z Royal Shakespeare Company). Zespół niemal od początku prowadzi też działalność edukacyjną, kształcąc grupy młodzieży, prowadząc w swojej siedzibie staże i warsztaty teatralne. W 1997 r. praca ta przyjęła instytucjonalna formę Akademii Praktyk Teatralnych. Dla Staniewskiego teatr z ducha muzyki ma ogromną wartość — pozwala dopuścić do gloso całość ludzkiego doświadczenia. Tworzony przez niego teatr to świątynia życia widzianego w całej pełni. le to przede wszystkim w pracach teatralnych widać trud budowania dzieła, które objąć ma wszystkie przejawy życia i na podobieństwo harmonia mundi łączyłoby we współbrzmieniu przeciwieństwa. Być może wtaśnie taki sens mają zagadkowe słowa Staniewskiego: Ja szukam w muzyce Zbawienia. Właściwie w Formie Teatralnej szukam Zbawienia. Przez Zbawienie rozumiem Stan Twórczego Skupienia, który moge osiągnąć tylko przez stworzenie formy, odnoszącej pierwiastki twórcze do innych światów. DARIUSZ KOSIŃSKI |

The Gardzienice Center for Theater

Practices was formally registered in January 1978 in Lublin, but its

members embarked on the Road Trip, during which the ensemble's first

show was presented, in October of the preceding year. Earlier

still, Włodzimierz Staniewski visited for the first time Gardzienice — a

little village outside Lublin. Very quickly a little known village

became one of the most important places on the map of Polish theatre. The theatre created five performances: The Evening Performance, Sorcery, The Life of Protopope Avvakum, Carmina Burana, Metamorphoses and a project Gardzienice's Cosmos which lasts many hours and which is an artistic combination of the plots from the latter three performances. It also consists of films connected with the activities of the theatre and the presentation of actors' work. The work on every performance lasts a few years. In the first performance from 1977 the passages from Gargantua and Pantagruel by F. Rabelais and other works (e.g. Part III of A. Mickiewicz's Dziady) were used as well as traditional melodies and songs which were formed into a number of étude-like sequences. This smooth construction was governed by the element of music accompanying all the actions. Michail Bachtin with his conception of the carnival-like perception of the world and the philosophy of laughter patronized the whole project. The Evening Performance is an integral part of the Trips which in the first years of the theatre's activities took place regularly every month. The actors of Gardzienice wandered through distant villages seeking traces of traditional culture, as well as contact with a public devoid of prejudices, not taught the right — in other words, in a certain way programmed — way to respond. The road trips, continued to this day, are based on principles of unique cultural exchange — Gardzienice has brought its presentations, songs and dances, and offered them to village society in the hope that it would receive in return ancient melodies, already nearly-forgotten words, gestures. This exchanges takes place in the course of meetings which Staniewski calls Gatherings, in which he sees a pre — theatrical phenomenon — a meeting of two groups of people, having its own dramaturgy. The importance of the Trips and Gatherings to save the disappearing traditions has been stressed many times. The first attempt at full expression in their own theatrical language was Sorcery, according to Part II of A. Mickiewicz's Dziady (1981). Mickiewicz, his poetry, personality, relationship to folk tradition, music and theater, have been present in Staniewski's statements and Gardzienice's activities almost from the beginning. Sorcery grew in a natural manner out of those relationships, confirming them at the same time in a manner much deeper than a normal staging of a drama or part thereof. The basic material of the presentation, just as in Mickiewicz's work, were ritual (...) songs sorcery and incantations (...) in large measure faithfully, and sometimes literally taken from communal poetry. In the unusually condensed structure of this presentation, lasting about 20 minutes, fragments of Mickiewicz's poem appeared in a completely changed context, melted into the ecstatic singing and movement of the group. In Sorcery there were present, already nearly fully developed, basic traits of Staniewski's theatrical style: construction of a show based on a musical structure, conscious confrontation of opposites, ecstatic acting and an overwhelming intensity of expressive means. A real event was The Life of Protopope Avvaakum (1982). The presentation was based on the autobiography, written in jail, of Avvakum Pietrowicz (1621?-1682) — a Russian Protopope, the founder and chief ideologue of the Old Believers, burnt at the stake. As in the case of Sorcery, the presentation did not retain the form of the original, nor did it follow its plot, but strove to convey the deepest meanings of the prototype. The essence of Avvakum's musical fabric were Orthodox church music and folk songs gathered by the ensemble in the villages of eastern Poland. Gesture and posture were worked out by analyzing, among other things, icons and the manner of movement characteristic of Orthodox priests and parishioners. Despite the problems with exegesis, there was really no doubt that Avvakum is a masterpiece, and that Gardzienice ranks among the masters of contemporary theater. Carmina Burana (1990), the ensemble's fourth show was received already as the work of mature artists having at disposal their own handwriting, their own vision of the world and of humankind. The presentation arose from two mutually complementary sources: a collection of medieval songs kept in the Bavarian Benediktbeuren Abbey used by Carl Orff in his secular oratorio, as well as love story of Tristan and lsolde. Carmina Burana — the monograph of love as Staniewski calls it is a shocking work in its simple but noble beauty. The presentations of the Center for Theater Practices do not have premieres because, just as in the case of any living organism, they never arrive at a point where one can say that they are ready, finished (this does not mean that they are lacking in structure, or that they are improvised). Their shapes, shades, sonorities change together with the time in which they live. At some point they die giving birth to another performance. It is in this way that, in recent years, Carmina Burana has been slowly fading into the past and the next show has been born — Metamorphoses, a theatrical essay according to Apuleius (1996). Metamorphoses is a fascinating attempt to revive ancient Greek music. This is an incredibly beautiful journey to the sources of the theatre. The result of this journey is not only a performance but also a record. In Gardzienice's presentations, there is no traditionally-conceived, linear plot, leading through a succession of events to a culmination and resolution. Events, words, emotions become tangled and intermingle, without, nonetheless, ever sinking into chaos. The basis of the order which regains [reigns?] among them is music — but really, using W. Staniewski's more precise term, musicality. The unique sounds and rhythms proper to each person, each situation, each action, movement, song, word, are linked on the basis of compositional principles derived from music. Musicality in Gardzienice replaces verbal discourse. I would advise the viewer who is about to encounter Gardzienice not to instantly try to explain what is being watched. It seems to me best to approach the shows of the Center for Theater Practices as a natural phenomenon, as a landscape passed by in one's travels. Nature does not bring a moral, instruction, lesson; but it cannot be said, nonetheless, that it is without sense, that encountering it does not leave a deep imprint, that it does not cause — sometimes small, sometimes very essential — change. Nature cannot be deciphered. One can only (even!) make it part of one's own experience. It is similar with the theatrical works of the Center. In this sense, Staniewski has succeeded at something not encountered in theater so far, but dreamed of by many — causing the audience to become participants in the event created by him, without becoming its authors. Work on successive theatrical creations is not all that occupies the members of the Gardzienice Center for Theater Practices. Much time and energy has been devoted to rebuilding and reviving the theater's headquarters — the annex of a 17th century palace and a park. WŁodzimierz Staniewski dreams of plans to transform Gardzienice into a multicultural village, a place for creative meetings of people coming from different traditions. And though this project has happened upon many obstacles and still remains in the sphere of dreams, such meetings have already taken place in Gardzienice, and still are doing so, also in the form of international artistic — academic conferences organized by the Center. Much work, effort and time has been devoted to the Road Trips of the whole group, and also to the travels of individual members, who have sought confirmation nearly everywhere in the world of their faith in theatre. These trips have often been associated with technical work, with presentations of Gardzienice's training methods (for instance the collaboration with Royal Shakespeare Company). The ensemble almost from the beginning has been engaged in educational activities, teaching groups of youth, conducting internship and theatrical workshops at its headquarters. In 1997 this work took on an institutional form in the Academy of Theater Practices. For Staniewski the theatre based on music has great value and meaning — it allows the whole human experience to speak. The Center created by Staniewski is the temple of life seen fully. However, the difficulty to create a work of art is first of all seen in the theatrical activities. These works of art in comparison to harmonia mundi would join the opposites in sound combination. Perhaps this is the meaning of Staniewski's enigmatic words: I look for Salvation in music. To be exact I Lookfor Salvation in the Theatrical Form. For me Salvation means the state of Artistic Concentration which I can obtain only through the creation of form relating creative elements to other worlds. DARIUSZ KOSIŃSKI |