Cecus: Agricola’s aesthetics of the blind

Although

encountering only some vestigial traces of the connection between

blindness and music in my researches into the subject, I nonetheless

very much believe that “the blind” or blindness appears to be a key

image for Alexander Agricola: the composer, singer and instrumentalist,

born in Ghent, who died in Valladolid in 1506 whilst on a journey with

the Burgundian-Spanish Chapel (which was also to be marked by the death

of Philippe le Beau). In a certain sense one could say that this “image

of the blind” is Agricola’s portrait, with Cecus non judicat de coloribus

potentially a musical self-portrait. However, on this recording I have

tried to draw not so much a portrait of Agricola himself, as to trace

the path of “the blind” in his music and that of other music directly

connected with it.

What I want to develop here is not so much a

simple analogy with music (in a certain way wouldn’t that mean that we

need also to consider deafness as a condition in composing/performing?)

but to reflect the more complex specific functioning of visuality and

acoustics in late medieval thinking. In general, like painters and other

artists, musicians do not develop written down theories of art, but

manifest them by images, albeit musical ones. In that way such images

become significant and it is only through repetition of them that you

can identify those theories.

I acknowledge that an inherent

danger lurks in attempting to develop a kind of aesthetical logic of

blindness in the art of Agricola based on traces and connections drawn

from contemporary writings and anecdotes. Such an apparently far-fetched

enterprise might be literally a case of walking in the dark, but

nevertheless I am convinced of a hitherto unknown aesthetic practice in

the heart of the polyphonic tradition around 1500. Moreover, this

approach presents a musical aesthetics in a much broader context than

music theory whilst remaining squarely within its own subject.

A blind man does not make judgements about colours

To

consider the question first of the identity of the blind person in our

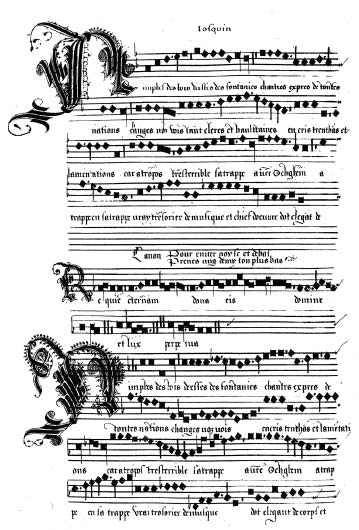

recording, there is a remarkable piece written by Alexander Agricola,

typically-known by the title Cecus non judicat de coloribus (“A

blind man does not make judgements about colours”), a large three-voiced

textless work in two parts (although in some early sources it is

accompanied with titles that seem to refer to a sacred motet, but these

could be descriptive as well).

Hans Neusidler, who made an

arrangement for lutes thirty years after Agricola’s death remarked that

singers of that time called the piece “Der Alexander”, whilst Marc

Lewon, a lutenist of today, has suggested that “Cecus” was Agricola

himself. More prudently I would claim that Cecus at least reveals

something of Agricola’s artistic being and style: the work appears to

have pedagogical aims and consists of a catalogue of all possible

clausulae, ostinati, hexachordal developments, etc. – such musical elements

being called colores. Is it strange then that such a practical manual – if we see in manus

a reference to the crucial role of tactility and hands for the blind –

received a title which refers to the blind? Yet there is a strong

Western tradition which ranks blindness alongside ignorance and

stupidity and on the surface it would seem that Agricola is sharing this

metaphorical use of blindness as equating to illiteracy (the lack of

sight making the blind incapable of any judgement or knowledge about

colours).

The title, Cecus non judicat de coloribus, acts

almost like a proverb and is a simplified abbreviation of a statement

made by Aristotle (and not a misreading, as Christopher Page claimed1).

Two celebrated medieval philosophers, the Augustinian Henry of Ghent

and the Dominican Thomas Aquinas, both used this idea to prove absence

of knowledge, but it was only the Franciscan John Duns Scotus who gave

it a positive turn; it showed him the possibility of speaking and

reasoning about concepts and ideas which phenomenologically could not be

seen. As a proverb the idea also appeared in musical theoretical

writings such as by the 16th century theorist Franchinus

Gaffurius

and earlier by the anonymous late 13th century writer known as Summa

Musice, who used the Aristotelian quotation in a concrete, physical

sense, rather than metaphorically, stressing the importance of the hand

as the preferred implement of music. The hand is in this context a

mnemonic instrument, an aide-mémoire not only

useful for the

blind, but for everyone who wants to learn the theory of music and in

this metaphorical sense passes from darkness of ignorance to the light

of knowledge. This is of course the “Guidonean hand”, used by music

students to learn the intervals and hexachords, the systematization

invented by Guido of Arezzo. The hand provided all the

notes of the musica recta, necessary for a music theorist. Guido stimulated the use of notation and the status of the musicus,

rising him up out of the bestial stupidity of mere performers. The

tactility of the hand allows for a system of theoretical, visual

meaning.

Two fiddle players from Bruges

With

this Agricola piece my contention is that the composer was pointing to a

physical state in selecting the title and we have found a very

interesting series of traces which prove that he was not using this

quotation as a joke, nor that he was facilely placing himself within

that moralistic tradition of considering blind people to be idiots (if

there was any humorous intent on Agricola’s part it would have been in

the same complex and ambiguous way as in a painter such as Hieronymus

Bosch). My hypothesis is that Agricola regarded blindness as a physical

and spiritual condition of his métier. The clue to this is to be found in a little annotation to the work Cecus

in the Cancionero de Segovia, a source which has often been linked to

the chapel of Philippe le Beau and Juana de Castilla, of which Agricola

was a member. Next to the title of the piece can be read “Ferdinandus et

frater ejus”. Reinhard Strohm has clearly shown that these two brothers

were the famous blind fiddlers Carolus and Johannes Fernandes who were

at that time living in Bruges but had been working at the French court

of Charles VIII, probably at the same time as Agricola’s employment

there2.

The celebrated theoretician Johannes Tinctoris

had been highly complimentary, in his De inventione et usu musicae,

about the brothers’ playing (Carolus played the superius and Johannes

the tenor), of which he had had personal experience in Bruges.

Additionally, these two musicians were the sons of the blind Castilian

fiddler Jehan Fernandes, who moved to the Burgundian court in the middle

of the 15th century (along with his fellow blind colleague Jehan de

Cordoval) and whose own virtuoso playing was described by Martin le

Franc, astonishing

both Binchois and Dufay. We don’t know whether

this pair of generations of virtuoso performers playing polyphonic music

represents merely the tip of an iceberg of a tradition of blind

musicians, but, in any case, they were taken very seriously in circles

of polyphonic musicians in France and the Netherlands. They were

recognized as intellectuals, even to the point of holding university

professorial positions in letters (including in Paris).

The “inner eye”

In

terms of how music was learned and executed, the condition of a blind

musician implied, by definition, a manual, tactile way of performing,

relying on the oral tradition and on the inner writing of the memory.

Appropriate scores would be necessarily found in the mind, having to be

read with a sort of inner eye, which brings us to a sense of revaluation

or rehabilitation of the blind person as someone who “sees” more

profoundly, who “sees” the invisible reality of things.

As far as

Agricola is concerned, we do not know if he was blind himself – but I

would not be astonished if he was. In any case, he probably was the

composer who wrote the most visually-focused music, not only in the

metaphorical sense of a visibility with the inner eye, but because of

the tactility of the lines and traits. He was a real painter in the

physical, tactile sense, of the sort that wanted to amaze, to “blind”.

Of course, his aesthetics of the tactile is synonymous with the

aesthetics of blindness. To enter the logic of the blind you need to

accept

this tactile perception.

The blind leading the blind

Concerning

this question of tactility and visuality in polyphonic practice it is

worth considering other yet more incidental and certainly almost

entirely neglected details of singing polyphony. Reference to

iconographic materials can prove very valuable here. I have always

wondered how singers in a chapel would be standing when they were

singing and often the relevant iconography has reminded me of a group of

blind people guiding each other with hands on shoulders. Such

miniatures and drawings are the immobile counterpart of Bruegel’s The blind leading the blind,

yet the immobility that they represent is only an apparent one and in

reality the singers do not cease to accelerate their invisible sounds.

Whilst standing still, their raison d’être is movement in sound

and whilst standing together, touching each other, guiding each other on

different invisible tracks, some of them “sing upon the book”, placed

on a large music stand. Additionally, some of the singers in these

miniatures are wearing large spectacles in order to be able to read the

notes of music (this could, admittedly, be a mere symbol designed to

stress their status as litterati).

There is a well-known

miniature of the French court chapel at the time of King Charles VIII,

showing singers grouped around a large stand, yet with all attention

focused on an extravagant singer with such a pair of glasses, Johannes

Ockeghem. However, as Fabrice Fitch has suggested, not only is Ockeghem

represented in this painting but probably also Agricola as well3. Here, my

interest

is more conceptual than strictly biographical. Is it a coincidence that

this miniature is about visibility? This would be stressed by the men

reading the manuscript: the remarkable man with the large spectacles and

in front of him (we might almost forget to see them), the blind leading

the blind, with the typical pose of the blind man with the hand on his

guide’s shoulder. But the guide seems also to be blind, given the way he

appears to be needing to touch the manuscript (or is he holding a sort

of

small paper in his right hand?). It is as if the miniature is wanting

to communicate to us, “we are able to read, we have the right pair of

glasses, but at the same time we are like blind men, touching and

guiding each other because we are not reading”. Therefore, touching as

the opposite of reading or better still, as a more profound reading.

The “tactile” musical score

Blindness

can be considered therefore as being linked to tactility but also to

the ability (or inability) of reading the score. At that time musical

practice was of course not bound to the written score nor to the

possibilities of notation and was still largely embedded in an oral

delivered tradition within which written notation functioned as a useful

instrument. It was the dream of Guido de Arezzo that the written score

would bring light into the darkness of dependency of what was learned by

tradition, where the staves would make possible a performance without

memory, without interpretation. What he didn’t understand was that

seeing was never a question of perception but always one of memory. To

Guido, memory was something related to previous times, and moreover, a

faculty stuck with repetition from which novelties could never emerge.

The blind man was someone literally linked to accidents, adding them

like more ornaments, and by chance. Following this argument you could

consider the blind man as being liberated from the slavery of a visual

score. Although influenced by this – how many interpretations have not

stressed Agricola’s borrowing of ex tempore styles and ractices? – we

should consider the situation on another level, beyond the duality of

orality and writing.

Even orality works with a sort of mental

score, an invisible score in the air so to speak, but we do not need to

imagine such a score in the same way as visible, written-down ones. It

is not a sort of ideal, “super score” in the Platonic sense, but rather

an operative mode, a machine. And the question for Agricola was a

functional and operative one: how do you make or trace a line, how do

you dive into it, how do you engage in performing a complex of lines,

how can we bring tradition and memory to a limit

so that we experience the appearance of something new?

Agricola’s

aesthetics of the blind is the emblematic side of his aesthetics of the

tactile (it is operative, manual and manipulative). The space in which

it operates is an invisible, dark, virtual one: it can be touched or it

touches one to be perceptible. If one is not prepared, walking in such a

space is disorientating, indeed, blinding. It was perceived in this way

around 1500. The opposite of such a

tactile aesthetics of experience is an aesthetics of judgment (of visibility and distance).

Polyphony and the visual

One of the clearest formulations in the context of polyphony and the visual is to be found in the treatise De natura cantu ac miraculis vocis by the Dutch humanist Mattheus Herbenus of Maastricht (as has been studied in recent times by Rob C Wegman4).

Within this treatise, the compositional approach of Agricola is subject

to a thorough-going critique, appropriate to its time naturally, but

within which it is contrasted to the methods employed by two

contemporaries in particular – Weerbeke and Obrecht (and should we today

be thinking of considering in that same company Pierre de la Rue,

Champion and even Josquin? The image in the early 16th century of

Josquin as a genial but bizarre and fantastic composer has also recently

been described to us by Wegman5). If one reads remarks by

Glareanus criticizing Josquin there is no need to hesitate, in that

examples of his preferred aesthetics are given as: the possible imprint

in the memory,

the guarantee of a proper transparent space, the

monochromatic use of colours, the fixed point of view of the gaze as

well as not changing or many points of view, the simplicity and syllabic

text declamation, the slowness of movement and the avoidance of speed,

the avoidance of multiplicities, dazzling effects, swift sounds which

vanish immediately.

All this seems to describe the ideal of a

renaissance perspectivist space. Staying within vocabulary appropriate

to an aesthetics of blindness one might add that the transparent

renaissance space is of course a cliché. It receives its visual truth

from its common sense status. But art historians as early as Aby Warburg

have always propagated a much more complex and heterogeneous view. A

blind space is a progressive space, a tracing, an experience from

within. If this is a landscape, it is an inner one, not a

panoramic view.

Agricola’s visual and tactile style

It

is not without reason that visual metaphors seem to be the most apt to

describe Agricola’s style. Fabrice Fitch has summarized in two articles

recently the most important elements of Agricola’s style6.

The “advised” use of visual and tactile features – “because the physical element is

experienced

very directly in performance, most immediately by those engaged in

enacting it” – is striking. Fitch, first of all, stresses the gestural

character of Agricola’s phrases. A line is a gesture, a trait, an

allure, at once visually essential and hardly perceptible, fixable: here

we are at the heart of Agricola’s ambiguous play of the blind. The

second feature is the high quantity of notes and speeds with which they

appear, all leading to an extremely intricate surface density. Of course

this is hardly a play of metaphors: is it not the surface which is

touched by the blind person? Is not surface quality of the only

importance to a blind, able to touch and feel it? The musical space of

Agricola is what lies between the visual and the sound: a haptic space.

The third feature is about the undermining of points of reference –

often played by cadences, making a multiplicity of lines without stops

or rests, going in all directions, be it gothic lines and ornaments or

more spatial, landscape verticality and deepness. Fitch remarks: “the

frequency of cadences in Agricola undermines their perception as

syntactical units,

and hence their functional effectiveness”. Here,

we are very close to Herbenus’ criticism. Troubling the perception of

cadences is one approach; another is, using, what Fitch calls very

aptly, a “blind adence” and “one of Agricola’s favourite devices”: a

sort of musical cul-de-sac, presenting the apparent features of a

cadence in one voice without the necessary functional features in

another. What Fitch describes is in fact the parcours (course or

route) of the blind person, lacking overview, but being in the middle of

things, leading into dead alleys. Musical or rhetorical procedures are

never used to clarify space, but on the contrary are used to blur the

distinctions and to enforce the density of the surfaces. The disaster

and chaos of infinite possibilities and of growing imperceptibilities is

affirmed here. A fourth feature is the ad hoc character of much of

Agricola’s procedures, a typical blind procedure in two meanings: first

of all because the blind person is lacking overview and deciding on the

spot where to go; secondly because it stresses the position of the

performer/improviser, always blind to himself and to his performance on

the moment of his acting, searching in the book of his experience and

memory, activating parts of it, making new, unforeseen connections. The

excitement of the listener is for a large part linked to the knowledge

that the operator is only partly conscious of what he is doing, not

seeing the musical lines he is drawing – and if not recorded not even

afterwards – leaving behind in this sense not even a trace.

Colour blindness and the disparates

Next to a sort of rehabilitation of the condition of the blind, it is maybe not unimportant to point to the fact that musici counting on the Guidonean hand are by definition colour blind: the hand provides you with all of the musica recta but not with the musica ficta,

the invisible colores in the sense of chromatic intervals, not written

in the score. In the logic of visibility and transparency, colours,

chromaticisms, coloraturae are troubling and blind proper space. Erasmus

said about Dürer that he painted what could not be painted because it

was pure movement or it transgressed the visual sense: the winds, and

even more so, the voice.

In the logic of the blind, Agricola

seemed to be able to transpose in music what was a capacity of the gaze

or of no senses at all: the inner eye. However, if Agricola’s

fascination with the gaze, the eye and the blind were only limited to Cecus,

it would be hard to speak of an aesthetical logic, but this is not the

case. It is an element which he returned to (and maybe even more

frequently than we

are capable of identifying today). His most popular composition, for example, Si dedero sompnium oculis meis, originally one part of a matins response but reworked as an independent piece, is almost a berceuse

about the eyes being closed, the gaze whilst sleeping. Can the proper

meaning of this work be discovered through a consideration of

compositions by colleagues of Agricola which appear to act as parodies

on Si dedero (for example Si sumpsero by Obrecht, Si bibero by Ninot le Petit and Si dormiero by either La Rue or Isaac)?

Agricola’s Fortuna desperata

can also be considered as having a clear link with the gaze or with

blindness, even if it seems to be just a six-voice arrangement of a

three-voice original Italian song, albeit with all the deforming and

disturbing features described before. Recently, however, Andrea

Lindmayr-Brandl made some interesting comments on the visual aspects of

the only surviving written version of the song which appears in the Augsburger Liederbuch, leading one to the conclusion

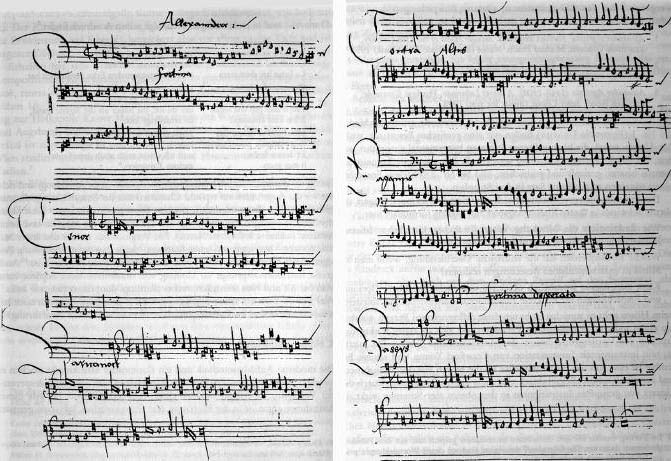

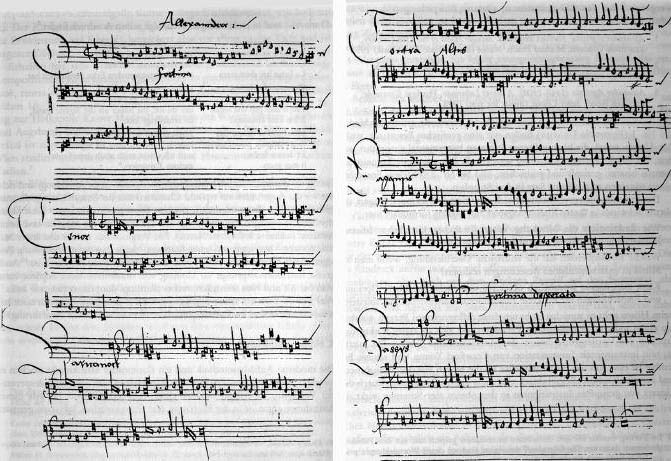

that the visual arrangement was an intrinsic part of the composition7. On the left we see the original simple voices and on the right the three flamboyant additions, colores, full of very small intervals, typical contratenor-loops and melismatic sequences in large or extreme tessituras.

This is Agricola’s personal, albeit less evident, contribution to what the Germans call Augenmusik,

of which Josquin’s lament on the death of Ockeghem –

written in black notation – is probably the best-known example.

If one wonders why Agricola should arrange Fortuna desperata

in this way, I believe that there is a reason, one that would be quite

obvious for every art lover living in Spain or the South of Italy around

1500. The answer is to be found in the work’s title: in Spain there

used to exist a popular genre of poetry called disparates, a nonsensical, fantastic form which, in the north, was called fatrasie. In a recent article on art at the court of Philippe le Beau, Paul Vandenbroeck related these disparates as being the Spanish name for the chimères, drolleries, grilles painted by

Hieronymus Bosch8. In the poetical disparate the eye of the subject (“I”) is somewhat overexposed, blinded in a way that leads to an experience of madness. The disparate

unfolds

a surface in continuous metamorphosis, with changing flows of

signification, transitions of content and formal transformations, all

circulating in a sort of irrational order. Listen to the music of Fortuna desperata and you can hear that it is precisely what Herbenus would have disliked: too many notes at once! Agricola’s disparates push the original version into a quasi-ecstatic landscape

easily comparable with other late-Gothic flamboyant art. The ear is touching, almost seeing.

Mémoires

Blindness

by overexposure is one thing, but an eye can also be underexposed and

there was an art form related to this and this acts as another key theme

on this recording: that of the gift of tears in late Burgundian society

(the other capacity of the eye). Perhaps no other society developed

this power so actively. The connection between the art of polyphony and

the eye is the eye’s capacity to weep, to cry, to lament, investing the

mémoire for its commemorating possibilities.

The French have always cultivated this link between the eye (oeil), sorrow (d’oeil / deuil ) and the expression of what goes beyond human capacities (dieu / d’yeux), be it in Agricola (Je n’ay deuil / d’oeil), Jean Molinet (habis de dueil / larmes d’oeil

) or the 20th century writer and poet Edmond Jabès. The underexposure

of the eye is clearly shown in the faceless figure of the Burgundian

pleurant whose crying face is fully covered by the huge scapular of his

habit. We cannot see his tears, nor his eyes, as to express his own

deprivation of sight, rather like someone wearing sunglasses in the

dark. There is an intimate connection between crying and weeping, in

their visual and

auditory representations; it is as if there are no cries possible without tears, and vice-versa. It is here that the mémoire as Trauerarbeit

and as the art of memory is most actively reflecting a synaesthetic

experience or practice beyond representation: travail dueil / d’oeil /

d’yeux / dieu. A memorial is also a portrait, but a veiled one, a

portrait made and seen in tears, a troubled image, as described by

Jacques Derrida in his famous book, Mémoires d’aveugle9.

At the same time it is a portrait of the person who composed it and for

this reason we have added two “blind” pieces, the theatrical Absalon fili mi, and the less common De profundis clamavi,

praised and criticized by Glareanus, both once ascribed to Josquin, but

now considered to have been composed by “ghost-writers” and late

brothers-in-arms of Agricola, Pierre de la Rue and Nicolas Champion10.

BJÖRN SCHMELZER

adapted by Mark Wiggins

Notes

1 Christopher Page, Summa Musice: a thirteenth-century manual for singers, Cambridge, 1991. Read Giorgio Pini’s Scotus on knowing and naming natural kinds, in History of Philosophy Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 3, 2009 for a nuanced interpretation of the medieval reception of Aristotle’s statement.

2 Reinhard Strohm, Music in Late Medieval Bruges, Oxford, 1985. See also: Warwick Edwards, Agricola’s songs without words: the sources and the performing traditions, in Trossinger Jahrbuch für Renaissancemusik, 6, 2006, pp. 83-121.

3 Fabrice Fitch, Agricola and the rhizome: an aesthetic of the late cantus-firmus Mass, in Revue Belge de musicologie, 59, 2005, p. 85. The topos of the blind man and his guide is analyzed by Kahren Jones Hellerstedt in an article published in Simiolus, 13, 1983, pp.163-181.

4 Rob C Wegman, The crisis of music in Early Modern Europe, 1470-1530, New York, 2005.

5 Rob C Wegman, The other Josquin, in Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 58, 2008), pp. 33-68, and And Josquin laughed . . .: Josquin and the composer’s anecdote in the Sixteenth Century, in The Journal of Musicology, 17, 1999, pp. 319-357.

6 Fabrice Fitch, Agricola and the rhizome: an aesthetic of the late cantus-firmus Mass, in Revue Belge de musicologie, 59, 2005, pp. 65-92, and Agricola and the rhizome II: contrapuntal ramifications, in Trossinger Jahrbuch für Renaissancemusik, 6, 2006, pp. 19-58.

7 Andrea Lindmayr-Brandl, Das Alte und das Neue – Agricolas “Fortuna desperata” in Interpretationsvergleich, in Trossinger Jahrbuch für Renaissancemusik, 6, 2006, p. 190.

8 Paul Vandenbroeck, Schoonheid en/vanuit waanzin. Een existentiële en esthetische band rond 1500, in Filips de Schone. Schoonheid en waanzin, Brugge/Burgos, 2006.

9 Jacques Derrida, Mémoires d’aveugle: L’autoportrait et autres ruines, Paris, 1990.

10 Patrick Macey, Josquin and Champion: conflicting attributions for the Psalm Motet De profundis clamavi, in Uno gentile et subtile ingenio, in Studies in Renaissance music in honour of Bonnie J Blackburn, Turnhout, 2009, pp. 453-468, and Honey Meconi, Another look at Absalon, in Tijdschrift van de Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 48, 1998, pp. 3-29