Danse et Chanson / Grand Désir

granddesir.com

medieval.org

ACD HJ 043-2

2009

1. Guillaume DuFAY. Or me veult de bien [4:03]

2. Maitresse [1:53]

3. Gilles BINCHOIS. L'ami de ma Dame [4:08]

4. Vil lieber zit. Jo götz [1:04]

5. Vil lieber zit [0:57]

6. Conrad PAUMANN. En Avois [1:47]

7. Marc LEWON. Corona [3:07]

8. Triste Plaisir (Basse Danse) [1:39]

9. Gilles BINCHOIS. Triste Plaisir [3:55]

10. Modocomor [2:40]

11. Modocomor Bystu die rechte [2:38]

12. Johannes OCKEGUEM. Petitte Camusette [1:52]

13. Aspasia NASOPOULOU. Ballad I (2005) [6:13]

14. Aspasia NASOPOULOU. Ballad III (2005) [4:00]

15. Gilles BINCHOIS. Dueil angoisseux [2:18]

16. Franckurgenti [1:22]

17. Guillaume DuFAY. Franc cuer gentil, sur toutes gracieuse [4:13]

18. Filles a marrier (Basse Dance) [2:04]

19. Filles a marrier [1:12]

Grand Désir

Anne-Marieke Evers & Anita Orme Della-Marta

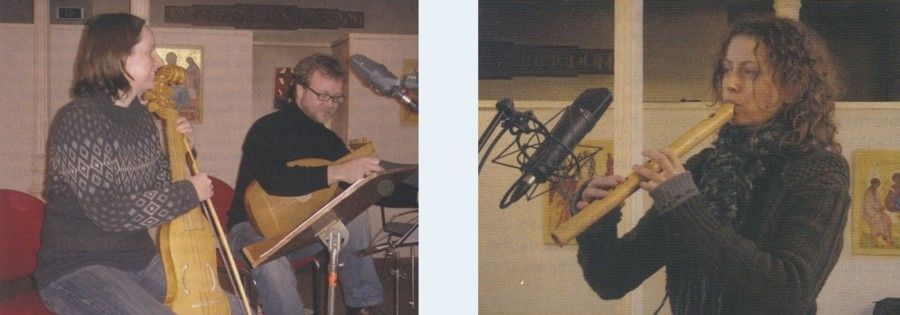

Anne-Marieke Evers, Mezzo-Soprano

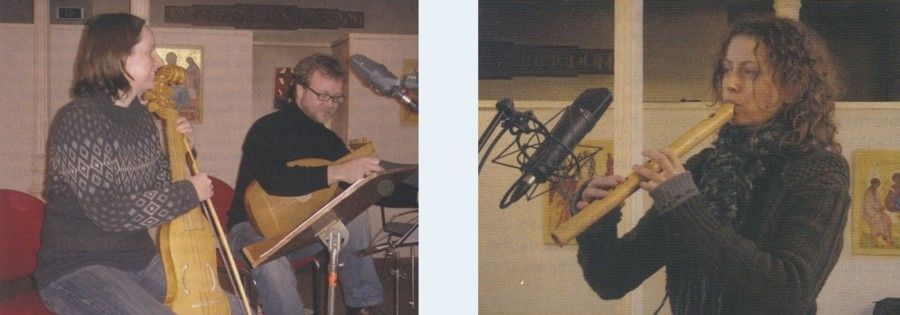

Anita Orme Della-Marta, Recorder / Harp

Marc Lewon, Lute

Elizabeth Rumsey, Viola d'Arco / Recorder

Stephanie Brandt, Recorder (track 10, 11)

Recording date: December 3, 4, 5 & 6 2008

Recorded at the Lukas Church, Ermelo,

by Skarster Music Investment C.V.

Production & distribution: Skarster Music Investment

Producer: Jos Boerland

Recording, editing and mastering: Jos Boerland

Cover & Design: Jos Boerland

Text: Anthony Fiumara & Anita Orme Della-Marta

English translation: Anita Orme Della-Marta

French translation: Frédéric Dorfmann

German translation: Christian Salewski & Marc Lewon

Ⓟ & © 2009 by Aliud Records, Skarster Music Investment

www.aliudrecords.com

www.skarstermusic.com

Grand Désir | Danse et Chanson

De basse danse is een

statige hofdans die een eeuw lang floreerde vanaf het midden van de

vijftiende eeuw. De oorsprong van het genre ligt waarschijnlijk in

Bourgondië, maar de basse danse vond weerklank aan verschillende hoven

in Europa. De term wordt al gebruikt in een gedicht van de uit Toulouse

afkomstige priester, monnik en troubadour Raimon de Cornet (ca. 1320),

maar over de exacte danspassen vinden we niets tot de vroege vijftiende

eeuw.

De twee belangrijkste bronnen voor de muziek van de Franse

basse danse zijn te vinden in een manuscript in Brussel (Bibliotheque

Royale de Belgique, Ms 9085, ca.1470) en in L'art et instruction de bien danser

(ca. 1496) van Michel Toulouze: beide manuscripten uit de late

vijftiende eeuw, beide terugblikkend op de muziek van eerder die eeuw.

Samen met nog een aantal kleinere bronnen bevatten deze handschriften

ongeveer vijftig cantus firmi, die in lengte variëren tussen de

vierentwintig en tweeënzestig noten, genoteerd in trage semibreves

zonder ritmische variatie. Waarschijnlijk diende bij de basse danses de cantus firmus

in lange notenwaarden in de tenor als eenstemmige basis voor

meerstemmige instrumentale improvisatie. Het bewijs voor die praktijk is

te vinden in enkele uitgeschreven meerstemmige voorbeelden,

bijvoorbeeld dat op de tenor-melodie Re di Spagna.

In zijn

studie over de basse danse wijst musicoloog Daniel Heartz in verband

met het uitvoeringstempo op de relatie tussen de muziek en de

daadwerkelijke gedanste passen: elke noot van de basse danse-melodie

correspondeert volgens hem met één figuur van de dans. Die figuren

bestonden ieder uit vier bewegingen van gelijke duur, terwijl de

begeleiding zes tellen besloeg. De dansers bewogen dus in twee tegen

drie ten opzichte van de muziek, op hun tenen, in een golvende beweging.

Het

Brusselse basse danse-manuscript verklaart de naam van het genre uit

het karakter van de gedanste figuren: “Et se nomme basse danse [...]

pour ce que, quant on la danse, on va en paix sans soy demener, le plus

gracieusement que on peut”. Met andere woorden: de dans bestond uit

niets anders dan een rustig schrijden, zo bevallig mogelijk en zonder

verdere gestes.

In het al eerder genoemde gedicht van Raimond de

Cornet, de eerste melding van de basse danse, stelt hij: “Een jongleur

leerde snel stanza's en vele kleine verzen, cansos en basses danses”.

Door de basse danse in een adem te noemen met een aantal gezongen

genres, lijkt het hier alsof de basse danse in oorsprong vocaal werd

uitgevoerd, al zijn geen voorbeelden van overgeleverd.

Dat de

verbinding met de vocale muziek wel degelijk te leggen is, bewijst deze

cd. Geinspireerd door het onderzoek van Frederic Crane naar de basse

danse, bevat deze cd een aantal cantus firmi, of fragmenten

daarvan, die een gelijkenis tonen met enkele tenoren van chansons uit

dezelfde tijd. Hierdoor wordt de vraag naar de oorsprong van deze cantus firmi meer dan slechts een vraagteken.

In de tenoren van Maitresse en Triste Plaisir is bijvoorbeeld een gelijkenis van een aantal noten te vinden in vergelijking met de chansons L'ami de ma Dame en Triste Plaisir. Een grotere overeenkomst is te vinden in de tenor Portugaler. In vergelijking met Dufay's chanson Or me veult de bien esperance mentir (dat op zijn beurt weer over dezelfde tenor geschreven is als Dufay's Portugaler)

komen de eerste acht noten van de dans met het chanson overeen. Hoewel

de meeste basse danses overeenkomsten laten zien tussen de tenor-lijnen

van de dans en het chanson, toont de tenor van de basse danse Filles a marrier juist een bijna gehele gelijkenis met de cantus van het gelijknamige chanson.

Niet

alleen de oorsprong van de basse danses vraagt om opheldering, maar ook

de uitvoeringspraktijk daarvan. Slechts enkele voorbeelden van

diminuties over een basse danse tenor zijn uit de late 15e eeuw

overgeleverd (ervan uitgaand dat onze tenoren inderdaad als tenoren

bedoeld waren en niet als volwaardig uitgeschreven composities). De

stijl waarin Grand Désir hun basse danses uitvoert, is een samensmelting

van verschillende factoren zoals basiskennis van de choreografie van de

basse danse, overgeleverde diminuties gecomponeerd over basse danse

tenoren en de stijl van diminuties die gebruikt wordt in verschillende

15e eeuwse bronnen met instrumentale bewerkingen (zoals de Fundamentum Organisandi van Conrad Paumann en het Buxheimer Orgelbuch).

Afgezien van Filles a marrier

zijn de verdere chansons op deze cd gecomponeerd door Guillaume Dufay

en Gilles Binchois, twee van de grootste componisten van de 15e eeuw. De

chansons zijn naar de traditionele poëtische vormen van de formes fixes gecomponeerd en laten een enorme variatie aan textuur zien, vooral door hun complexe ritmiek en motieven.

Zoals

de vijftiende-eeuwse basse danse, het chanson en de intavolaties van

die chansons op deze cd naar elkaar verwijzen en met elkaar verweven

zijn, zo componeerde de uit Griekenland afkomstige componiste Aspasia

Nasopoulou tenslotte een actueel antwoord op die oude vormen. Dat begint

als bij de titel Ballad, die verwijst naar de narratieve liedvorm die

sinds de Middeleeuwen bekend was. Oorspronkelijk refereerde de ballade

aan dansliederen, maar bij Nasopoulou is het een sololied met

begeleiding. Zoals Gilles Binchois al deed, gebruikte de Griekse

componiste ook voor haar werk de lyrische poëzie van Christine de Pizan

(ca. 1364 — ca. 1430), een van de eerste vrouwen met een professionele

literaire carrière. Pizans persoonlijk getinte gedichten en de

combinatie met het oude instrumentarium vormden voor Nasopoulou de

inspiratiebron voor een nieuwe invalshoek voor beide gegevens. De

componiste liet zichzelf naar eigen zeggen leiden door de emoties en

beelden van de gedichten, maar ook door de pure klank van de

instrumenten.

De archaïsch aandoende, verstilde composities van

Nasopoulou contrasteren niet eens zo fel tussen de vroege

renaissancemuziek. Met haar polyfone gemeander bleef de Griekse dicht in

de buurt van de oude muziek. Zeker in het geval van de eerste Ballad,

waar ze verschillende middeleeuwse modi gebruikte — de tweede

contrasteert wat dat betreft door zijn chromatische karakter. Toch

klinken de twee Ballads ontegenzeggelijk als van deze tijd: golvend van

ritmiek en kruidig van toonmateriaal ademen de half gesproken, half

gezongen liederen herinneringen aan een gedroomd verleden.

Grand Désir | Danse et Chanson

The basse danse is a

stately courtly dance whose origin can be traced to Burgundy. It was

enthusiastically taken up at numerous courts throughout Europe and

flourished for a century long from the middle of the 15th century

onwards. That courtly dance existed before this is clear: for example, a

description of the basse danse can be found as early as ca. 1320, in a

poem by the Toulousain priest, friar and troubadour Raimon de Cornet. No

information however concerning its choreography can be found until the

early 15th century.

The Brussels (Bibliotheque Royale de Belgique, Ms 9085, ca.1470) and Toulouze (L'art et instruction de bien danser, ca. 1496, by Michel Toulouze) manuscripts are the two most important musical sources of the French basse dance;

although both manuscripts are dated to the late 15th century,

stylistically their music resembles the earlier decades of the century.

These manuscripts, along with a few additional sources, contain around

fifty cantus firmi, varying in length between twenty-four and

sixty-two notes, notated in slow semibreves without rhythmical

variation. It is assumed that the cantus firmi of these basse

danses notated in long semibreves provided a monophonic basis for

polyphonic instrumental improvisation. Evidence for such a practice can

be found in some polyphonic examples written out on the tenor-melody Re di Spagna.

Regarding

performance-tempo, Daniel Heartz points towards the relation between

the music and the actual choreography in his study concerning the basse

danse: according to Heartz, each semi-breve of the basse danse-melody

corresponds to one figure in the dance. Each figure consisted out of

four movements equal in length, while the musical accompaniment took up

six beats. Thus, the dancers moved fluidly on their toes in a

three-to-two proportion to the music.

An explanation to the

origin of the basse danse's name can be found in the Brussel manuscript

and refers to the character of the dance: “Et se nomme basse danse [...]

pour ce que, quant on la danse, on va en paix sans soy demener, le plus

gracieusement que on peut”. Thus, the dance consisted of nothing more

than calm striding, as graceful as possible without further gestures.

The

first reference to the basse danse in the poem by Raimond de Cornet

mentioned in the first paragraph stated: “An enchanter quickly memorized

stanzas and small versus, cansos and basse danses”. By mentioning the

basse danse in one breath with some sung genres, could suggest that the

basse danse was originally performed vocally, although no examples of

such a practice still exist.

That a connection can be made to

vocal music, is suggested by the present recording. Inspired by Frederic

Crane's research on the basse danse, this CD contains a number of cantus firmi and fragments of cantus firmi, which show striking resemblance to the ‘tenors’ of some contemporary chansons, turning the question of these cantus firmi's origin into more than just mere speculation.

The ‘tenors’ Maitresse and Triste Plaisir, for example, share a few notes with their associated Chanson L'ami de ma Dame and Triste Plaisir. The ‘tenor’ Portugaler shows a greater resemblance to Dufay's chanson Or me veult de bien esperance mentir (which shares the same tenor as Dufay's Portugaler) in that the first eight notes are similar. Unlike most basse danses that show resemblance with the tenor-lines of their associated chansons, the basse danse Filles a marrier shows almost complete similarity to the cantus of its chanson.

However

it is not just the origin of the basse danses that arouses speculation,

but also their performance practice. Few examples of composed

diminutions over basse danse tenors have survived from the second decade

of the 15th century (presuming that our tenors are indeed meant to

serve as such and not as a completed composition). The style in which

Grand Désir performs the basses danses has therefore been determined by

several factors such as basic knowledge of the basse danse choreography,

some surviving examples of diminutions written over basse danse tenors

as well as the style of diminutions used in several 15th century sources

of intabulations (such as Conrad Paumann's Fundamentum Organisandi and the Buxheim Organbook).

Apart from Filles a marrier,

the chansons presented on this CD have been composed by Guillaume Dufay

and Gilles Binchois, two of the greatest composers of the 15th century.

The musical forms of the chansons follow the traditional poetical forms

of the so called formes fixes and their chansons show an extreme variation of texture, mostly due to complex rhythms and motives.

A

contemporary answer to the 15th century basse danses, the chansons and

their intabulations, was composed by the Greek composer Aspasia

Nasopulou - the title Ballad already referring to a narrative song known

since the middle ages. Originally the term Ballad referred to

dance-songs, but Nasopulou's Ballad is a solo-song with accompaniment.

Like the composer Gilles Binchois, the Greek composer also used the

lyrical poetry by Christine de Pizan (ca. 1364 — ca. 1430) for her

compositions. Pizan was remarkable for being one of the first women with

a professional literary career. Nasopoulou used Pizan's subjectively

coloured poetry combined with early instruments as a source of

inspiration. This allowed for the creation of a new point of view

towards various elements. Quoting the composer herself, she was led by

the emotions and images of the poetry, but also by the pure sounds of

the instruments.

The archaich and tranquility immanent in the

compositions by Nasopulou do not contrast vigorously to the early

renaissance music. With her polyphonic meander, the Greek composer

remained close to early music. This is especially evident in the first

Ballad in which she used several medieval modi. The second Ballad

presents a pleasing contrast with its polyphonic character. In spite of

this, both Ballads sound contemporary: flowing rhythms and pungent

tonal material breathing the half-spoken, half-sung chansons reminiscent

of a dreamt past.

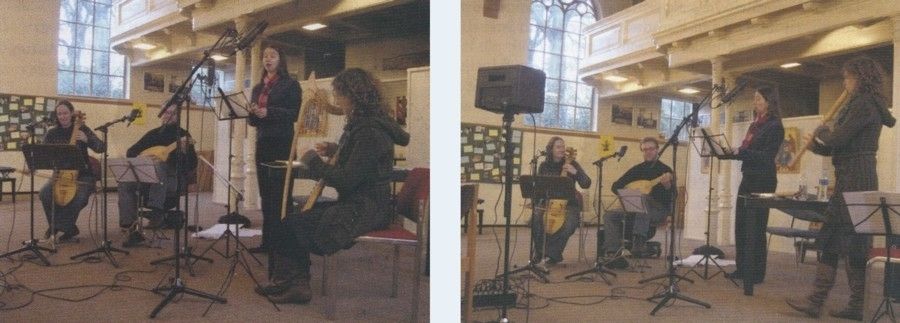

Grand Désir's artistic directors Anita

Orme Della-Marta (Recorder, Harp) and Anne-Marieke Evers (Mezzo-Soprano)

met at the beginning of their musical studies at the Conservatorium of

Amsterdam in September 1997, where they specialised both in contemporary

music as well as medieval and renaissance music. Later in their

careers, their paths led them to pursue further studies in medieval

music at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, Switzerland, where they met

the other ensemble members of Grand Désir.

Grand Désir performed

their première in the 'Fringe' programme of the Utrecht Early Music

Festival 2005. The ensemble has given numerous performances and radio

recordings since in the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland and Australia.

In July 2009, Grand Désir won the audience award during the York Early

Music Festival Young Artist's Competition 2009.

Grand Désir likes

to work with different musicians for each individual programme, thus

creating the flexibility to obtain the perfect instrumentation for each

project. The large repertoire of Grand Désir, as well as their interest

to combine contemporary and medieval music, makes Grand Désir a unique

ensemble both for early as well as contemporary music.