medieval.org

amazon.com

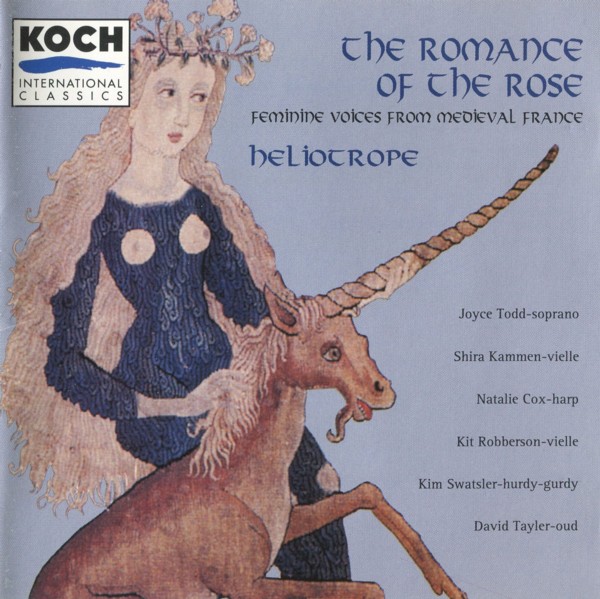

Koch International 7103

1995

medieval.org

amazon.com

Koch International 7103

1995

01 - Estampie Roine Blance [2:33]

adapted and arranged J. Todd

Cox, Kammen, Robberson, Todd

02 - A chantar m'er de so qu'ieu non volria

[8:31]

Trobairitz lyric: Contessa de DIE ca. 1200 Paris, Blb. Nat. MS

F.fr.844

Todd, Cox, Kammen, Swastler

03 - Three songs from Guillaume de Dole, The Romance of the Rose

Todd, Kammen [9:00]

a) Siet soit Bele Aye [1:54]

anon. 13th C; melody J. Todd

b) La Bele Doe siet au vent [3:38]

c) Quant revient la sesons [3:28]

anon. 13th C; melodies adapted from Gace BRULE

04 - Estampie Guiraut Riquier [2:36]

arranged J. Todd

Cox, Kammen, Robberson, Todd

05 - Per joi que d'amor m'avegna [10:10]

Trobairitz lyric: CASTELLOZA ca. 1200, New York, Morgan Library 819;

melody: Guiraut de BORNELH

Todd, Cox, Kammen, Robberson

06 - Bele Yolanz en ses chambres seoit

[4:57]

anon. chanson de toile, 13th C Paris, Bib. Nat. F. fr. 20050

Todd

07 - Bele Doette as fenestre se siet [9:30]

anon. chanson de toile, 13th C Paris, Bib. Nat. F. fr. 20050

Todd, Cox

08 - Estampie Marcabru [3:08]

Arr. J. Todd

Kammen, Tayler, Todd

09 - Estat ai en grue cossirier [4:18]

Trobairitz lyric: Contessa de DIE, Rome, Bib. Vat. 5232;

melody: Raimon de MIRAVAL

Todd

10 - Estampie Bele li gossi [3:41]

Arr. R. Whelden/S. Kammen

Cox, Kammen, Robberson, Todd

11 - Jherusalem, grant damage me fais [4:47]

anon. chanson de femme, 13th C. Paris, Bib. Nat. F. fr. 844;

melody: Gace BRULE

Todd, Kammen, Swastler

Heliotrope

Joyce Todd

Joyce Todd · soprano, percussion, harp

Natalie Cox · harp

Shira Kammen · vielle, rebec

Kit Robberson · vielle

Kim Swatsler · hurdy-gurdy, monochord

David Tayler · oud

Recorded at St. Vincent's School for Boys, San Rafael, CA

Mastered by Peter Nothnagle

#1 2 4 5 10:

Recorded July, 1995

Produced and engineered by Jack Vad.

#3 6 7 8 9 11:

Recorded November', 1995

Produced and engineered by David Tayler.

The Tradition

The poetic traditions of medieval France produced the first great

flowering of vernacular lyric poetry in Western Europe. This recording

features songs by the women troubadours or trobairitz from

southern France, and also women's songs or chansons de femme

from the trouvère tradition in the North. The songs of the trobairitz

were composed in Old Occitan (langue d'oc) while the anonymous

poets of the chansons de femme composed their songs in Old French (langue

d'oil). These repertoires, though composed in different languages

and regions, are two branches of the same tradition. In fact, the words

troubadour, trobairitz and trouvère are all

derived from the same Occitan root, "trobar," meaning "to compose, to

invent, to look for."

The troubadour tradition, of which the trobairitz and trouvères

are distinct parts, began as early as the 11 th century and continued

until the mid-13th century. This poetic and musical culture was not a

written culture; thus, the poems of the troubadours, trobairitz and

trouvères developed within an oral tradition, in some cases for

as long as 150 years before being anthologized in manuscripts in the

13th and 14th century. These manuscripts were compiled after the

tradition had for the most part ceased, and scholars are not sure

whether there were any previous written sources for the songs or

whether they were written down from memory by the scribes. The

troubadour tradition's long "prescribal" existence has been pieced

together by historians despite the scarcity of written evidence, and it

seems clear that the poets relied on memory as the primary means of

transmission of their works.

Though most written literary traditions value permanence, originality

and ownership, the troubadours, trobairitz, and trouvères could

not depend on a stable text since their works were likely to undergo

changes as they were learned and relearned by various singers. Poems

were learned by memory, and were commonly sent to an intended audience

via a "messenger" who was perhaps another poet or jongleur, a performer

who may have been in the employ of a poet or acting independently. The

presence of this oral tradition is evident in the fact that many of the

poems exist in different versions in several manuscripts. In the

troubadour tradition, singers who could improve upon a song were

celebrated while those who misunderstood the essence of a song, and

thereby corrupted it, were criticized. Troubadour scholar Amy Van Vleck

writes that this tradition depended on the interplay between "the

original poet, the performer (who recomposes), and the auditor (who

reconstructs the message in his mind) . . . [where] each new learner of

a song speaks partly with the voice of the original poet and partly

with his own voice."

The trobairitz repertory is unique in being the largest body of women's

lyric poetry to have been composed in the medieval period. The poems of

the sixteen trobairitz who are named in the manuscripts were composed

between 1170 and 1260, during the latter part of the troubadour

tradition. Much research has been directed in recent years toward the

status of women in medieval culture. Historians have documented that

women experienced a general decline in social position from the

10th to the 13th century, yet they have also shown that women did

temporarily recover several important legal rights during a period

roughly corresponding to the activities of the trobairitz. These

rights, to hold property, administer estates, and create wills, are

indications of a society which fostered the participation of noble

women in diverse aspects of medieval culture.

The comparatively large trobairitz repertory provides evidence that the

tradition of courtly love or fin amors in which these poets

worked did not exclude the participation of women. Women were not only

the objects of desire of the male poets, but also singers, jongleurs,

composers, and suitors in their own right. Marriages were not expected

to be accompanied by love, and, especially for women, were often

arranged for political expediency and at a very young age. In this

culture courtly love was more likely to be expressed outside the

boundaries of marriage. According to the conventions of courtly love, a

poet vows selfless service to a beloved, who was often the spouse of

another noble. These conventions can be viewed as a code of love which

served as the inspiration for poetry as an end in itself, as well as a

practical means to attain the object of desire.

The Songs

The two trobairitz represented on this recording, the Comtessa de Die

and Castelloza were active in the early 13th century. Though nothing is

known for certain of their lives or identities, their poems present two

highly individualized voices within the trobairitz repertory. The

Comtessa de Die's "I must sing of that which I would rather not" (A

chantar m'er de so qu'ieu non volria) laments the singer's betrayal

of her loved one, while at the same time reminding her lover and her

audience of her fine qualities as a beautiful and courtly woman. This

same confident tone, which combines lamentation with a declaration of

self-worth, is maintained in the Comtessa's "Lately I have been in

great distress" (Estat ai en greu cossirier). In this seduction

song, the singer, having loved to excess (sobrier), describes

the pleasure her chevalier would feel if she let him lean his head

against her breast, and hold him in her bare arms (bratz nut).

In the last verse she makes the conditions of the seduction clear when

she says: "I would gladly have you in my husband's place, if you would

swear to do my bidding." In contrast to the Comtessa's pride, the poems

of Castelloza reveal a suitor who feels powerless to succeed in

attaining the object of her desires. In the song, "For the joy that

comes to me from love, I'll no longer care to rejoice" (Per joi que

d'amor m'avenga) the singer seems to relish the defeats of love,

thanking her beloved even for her sufferings, for these are all that

she receives from him. Castelloza's songs give voice to a deep despair

that has earned her the title of "dark lady" of medieval song, and, in

her own time, her finely crafted poems brought her honor and stature as

a trobairitz.

Many of the women's songs from the North were chansons de toile,

sometimes translated as "spinning songs," in reference to the activity

which occupied women throughout the year, the spinning of yarn for

weaving. These chansons are romantic narratives which tell the

stories of female protagonists, who are usually of noble origins. The

songs typically begin by naming the heroine: bele Doette, bele Yolanz

or bele Aye; they then describe what she is doing: sitting by the

window, sewing or reading a book. Such formulaic beginnings introduce a

great variety of narratives, some tragic, some seductive, and some

humorous. Bele Doette narrates the story of a young woman whose

husband Doon is away at a tournament. Such tournaments were popular

peacetime opportunities for knights to practice their battle skills.

Knights could benefit financially by capturing their competitors, and

these contests were not infrequently fatal. In the song, a messenger

arrives to tell Doette the news that Doon was killed while jousting.

Doette's grief prompts her to become the powerful abbess of an abbey

which she builds for those who suffer from love. The song's beautiful,

repetitive melody and plaintive refrain express Doette's lament. Bele

Yolanz, sounding a lighter note, describes the meeting of two

lovers after a long separation. This song ends happily, for the lovers

"lie together, in the French manner, upon a fine bed."

The third source of songs for the present recording is the important

13th-century romance by Jean Renart: The Romance of the Rose or

Guillaume de Dole (not to be confused with the better-known Romance

of the Rose written by Guillaume de Lorris.) The "rose" of the

title refers not to the flower but to the heroine Lïenor's

birthmark, "the great marvel of the crimson rose on her soft white

thigh." In this story, Conrad, the King of Germany, falls in love with

Lïenor, sister to the gallant and brave knight Guillaume de Dole,

who has become the king's best friend. However, a jealous vassal (seneschal)

of the king, who fears his privileges will be usurped by Guillaume,

plots to ruin Lïenor's honor, and tricks her mother into telling

him about the "rose" on her thigh. The seneschal then claims to

have "deflowered" Lïenor, using the intimate knowledge he has

pried from her mother. Lïenor is thought guilty by all, including

her brother Guillaume, but through an ingenious plan, she manages to

outsmart the seneschal, prove her innocence, and marry the

king. Besides being of great interest to feminist literary scholars,

the Romance is important as a document of early 13th century

culture, diet and dress. It is also a unique source for medieval

chansons which are skilfully woven into the fabric of the narrative.

The present recording includes two chansons de toile sung in

the Romance by the heroine Lïenor, and a

trouvère song-fragment sung by a jongleuresse introduced as "the

beautiful Doette from Troyes."

The Music

The poems of the trobairitz and the chansons de toile have survived

almost entirely without melodies. This situation is not unusual since

out of all the songs in the medieval manuscripts, less than one tenth

appear with musical notation. When melodies do accompany the poems, the

notation does not, as far as we know, indicate rhythm, nor does it give

any indication of meter, tempo, or accompaniment. I have drawn on

melodies from contemporaneous manuscripts to create settings for these

poems, a solution which is fully consistent with the medieval

predilection for borrowing, adapting, and copyrighting from existing

sources. The instrumental accompaniments and the instrumental dances

have been created using medieval forms as guidelines, though they are

nevertheless a modern musician's contribution to the repertory. Perhaps

in this performance we can assume a place in the troubadour tradition

by speaking partly with the voices of the original poetesses, and

partly with our own.

© 1995, Joyce E. Todd

University of Pennsylvania