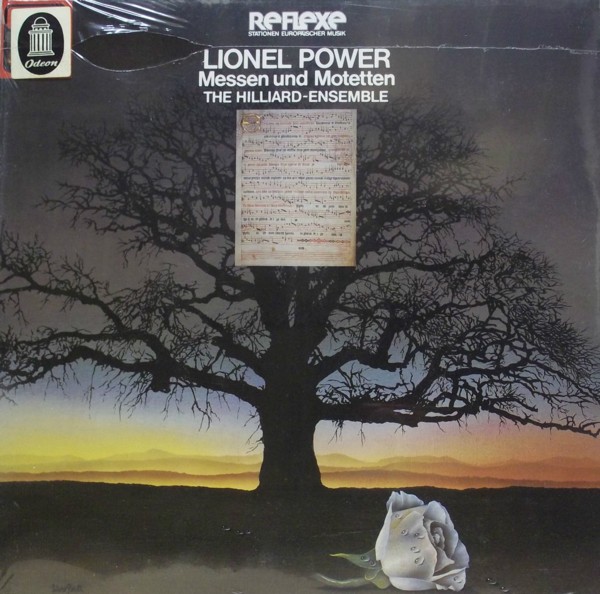

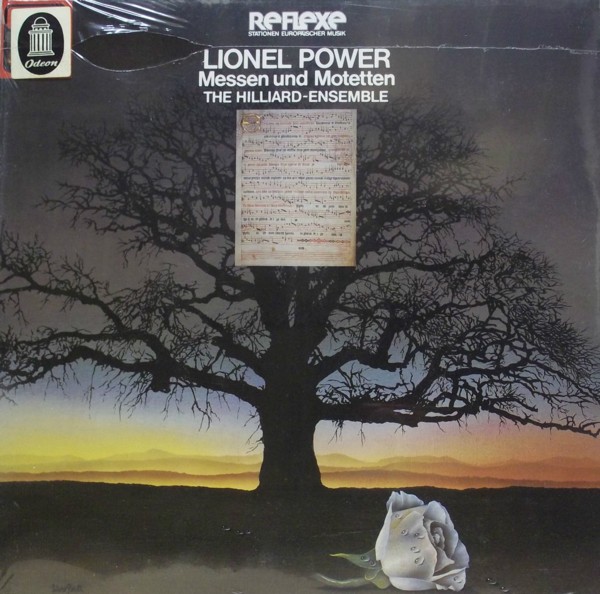

Leonel POWER. Masses & Motets

The Hilliard Ensemble

medieval.org

EMI "Reflexe" 1C 069 46 402 (LP, 1981)

EMI "Reflexe" 63 064 (CD, 1989)

1. Ave Regina [1:55]

motet à 3 / 1 2 4 6 7 5 3

2. Gloria [3:17]

à 5 / 5 1 7 6 3 4 2

3. Beata viscera [1:31]

motet à 3 / 1 5 7 6 4 3 2

4. Credo [4:19]

à 2 ... à 5 / 5 1 7 6 3 4 2

5. Sanctus [3:35]

à 4 / 1 3 6 4 5 2

6. Agnus Dei [3:55]

à 4 / 1 3 6 4 5 2

7. Salve Regina [7:03]

motet à 3 / 1 2 6 4 5 2

MISSA 'Alma redemptoris mater'

1 2 6 4 5 3

8. Gloria [3:48]

9. Credo [5:29]

10. Sanctus [4:19]

11. Agnus Dei [6:14]

12. Ibo michi ad montem [3:11]

motet à 3 / 1 3 5

13. Quam pulchra es [4:16]

motet à 3 / 7 6 3

THE HILLIARD ENSEMBLE

Paul Hillier

1 David James, countertenor

2 Ashley Stafford, countertenor

3 Paul Elliot, tenor

4 Leigh Nixon, tenor

5 Rogers Covey-Crump, tenor

6 Paul Hillier, baritone

7 Michael George, bass

Ⓟ EMI Electrola GmbH

Digital remasterring Ⓟ by EMI Electrola GmbH

Aufgenommen: 8.-11.IX.1980, Ev. Kirche, Seon (CH)

Produzent: Gerd Berg

Tonmeister: Johann-Nikolaus Matthes

Titelseite: Roberto Patelli (CD)

LEONEL POWER

In the early years of the 15th century, English music was recognised as

the leading force in Western music and John Dunstable (d. 1453) as its

leading composer. It does not diminish Dunstable's reputation to say

that the music of his older contemporary Leonel Power (d. 1445) is of

comparable stature and that several younger composers also contributed

to the eminence of the English sound, known abroad as la contenance

angloise. This sound in fact derived from a mixture of French and

more traditional English styles, together with some rhythmic impulses

from Italy — but it was indeed a sound. The sweetness of thirds

and sixths was exploited for practically the first time in Western art

music, expanding the harmonic language and encouraging the use of

fuller sonorities, which has often been a trait of English music. To

this Leonel added his own peculiar brand of waywardness that happily

defies all analysis.

In the sound of a particular music lies its immediate appeal which will

either attract a listener or not: but there is always another aspect

awaiting our deeper appreciation (though ideally the two are

inseparable): its structure. In the structure of music is based the

true foundation of its expressive power, and it is in the history of

musical form that Leonel's significance lies no less than in the

sonorities of his music. The major achievement of this English school

was to establish the cyclic tenor Mass as a form of major importance,

and Leonel's Missa "Alma redemptoris mater" is probably the

earliest example we have of such a work.

The bulk of Leonel's earlier music is found in the Old Hall manuscript,

(OH), an important collection of English polyphony (mostly settings of

individual Mass movements) dating from the late 14th century. In some

ways this collection marks the culmination of medieval English music

and it is unusual, perhaps significantly so, in providing us with the

names of many of its composers. Anonymity is one trait common to most

aspects of medieval art that has been equally uncommon ever since. The

medieval composer was a craftsman in sound whose music sought to

reflect the harmonious proportions of the universe (the music of the

spheres) and the perfection of God; self-expression was not his

immediate purpose. This sense of order and number plays a profound part

in medieval music, and while it has never ceased to be important, has

again today become a prominent aspect of the composer's craft. In the

sudden flush of names provided in OH, Leonel's clearly dominates; over

twenty pieces can be credited to him, while no other composer reaches

double figures.

Leonel is first encountered among the records of November 1419 for the

Household Chapel of Thomas, Duke of Clarence, (who was Henry V's

brother, and thus heir presumptive to the throne) where he appears as

clerk and instructor of the choristers. Later, after Clarence's death,

he was received into the fraternity of Christ Church Cathedral Priory,

Canterbury, on May 14th, 1423 — an honour rather than an

appointment. In September 1438 he appears on a legal document, also in

Canterbury, styling himself "armiger" (gentleman). Then from 1439 he

appears regularly in the cathedral archives at Canterbury, where his

duties seem to have been light and to have involved serving as the

first Master of the Lady Chapel choir. A private chronicle records that

he died on June 5th, 1445, within the cathedral precincts, and was

buried the following day. In addition to his music there has also

survived a treatise on counterpoint — designed as a practical

guide in the training of choirboys, and doubtless belonging to this

latter period in his life.

These few facts, a bare skeleton, may be tentatively fleshed out

following the researches of Professor Bowers. It may be assumed,

working backwards, that Leonel was born in about 1375, so that his

earliest extant music, in OH, probably dates from around the turn of

the century. Henry IV's sons were Henry (later Henry V), Thomas (Duke

of Clarence), John (Duke of Bedford) and Humphrey (Duke of Gloucester);

Thomas was created Duke of Clarence in 1412 and it may be assumed that

this household, including the Chapel, was established at the same time.

Leonel probably served from this period until 1421, when the Duke was

killed while fighting in France. During his time in the Chapel Leonel

would have spent at least a year in northern France in areas then

occupied by the English. When his brother Henry returned to England for

his wedding, Thomas remained as Lieutenant of France. At his death, the

household would have been dispersed and the next period in Leonel's

life, 1421-1438, is obscure.

His recorded fraternity with Christ Church Priory in 1423 is no proof

that the then remained in Canterbury or had any duties there, although

he may already have begun to feel an identity with the place where he

certainly lived out his final years. It is generally accepted that

Dunstable served in the Chapel of John, Duke of Bedford —

Clarence's younger brother; and it has been proposed that Leonel may

have done likewise. There is no proof of this at all, but it would

partly explain why so much of these composer's works survive in foreign

sources as Bedford spent much time abroad, and also why an important

work (the Missa Rex Saeculorum) survives in two sources,

attributed in one to Dunstable and in the other to Leonel.

The final period of Leonel's life involved him in work at Christ Church

Priory. The establishment there of a Lady Chapel as a secular adornment

of the monastic Cathedral liturgy fits the overall pattern of religious

life at the time. The Lollard heresy, seeking amongst other things to

simplify the service ritual and its elaborate music, provoked a

reaction that was very favourable to the English musician, who was

encouraged to produce a yet richer art to confute the teachings of

Wycliffe and his followers, (whose spiritual descendants eventually had

their way a century later under the guidance of Thomas Cranmer). This

receptive atmosphere must have contributed in part to the preeminence

of English music at the turning of the 14th century, as found in OH,

leading to the creation of la contenance angloise.

The Music — Old Hall

The simplest style of music found in OH is a continuation of the

traditional English Discant technique — often little more than

the harmonisation of a given melody, usually plainsong. The unique

fascination of the OH music derives from the fusion of this harmonic

sensibility with certain more complex and essentially linear styles

from abroad. These were a French "chanson" style in which the melodic

interest was concentrated in the top line, isorhythm (mostly the

preserve of motets during the C 14th), and from

Italy a secular canonic style. All three of these emphasised rhythmic

and melodic independence in the upper voices, supported by more

sustained lower parts. Leonel's OH music is most closely influenced by

the "chanson" style, though he also displays complete mastery of the

sort of rhythmic and metrical complexities which represent the style

recently described as the "C 14th avant-garde", Mathews de Perugio,

Ciconia and others).

Ave Regina — A votive antiphon to the Blessed Virgin Mary

that was usually sung after Compline. The style is English Discant, but

of a developed kind; the chant is paraphrased and the cadences somewhat

decorated, a mensuration change divides the piece in two and the parts

occasionally cross. Beata viscera (a setting of the Communion

text at Mass for the B.V.M.), is simpler in style and survives, not in

OH, but in a manuscript from Aosta.

Gloria — The piece is a subtle yet powerful blend of

melody, rhythm and sonority. The abundant use of syncopation, the

varying phrase lengths and the use of imitative entries create an

imposing choral sound that is lyrically offset by the solo passages,

equally flexible in rhythm yet sustaining an overall melodious quality.

The chorus at first consists of two texted parts supported by two

lower, quasi-instrumental parts (all parts are vocalised on this

recording). But in the final section the top voices divide into three,

creating a five-part texture that is uncommon for the period and makes

for an exciting climax at the Amen.

The Credo is so similar to the Gloria in terms of

material, style and structure, that they must be seen as a pair, and

this Credo, though anonymous in the manuscript, as clearly

attributable to Leonel. The longer text produces correspondingly longer

phrases and more use is made of fast declamation of the text. There is

again a final five-part section, but here Leonel also employs the

common medieval device of polytextual setting, so that three sets of

words are sung simultaneously.

Sanctus — The two upper voices weave an imitative duet

that is both rhythmically buoyant and melodiously abundant, while the

lower two voices supply the harmonic basis (the Tenor following quite

closely the plainsong Sanctus, though they too join in the game

of imitation and rhythmic ingenuity. There are four sections, marked by

changes of mensuration. Although the Osanna chant is the same

both times, Leonel varies the melodic treatment (as well as the

different mensuration); the second Osanna also creates a sense

of a reprise of the Sanctus.

The Agnus shows such strong stylistic and even melodic

similarities to the Sanctus as to suggest a conscious pairing.

There is a greater rhythmic variety in the lower voices and the chant

is considerably ornamented in the Tenor. There are again four sections.

Missa "Alma redemptoris mater"

This Mass by Leonel is probably the earliest one in which all the

movements are linked by a common cantus firmus. Looking back it is easy

to regard this as an obvious development, but in fact it was not so

inevitable. The Ordinary of the Mass (the unchanging portion) was

served by chants that bore no particular musical relationship to each

other: and when these chants were used as canti firmi for polyphonic

writing, the diversity of the original material did nothing towards

linking the various movements musically. Furthermore, the texts are of

two utterly different kinds — short and repetitive in the Kyrie,

Sanctus and Agnus, long and declamatory in the Gloria

and Credo. Thus it is not surprising to find in Machaut's Messe

de Nostre Dame that the short-texted movements are in one style

(isorhythmic motet), and the two longer texts in another (conductus

with strophic variation). Any musical unity emerges more as the

composer's autograph (in terms of style and use of musical formulae)

than from any overall structural device. OH consists mostly of separate

Mass movements grouped in the manuscript, as was customary, according

to liturgical function: thus all the Gloria settings are

together then the Credos and so on. There are instances of

paired movements and these, as might be-expected, are Gloria—Credo

and Sanctus—Agnus groupings.

The implications therefore of Leonel's Missa Alma redemptoris

are historically very significant, having regard for the importance of

the Mass as an art form throughout the Renaissance and indeed through

to the present day. It had long been the practice to adapt existing

works or melodies into new music, particularly so in the case of motet

composition. Owing perhaps to the sanctity of its central position in

the liturgy, the Mass was the last portion of the rite to become

subject to purely musical considerations. Leonel took a major step in

this direction by choosing a non-liturgical chant (the Marian antiphon Alma

redemptoris mater on which to base his Mass. In the medieval

fashion he laid out the chant in various note-lengths interrupted by

rests in a seemingly arbitrary manner — certainly with no regard

for the original melody. The rhythmic scheme thus arrived at for the

Tenor is used unaltered in all four movements. This was the standard

method used for isorhythmic composition, except that usually the Tenor

was then proportionally varied. The rhythmic scheme (Talea) and the

melodic design (Color) were sometimes of different lengths, so that as

they were repeated they coincided at different points. A common

practice was simply to diminish the Talea section by section in

proportions such as 3 : 2 : 1, producing a sense of acceleration and

climax. Leonel does not so alter his Tenor — nevertheless, that

medieval delight in number symbolism, though never so apparent in

Leonel's music as in Dunstable's, does seem here to be in evidence.

Leonel's Tenor is constructed in two sections, one consisting of 56

measures in triple time, the other of 84 measures in duple time. The

implied 3 : 2 proportion is in a sense illusory as the actual number of

single beats in either section is the same; 56 x 3 = 84 x 2 =168. The

whole design of the Mass is thus: (I and II represent the sections

built on the Tenor, the duets are outside the scheme though related to

it).

part / tenor - (bars in triple measure) - (bars in duple measure) -

(single beats)

Gloria

I · (56) · (--) · (168)

II · (--) · (84) · (168)

Credo

duet · (36) · (--) · (108)

I · (56) · (--) · (168)

duet · (--) · (18) · (36)

II · (--) · (84) · (168)

Sanctus

Credo

duet · (9) · (--) · (27)

I · (56) · (--) · (168)

II · (--) · (84) · (168)

Agnus

I · (56) · (--) · (168)

duet · (32) · (--) · (96)

II · (--) · (84) · (168)

If we then take the Tenor itself, counting sung beats and rests* we

find:

I 48 / 12*/ 48 / 24* / 36

II 40 /16* / 76 / 16* / 20

We can quickly discern the importance of 2 (or its double, 4), 3, 7 and

12. The factors of 168 are 23 x 3 x 7; 12 = 2 + 3 + 7; leaving 7 out,

12 = 23 x 3.

In primitive cosmology the stars imaged the will of the gods. The

phases of the moon indicated to early man a special relationship

between 4 and 7. The great astrological numbers were 4, 7, and 12.

Christian symbolism had no trouble in fitting itself to these ancient

patterns. 7 indicated harmony, the 7 tones, the 7 planets, the Universe

(created in 7 days); it came to symbolise the Virgin Mary (and much

else). 12 was seen as another form of 7 (3 x 4; 3 + 4). There are 12

signs in the zodiac; 12 hours of the day (daylight); Christ chose 12

disciples, indicating himself as the spiritual day/ light. Medieval

sculpture often represents the disciples in 4 groups of 3 x 8 (23) is

also important; as 1 more than 7 it indicated regeneration, baptism and

eternity. It would be tiresome to enumerate here all the possible

interconnecting arithmetic and imagery, and there is certainly a danger

of pressing these ideas too far. However, the incidence of 7 in a Mass

based on a Marian antiphon is possibly significant and there is

certainly an overall sense of numerological design.

Returning to purely musical considerations, the plainsong Tenor also

furnishes material for the two upper voices. The chant begins by

climbing through the third, fifth and sixth to the octave and then

winds back down to the third. The melodic contours thus created recur

throughout the chant in various inversions, retrogrades and melodic

extensions, giving Leonel the basis for many related shapes in addition

to those occasions when he paraphrases the chant more directly (e.g.

the duets in the Sanctus and Agnus).

Having established his formal framework, Leonel works freely within it

to create a variety of texture and treatment that is astonishing in a

Mass for three voices. The verbal declamation does not seek to be

naturalistic, although it frequently reflects the overall sense of the

words; the music mixes together points of imitation and parallel

movement, chordal sonority, contrasting subdivisions of metre, all

types of syncopation and pulse suspension; there are solo sections

played off against the Tenor as well as the formal duet sections

without the Tenor.

This music, as in the case with all but the simplest types of medieval

polyphony, is essentially soloist music, best sung by one or two voices

to a line. The use of instruments (other than the organ) in church was

rare and music that today may seem instrumental was almost

certainly vocalised — this applies to chant-tenors as well as the

lower parts of freely composed works (such as the OH Mass movements).

Three Marian Antiphons

Salve Regina is a rather unusual though expressive work and to

understand it we must look at the text. In England it was customary to

supplement the standard text of the poem with some extra lines, this

addition being known as a trope. This has the effect of surrounding and

high-lighting the three exclamations O clemens, O pia, O dulcis

Maria in a way that balances the first part of the text up to Ostende.

Following a traditional division of the latter portion of the text into

alternately solo and full sections, Leonel sets the troped texts as

duets to contrast with the otherwise three-part texture.

The truly unusual feature of this work, however, is that Leonel uses

the plainsong melody of Alma redemptoris mater rather than that

of Salve regina. In the first section the complete melody is

freely paraphrased almost exclusively in the top voice. The plainsong Salve

regina melody is however hinted at in the three exclamations. It is

difficult to say whether this mixture of music and text sources is a

deliberate illusion or the result of adaptation of an earlier work that

had been left incomplete.

Quam pulchra es - lbo michi ad montem

In these late works Leonel's style is very far removed from that of his

early career and foreshadows many developments that took place later in

the century. The voices are equally balanced and independently

melodious, a wider pitch range is explored, a warm major triadic

harmony is sustained and there is constant variety in the word setting.

Held chords, melismas, rhythmic figures, imitation and syllabic

declamation all display a strong sensitivity towards the verbal sense

and articulation, a concern which belongs more to the Renaissance than

the late Middle Ages. The two works chosen here, both settings from the

Song of Songs, form a contrast in range and colour. Quam

pulchra es exploits unusually low regions for the time. Beginning

with a brief duet, it continues in three parts leading to a cadential

pause and then a change of metre at Ibi dabo tibi. lbo michi

lies much higher, the tenor voices encompassing quite a large range; it

begins directly in three parts, there is a central duet, but with no

pause or changes of metre. Both works end with an Alleluya.

© Paul Hillier, 1981