medieval.org

amazon.com

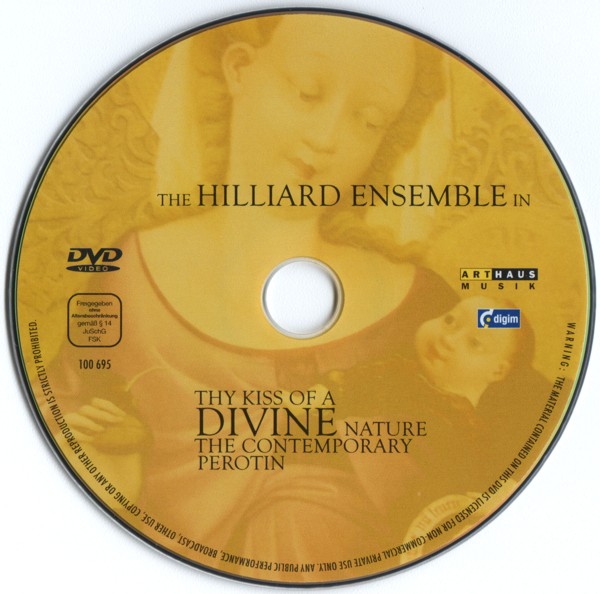

Arthaus Musik 100 695

2005

A film by Ulrich Aumüller, inpetto filmproduktion

lenguage version: German

subtitle languages: GB, F, SP, JP

sound format: PCM Stero, DD 5.1, DTS 5.1

picture format: 16:9

running time: 95 minutes

medieval.org

amazon.com

Arthaus Musik 100 695

2005

A film by Ulrich Aumüller, inpetto filmproduktion

lenguage version: German

subtitle languages: GB, F, SP, JP

sound format: PCM Stero, DD 5.1, DTS 5.1

picture format: 16:9

running time: 95 minutes

THE FILM “THY KISS OF A DIVINE NATURE” tells the extraordinary love story beteween heaven and earth. It also tells the story of the medieval composer, Perotinus Magnus, of the invention of polyphony and a new concept of time.

|

DVD 1. Perotinus' innovation 2. A letter to Martin Burckhardt 3. Leonin rehearsal 4. Rieman musical encyclopaedia 5. Cloister I 6. Music: Beata viscera (conductus) 7. Paris in the Middle Ages 8. Cloister II 9. Symposion I: Martin Burckhardt 10. Music: Laude jocunda (prosa) 11. The question of interpretation I 12. Cloister III 13. The question of interpretation II 14. Symposion II: Christian Kaden, sociologist of music 15. The question of interpretation III 16. Theatre rehearsal I: the black and the white Mary 17. Music: Descendit de celis I (organum) 18. The word becomes flesh (walk in the woods) 19. Music: Descendit de celis II (organum) 20. Theatre rehearsal II: the ear conception 21. Theatre rehearsal III: when God is no God... 22. Excursus: Perotin and the invention of money 23. Theatre rehearsal IV: tableau vivant 24. Symposion III: Jürg Stenzl, historian of music 25. Music: Alleluia nativitas (organum) 26. Symposion IV: dispute 27. Theatre rehearsal V: Mary as a letter 28. Music: Viderunt omnes (quadruplum) 29. Theatre rehearsal VI: flawless projection screens 30. Theatre rehearsal VII: the power of imagination 31. The betrayal of nature 32. Music: Dum sigillum (conductus) 33. Music: Benedicamus domini (organum) 34. Credits |

Bonus DVD The Perotin Symposion Who was Perotinus Magnus - Myth or History ? 1. Perotinus innovation, Jürg Stenzl, Historian of Music 2. Wealth of euphony - Christian Kaden, Sociologist of Music 3. The question after the question - Martin Burckhardt, Historian of Culture 4. Two concepts of time - Rudolf Flotzinger, Historian of Music 5. The astronaut Perotin - Martin Burckhardt, Historian of Culture 6. Is Aristotle the wrong provider of keywords (dispute I)? 7. The delivrery of the individual (dispute II) 8. The end Perotinus Magnus - The Vision of a Film Project 1. The beginning of the film 2. Music: Beata es virgo (offertorium) 3. The mother-of-God machine 4. The idea of a loudspeaker 5. Singing like Dervishes 6. Perotinus, the revolutionary 7. History of interpretation 8. Workshop atmosphere 9. Composing with Lego 10. The dawning of a new age 11. Music: Laude iocunda 12. Light finger 13. The immaculate conception 14. Music: Dum sigillum (conductus) 15. The beam of light 16. The cathedral of light 17. Body in body 18. Dances of Mary 19. God abdicates 20. Music: Viderunt omnes 21. From the idea to the realisation |

Bonus CD

1. Beata es virgo [1:57]

Offertorium/Graduale, 11th century

Descendit de celis [15:44]

3-part organum — Anonymous/Nôtre-Dame de Paris, after 1200

(according to the Florentine writings, 14r)

2. Descendit de celis [2:25]

3. missus ab arce patris [1:21]

4. Tanquam sponsus dominus [4:31]

5. Et exivit per auream [0:33]

6. Fac deus munda corpora [0:28]

7. Gloria patri et filio [2:01]

8. Et exivit per auream [0:34]

9. Familiam custodi [0:29]

10. Descendit de celis [0:59]

11. missus ab arce patris [1:22]

12. Facinora nostra relaxari [1:00]

13. Dixit angelus [1:47]

1-part Responsorium, 11th century

Gaude Maria [9:18]

2-part Responsorium — Anonymous/Nôtre-Dame de Paris around 1190

(according to the writings of Wolfenbüttel II, 48v)

14. Gaude Maria [0:45]

15. virgo cunctas hereses [1:19]

16. Gabrielem archangelum [3:44]

17. Dum virgo deum [0:40]

18. Gloria patri et filio [1:25]

19. Gaude Maria virgo cunctas [1:25]

20. Laude jocunda [2:41]

2-part prose — Anonymous/St Martial de Limoges around 1150

Descendit de celis & Tamquam sponsus [4:45]

2-part organum — LEONIN/Nôtre-Dame de Paris around 1180

(according to the writings of Wolfenbüttel I, around 1240)

21. Descendit de celis [1:27]

22. Tamquam sponsus [3:18]

Alleluia Nativitas [7:06]

3-part organum — PEROTIN/Paris after 1204

(from the writings of Wolfenbüttel II, around 1260)

23. Alleluia [1:30]

24. Alleluia [0:28]

25. nativitas gloriose [4:09]

26. clara ex stirpe David [0:59]

Beata viscera [9:29]

1-part conductus — Anonymous (PEROTIN?)/Paris after 1200

(according to the Florentine writings, around 1250)

27. Beata viscera [1:48]

28. Populus gentium [1:50]

29. Fermenti pessimi [1:52]

30. Legis mosaicae [1:51]

31. Solem quem libere [2:08]

Viderunt omnes [10:29]

4-part organum (Graduale of the 3rd Christmas Mass) — PEROTIN/Paris soon after 1200

(Magnus Liber, Florentine writings)

32. Viderunt omnes [3:30]

33. finis terrae salutare [0:52]

34. Notum fecit Dominus [5:41]

35. justitiam suam [0:27]

36. Dum sigillum [7:29]

2-part conductus — PEROTIN/Paris after 1200

(Unicum from the Florentine writings)

37. Benedicamus domino [2:36]

2-part organum — Anonymous/Nôtre-Dame de Paris, after 1200

(according to the writings of Wolfenbüttel II, around 1260)

The Hilliard Ensemble

David James — countertenor

Rogers Covey-Crump — tenor

Steven Harrold — tenor

Gordon Jones — baritone

Participants involved in the

preparation and research for

this film were

An den Recherchen und

Vorarbeiten für diesen Film

haben u.a. mitgewirkt

Martin Burckhardt, Claudia Burkhardt, Gösta Courkamp, Ulrich Engel,

Rudolf Flotzinger, Stefan Gagstetter,

David Hofmann, Christian Kaden, Ellen Hünigen,

Hanne Kaisik, Dorothea Kraus, Alina Kunkel,

Katharina Ortmann, Robert Paschmann,

Jürg Stenzl, Romy Weinhold, Hannah Nischwitz.

Thank you very much! Ihnen allen herzlichen Dank!

Impressum

A digital images DVD Production

www.digirn.de

Producer — Torsten Bönnhoff

Product manager — Mario Katscher

Project manager — Nico Heinrich

Supervisor Post Production — Rinaldo Seeger

Video Editing — Mathias Eimann

Audio — Thomas Vollmer

Video — Andreas Hirsing, Thomas Weyh

Menu Design — Felicitas Fröb

Authoring — Jürgen Weidig Marek Schuboth Christine Malerz

Test & Check — George Szathmári, Maria Teubner

Subtitles —

Michael Statz, Sandra Behrendt, Steven J. White, Raoul Weiss, Rob Hyde

comtext Leipzig

Booklet Text — Marcus Heinicke

Artwork — Thekla Trillitzsch

Translations — A.A.C. Berlin

© by digital images GmbH

Perotin and the history of music

are linked by an important chapter, even though future generations had

little to say about this French composer of medieval vocal music.

According to 13th century manuscripts, the composer lived from 1165 to

1220, or from around 1155/60 to 1200/05. For the presentation of his

music, however, it is not of importance whether this man Perotin was

also called Perotinus Magnus, or Magister Perotinus, or in which year he

was born, or when he died. After all, the name of Perotin is really

only a diminutive form of Petrus, and could have been used by many

individuals at that time. The name Perotin does not therefore identify a

tangible historical person, and the mere facts are more or less

shrouded in the obscurity of the Middle Ages. What is crucial, however,

is the conception of polyphonic music, which, 800 years ago, was

tantamount to a revolution. As master at the cathedral of Nôtre-Dame in

Paris and probable successor of the composer Leonin, Perotin played a

significant part in this revolutionary development. The organum of the

Early Middle Ages, a method of playing and composing where quint and

octave voices were added strictly parallel to the main voice, was

fundamentally transformed. Perotin created a notation for Gregorian

chants with several voices. He used a modal notation, which fixed the

rhythm of two, three or four voices and subordinated them to a temporal

metre. This rhythm of individual modi, used for the first time for

chants with two voices by Leonin, was organised more tightly. Perotin

subjected the original voice of the organum to strict rhythmic formulae,

with the choral melody having not just one, but two or three upper

voices slotted in like modules. Therein lies his special skill of

varying repetitions and themed combinations of upper voices. Like

clockwork, the voices weave rhythmically together and apart, and merge

again in the end to find a common metre. This new order of musical

structure characterises polyphonic musical language to this day, and it

is also the underlying idea of the film about the composer Perotin, who

himself is lost in obscurity, but whose music is a fascinating

experience in sound to this day.

Perotin and the film by Uli Anmüller

achieves an audiovisual symbiosis, which asks about the origins and the

basis of medieval music, philosophy, architecture and religiousness.

The film thus creates a musical painting with medieval chants by the

Hilliard Ensemble, accompanied by a scientific dispute, and choreography

by Johann Kresnilc. The chant, the dispute and the dance run like a

thread throughout the film; they weave around and together attempt to

bring Perotin's time and music back to life. The director did not so

much employ the classic documentary format with interviews and a

historical ambience, rather, his focus was on the presence of music and

the staging of the images and the participants.

The four

scientists Martin Burckhardt, Rudolf Flotzinger, Christian Kaden and

Jürg Stenzl, who were filmed in various places, such as the choir stalls

of Schleswig Cathedral, discuss the fundamentals of Perotin's music. In

the film, the scientists do not just engage in scholastic dispute, they

also play around each other as part of a staged workshop discussion.

Only, the workshop is a church; the church as a space where Perotin's

music can and was able to develop. The film also opens up another sphere

of experience; watching the renowned choreographer Johann Kresnik

creating a dance. Through the medium of dance, the choreographer and the

two dancers, Simona Furlani and Tanja Oetterli, look for ways and

possibilities to make the lyrics of Perotin's vocal music comprehensible

to us today. The worlds of medieval theology and of the modern

conception of art meet in order to find a degree of mutual understanding

in the artistic outcome. And in the end, when the scholarly dispute

about the appropriate way to judge Perotin's music historically, and the

choreographed dance as a video projection end up in the sacred space of

a church, interwoven with the chanting of the Hilliard Ensemble, the

film, in a contemporary way, shows the particular nature and the origins

of European culture in a literally multidimensional form.

As a

result of the difficult and time-consuming 3 year research for the film,

and the no less complex technical implementation involved, the director

and his team travelled to many locations in Europe. The church of St.

Petri, in Lübeck, was chosen as the projection room, which seemed

predestined for the idea of a visual staging with its bare, white walls

devoid of ornaments or furnishing. For tracking shots, sound recordings,

the conceptual implementation and other shots, the cathedrals of Laon,

Troyes and Schleswig, a village church near Pfullingen, as well as the

cathedrals of NôtreDame and St. Denis in Paris were used as models for

Perotin's work. The Gothic architecture of the French cathedrals with

their unique spatial effects and religiously-historical, architectural

language were thus not just cinematically transformed into the church in

Lübeck, they also served as symbolic, stone reflections for the 12th

and 13th centuries.

Perotin and the time

represents the philosophical dimension of polyphonic music and medieval

innovations, which the film is seeking to make comprehensible in today's

terms. As if on a journey through time, the film seeks to discover two

levels of Perotin's music and its revolutionary modernity. The first

discovery during the preparations for the film was that the rhythm of

the four-voiced chant is structured in time — it works only once it is

subjected to a fixed tempo. And how does that differ from the apparently

modern way a mechanical clock measures time? Only that neither the

mechanical clock nor polyphonic music is a creation of the modern age;

both were invented in the supposedly dark, medieval times of the 12th to

14th centuries. And Perotin is at the centre of this development, and

it is partly due to him that time is no longer perceived as something

that goes by as the rushing of the wind, as the change of seasons and

weather, as something cyclical. Rather, time becomes modern, so to

speak, it becomes measurable through the ticking of the hands, and

through the movement of the mechanism of a clock. Ever since, the flow

of time has thus been identified with the mechanical movement of a

clock. This philosophy of time, which is full of tension and which the

film illustrates acoustically as well as visually, even includes the

realisation that time, given its relativity, is measurable only to an

extent. Pero-tin uses precisely this way of measuring time before the

invention of the mechanical clock. But the idea is the same: time is

divided up into small modes, which are used to make music with four

different voices. The musical metre, which carries modes of the various

voices, works in analogy with the seconds, minutes and hours of a clock.

It is possible that Perotin was aware only of the musical aspect, and

not its philosophical significance. In retrospect, however, we know that

human awareness underwent radical changes at that time. And that is

another reason why Perotin is "our contemporary" — because he conveyed

to us an idea about how today's image of culture, and our understanding

of time was beginning to gain ground even then.

The second

dimension of Perotin's music which the film illuminates, lies in its

textual character. The Latin texts of the chants reveal a central theme

that was of crucial importance to medieval thought: the myth of the

virgin conception and birth, which was realised again and again not just

in texts, but also in church architecture and Christian iconography.

Numerous churches, such as Nôtre-Dame in Paris, were dedicated to Mary

as the mother of God, and she also represents the vessel for the

Messiah. Many medieval works of art depict Mary together with a heavenly

beam of light to show that she receives the truth. These processes have

to be explained by analogy to people of the 21st century. Cultural

historian Martin Burckhardt does just that in the film, explaining the

virgin birth using contemporary media theories. Thus understood, Mary

becomes the medium for the birth of the light figure of Christ, as the

pure, white projection screen onto which God's light is projected and

can be passed on. And just like the cinematic screen receives the beams

of light of the cinema projector and reflects human bodies, so Mary

produces the metaphysical body of God. This idea can be taken even

further; one could view the Gothic cathedrals with their light

architecture, and their eastern alignment towards the Messiah and

bringer of light in analogy with picture theatres, the cinemas of today.

The cinema produces light figures of its own. Such considerations, such

media-theoretic connections between then and now, between the Middle

Ages and Modernity, are, as the film illustrates, what makes Perotin our

contemporary, not least in this regard. In order to symbolise this

relationship, the church served as a projection space, as a

three-dimensional projection screen for animated and pre-produced

images. The film thus merges the metaphorical language of the 21st

century with the architectural and musical language of the 12th and 13th

centuries. As a play between heaven and earth, as a sign for old and

new, as proof that every age looks for its figures of light. And so the

dance of the two Marys, as a form of the mediaeval dance of Mary

projected into the church, is an attempt to receive the kiss of a divine

nature.

Perotin and the chant

of the Hilliard Ensemble turn the film into an experience of sound

which combines this 800-year old music with modern singing. For more

than 30 years, this vocal ensemble has artistically recreated the music

of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and worked with contemporary

musicians and composers. The four singers David James (countertenor),

Rogers Covey-Crump and Steven Harrold (tenor) and Gordon Jones

(baritone) make up this quartet which is world-famous for its exact and

exquisite interpretations. Because of the group's unmistakeable style

and their extraordinary musical skills, compositions have been written

especially for the Hilliard Ensemble. The ensemble, which was named

after the English painter Nicolas Hilliard (15471619), thus has a varied

repertoire, which spans 800 years of music from Perotin to contemporary

music.

The Hilliard Ensemble has also collaborated with the jazz

musician Jan Garbarek and the Estonian composer Arvo Part in novel

ways. The two recordings Officium and Mnemosyme, which the Hilliard

Ensemble produced in the 90s with Garbarek, was a big success with the

public and the press during the period of this crossover. As early as

1988, the vocal ensemble performed the Passio, by Avo Part, which later

led to other cooperations with Baltic composers, such as Veljo Tormis

and Erkki-Sven Tüür. The Hilliard Ensemble wrote the film music for the

Canadian film Lilies, from the year 1997. They also gave performances

with famous orchestras, such as the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the

London Philharmonic Orchestra, under the direction of Sir Andrew Davis

and Kent Nagano.

The Hilliard Ensemble were guests at all major

British festivals, such as Bath, Cheltenham, Aldeburgh, Norwich, at the

London Proms and the City of London Festival. Today, they perform on all

of the world's major stages. The Hilliard Ensemble also participated at

the Berliner Festwochen, the Ludwigsburger Schlossfestspiele, the

Schleswig-Holstein music festival, the `Tage alter Musik' in Bonn, the

MDR Musiksommer, the Bach-Fest in Leipzig, the Bregenzer Festspiele, the

Salzburger Festspiele and the festival in Aix-en-Provence.

In

the autumn of 2001, Morimur, the product of a successful collaboration

with German violinist and Baroque expert, Christoph Poppen, was

published. 2002 saw the première of The Pear Tree of Nicostratus, by

Piers Hellawell, with the Ostrobothnian Chamber Orchestra, in Kaustinen,

Finnland. In 2002, inpetto filmproduktion produced a film portrait of

the Hilliard Ensemble for ZDF/ ARTE. September 2003 saw the first

performance of Stephen Hartke's Symphony No. 3, based on old Anglo-Saxon

texts with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, which was

enthusiastically received by the public and the press.

Thy kiss of a divine nature

is a high-tech pleasure to the senses, which allows today's listener to

appreciate the artistry of medieval music. The audiovisual

implementation of this documentary in cinematic format was a complex

process, produced by Uli Aumüller's inpetto filmproduktion, as well as

various other partners. The film was co-produced by Bewegte Bilder

Medien AG, Cinegate GmbH , Digital Images GmbH, Bayrisches Fernsehen and

ARTE. The material included analogue standard photography,

high-resolution digital photography, steadicam journeys through a wood

at dawn, time lapse photography of light adaptations in a church, a 60

metre long dolly track journey through the nave of Laon Cathedral, and

blue screen recordings of the two dancers, all of which were used for

projections with video and large screen projectors in the church in

Lübeck.

In 2002, two years before the start of the shooting, the

director and author of the film project, Thy Kiss of a Divine Nature —

The Contemporary Perotin, wrote an essay — an interview with himself,

where he talks about his vision of the film project in a detailed and

imaginative way. This text became an exposé of sound, which contributed

crucially to the financing of the film project — Ulrich Ritter spoke the

part of the director, while the director himself only asked questions.

In 2005, one and a half years after the end of shooting, Stefan

Gagstetter and Uli Aumüller began to illustrate this interview using the

project's copious archive material, and to compose a new video track to

the existing sound track. The result was a two-voice sound-image fugue,

where the voices are simultaneously independent and intertwined,

similar to Perotin's polyphonic music. The third part of this DVD

production shows the unabridged symposion of the four scholars Martin

Burckhardt, Rudolf Flotzinger, Christian Kaden and Jürg Stenzl, which

was recorded on 13/03/2003 in the choir stalls of Schleswig Cathedral.

This conversation, which is reproduced in excerpts in the cinema version

of the film, shows how scientists approach the phenomenon of the Middle

Ages in various ways. In a virtuoso manner and with great passion,

these four men discuss the contemporary nature of the composer, whose

historical existence, as mentioned above, is in doubt. This mere

biographical happenstance, however, does nothing to lessen the beauty of

his music. And although these four scientists are faced with insoluble

problems, the musical genius of this medieval composer, despite their

differences of opinion, is undisputed even for them.

Digital

Images (digim) were responsible for the complete post production process

of the film project, including the conception, adaptation and

digitalisation of both DVDs, and the CD. With close to 1500 DVD

productions to date, this Halle-based company belong amongst the world

market leaders in classical DVD productions. From approximately 200 DVDs

produced internationally every year in the fields of classical music,

ballet and opera, 170 of these are mastered by digim, in Halle. They

create high end productions for Arthaus Musik, Bel Air Classique,

Euroarts, TDK, Deutsche Grammophon, about the content of the film also

applies and EMI, amongst others. to the quality of the DVD: "And it

turns The postproduction of the film material out that the Middle Ages

as a whole, and for Thy Kiss of a Divine Nature included Perotin's music

in particular, were surdrawing up sound and image logs, colour

prisingly modern."