medieval.org

Sony Vivarte 45860

1990

medieval.org

Sony Vivarte 45860

1990

MASS I - SANCTUS

Cantus firmus: Motive A

01 - Sanctus

[2:33]

02 - Pleni sunt caeli [1:27]

03 - Osanna [1:34]

04 - Benedictus [1:41]

05 - Osanna [1:28]

Motivic development:

a. Step-wise development of the original motives up to the fourth above

b. Retrograde of a.

MASS II - CREDO

Cantus firmus: Motive B

06 - Patrem

omnipotentem [4:06]

07 - Crucifixus [3:41]

08 - Et unam sanctam [1:31]

Motivic development:

a. Motive in the original form

b. Retrograde and inversion of a.

c. Inversion of a. (= Retrograde of b.)

d. Retrograde of a. (= Inversion of b.) (= Inversion and Retrograde of

c.)

MASS III - KYRIE

Cantus firmus: Motive C

09 - Kyrie summe

Pater [2:49]

10 - Christe timende Deus [2:02]

11 - Kyrie vivificum [1:17]

Motivic development:

a. Motive in the original form

b. Retrograde of a.

c. Transposition of a. to the fourth above

d. Retrograde of c. (= Transposition of b. to the fifth below)

e. Transposition of a. to the second above (= Transposition of c. to

the fifth below)

MASS IV - SANCTUS

Cantus firmus: Motive D

12 - Sanctus

[2:46]

13 - Pleni sunt caeli [2:04]

14 - Osanna [1:25]

15 - Benedictus [1:38]

16 - Osanna [1:26]

Motivic development:

a. Motive in the original form

b. Retrograde of a.

c. Transposition of a. to the fourth below

d. Retrograde of c. (= Transposition of b. to the fourth below)

MASS V - CREDO

Cantus firmus: Motive E

17 - Patrem

omnipotentem [3:05]

18 - Crucifixus [1:51]

19 - Confiteor [1:33]

AGNUS DEI

20 - Agnus Dei I

[3:26]

21 - Agnus Dei II [1:47]

22 - Agnus Dei III [3:27]

Motivic development:

a. Motive in the original form

b. Retrograde of a. in the fifth below

c. Transposition of a. to the fifth below (= Retrograde of b.)

d. Retrograde of a. (= Transposition of b. to the fifth above) (=

Retrograde of c. in the fifth above)

MASS VI - CREDO

Cantus firmus: L'homme armé complete in the original form

23 - Patrem

omnipotentem [3:38]

24 - Crucifixus [4:08]

25 - Confiteor [2:18]

Thematic development:

Canonic treatment in the fifth below

Huelgas Ensemble

Paul van Nevel

Anne Mertens, cantus

Marie-ClaudeVallin, cantus

Katelijne van Laethem, cantus

Hans Latour, countertenor altus

Josep Cabré, countertenor bassus

Bart Coen, soprano, alto and bass (C, F) recorders

Peter de Clerq, tenor (C) and Bass (F) recorders

René van Laeken, fiddle, rebec, tenor bombardon, tenor dulcian

Symen van MeEchelen, alto sackbut

Sabine Weill, shawm

Schola:

Jean-Yves Guerry, Katelijne van Laethem, Anne Mertens, Nelen Minten,

Marie-ClaudeVallin, Godfried van de Vyvere

recorded: October 1989

Chapel of the Irish College, Leuven

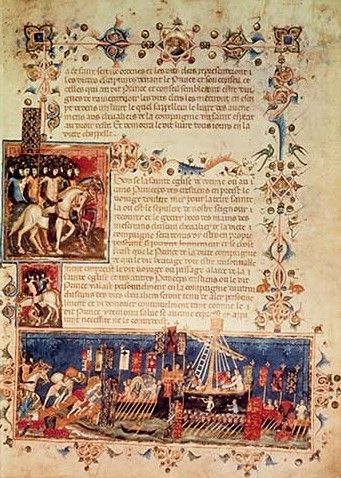

LA DISSECTION D'UN HOMME ARMÉ

The Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples possesses one of the most

remarkable manuscripts of the early Renaissance. The manuscript

catalogued VI E 40 contains a cycle of six masses, all based on the

Burgundian song "L'homme armé", which was very popular in

both the musical and political circles of its day. Each mass contains

the five sections of the Ordinary of the Mass (Kyrie, Gloria, Credo,

Sanctus and Agnus Dei), bringing the total of movements in the entire

compositional cycle to thirty.

The first five masses are written in four parts; the sixth, however, is

composed for five parts, due to the presentation of the cantus

firmus as a two-voiced canon. All the masses contain short passages

for two or three parts without cantus firmus, as well. That is

the case in some middle sections, for example, in the second Agnus Dei

invocation or in the Benedictus. Moreover, all the Kyrie sections are

troped.

This repertoire is unique for a number of reasons. The entire

compositional cycle is grouped around a central theme: the song "L'homme

armé". There exists no other music manuscript that

demonstrates a musical cohesion drawn from one single idea in this way.

For this reason, the Burgundian manuscript with its cycle of thirty

movements is to be considered a unified musical entity. This unity is

emphasized in the outward appearance of the manuscript, as well. Text

and music are presented uniformly in the entire manuscript; so, for

example, throughout the thirty movements of the cycle, those sections

without a cantus firmus are all written in red ink; those

sections with a cantus firmus all appear in black ink. Here the

red color does not, as is otherwise customary, have a specifically

rhythmic significance (as a color), but merely serves to mark

the difference between those passages lacking a cantus firmus

and those containing one. This method of writing is pursued so

consistently, that one note belonging to a cantus firmus

section is written in black ink, while the dot after the note (punctus

additionis) is written in red, when the note is to be held longer

than the last note of the cantus firmus.

Another distinctive feature of this cycle is the diversity and high

quality of the contrapuntal writing. Although the compositions were

handed down anonymously, the influence of two composers is easily and

clearly discernible: of Dufay and above all, of Busnois.

The most prominent characteristic of this mass cycle is however the

treatment of the cantus firmus "L'homme armé";

this accounts for the exceptional position this collection occupies in

the repertoire of 15th-century music. The cantus firmus of each

mass in this collection is drawn from a different section of the "L'homme

armé" melody. The sixth mass represents the culmination of

this treatment, as the entire melody of the cantus firmus

appears in the form of a two-voiced canon at the lower fifth. The cantus

firmus always appears in the tenor part and according to

instructions in the manuscript, is to be performed instrumentally.

The thematic integration of the six masses using portions of the melody

of the song "L'homme armé" is merely the point of

departure for a most effortless treatment of the theme fragments. In

each mass, the thematic material of the cantus firmus is

transformed rhythmically and melodically. In addition to the original

form, the theme is presented in inversion, retrograde, diminution,

augmentation, transposition, with change of ligature and in various

combinations of these techniques - truly a diverse treatment of the

basic material.

Although the nature and extensiveness of this Neopolitan manuscript

makes it unique, the use of a secular melody as a cantus firmus

for a mass composition was nevertheless common practice in the 15th

century. The song "L'homme armé" was apparently very

popular in this context: in the space of somewhat more than a century

(ca. 1465-1580), no fewer than 35 masses based on this theme were

written.

The song, it is clear, originated in Burgundian court circles. The

exact date cannot be determined conclusively; it is probable that the

song appeared shortly before the mass cycle was composed - that is,

between 1450 and 1463. The song's composer is unknown, although the

Italian music theoretician Pietro Aron (ca. 1480-1545) attributed its

authorship to Anthoine Busnois. Busnois served at the court of Charles

the Bold (1433-1477), even before the latter became Duke of Burgundy.

The text is:

L'homme, l'homme, l'homme armé, l'homme armé,

L'homme armé doibt on doubter, doibt on doubter.

On a fait partout crier,

Que chascun se viegne armer d'un haubregon de fer.

L'homme, l'homme, l'homme armé, l'homme armé,

L'homme armé doibt on doubter.

(The armed man must be feared; everywhere it has been decreed that

every man should arm himself with an iron coat of mail; the armed man

must be feared.)

The tone of the text is militantly political, the melody of the song

pugnacious in character. The prominent use of fourth, fifth and octave

leaps and the sharply accented rhythm of the melody emphasize this

character.

The fact that polyphonic compositions based on "L'homme armé"

were so successful during the reign of Charles the Bold can be well

understood when one regards the context more closely.

If the fearsome figure "L'homme armé" was meant to

portray a person who really existed, then this must be Charles the Bold

himself, who spent a great deal of his life waging war and who in the

end found his death on the battlefield. The chronicler Olivier de la

Marche commented on the latter event: "[...] it was his desire and his

passion to wage war against the unbelievers himself; he wanted to

attain greatness and power in order to become a ruler and a leader of

other people, for he never wanted to subjugate himself to anyone else

[...]". A song with a text that contains symbolic allusions to a feared

person had to flatter the vanity of such a person.

Yet there are further reasons for the success of this song. As de la

Marche's reference to the "unbelievers" indicates, military conflicts

of this age had, for the most part, religious origins. Even earlier

Burgundian leaders were concerned in their political actions with

stopping the spread of the Islamic religion, represented in the

military advances of the Turks. For this reason, even plans for a

Crusade were drawn up, but not carried out. After the Turks had

conquered Constantinople in 1453, Charles the Bold also decided to

develop strategies to stem the tide of the Turks' advance. In this

context he sought assistance from the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus

(1457-1490) and at the court of Naples. In this context it should be

mentioned that the mass cycle was dedicated to Beatrice of Aragon, who

was not only the daughter of Ferdinand I of Naples, but who also

married the Hungarian king in 1476. It is not surprising that in an age

of political and religious tension and conflicts a song like "L'homme

armé" should be received enthusiastically.

There are sufficient reasons to support the thesis that mass cycles,

beyond their liturgical function, also contained a political and

ideological message. Whether the cycle of masses was commissioned by

Burgundian princes or whether its composer (or composers) compiled it

from freely-composed pieces, is an unimportant question. The

tightly-woven texture of noble polyphony in connection with a cantus

firmus of such obvious political origin serves in and of itself to

clearly express the composer's political intentions. The use of the "L'homme

armé" melody as a cantus firmus affirms not only the

political but also the religious victory over the "unbelievers". A

military idea is cloaked in liturgical attire and thus presented to the

faithful.

The following details show that here, the mass composition served as

the pretext for a most artful polyphonic treatment of a subject and

also that non-liturgical factors played an important role in the

composition:

1. Measured by Burgundian standards, the texting of the music is

noticeably incomplete and sloppy.

2. The only text that is completely and unmistakably presented in the

score is the text to "L'homme armé", in each of the six

masses.

3. The Latin instructions for the performance of the cantus firmus

make constant reference to the protagonist of the song "L'homme

armé". It is never said, the cantus firmus is to be

performed in this or that manner, but that "the armed man" should do

this or that: "Ambulat hic armatus homo, verso quoque vultu Arma rapit

[...]".

4. The mass text is divided up among different sections of the music,

without regard to its normal contextual meaning. For example: in the

Gloria one musical section already ends after "tu solus sanctus". The

complementary phrase "tu solus dominus" only appears in a later musical

passage.

5. The instructions for the instrumental performance of the tenor

contradict the otherwise purely vocal setting of the masses.

The mass cycle "L'homme armé" represents one of a number

of examples of typical 15-century thinking. The strict separation of

the sacred and the secular, of ecclesiastical and political matters,

was foreign to Burgundian thinking. It is precisely this inseparable

fusion of two 15th-century worlds that holds the key to the fascination

of the recording here. Or, to use the words of J. Huizinga in his book Autumn

of the Middle Ages: "The permanent contrast and the variegated

forms exhibited by all things permeating the human spirit was the

source of a stimulus to the people of that age, originating in everyday

life - a passionate power of suggestion, revealing itself in a

fluctuating mood of raw emotions, severe cruelty and ardent compassion

[...]."

Paul van Nevel

(Translation: Deborah Hochgesang)