In morte di Madonna Laura / Huelgas Ensemble

Madrigal cycle after texts of Petrarca

medieval.org

Sony Vivarte 45942

1991

1.

1 - [6:03]

1a. Canzoniere No.267

Spirito l'Hoste da REGGIO (c.1510-c.1575). Oimè il bel viso

1b. Canzoniere No. 283

Spirito l'Hoste da REGGIO. Discolorato hai, Morte, il più bel volto

2. Canzoniere No. 268

2a. [stanza 1 + 2]

2. Padre F. Mauro de'SERVI (c.1545-c.1621). Che debb'io far - Amor

tu'l senti [5:49]

2b. [stanza 1 + commiato]

3. Bernardo PISANO (1490-1548). Che debb'io far - Fuggi'l sereno

[4:39]

2c. [commiato]

4. Tomaso CIMELLO (c.1500-c.1580). Fuggi'l sereno [2:55]

3. Canzoniere No.353

5. Stefano ROSSETTI (c.1520-c.1585). Vago augelletto che cantando vai

[5:15]

4. Canzoniere No. 282

6. Baldassare DONATO (c.1530-1603). Alma felice che sovente torni

[5:41]

5. "Mia benigna fortuna" (Canzoniere No. 332)

5a. [stanza 2]

7 . Padre F. Mauro de'SERVI. Crudele, acerba, inexorabil Morte

[4:19]

5a. [stanza 10]

8. Cesare TUDINO (c.1530-c.1590). Amor, i'ho molti e molt'anni pianto

[5:07]

5a. [stanza 7]

9. Spirito l'Hoste da REGGIO. Nessun visse già mai

più di me lieto [7:00]

6. Canzoniere No. 365

6a

10. Padre F. Mauro de'SERVI. Io vo piangendo i miei passati tempi [4:58]

6b

11. Andrea ROTA (1553-1597). Io vo piangendo i miei passati tempi

[4:16]

7. Canzoniere No. 246

12. Nicola VICENTINO (1511-c.1576). L'aura che'l verde lauro

[6:12]

Huelgas Ensemble

Paul van Nevel

Katelijne van Laethem, Cantus

Ibo van Ingen, Tenorino

John Dudley, Tenor

Josep Cabré, Baritone

Lieven de Roo, Bass

Johannes Boer, Tenor Viola da gamba - R. Passaro, Belgium

(Italian Renaissance)

Gail Ann Schroeder, Bass Viola da gamba - M. Ternovec, Italy

(after Gasparo da Salò)

Piet Stryckers, Bass Viola da gamba - R. Passaro, Belgium

(Italian Renaissance)

Willem Bremer, Cornetto - J. van der Veen

Bass Curtal - Eric A. Moulder

Recorder, Bass Recorder - E. G. Morgan/Hopf

Bart Coen, Alto and Basso Recorders - Koblicheck, Bergström

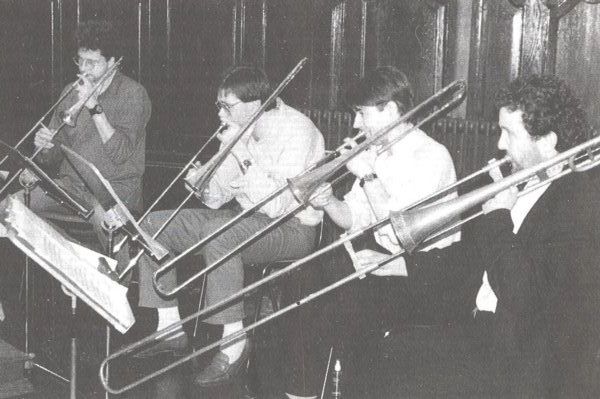

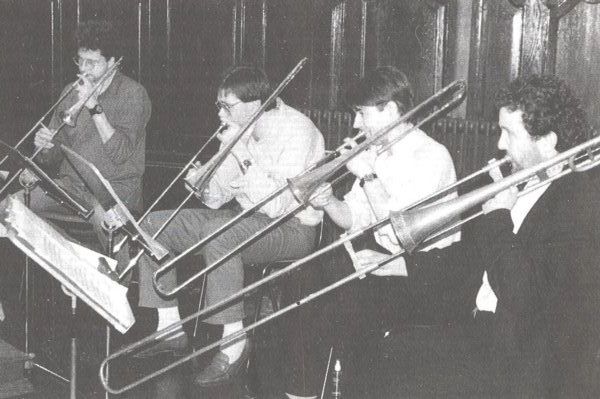

René van Laken - Tenor Curtal - Eric Moulder, London 1984

Harry Ries - Alto Saqueboute - H. Glasl, 1989

Wim Becu - Bass Saqueboute - Meinl & Lauber, 1978

Producer / Recording Supervision: Wolf Erichson

Recording Engineer / Editing: Stephan Schellmann (Tritonus)

Recording place: Chapel of the Paridaens Intituut, Leuven (Belgium)

February 23-25, 1990

Cover Design: CC. Garbers / B. Kruck

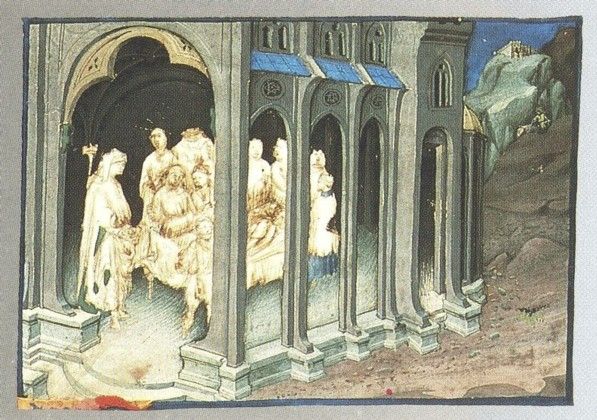

Cover Front: Book Miniature from Petrarca's 264th Chant (Bologna),

Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin

℗ Sony Classical GmbH

© Sony Classical GmbH

PETRARCA AND HIS

CANZONIERE

Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), one of the greatest

poets and Humanists that Italy has ever produced, was, to say the

least, a most controversial figure. He was a Humanist, poet, diplomatic

emissary, great traveller, author of pamphlets, translator, lively

letter-writer and a person with a critical eye for the ins and outs of

society.

Petrarca's activities in life centered around three

geographical areas. The first of these was Avignon, a city he

frequently visited. He was especially drawn to Fontaine de Vaucluse, a

village nearby, where he spent long periods meditating, writing and

working on new projects. The second pole to which Petrarca felt

attracted was the city of Rome, which he visited for the first time in

1337. Petrarca was to regard the eternal city as the center of Western

society for the rest of his life. The third area where Petrarca spent a

great deal of time was northern Italy, where he travelled through or

stayed in cities such as Verona, Bologna, Venice, Padua, Parma and in

particular, Milan, where he was associated with the court of Galeazzo

Visconti.

But of course Petrarca also travelled outside of

these areas as well; in 1333 he travelled to Paris, Gent, Cologne and

Liège, where he is said to have re-discovered the speeches of

Cicero. In 1343 we find Francesco in Naples, on a diplomatic mission;

in 1355 he visited Paris and in 1356, Prague.

The vast majority of his œuvre is written in

Latin. Petrarca thought in Latin; it was his "working language".

Petrarca's most important contribution to Italian poetry is his

collection of poems known as the Canzoniere. This collection

made him more famous than all his Latin works combined. The Canzoniere

originated due to an event which affected him emotionally for the rest

of his life. It was his fleeting acquaintance with a beautiful woman,

Laura de Noves, whom he met on the 6th of April, 1327 in the Church of

St. Claire in Avignon. This meeting was to play a crucial role in

Petrarca's life, both as a poet and as an artist. His - under the

circumstances - platonic love for Laura finds its expression in the

poetry of the Canzoniere. His lovesick state is incurable and

his feelings received a new impulse in 1349, when he heard of Laura's

death. He then began to give the poems he had already written a more

definite structure, augmenting these with new poems and giving the Canzoniere

its present organization. In 1367, he gave the collection the

definitive title of Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta. The Italian

madrigalists of the sixteenth century regarded these verses to be the

most exemplary form of Italian poetry ever created.

The Canzoniere collection consists of 366

poems Petrarca wrote from 1327 onwards and is divided into two parts:

the first part, In Vita di Madonna Laura, contains 263 poems

and was written before Laura's death; the second part, In Morte di

Madonna Laura, contains 103 poems, all dedicated to Francesco's

mourning and to the memory of Laura. It is typical of Petrarca that he

writes as much about himself as he does about his lost love. In many of

his poems, Petrarca opens up his soul to the reader, making masterly

analyses of his inner life and of his doubts. In Morte di Madonna

Laura depicts countless shades of the emotions of one man, from

sublime memories to inconsolable despair. A kind of musical fluidity

arises from Petrarca's careful and flexible use of elisions, and

through the almost inexhaustible richness of his metrical

constructions. His style is characterized by an abundant use of

rhetorical figures; the antithesis in particular can be considered the

hallmark of Petrarca's language.

Its richness of sound and rhythmic virtuosity,

coupled with its luxuriant imagery must have made Petrarca's work

appealing to the Italian madrigalists of the sixteenth century.

Petrarca, who himself sang and played a plucked instrument, clearly had

no high opinion of Italian minstrels. In a letter to his friend

Boccaccio, he wrote that Italian musicians possessed "no great voices,

but long memories, great diligence and even greater shamelessness".

In the sixteenth century, a great interest in

Petrarca's poetry arose; no composer failed to set his texts to music:

All the poems contained in the Canzoniere were set to music at

least once, more often by various composers in several versions. Two

reasons can be given for this sixteenth century "fashion": first,

Humanism was attaining growing importance and this led to a demand for

good texts, especially in the composition of madrigals - composers

found in Petrarca's poetry just the emotional tone and rhythmical

variety they were seeking for these works. Second, the rise of

Petrarchism in the sixteenth century also contributed to an increasing

interest in his works in musical circles. The foremost supporter of

Petrarca was Pietro Bembo (1470-1547) who termed Petrarca's Canzoniere

an exemplary work for all Italians in his "Prose della volgar lingua",

declaring Tuscan to be the superior Italian language. Bembo published

the Canzoniere in 1501; in the course of the sixteenth century,

more than 130 editions of this work appeared in Italy.

It is against this background that we would like to

place the "musical Petrarchism" evidenced in the works of the best

Italian composers of Petrarca's texts. In the case of the sometimes

little-known Italian composers we have chosen for this recording, their

rendering of the expressive and emotional content of Petrarca's texts

makes them the (unrecognized) leaders in expressing Petrarch's art.

Paul van Nevel

Spirito l'Hoste da Reggio (c. 1510-c. 1575; period of artistic

activity: 1545-1560), born in Flanders, went to Italy, as did many of

his countrymen, due to the greater possibilities Italy offered in terms

of artistic fulfillment as a composer. The first madrigal on this

recording, with its repeated motive of lament in the upper voice, was

drawn from his first volume of madrigals, published in 1547.

Padre F. Mauro de'Servi (c. 15451621), like his contemporary

Andrea Rota (1553-1597), was active in Bologna. The compositions he

wrote there not only demonstrate the conventional compositional

rendering of the text typical of his day (that is, madrigalisms) but

also reveal Servi's attempts to convey even subtle nuances in the

poetic language.

Stefano Rossetti (c. 1520-c. 1585; period of artistic activity:

1560-1580), active at the Cathedral of Florence about mid-century, is

considered the originator of the "madrigale arioso": the texts of his

compositions are not interpreted musically so much by harmonic means as

by a very vivid rendering using elaborate embellishments in the vocal

line.

Bernardo Pisano (1490-1548), the oldest composer in this cycle,

writes in a contrapuntally stricter style than the others. The

sometimes surprising cadential formulas of this composer, who was also

a singer at the papal chapel in Rome, foreshadow the bold harmonic

practices of the later, "true" madrigalists.

Tomaso Cimello (c. 1500-post 1579) treats text and music in his

madrigals as elements of nearly equal importance: not only does he

carefully note the author of each text, but he also takes individual

lines of the poems of several authors as the basis for some of his

compositions. In this recording, however, one gains the impression that

the text is more important than the music.

Baldassare Donato (between 1525 and 1530-1603) was the court

music director at the Cathedral of St. Mark in Venice from 1562 to

1565. The counterpoint and pleasing sonoric quality of his compositions

reveal quite clearly the influence of his contemporaries and friends

Adrian Willaert and Cipriano de Rore.

Cesare Tudino (c. 1530-c. 1590) is represented on this recording

by a madrigal taken from his first volume of madrigals, published in

1554. The bold chromaticism and the daring treatment of dissonances in

this work reveal him as a very progressive composer of this period.

Nicola Vicentino (1511-1576) caused a great sensation among his

contemporaries through his attempts to explore extensively the harmonic

possibilities of the tonal system of his day, creating amazing sonoric

effects in his music. His innovations in the compositional sphere,

however, in no way affect the form and construction of the texts he set

to music, in this case a poem by Petrarca.

Translation: Deborah Hochgesang