Guillaume de MACHAUT. Virelais, ballades et rondeaux

Mon chant vous envoy

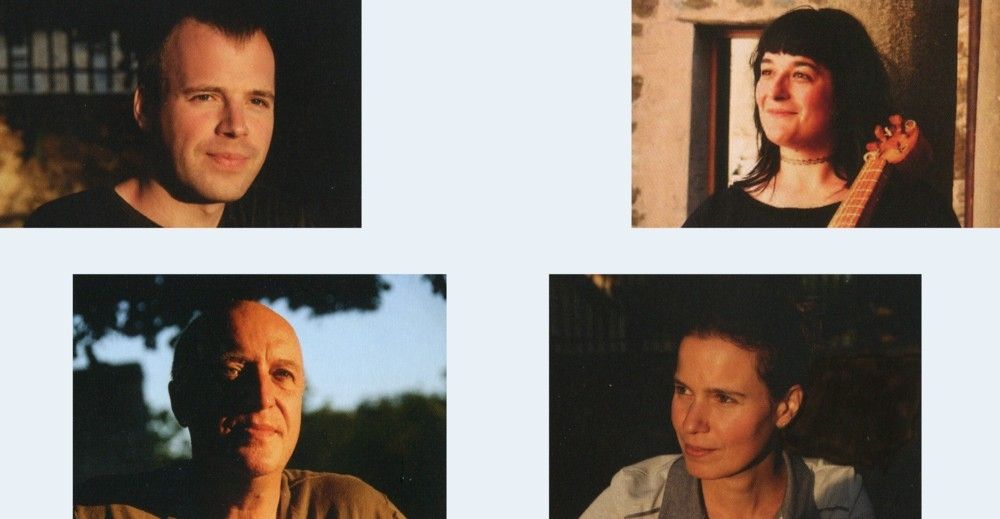

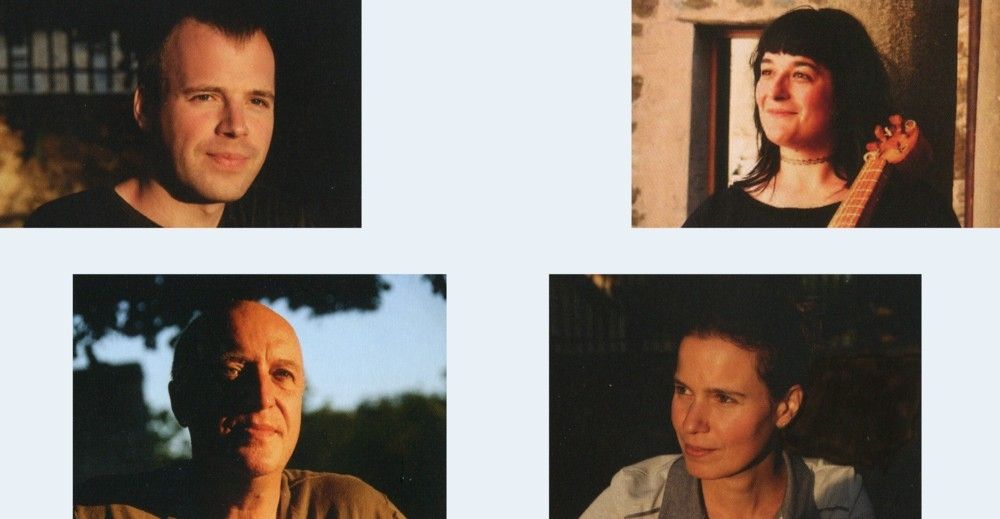

Marc Mauillon, Angélique Mauillon, Vivabiancaluna Biffi, Pierre Hamon

Eloquentia 1342

2012

virelai

1. Quant je suis mis au retour

[2:47]

MM, PH, MG, harpe, vièle, frestel, luth

virelai

2. Comment qu'à moy lonteinne

[4:42]

MM, AM, VB, harpe, vièle, flûte double, luth, organetto

rondeau

3. Puisqu'en oubli suis de vous, dous amis

[2:06]

AM, VB, MM

ballade

4. J'aim mieux languir [2:38]

harpe

ballade

5. Plourez, dames, plourez vostre servant

[7:32]

MM, VB, vièle

virelai

6. Dou mal qui m'a longuement

[4:12]

MM, harpe, ceterina

rondeau

7. Dix et sept, cinq, trese, quatorse et

quinse [3:35]

MM, VB, harpe

virelai

8. Dame, vostre ous viaire

[6:06]

MM, harpe, vièle, flûte traversière

ballade

9. Phyton, le mervilleus serpent

[6:13]

MM, vièle, harpe

ballade

10. Amours me fait désirer (texte)

[2:16]

MM (voix récitée), luth

ballade

11. Amours me fait désirer

[4:41]

VB, vièle, flûte à bec

virelai

12. Se ma dame m'a guerpi

[4:36]

MM, flûte traversière

13. Et musique est une science

[1:14]

organetto

prologue

14. Loyauté weil tous jours

[0:42]

MM · voix parlée

virelai

15. Liement me déport

[5:39]

harpe, vièle, ceterina, organetto, flûtes à

trois trous et tambour, tambourin

virelai

16. J'aim sans penser laidure

[2:11]

MM, vièle, harpe, luth, flûtes à trois trous et

tambour, organetto, tambourin

Marc Mauillon, voix MM—1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14,

16

Vivabiancaluna Biffi, voix VB—2, 3, 7, 11, et vièle—1,

2, 8, 9, 11, 15, 16

Angélique Mauillon, harpe—1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8,

9, 15, 16 et voix AM—2, 3

Pierre Hamon, flûte médiéval à bec—11,

flûte médiéval traversière—8,

12,

flûte double—2, flûtes à trois

trous et tambour—15, 16, frestel—1, voix

PH—1, et

direction musicale

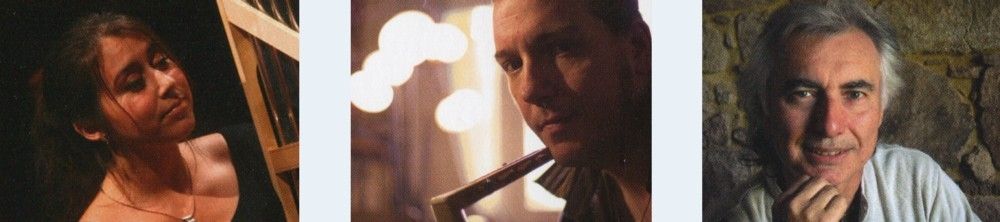

Michaël Grébil, luth—1, 2, 6, 10, 16, ceterina—6,

15 et voix MG—1

Catalina Vicens, organetto—2, 13, 15, 16

Carlo Rizzo, tambourin—15, 16

Recorded in july 2012 at the Fondation Laborie en Limousin, Limoges, France

Producer engineer & editing: Laurence Heym

Liner notes by Elizabeth Eva Leach & Pierre Hamon

Translation by Doriane Heym (Franšais) & Mary Pardoe (English)

Cover photo @ Doriane Heym

'How is it that more than seven hundred years later these sequences

of notes can have such an impact? This is a mystery to me. Although the

original lyrics often seem overwrought, the music is extraordinarily

fresh. The melodies and harmonies are far from today's classical music

conventions, yet they speak even more directly and profoundly'.

Robert Sadin

in the introduction to the magnificent album 'Art of Love: Music of

Machaut' (Robert Sadin, with an extraordinary array of contemporary

artists, including Mark Feldman, Hassan Hakmoun, John Ellis, Madeleine

Peyroux, Nathalie Merchant, Lionel Loueke, Brad Mehldau, Milton

Nascimento, Cyro Baptista); Deutsche Grammophon, 2010.

Ce mystère «Machaut», qui ne cesse de nous fasciner

également, nous a incités, dans nos deux

précédents enregistrements, L'Amoureus tourment

et Le Remède de Fortune, à l'exploration de

formes longues comme le lai et la complainte, où la

poésie et la musique naturelle des mots nous ont convaincus de

l'importance de donner à entendre ces œuvres dans leur

intégralité, la poésie étant en constant

dialogue avec la mélodie, l'une éclairant l'autre.

S'il est vrai que Guillaume de Machaut appelle lui-même vieille

et nouvelle forge les anciennes et nouvelles manières de

composer, notre intuition est que la modernité du chanoine de

Reims n'est peut-être pas là où on l'attend

généralement - à savoir, dans un avant-gardisme du

contrepoint et de la polyphonie et dans la complexité de son

écriture. Sa véritable «modernité», ou

plutôt son humanité dans les émotions, les

questions qu'il pose sur la vie, l'amour, la création

artistique, se révèle peut-être encore mieux dans

ses chansons.

Guillaume de Machaut, célébré en son temps

à la fois comme le plus grand poète et le plus grand

compositeur français du XlVe siècle, a malheureusement,

par un revers de fortune, souffert de ce double statut qu'il est le

dernier à posséder. Lors de sa redécouverte au

XIXe siècle, puis au cours du XXe siècle, «le

dernier trouvère» a été analysé et

étudié comme poète dans les cercles

littéraires, bien sûr inaptes à considérer

sa musique, ou comme compositeur extrêmement savant par les

musicologues et compositeurs d'avant-garde, fascinés par sa

science du contrepoint. Un intérêt initial

disproportionné (selon les termes de la musicologue Elizabeth

Eva Leach, qui nous a fait l'honneur d'écrire la

présentation de ce disque) pour sa Messe, ainsi que pour les

structures rythmiques complexes de ses motets, où la

présence simultanée de plusieurs textes, et donc la

difficulté de saisir et d'entendre clairement la poésie,

a contribué á faire attribuer la

célébrité de Machaut d'abord à sa

virtuosité de compositeur, et à fausser son image.

Certes, notre univers culturel est très éloigné de

celui de Machaut, qui a pour références Boèce, la

mythologie antique, le Roman de la rose, etc. Mais, comme aujourd'hui,

le XlVe siècle est une époque inquiète

bouleversée par de grandes catastrophes (grande peste),

instable, avec, dans les arts vivants, le passage de l'oralité

au livre - plus qu'aucun autre, Machaut y est particulièrement

sensible, lui qui veille lui-même à la facture et à

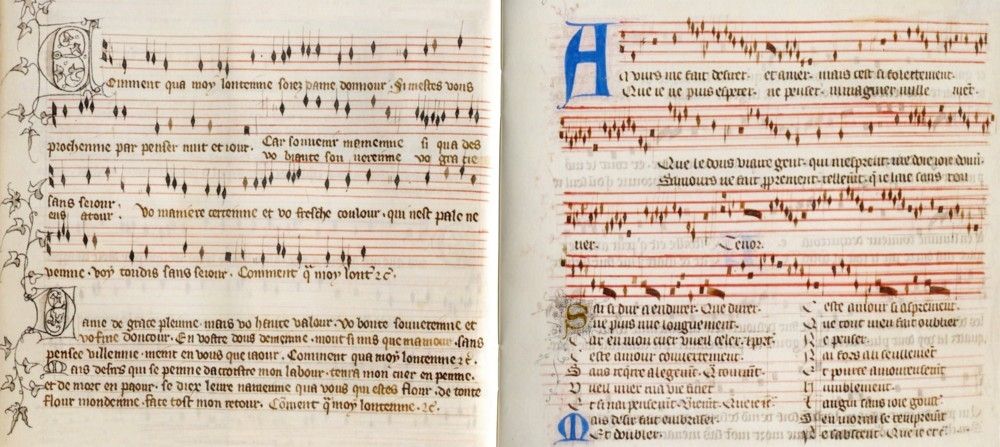

l'enluminure de ses manuscrits. C'est une époque où le

livre est un nouveau média. On peut le lire publiquement ou dans

l'intimité de la chambre, admirer ses enluminures, en extraire,

pour le chanter, un lai, une ballade ou un virelai, danser sur ce

dernier, ou encore tout simplement lire les poèmes à voix

haute ou en silence, mentalement - ce qui est par ailleurs une pratique

encore récente au XlVe siècle.

Nous sommes convaincus de l'intemporalité de ces œuvres,

et en particulier de ces petites «chansons

balladées». Ce qui nous touche aujourd'hui, en

écoutant et en chantant Machaut, c'est peut-être, avant

tout, le pouvoir de consolation de la musique, qui agit sur l'âme

du poète, dont les paroles s'avèrent étonnamment

proches de notre sensibilité. La musique réchauffe et

«réjouit» un cœur inquiet qui interroge le

destin, les mystères du sort et les tourments de l'amour.

Partout ou elle est, joie y porte;

Les desconfortez reconforte,

Et nes seulement de l'oïr.

Fait elle les gens resjoir.

Pierre Hamon

Guillaume de Machaut (c.1300-1377) was the foremost poet and composer

of fourteenth-century France. He was an extraordinary creative artist,

who by the middle decades of the fourteenth century had already

composed a substantial body of literary and musical works, to which he

added until his death in 1377. His contemporaries recognized him as one

of the greatest writers of his day and his reputation as a poet lasted

for some time after his death, which was commemorated in music and

poetry. He was patronized by royalty and his works were performed and

read throughout Europe. His narrative poems marry clerkly didacticism

with the most fashionable traditions in love poetry, and they develop a

first-person narrative persona that greatly influenced Chaucer,

Froissart, Christine de Pizan, and other vernacular authors. Unlike

those poets, however, he set more than a hundred of his own lyrics to

music, helping to establish the lyrico-musical forms of balade,

rondeau, and virelai, which, by the end of the century, came to be

called the formes fixes. He also wrote expansive polytextual

motets in a fashion pioneered by his contemporary Philippe de Vitry,

which modern musicology calls "ars nova." Machaut's is also the first

surviving polyphonic setting of the cycle of the Mass ordinary that is

known to be by a single composer. In terms of number of lines, his

narrative verse places him among the most prolific poets of his age.

More musical pieces survive by him than are known to be by any other

French composer of this period. His training for being a court

secretary may have been formative in his practice of a distinctly

scribal authorial poetics, which led him to oversee the copying of his

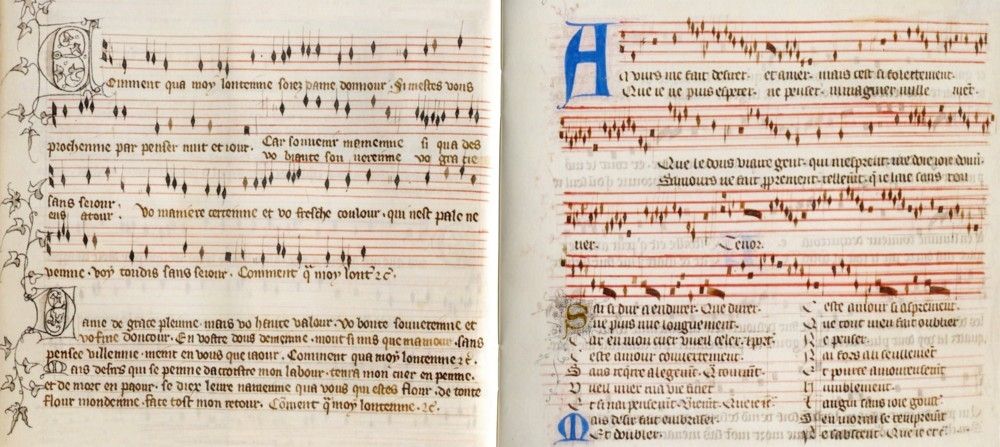

own works: his complete works survive in several large manuscripts from

his lifetime, some of which seem to have been prepared to Machaut's own

specifications. These sources advance the artistic use of the book for

vernacular poetry, making play with mise-en-page, internal

cross-referencing and paratextual features such as indexes and rubrics.

Machaut's works can be seen as the logical conclusion of the troubadour

and trouvère tradition in which scribal reverence for a body of

works has been exercised not by later collectors but by the author

himself. If he didn't invent it, Machaut certainly bolstered and

enshrined the idea of the vernacular author-figure, complete with a

problematic and ironic relationship to his own poetry's truth-value.

For Machaut, written authorship directs both the oral arts: poetry and

music. At no other point in time was a single person so central to the

histories of both European literature and European music in all its

then-current genres.

Despite his reputation and the sizeable body of works that he has left,

the more workaday details that pertain to the man behind the artist are

hard to extract. We have a good number of luxury manuscripts of

Machaut's work, most now available for viewing online (see the list at

http://www.stanford.edu/group/dmstech/cgi-bin/drupal/machautmss). The archival evidence is more

scanty, mostly pertaining to monetary aspects of Machaut's life such as

employment, patronage, taxation, and the receipt of gifts. But a large

number of fairly basic questions remain. The dates of Machaut's birth

and death are unknown. His birthplace, early schooling, training, and

route into the service of his only known employer, King John of

Bohemia, remain obscure, as does the precise employment in which he

engaged after John's death in 1346.

As a poet, Machaut is important but far from unique -- the aspect of

his work that differentiates him from his contemporaries is the central

role of music within his literary output. Machaut was not incidentally

"also a composer" -- his music is not a meaningless ornament to his

lyrics. Instead, as the importance of Orpheus to Machaut's narratives

of desire, love, loss, and mourning shows, his music transforms his

lyric. Music's performative reading of poetry, its links to human

emotion, and its place as a very specific kind of knowledge in medieval

society, allowed Machaut to go beyond his contemporaries in responding

to the needs of his readers for entertaining edification and effective

consolation in the central matters of life, love, and death.

Most of the tracks on this disc are performances of Machaut's virelais,

a genre that Machaut preferred to term chanson baladée ("danced

song"). The form is a simple one, but flexible enough to sustain a wide

variety of verse forms and the music is often monophonic and memorable.

We can imagine the kind of situation described in Machaut's Remede

de Fortune where the lover sings a virelai with his lady and her

courtiers in a round dance on the meadow outside her chateau. Virelais

start with a refrain and then proceed to a pair of verses before

returning to the music of the refrain, but with new words (the

"tierce"). When they hear the familiar music of the refrain with the

tierce text, the courtiers dancing will be in no doubt when the tierce

finishes (because they know the tune), so they know exactly when to

join back in for the refrain again.

The present disc contains a reading from Machaut's so-called Prologue,

a confection of illuminations, lyrics, and narrative poetry which he

wrote late in his life to stand at the head of the manuscript of his

collected works. The Prologue mentions all the genres of song that

follow it in the manuscripts. It can be understood as a statement of

the author's musical poetics designed as a key to his entire output,

specifically discussing the role of emotional

authenticity—sentement—in the creation of musical lyrics.

This emotion can be seen throughout the songs here, especially in

Machaut's Ploures, dames (B32) a kind of auto-testament, in

which the je threatens to die if the ladies of the court don't take

care of him. The music sets the doleful words to jaunty dance-like

triple rhythms, here lacking the joyfulness that they would normally

have as a way of depicting the malady of the singer. Angular lines,

leaps to sharpened notes, and sudden held sonorities all add to the

sense that something is not quite right, while at the same time giving

a warped window onto the ordinarily joyful song that the ladies will be

deprived of if they don't rescue the je from death's door.

Ploures, dames (B32) is one of Machaut's balades, a serious

high-style composition in a direct stylistic descent from the grand

chant of the trouvères. Of the other balades on this disc, the

late Phyton (B38) most clearly shows the seriousness of this lyric

genre, since it draws on the tale of Phiton, the serpent, from the

Ovide moralisé, which it adapts to depict the lady's many-headed

forms of rejection of the je's love. In Amour me fait

desirer (B19) the personified Amours makes the lover desire and

love so that he is unable to hope or think. The poem is here read aloud

as recitation and then performed musically, enabling the listener to

appreciate the additional layers of meaning that the music supplies.

Both "desirer / Et amer" and "esperen / Ne penser" have the same music,

making an aural parallel between the cause of grief (desire) and its

cure (hope). Musically, Love makes the singer "desire" too. The

counterpoint setting the opening word, "Amours," forces the singer to

perform a very unusual melodic interval at the outset of the piece,

from G to c#, offering a strange bisection of the overall G to g octave

range of the first phrase. This c# has contrapuntal "appetite," or

"desire," for resolution to d. Ultimately, Machaut's music becomes the

ultimate surrogate for erotic desire and means of achieving a serene

life.

Elizabeth Eva LEACH