medieval.org

Classico CLASSCD 286

1999

medieval.org

Classico CLASSCD 286

1999

1. Got in vier elementen [2:42]

Meister RUMELANT, Germany 13th century

2. Salterello [5:03] anon. Italy, c. 1400

3. La tierche estampie royal [3:15] Anon. France, c. 1300

4. Christo e nato e humanato [3:47]

From the "Laudario de Cortona", Italy 13th century

Melodic material from the "Cantigas de Santa Maria", Spain 13th century

5. Sabor a Santa Maria [2:53]

CSM 328 +

CSM ? ·

CSM ?

6. Santa Maria loei [4:03]

CSM 200 +

CSM 166 ·

CSM 9

Two ballatas by GHERARDELLUS, Italy c. 1363

7. De' poni amor a me [2:35]

8. I vo bene a chi vol bene a me [2:08]

9. Danse [2:32] anon. France c. 1300

10. From 'Danger me hath, unskylfuly' [3:06] England 13th c.

Untitled instrumental piece from England (Coventry ?) 13th century

11. Douce 139 [1:44]

HILDEGARD von BINGEN, Germany 1098-1179

12. Unde quocumque [4:14]

13. O Euchari [3:45]

Melody from a song of praise to the Danish King Erik Menved by

Meister RUMELANT, Germany 13th century

14. Got in vil hohen vreuden saz [5:02]

Material from melodies collected in the 19th century to the Danish medieval ballad about the talking harp. (DgF 95)

15. Den talende strengeleg [2:39]

A

set of folk tunes from Denmark and the Faroe Islands to the songs

Skon Redselil og hendes moder, Ramun, Det var bolde Hr. Nilaus)

16. Folktunes [4:12]

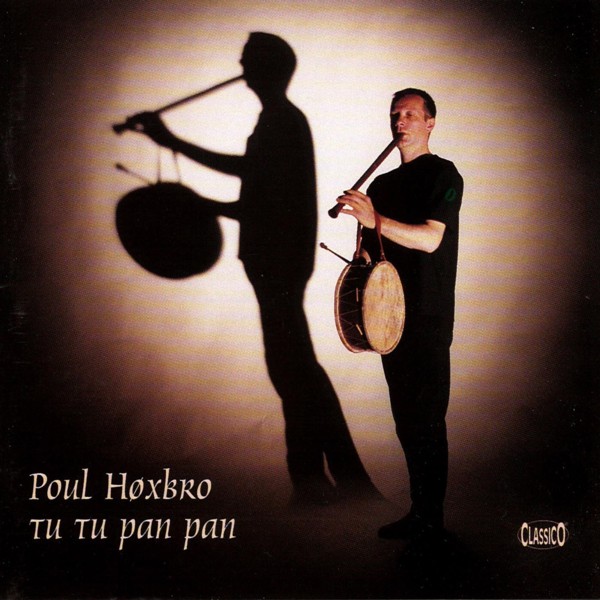

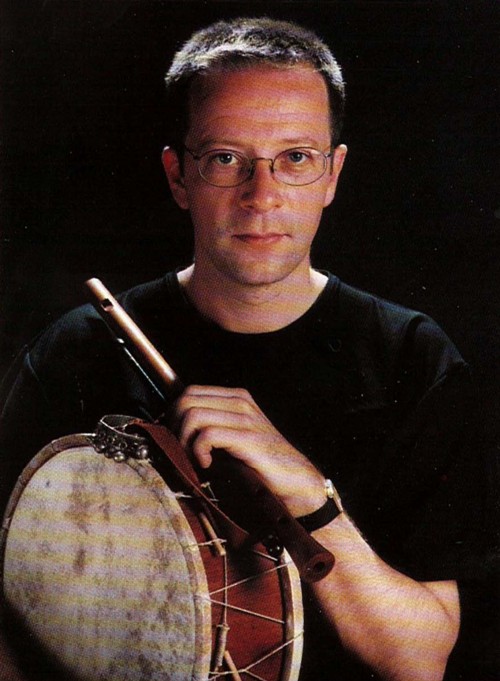

Poul Høxbro

pipe and tabor, pipe and string drum, double pipes

All instrumental renditions and arrangements by Poul Høxbro

Recording: Audiophon Recording Studio, 1999

"...Guy with drum and pipe plays for them this estampie..."

This

line is from a song by the trouvère Jehan Erars (c. 1200 -1259), and it

is one of the first references in existence to the instruments pipe and

tabor being played by one and the same person. The first actual

illustration is found in the El Escorial manuscript of the Spanish king Alfonso the Wise's large collection of Marian songs Cantigas de Santa Maria

from about 1260. When the instrumental combination was conceived

remains uncertain for the time being, but what is certain is that the

combination flourished in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, when it was

prevalent on the whole of the European continent as a more or less

commonly used musical instrument, if literary references and numerous

illustrations are to be considered significant. Of course it can always

be maintained that both words and pictures have been created according

to literary or iconographic models, but if one disregards this rigid

view of historical sources, a completely different picture of the

instrumental combination pipe and tabor emerges from that suggested by

reading books and articles on mediaeval music.

It is quite clear

that there was never any question of the instruments being a musical

curiosity in the Middle Ages. Neither was there any tendency to limit

the use of them to specific musical situations or any unequivocal

association with the Devil - or God for that matter. It is true that the

few Nordic pipe and tabor players we can see illustrated today wear a

fool's costume, and indeed there are many situations involving dancing

which are connected with the instruments, but otherwise the pipe and

tabor crop up quite simply on the same footing as other common

instruments of that time, from the great, symbolic orchestras of angels

to illustrations of everyday music-making, when their function seems to

have been unusually versatile. On the street level it can be seen as an

accompaniment to bear-tamers, acrobats and the chain dances so deplored

by the clergy. At the other end of the scale the pipe and tabor appear

in church processions, at royal wedding ceremonies as well as generally

in small ensembles of angels, when it was often used together with the

harp and rebec.

Between these extremes the instrumental

combination was a common form of entertainment for both high and low,

often as part of a small ensemble of various combinations of the harp,

lute, rebec/fiddle as well as the cornetto. But for the seductive

Moorish dances they were always the only instruments played.

The

pipe and tabor are however also seen in more official situations, for

example as a trio leading an infantry unit or on horseback in a royal

ceremonial procession and providing a background for tournaments and

jousts.

In the Middle Ages it was customary to divide musical

instruments up into two main groups depending on the power of the

instrument in question. The powerful ones like for example trumpets,

horns and shawms were called haut (loud) instruments, and all string instruments, flutes and portatives were called bas

(soft) instruments. The two classes of musical instruments were as a

rule kept clearly apart and did not play in the same ensemble. But here

the pipe and tabor apparently create an interesting exception, since in

the many pictures where they are portrayed they play in one instance

together with the trumpet, shawm and bagpipe, in another with the harp,

lute, psaltery, rebec and fiddle. In the pictures of the large

orchestras of angels or other pictorial allegories in which all

instruments are represented and often divided into the two main groups,

one also sees indications that the pipe and tabor had not achieved a

permanent position in either of the groups, since they seem to have been

classed as loud or soft an equal number of times. In other words it was

an unusually flexible instrumental combination which could be heard in

every conceivable context and perhaps in a far greater part of the

mediaeval tonal conception than former reconstructions of mediaeval

music would seem to suggest.

This was the state of affairs until

the beginning of the 16th century when the pipe and tabor slowly began

to disappear from everyday life and only survived in certain regions.

They are thus specifically mentioned in connection with France, the

Netherlands and England. In the Netherlands they disappeared into

obscurity while in England they were the traditional instruments for Morris Dances

until the beginning of the present century, when the tradition managed

to die out in the space of only a few years, until the instrumental

combination returned to favour in connection with the Morris Dance

tradition. But in the South of France and many places in Spain as well

as in Peru this resourceful oneman-band still plays an important part in

folk music. In the Salamanca province in Spain the pipe and tabor can

still be heard in some churches during the offertory.

And why did this instrumental combination disappear from everyday music-making? In Thoinot Arbeau's dancing treatise Orchesography

from 1589 an explanation almost reminiscent of market economy is

offered, since Arbeau says that in his father's time it was customary to

cut down on expenses by hiring only one musician who played two

instruments at once, while at the present time the lowliest workman

would have both oboes and trombones playing at his wedding. This is

hardly the whole truth and probably not the most important reason. A

more likely explanation is to be found in the relationship between the

specific limitations of the flute played with one hand seen in

connection with modifications of the then prevalent musical language. As

long as music exclusively moved within a modal universe with simple

chromatic adjustments determined by the so-called rules of musica-ficta,

the flute could cope with most demands made upon it, but it failed when

further demands for greater flexibility were made upon it. Neither had

the tendency to increase the range required in written compositions

encouraged the use of the flute, since it was extremely uneven in the

uppermost register. Indeed it was not able to keep up with developments

in art-music, and in this way it was compelled to retire from the scene

and continue an obscure existence as an instrument of the people, so

that in general it had been supplanted by other, more popular

instruments.

The pipe, or flute played with one hand, is a type

of recorder / flageolet with three finger holes. A narrow inner bore

ensures that it is easy to play notes in the harmonic series by

overblowing. In the first octave it is only possible to produce the

first four notes before overblowing to the second octave, but from here

the three holes are sufficient to make it possible to fill out the

intervals between the notes which are overblown and in this way play a

full scale with a compass of at least one and-a-half octaves. There seem

to have been three basic sizes, the middle one tending to be the

favourite, although in the Middle Ages there were probably no actual

standard sizes. However, judging from the dimensions in the vast

majority of pictures, the most common pipe seems to have had a

fundamental somewhere between a and f. In several of the

earliest pictures there is also a pipe which seems to be smaller than

this, whereas especially towards the end of the period in which the pipe

flourished, the upper classes appear to have preferred a somewhat

larger pipe, probably with a fundamental between e and c.

Apart

from this pipe played with one hand the standard version of the

"ensemble" also comprised a tabor. The tabor had parchment on both sides

which was secured by string, making it possible to regulate the

tautness of the skin. In the great majority of cases strings were

stretched over one of the skins, giving a rattling effect each time the

drum was struck. Until well into the 15th century the tabor was always

flat, the diameter (8 - 14 inches?) being greater than the depth, but in

the course of the 15th century and later, there was more often a

tendency to make the tabor deeper than the diameter. And not until the

very latest pictures from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries does the

tabor now and then assume the dimensions which are known from the

Provençal tambourin or the tamboril of Salamanca.

So this is the

standard version of the popular one-man-band. But there were also

exceptions which in the most beautiful possible way justify the modern

musician's desire for experimentation with sounds. In a tapestry from

about 1510 in Musée Royaux et d'Histoire in Brussels an

aristocratic trio consisting of a singer, a clavichord and a large

one-handed pipe is woven into the portrayal. In Palazzo Publico in Sienna, Taddeo di Bartolo (1362-1422) has painted an angel with pipe and triangle, and in Estuna Church,

Sweden, a musician can be seen holding a pipe in one hand and two bones

in the other in exactly the same way as musicians playing Irish

folk-music still do today. With regard to living musical traditions it

is in this connection interesting to turn one's attention to Gascogne

and Beam in France as well as to Aragon in Spain, where the tabor is

replaced by a drum with strings. This instrument is an ordinary

box-zither, i.e. a resonating box with strings tuned in fifths

corresponding to the tonality of the pipe played with one hand, and it

is beaten by the same musician with a stick in accompanying rhythmical

patterns in the same way as with a drum. Such an instrument was also

known in the Middle Ages under names including Chorus and is

seen illustrated in several places in connection with singing. As far as

I know there are no mediaeval pictures of the pipe and string drum, but

on the basis of well-known traditions and pictures of the pipe and

triangle and pipe and bones it seems highly unlikely that no attempts

were made to exploit this combination in the Middle Ages, if only to a

limited extent, since there is no iconographic or literary evidence to

support this claim.

Yet another mediaeval instrumental

combination with the pipe played with one hand can be mentioned here,

namely the double pipe (double flageolet), which means two pipes

played by the same person. This instrument was also of common occurrence

in certain regions. Howard Mayer Brown has for example established that

it was frequently to be found in 14th century Italy. It can often be

difficult to see which flutes, or perhaps reed instruments, are in

question. In some pictures it would seem that there are merely two small

recorders with the small range made possible by the few holes, but in

other cases there are clearly two pipes of the kind which are played by

one hand. The double flageolets are also most often illustrated

at a time and in such a way that makes it difficult to determine their

scale in relation to each other because of the lack of perspective in

the pictures, but from those which are clearest it would seem that in

most cases the flutes were the same size and with the mouths in the same

place, which would give the same tuning, and only exceptionally did the

pipes' proportions differ. Exactly which function these double flageolets

had is in many ways far more puzzling than that of the pipe and tabor,

whose built-in logic of melody and rhythm in combination with living,

accessible musical traditions to a great extent points forwards (or

backwards). But however clear or obscure an early practice may appear

today, historical fact will always support any argument that creative

experimentation, curiosity and the wish or demand that innovation at

whatever time in western history has been the driving force, also in

everyday music-making.

This of course also applies today, when one looks back in a forward-moving perspective.

Poul Høxbro, Copenhagen 1999

English translation: Gwyn Hodgson

Compilations: