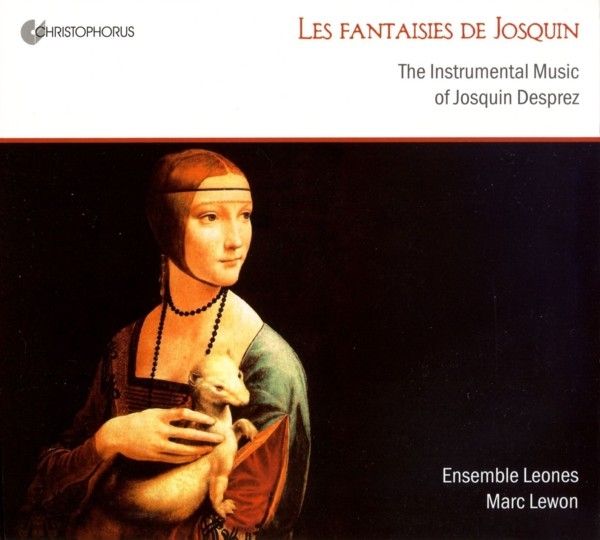

Les fantaisies de Josquin / Ensemble Leones

The Instrumental Music of Josquin Desprez

medieval.org

christophorus-records

leones.de

Christophorus 77348

2011

1. Ile fantazies de Joskin [3:07]

JOSQUIN Desprez (c. 1450-1521) / Intavolierung: Marc Lewon

2. La plus de plus à 3 [1:53]

JOSQUIN

3. [ohne Titel] à 3 [2:15]

JOSQUIN

4. De tous biens plaine [1:31]

Monodie, anonyme

5. De tous biens à 3 [2:09]

JOSQUIN

6. De tous biens à 3 [1:12]

anonyme

7. De tous biens plaine à 4 [1:13]

JOSQUIN

8. De tous biens à 4 [1:19]

de PLANQUARD, 15.Jh.

9. Ach hülff mich leid a 4 [7:58]

JOSQUIN / Adam von FULDA, Text und Bassusmelodie

10. La spagna à 3 [2:42]

anonyme

11. La spagna à 5 [2:47]

JOSQUIN

12. [ohne Titel] à 4 [3:05]

JOSQUIN

13. Fortuna desperata [1:45]

Francesco SPINACINO (2. Hälfte 16.Jh.-nach 1507) / JOSQUIN

14. Fortuna desperata à 3 [1:09]

JOSQUIN

15. Fortuna desperata à 4 [1:15]

anonyme

16. Une musque de Biscaye à 4 [2:04]

JOSQUIN

17. Une mousse de Bisquaye [2:16]

anonyme

18. Je sey bien dire à 4 [1:22]

JOSQUIN

19. La bernardina [1:27]

Francesco SPINACINO / JOSQUIN

20. A l'eure que je vous p.x. à 4 [1:07]

JOSQUIN

21. Helas madame à 3 [3:41]

JOSQUIN

22. Si je perdoys mon amy [2:32]

Monodie, anonyme / Begleitung: Baptiste Romain

23. Si j'ay perdu mon amy à 3 [2:18]

JOSQUIN

24. Si j'ay perdu mon amy à 4 [0:57]

JOSQUIN

25. L'homme armé [0:37]

Monodie, anonyme

26. L'homme armé à 4 [3:05]

JOSQUIN / Improvisierte Diminutionen: Leones

27. Cela sans plus à 4 [1:25]

JOSQUIN

28. A Dieu, mes amours [0:45]

Monodie, anonyme / Begleitung: Marc Lewon

29. Adieu, mes amours à 4 [2:02]

JOSQUIN / Bonifacius AMERBACH, 1495-1562

30. Adieu, mes amours à 4 [4:24]

JOSQUIN

31. Sei gelobt, du Baum [2:55]

Arvo PÄRT, *1935

32. Ile fantazies de Joskin à 3 [2:48]

JOSQUIN

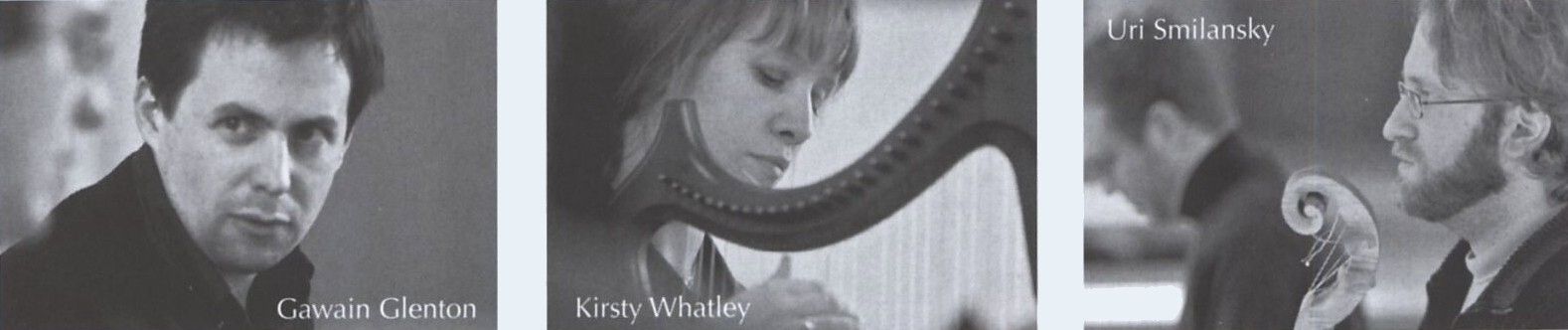

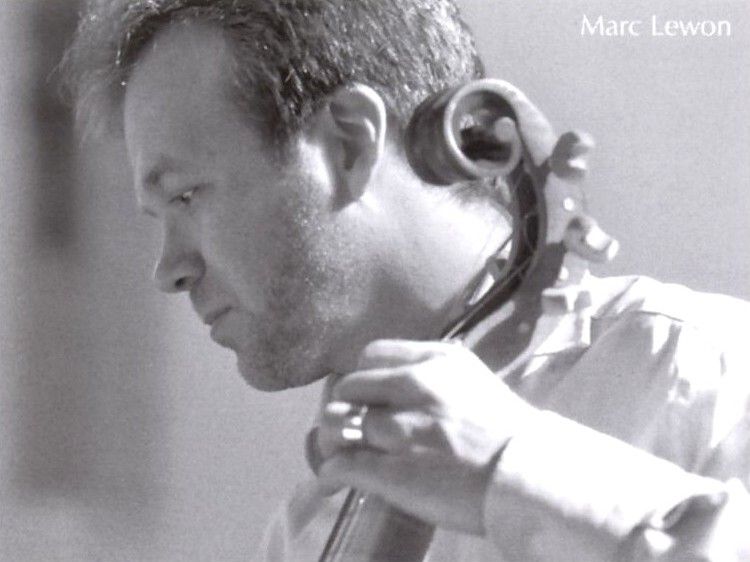

Ensemble Leones

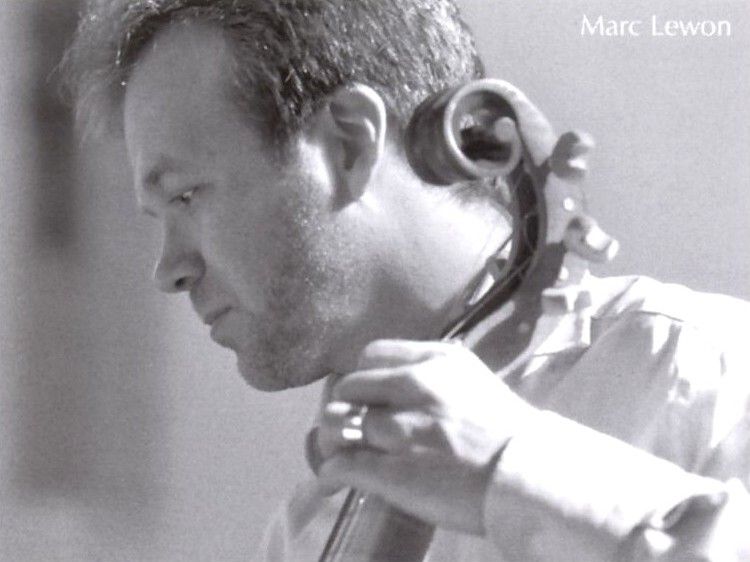

Marc Lewon

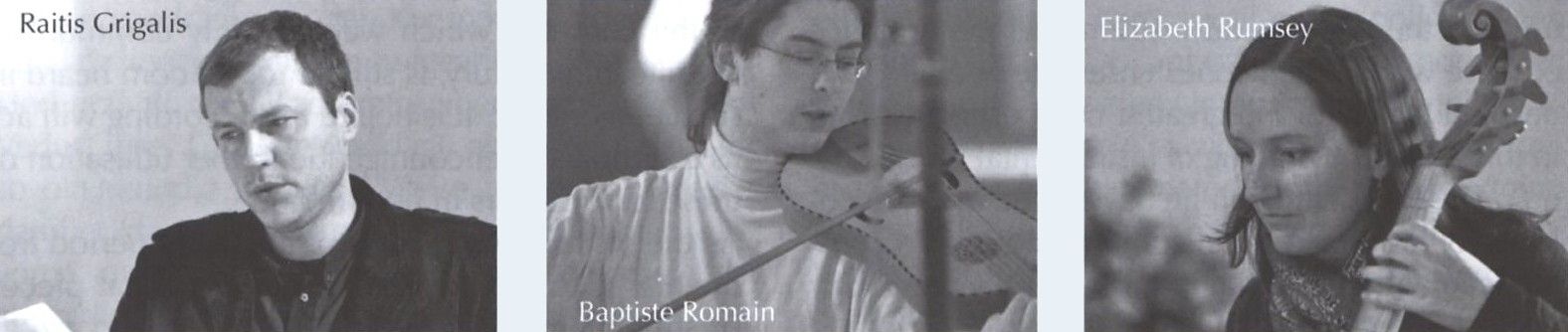

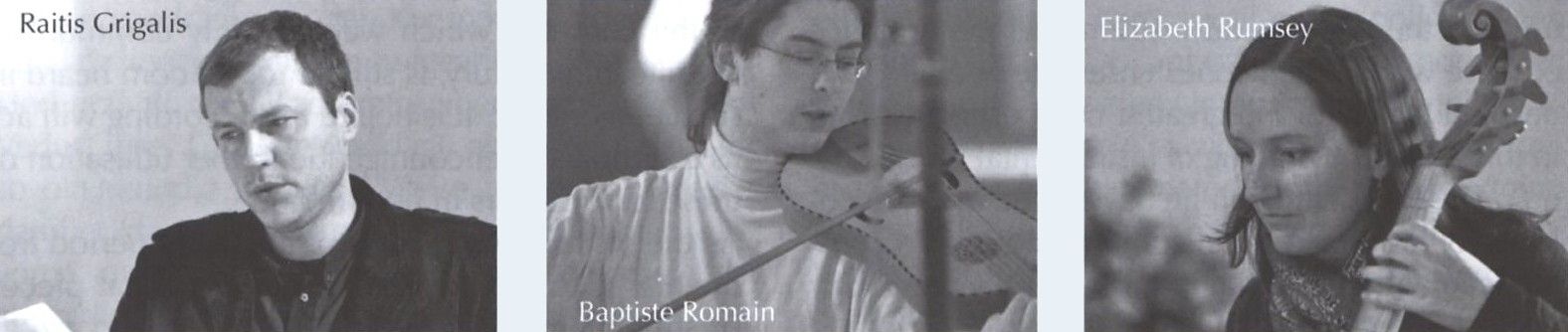

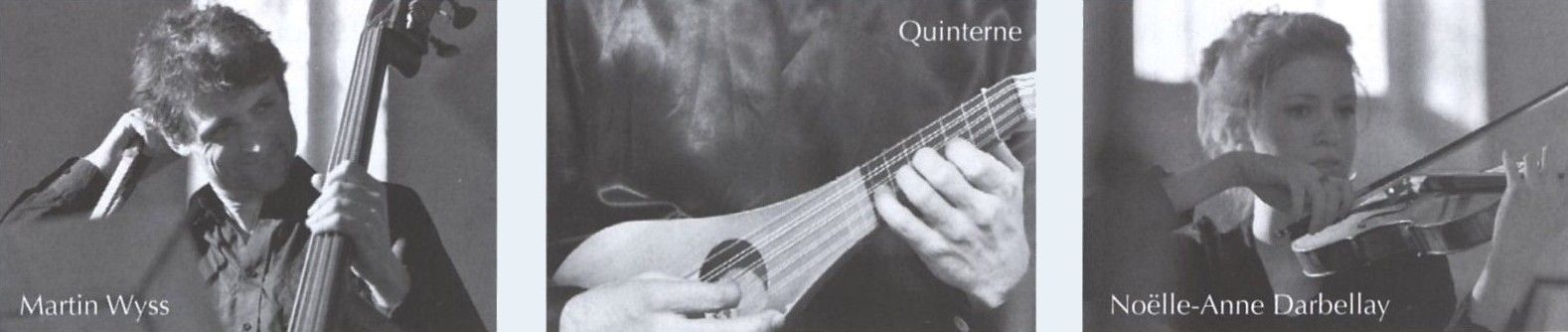

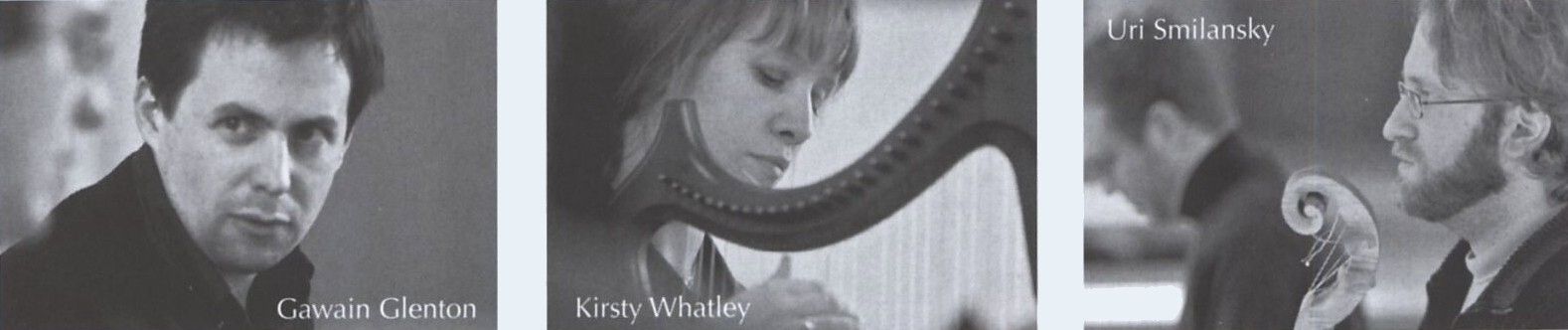

Raitis Grigalis, Bariton

Baptiste Romain, Renaissancevioline, Vielle

Elizabeth Rumsey, Viola d'arco, Renaissancegambe

Uri Smilansky, Viola d'arco

Kirsty Whatley, Harfe

Gawain Glenton, Zink

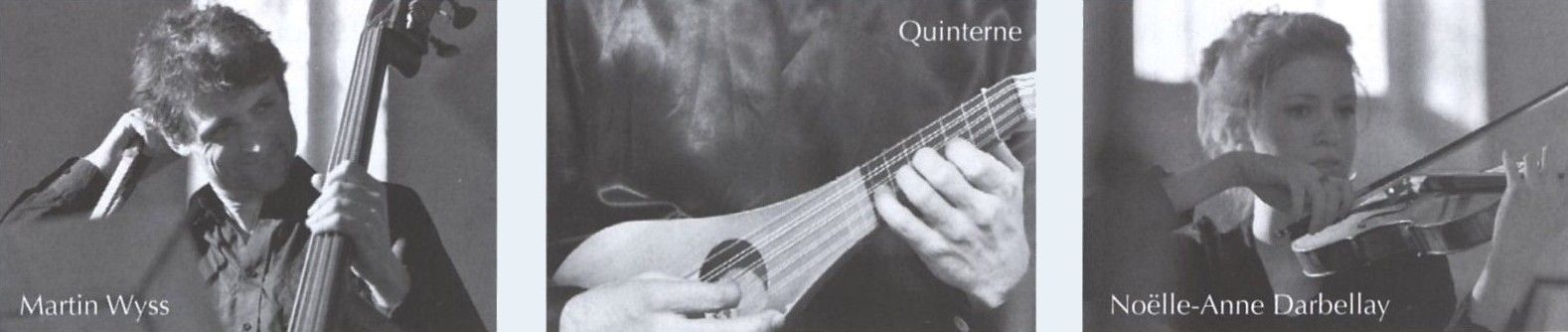

Marc Lewon, Plektrumlaute, Renaissancelaute, Quinterne, Viola d'arco

Gäste:

Noëlle-Anne Darbellay — Violine

Martin Wyss — Kontrabass

Recording: 22.-25.2.2010, Heilig Kreuz Kirche Binningen

(CH)

Recording producer & digital editing: Charles

Suter

Recording technician: Urs Dürr

Coproduction with DRS 2

De Flandria

von Marc Lewon

Aus dem späten 15. Jahrhundert ist mit einem Male eine ganze Flut

von Instrumentalstücken überliefert. Was bis dato keine

Spuren hinterlassen hatte, weil es die Spieler selbst und Schriftlos

ausgeführt hatten, erklärten die führenden,

„burgundischen" Komponisten nun zur Chefsache: neben der

Vokalmusik entwickelte sich die Instrumentalkomposition in Flandern zum

seriösen Betätigungsfeld. Dadurch wurde das Repertoire

eigener Bearbeitungen und Improvisationen der Instrumentalisten um neue

Gattungen erweitert, die sich hauptsächlich aus der Vokalmusik

rekrutierten: Zur stilistischen oder duobesetzten Tanz- und

Diminuitionsmusik gesellten sich Chansonbearbeitungen und ganze

„instrumentale Motetten" für Ensembles. Deren Struktur

konnte nun nicht mehr von der Interpretation eines vorgegebenen Textes

ausgehen, so dass sich eine genuin musikalische Rhetorik entwickelte.

Zwar kann die Überlieferung „textloser Musik" nicht mit

„Instrumentalmusik" gleichgesetzt werden, zahlreiche Hinweise

aber deuten auf eine weitverbreitete instrumentale Verwendung der Werke

hin. Einem der bedeutendsten Komponisten dieser ersten instrumentalen

Blüte ist die Debüt-CD des Ensemble Leones gewidmet: Josquin

Desprez mag sich als Komponist geistlicher Vokalmusik seine

größten Meriten verdient haben, als bislang

vernachlässigter Komponist weltlicher Instrumentalmusik soll er

jedoch mit dieser Einspielung gebührende Würdigung erfahren.

Die neue Art der instrumentalen Ensemblemusik eignet sich besonders

für homogene Besetzungen, die eine optimale klangliche

Verschmelzung gewährleisten. Von daher besteht die Kernbesetzung

für die vorliegende Aufnahme einerseits aus dem drei- bis

vierstimmigen Streicherensemble mit Viola d'arco, Vielle,

Renaissancevioline und -gambe, andererseits aus einem Zupfduo mit Laute

oder Quinterne und Harfe.

Zwei spezielle Klangfarben, die bislang wenig Beachtung bei der

neuzeitlichen Interpretation von Musik der Frührenaissance

gespielt haben, erhalten in dieser Einspielung besondere Gewichtung:

Zum einen wird die Harfe vorwiegend mit Schnarrhaken eingesetzt —

d.h. mit kleinen Stiften, die so an die Saiten geführt werden,

dass sie beim Anreißen einen Schnarrton erzeugen. Im 15. und 16.

Jahrhundert wurden Harfen generell mit dieser Klangfarbe gespielt, die

den Vorteil hat, sich im Ensemble zu behaupten und sich obendrein mit

Streichern und der plektrumgeschlagenen Laute hervorragend zu mischen.

Zum anderen ist der Zink, der mit Sicherheit seit spätestens dem

15. Jahrhundert eingesetzt wurde, viel zu selten mit seinem

wunderschönen Klang in der frühen Musik zu hören. Die

vorliegende Aufnahme sei für beide Klangfarben Anreiz und Argument.

Da instrumentale Werke dieser Frühphase häufig wie

Gelegenheitsstücke oder kleine musikalische Einfälle wirken

und von daher in der Regel sehr kurz sind, bot es sich für die

Einspielung an, sie zu größeren Einheiten zusammenzufassen.

In 14 Blöcken sind die Stücke auf der CD so geordnet, dass

sie innerhalb der dadurch entstandenen „Suiten" in sich

geschlossene Bögen darstellen und in ihrer Reihung über die

Aufnahme hinweg eine Entwicklung erfahren. Dabei wurden Josquins

Bearbeitungen in einen Kontext gestellt, der sie musikalisch

erläutert: Bei vielen seiner Stücke war ein schlichtes,

einstimmiges (Volks-)Lied Vorlage für die mehrstimmige

Ausarbeitung durch den Komponisten. Diese Vorlage wird hier von einem

Sänger mit schlichter Begleitung den instrumentalen Bearbeitungen

vorangestellt, so dass im Verlaufe der Suiten gewissermaßen

jeweils ein „Thema mit Variationen" zu Gehör gebracht wird.

Neue

Musik für altes Holz

von Marc Lewon

Als 1962 ein Stück Weißtannenholz auf einem Schweizer

Weingut ausgegraben wird, ahnt noch niemand, dass der kleine Baumstamm

seit dem Jahre 317 vor Christus dort verschüttet liegt. 2001 wird

das über 2000 Jahre alte Holz analysiert und sein hohes Alter

stellt sich heraus. Es wird entschieden, aus dem Fund Deckenholz

für zwei Instrumente zu gewinnen —eine Barockvioline und

eine Quinterne. Als über Vermittlung der estnischen Dichterin

Viivi Luik der Komponist Arvo Pärt davon erfährt,

verkündet dieser, ein Stück für die Instrumente aus

uraltem Holz schreiben zu wollen. Adrian Steger, der die Quinterne

für die Instrumentensammlung Willisau bei Richard Earle (Basel) in

Auftrag gegeben hatte, zog mich hinzu, den Bau des Instruments beratend

zu begleiten, das fertige Instrument zu besaiten und einzuspielen. Auch

hatte ich die Ehre, Arvo Pärt die Verwendung und Funktionsweise

der Quinterne zu erläutern. Und somit schließt sich mit

dieser Ersteinspielung der Komposition Sei gelobt, du Baum ein sehr

persönlicher Kreis, der die alten Instrumente und Klänge des

Ensembles eng mit der Gegenwart verknüpft. Ich danke Arvo

Pärt für das Vertrauen, die Ersteinspielung vorgenommen haben

zu dürfen.

Les

fantaisies de Josquin

by David Fallows

Ile fantazies de Joskin is one of the oddest known titles

for a piece of music in the fifteenth century. The word 'fantasia' had

already appeared in humanist writings about music and was to become

very common in the middle years of the sixteenth century for abstract

instrumental pieces. But this one looks like a polyphonic song —

a strange one, to be sure, with its unusual textures and wayward lines,

but in every other way keeping to the formal design one would expect

for a perfectly normal rondeau setting. Unfortunately the only source

for Ile fantazies — a marvellously elegant manuscript prepared

for Isabella d'Este at the court of Ferrara — has no full texts

for its music: just the opening words or the title of each piece,

entered in an extremely elegant and expensive script called littera

antigua alla romana with golden initials on every page but written

with a lofty disdain for the details of the texts (or the names of the

composers: he spells the simple word Josquin in six different ways).

From what we know of French prosody at the time, it is almost

impossible that the missing text for this particular piece opened 'Ile

fantazies'; so we must content ourselves with the mysterious title and

simply allow the music to beguile us. That the piece begins and ends

our CD is a hint at just one of the many mysteries that surround

Josquin Desprez and his music.

Over the past ten years those mysteries have changed. Formerly Josquin

was believed to have

been born around 1440; now it is agreed that he was at least ten years

younger, closer to the age of Isaac and Obrecht. It seems, too, that he

was a choirboy in Cambrai rather than, as earlier thought, St-Quentin,

which places him firmly in the circle of the great composers of the

previous generation, particularly Binchois, Du Fay and Ockeghem. As a

result, his early career has also changed: the old view was that he was

in Milan from the age of about twenty until he was almost forty; now it

looks as though he joined the Provençal court of 'good' King

René of Anjou in his early twenties, moving to that of King

Louis XI of France five years later, and that by his mid-thirties he

had served yet a third king, Matthias Corvinus of Hungary. It remains

true that very soon after 1500 he was fully accepted as the leading

composer of his day, as witnessed by the set of three collections of

his masses published in Venice by Ottaviano Petrucci, the first of them

going through six editions before Josquin died in 1521: no other

composer of those years was honoured by more than one volume devoted to

his music until Carpentras (who paid for them himself), and no other

book of music achieved so many reprints until Arcadelt's first book of

four-voice madrigals almost forty years later. But for the present CD

the important change is that his early career was in French royal

courts, not in Italy.

So even though Ile fantazies de Josquin probably originated as

a texted song in the later 1470s, when Josquin was with René of

Anjou, its appearance in Isabella d'Este's manuscript was certainly

intended for use as a purely instrumental piece. One of the main

innovations in music of the last quarter of the fifteenth century is

the rise in Italy of purely instrumental ensembles to perform music

that could have been written for voices. The same is the case with La

plus des plus, first found in the earliest printed collection

of music, Petrucci's Odhecaton (Venice, 1501), but almost

certainly also written during Josquin's time with René: here we

do actually have a possible text from a poetry manuscript of the time,

but again the music's appearance in its five surviving sources is

always plainly intended as an instrumental piece. For the next piece on

the CD we have no text at all, but its form clearly states that it is a

vocal piece of the years around 1500 based on a popular melody (yet to

be identified).

Another development in the last quarter of the fifteenth century

consisted of taking one or two lines from an existing masterpiece and

adding further lines. The most often used work for this was the rondeau

De tous biens plaine, by the Burgundian court composer

Hayne van Ghizeghem: at the latest count there were 54 arrangements of

that song. The two versions credited to Josquin both use canonic

techniques: that in three voices has the two lower voices in canon at

the fifth; that in four voices has two bass lines in unison canon at

the bizarre time-interval of only a minima.

This group of pieces on the CD ends with another setting of De tous

biens plaine that does exactly the same, with a close unison canon

in the bass; but it is credited to the otherwise unknown 'De

Planquard'. That obviously raises intriguing questions: how many

listeners can tell the difference in quality between the most famous

composer of the Renaissance and an entirely unknown figure? does the

difference matter? and could it be that De Planquard is just another

name for Josquin?

With Ach hillff mich leid we face a similar set of

questions. The piece takes its melody from a famous song by Adam von

Fulda (d. 1505), puts it in the bass register and constructs a new set

of counterpoints above it, beginning in three voices and then moving

into four voices for the Abgesang. The sources credit it to

four different composers: Pierre de la Rue (d.1518), Noel Bauldeweyn

(d. after 1513), Hans Buchner (1483-1538) and Josquin. From the first

moment, the music sounds German rather than Franco-Flemish, but that

would rule out La Rue and Bauldeweyn as possible composers as well as

Josquin. Moreover, all those ascriptions were done by copyists about

whom we know a fair amount, and all of them were intelligent enough to

recognize that this piece is in the Germanic style. All of them almost

certainly also knew enough to see that it fits very oddly indeed with

the other known works of Josquin and La Rue. The Josquin ascription is

in the keyboard manuscript of Fridolin Sicher, who first of all

credited the piece to 'Maister hansen' (Buchner) and then crossed that

out to add 'Josquin composuit'. Five considerations combine to suggest

that Sicher was right. First, he had studied with Buchner and therefore

had access to the best information about him. Second, there is in fact

a setting by Buchner of Ach hülff mich leid, reliably

credited to him in two other keyboard manuscripts of the time: Sicher

(or the writer of his exemplar) could easily have confused the two for

a moment. Third, Sicher — from whom we have two excellent music

manuscripts — was not inclined to be profligate with ascriptions:

unlike many other copyists of the time, he was perfectly happy to leave

pieces anonymous, though in this case he chose otherwise. Fourth, the

actual decision to cross out one ascription and substitute another is

extremely rare in manuscripts of the time and suggests positive

knowledge. Fifth, Sicher certainly knew that an ascription of the piece

to Josquin was counterintuitive, but he went ahead. Many listeners

today may think they know better; but by ignoring this piece we risk

losing a dimension of Josquin's output.

And that is another way in which the mystery of Josquin has changed in

recent years. It has always been clear that many spurious works were

circulating under Josquin's name: the difficulty was how to identify

them. Previously critics relied on a deep-seated musical judgment.

Today, most agree that this judgment (often based on a knowledge of now

discredited works such as Absalom fili mi and Missa Da pacem)

is easily misled. A harder look at the nature of the documentation

seems important. It may be worth adding that, of all the thirteen later

settings of Adam von Fulda's Ach hülff mich leid, only

this one survives today in more than two sources: it has no fewer than

nine sources. That obviously cannot stand as evidence that the

arrangement is by the prince of musicians (as Egidius Tschudi dubbed

him); but it at least shows that many musicians of the early sixteenth

century thought the piece worthy of serious attention — and

perhaps we should consider thinking likewise.

La spagna is a dance-tune with a history that goes back

to at least the middle of the fifteenth century and survives in many

different arrangements (Otto Gombosi listed 361 of them). Some of them

look a little as though they could have been improvised, but many

others are plainly worked with the most careful technical control. The

three-voice setting in Petrucci's Canti C (1504), also found in

two lute intabulations, is one of the most impressive of these: like so

much of the best music of its time, it survives anonymously.

As concerns the five-voice La spagna, though, we have more or

less the opposite situation. It survives in no fewer than seven

sources, all but two of which credit it to Josquin. But no recent

writer has accepted his authorship, for four main reasons. First, the

earliest known source for the work is a German print dated 1537, long

after his death, and the mid-century German prints are the main

locations of Josquin spuria, apparently added to bolster sales. Second,

the other ascribed sources are stemnnatically descended from that print

and therefore have no independent value. Third, the thick textures of

the setting are quite unlike what we otherwise know of Josquin's music.

Fourth, the setting is a stylistic twin of a setting of the melody T'Andemaken

op den Rijn credited to the famous music-copyist and political

agent Petrus Alamire, who therefore seems a more likely composer of the

La spagna setting. Even so, as in the case of Ach hülff

mich laid, there is a risk that we may lose a dimension of

Josquin's art by too quickly dismissing anything that is at first

glance unlike his more famous works.

The same is true of the lovely textless piece that survives only in a

manuscript in Zwickau dated 1531. At first blush it sounds as though it

is by the composer of Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen (whose

identity is also now in question), but that must have been obvious also

to any listener in 1531 and therefore to whoever wrote Josquin's name

on the music. Unlike the case of the five-voice La spagna, this

cannot have been for any financial benefit: the copyist was just adding

information that he thought would interest or enlighten his reader.

Perhaps we can take it in the same spirit.

Fortuna desperata was one of the most popular three-voice

songs of the 1460s, sometimes credited to Busnoys but more likely to be

by an obscure Florentine singer called Felice di Giovanni Martini. We

hear it first in a florid arrangement by Francesco Spinacino, then in a

version credited to Josquin (in the Segovia choirbook, which is hardly

a trustworthy source for Josquin) and finally in an anonymous version

from the Bologna manuscript Q18.

Une musque de Biscaye tells the story of a knight

attempting to seduce a shepherdess from Biscaye, whose language he

cannot understand. Here Josquin's music takes the popular tune (known

from several other settings, among them four mass cycles) and treats it

in canon at the fourth between the two upper voices; and for a short

while all four voices are in pure canon. In Je sey bien dire

he takes what must be another popular tune (though this one is not

otherwise known), puts it in the tenor in the middle of the texture and

builds around it a counterpoint of truly bewildering complexity and

rhythmical intricacy.

With La bernardina we encounter a piece a little like Ile

fantazies de Joskin and La plus de plus but with the

crucial difference that it can certainly never have carried text. That

is to say that its form shows none of the articulation points that

characterize any setting of poetry: this is pure musical fantasy.

So is the next piece, A l'heure que je vous p.x., as it

is labelled in its only source. What on earth the title could mean,

nobody has yet attempted to explain. But the music is clear enough,

built within two outer voices that are in pure canon at the unusual

interval of a ninth. Technically, this is not as hard as it may sound,

not least because Josquin runs those canonic voices essentially in

parallel tenths throughout, though the result has a dazzling range of

musical ideas.

But in terms of producing unexpected and strange music, there is

perhaps nothing to match Helas madame: it looks like a

song; and its lines work precisely like those of a song; but the

extended musical form is quite unlike that of any other secular song in

the fifteenth century. Once again, we have no text in any of the four

fifteenth-century sources that contain it; and it looks very much in

this case as though the strange form was driven by a poem; but it is

very hard indeed to imagine what form that poem could have had, and it

is impossible to find a poem among the literary sources of the time

that could match this music. Once again, then, Josquin presents us with

an insoluble mystery.

Si J'ay perdu mon amy is the kind of tune used many

times by francophone composers of the early sixteenth century. lt tells

the story of a lady who has lost her lover but laments the loss in such

apparently cheerful terms that she is plainly happy to be able to start

again with a new lover. Both the three-voice and the four-voice

settings ascribed to Josquin betray this unmistakable joviality

throughout.

But nobody can guess the mood of Josquin's little setting of the L'homme

armé melody. Two of his most magnificent achievements

are mass cycles on this melody, glittering works that show his

virtuosity and resource at every turn. Here, though, he seems almost to

be resisting show of any kind. Of the various commentators over the

years, Gustave Reese called it 'gay', Richard Taruskin called it 'fun',

Edward Lowinky called it 'singularly unattractive' whereas August

Wilhelm Ambros (1868) called it 'unerquicklich und trocken, zum

Glücke sehr kurz'. In this performance it is treated as a basis

for improvisation.

The next two pieces are among his earliest songs. Cela sans plus

probably began life with a full rondeau text that happens not to have

survived, though its immaculate counterpoints make it work magically as

an instrumental ensemble piece. Adieu mes amours was one

of Josquin's most successful works and the first of his works to

achieve true international fame: it began life as a combinative

chanson, with a full rondeau text in the discantus and a popular song

distributed between the two lowest voices; and then, like so many of

his works, it found its way into the international instrumental

repertory, being printed for the last time in Benedict de Drusina's

lutebook of 1556, some eighty years after it had been composed.