Ossi-Renaissance

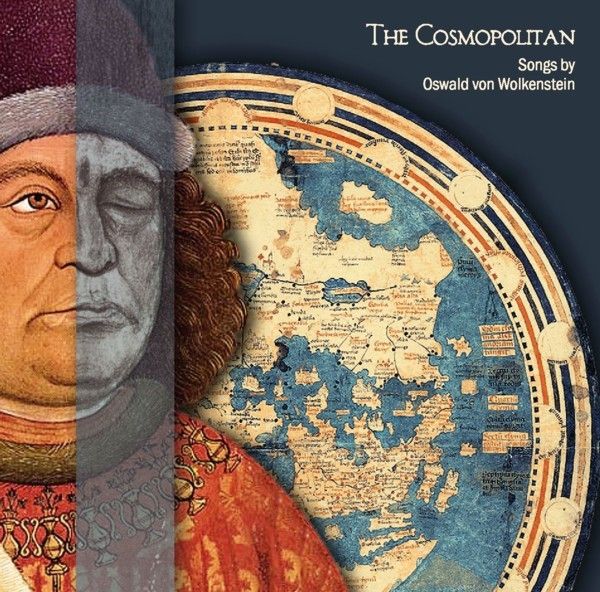

Oswald

von Wolkenstein was a man of rather coarse manners. He looked coarse.

His portrait is even coarse, no whitewashing: beard stubbles, scars, one

eye shut for a lifetime. He looked more like a robber baron than a

noble semblance of knighthood in the Romantic sense. This impression is

conveyed and intensified by many of his song texts. Performers have

taken their cue from these: this roughneck, this bardic master-poet of

drastic phrasings must also have been musically rough, a kind of tavern

minstrel in a castle atmosphere: “strum, strum”. Very gradually, over

the course of many years, a change of perspective has crept in. The

results can be heard on this CD. The man from the lower (South Tyrolean)

nobility, the singer, instrumentalist, tunesmith (as one might formerly

have said): as a mercenary he was not just along for the ride in

campaigns between Northern Europe and Northern Africa – he was receptive

to everything new, especially music. Mostly in southern lands, at

numerous courts, listening to the performances of colleagues, he picked

up on new and cutting-edge developments, and this was above all:

polyphony.

He adopted musical models for his new texts. He

apparently composed some too, showing himself to be rather a man of the

Renaissance than of the late Middle Ages. This comes across when

listening to these new recordings, decidedly different from those

largely familiar by now. Even monophonic songs: artful.

One song on this CD exemplifies this with particular clarity: Durch aubenteuer tal und perg

(Kl 26, Track 4). Sung here by Marc, who accompanies himself on the

lute, is one of Oswald’s most radical texts: a personal account of

escape, capture, imprisonment. (The translation can be found starting on

page 523 of the revised re-issue of my Wolkenstein biography)[1]. In

this song text the poet truly did not mince words. But what we hear is a

different matter. The coarse material is filtered as it were by musical

means, it becomes refined. The radical becomes musically elevated and

idealised. The melismas for example, are carefully calculated by Oswald:

no longer a mere addition to monophony, mostly shrugged off until now,

they are an essential ingredient of his style. That which is coarse and

drastically phrased is subtly articulated in music. A metamorphosis

takes place: a merging of intentions of both poet and composer, whose

setting adapts and transforms the latest trends. In this way the

seemingly plain and simple song blends into the soundscape of delicate,

subtle polyphony. We have to see Wolkenstein differently, when listen to

him here.

Dieter Kühn

The Songs of Oswald von Wolkenstein

While

the lives of most late medieval poet-composers are hidden to modern

scholars, that of Oswald von Wolkenstein stands out in illuminated

contrast: his life and acts are chronicled in over one thousand

non-literary accounts [2]. These sources, however, surprisingly fail to

describe Oswald “the Minnesänger”, but rather provide numerous

details about Oswald the politician, diplomat, landowner, and aggressive

legal opponent. Practically all we know of his poetic and musical

activities has been transmitted through two large manuscripts, now in

Innsbruck and Vienna, which he commissioned personally in order to

preserve his works. These manuscripts constitute virtually his entire

œuvre, around 130 songs altogether. As one might expect, their contents

overlap for the most part, though some contributions are unique to only

one manuscript. Duplicates appearing in both sources, on closer

inspection, are in fact not identical in detail: through these, Oswald

allows us to peer into his methods by transmitting texts that straddle

the border between authoritative and performance versions. Despite

numerous recordings making many of his songs accessible to a wide

audience, there remains compositions that have yet to reach modern ears —

either problems with their notation have yet to be satisfactorily

solved, or the songs are simply too strange and alien to be considered

accessible.

Oswald’s œuvre presents a broader artistic spectrum

than we can observe in any other author of the German middle ages:

foremost, it is both poetically and musically sophisticated, ranging in

tone from simple to complex; it displays not only both traditional and

experimental approaches, but also those that reflect new developments of

his time. The songs are demanding to perform: the singer must act as

storyteller, all the while negotiating the phenomenal melodic ranges

encompassed in his monophonic songs, while his polyphonic works require

virtuosic effects to subtly enrich the sound world to which they belong

[3].

This recording is dedicated to a selection of Oswald’s songs

which have been, for the most part, rarely heard today. Among these are

polyphonic pieces for which we have made a first functional edition.

These include Freu dich, du weltlich creatúr (Track 3), Gar wunniklich hat si mein herz besessen (Track 5) and, as the personal wish of Ulrich Müller, Wol auff, wol an

(Track 9), a song which he had hoped one day to hear for himself.

Ensemble Leones runs the gamut of performance possibilities, employing

the bandwidth of the medieval instrumentarium: from a capella voices to

the full sound of the ensemble; from Horn des Wächters, which

blurs the border between “signal” and “musical” instrument, across the

humanistic revival of the cetra to the traditional instruments of the

German-speaking world: vielle, lute, harp, hurdy-gurdy, bagpipes and

transverse flute.

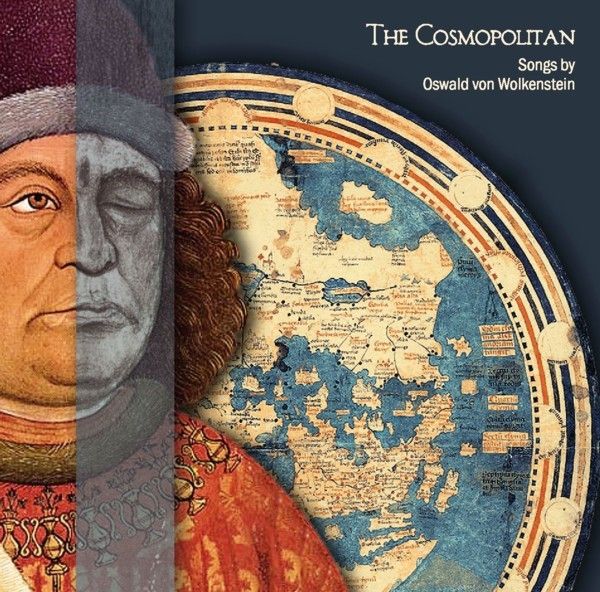

The Cosmopolitan – A little Programme Guide

The

compact size of this booklet format does not allow the inclusion of

texts and translations, so instead we offer the following guided tour of

all the tracks, with details about the contents and characteristics of

each piece.

Texts and translations into modern German, English

and French are available for download as a PDF file from the ensemble’s

homepage (www. leones.de). Song texts in their original versions are

also freely accessible from the website of the “Oswald von

Wolkenstein-Gesellschaft”: www.wolkenstein-gesellschaft.com/texte_oswald.php. An English translation of all Oswald lyrics was published by Albrecht Classen [4].

Oswald employed seven languages to create [1] Do fraig amors,

his macaronic masterpiece of a love song, dedicated to his beloved

wife, Margarete. The refrain highlights the didactic fun of this Babelic

banter: “Do it in German and in Italian, rouse it in French, laugh in

Hungarian, bake bread in Slovenian, let it resound in Flemish! The

seventh language is Latin”.

The postlude to this first song is [2] Stampanie,

an instrumental arrangement upon “Do fraig amors” in a dance format to

which Oswald often refers. When he uses the word “Stampanie” (=

estampie), however, he usually intends it as a metaphor for socializing

with convivial company.

To create [3] Freu dich, du weltlich creatúr,

Oswald may have recycled the music of a French chanson that has not

survived in any other sources. We should be thankful for Oswald’s

enthusiasm as a collector – without it, this composition (and others!)

would have been lost forever. We present it here in an instrumental

arrangement for the solo plectrum lute.

[4] Durch aubenteuer tal und perg

fulfils all our expectations of what an Oswald song should be like: a

monophonic epic of an autobiographic adventure tale; fifteen strophes of

brilliant and self-styling entertainment. The story goes as follows:

after having fallen into legal troubles, Oswald was captured and held in

the dungeons of a number of castles before he was finally led before

his sovereign, Frederick, Duke of Austria. He cleverly weaves into his

story a description of the journeys that brought him well around half

the known world: from Heidelberg on to England, Scotland, Ireland, over

the seas to Portugal, and even to Marocco and Granada. Rather than

sharing his table with the high nobility, as he was used to on those

journeys, he had to share his plank bed with a servant – quite a fall

from grace! He was heavily guarded in those dungeons; he has traded in

his knightly spurs for hard iron cuffs. Despite his situation he

obviously has not lost his sense of humour: “For twenty days I was lying

there, instead of dancing. What I lost in cloth at my knees I saved in

the soles of my shoes.” Finally, Duke Frederick decided that he would

rather enjoy Oswald’s company than have him moan away in his prison: “We

should be singing fa, sol, la together and writing courtly poems about

the beautiful ladies” — or at least these are the words that Oswald put

in his sovereign’s mouth. In any case, he was released, for which he

thanks both his duke and God. In the end, he seems to have learned his

lesson: “The fire of my vanity has often been quenched by Him without

the need of water.”

[5] Gar wunniklich hat si mein herz besessen

is a heartfelt love song in the form of a two-voice canon. The music

appears to be of French origin, though no concordance has been found.

Oswald cleverly alternates melismatic passages with syllabic text

setting in an interweaving of accompaniment and recitation. Despite the

intimate and complex exchanges between singers, the text can always be

understood.

The impressively large-scale [6] Es seusst dort her von orient is a monophonic Tagelied.

Oswald opens the song from the perspective of the far-travelled wind

who, having swept through all the lands from India, across Syria, Greece

and Northern Africa, to Spain and Southern France, finally reaches a

pair of lovers in South Tyrol who have spent the night in secret. The

watchman’s horn announces the dawning day – a signal also that it is

time for the lovers to part ways. Their farewell words and vows turn to

amorous embraces, and one thing leads to another... the refrains develop

into explicitly erotic descriptions. Oswald at his best!

The two-voice [7] Ach senliches leiden, today one of Oswald’s most popular songs, is densely packed with Schlagreimen

— literally “rhyming blows” — that vividly describe the pangs of love

(e.g. “crying, sighing, dying!”). Oswald’s unusual metaphors in this

song reveal his experience of a sea voyage to the Holy Land. He compares

himself to the dolphin who dives into the deep of the sea when a storm

comes and resurfaces only when the sun returns to bathe him with light.

The outcome of this lover’s lament remains unresolved: “Waiting gnaws at

me, hoping tortures me; it robs me of my senses!”

[8] Wes mich mein búl ie hat erfreut

is a typically catchy Oswald tune, whose charm, paired with his ironic

autobiographical text, has made it one of his most popular. Our

arrangement for the bagpipes highlights the melodic qualities of this

piece.

With [9] Wol auff, wol an we join “Ösli” and

“Gredli” (Oswald and his wife Margarete) in the bathtub. Two voices

represent our protagonists in this joyous springtime song. One of the

most peculiar polyphonic settings in Oswald’s œuvre, its notation

presents numerous editorial puzzles. How should we understand its

rhythm? Its counterpoint? With this premiere recording, Ensemble Leones

offers an example of how Oswald’s “organum-like” pieces may have worked

in practice. Certainly the cascading parallel fifths – typical of this

style – have a fantastic effect when the two lovers descend into

innuendo, singing: “Put on leaves, little shrub, sprout, little herb!

Off to the bath, Ossi, Gretli! The blossoming of the flowers overcomes

our tiredness”.

[10] Ain gút geboren edel man is

one of the few three-voice settings in Oswald’s manuscripts. As with

other polyphonic settings, it is probably a contrafactum for which no

concordance has been found. We have arranged this delightfully

unpretentious composition for transverse flute and cetra.

It is not entirely clear if the Tagelied-canon [11] Nu rue mit sorgen was meant to be sung by two or three voices. As it works very well with three, we decided that the two lovers in their morning

embrace

should be joined by the watchman on the tower, represented by a third

singer. Despite the disappearance of the morning star making them aware

they must part (lest their secret meeting be discovered!) they move

closer together. Finally they do separate and bid each other a fond

farewell.

“Who is she who is more radiant than the sun, who

boldly quenches and revives the withered wreath? Who is she who leads

the circle dance, and grants the mild month of May the sprouting of new

plants?” These rhetorical questions and those that follow in [12] Wer ist, die da durchleuchtet

have only one answer, which Oswald gives indirectly. She has the power

to lead the believers away from the path to hell: “Oh pure, honest lady,

our shield; break the devil’s spear, deflect his lance, beauteous

virgin! Amen”.

[13] Ich klag is another polyphonic

setting that survives thanks to Oswald’s avid borrowing. He apparently

meant to write a text to this three-voice composition, but never quite

got around to it. It remains a fragment, a sketch. We perform the music

instrumentally: first as a plectrum lute solo, then with vielles and

transverse flute.

[14] Mit gúnstlichem herzen is a canon for New Year and, with its extremely close entries, seems almost like a counterpart to Gar wunniklich hat si mein herz besessen (Track 4).

One

voice begins a phrase, the second then takes over and completes both

meaning and rhyme, and soon both voices mutually interject to create a

dazzling effect. The musical setting joins two independent texts

together to yield new meanings. As the first proclaims: “Out of

heartfelt affection I wish you an especially good New Year and whatever

on earth your heart might desire!” the second voice answers

simultaneously, “Your singing and pleasantries please me, that is truly

so; my loyalty shall be your reward: this wish, my love, shall come true

for us both”. The following interwoven phrases produce a new

“con-text”: “It shall be like that, treasure, truly” – “I thank for the

words and am your servant”. - “Think of me, my companion!” - “If it

pleases you always anew, than it shall be so!” The second verse reveals

that the dialogue partners are in fact again none other than Oswald

(“Os”) and his wife Margarete (“Gret”).

The extremely virtuosic, two-voice [15] Herz, prich makes excessive use of an associative string of Schlagreime

(see track 7), almost like a stream of consciousness. The two voices

toss single words, or even single syllables, at each other, which

complement each other and combine to form an intelligible text. With

these short words, the pangs of love can almost be felt physically:

“Heart, break! Seek revenge! See — pain spoils happiness and turns

natural love into eternal sorrow”.

Oswald’s linguistic prowess,

which we witnessed in the beginning of this recording, shows itself

again with a setting that incorporates no fewer than five languages.

[16] Bog de primi was dustu da includes texts in German, French,

Latin, Slovenian and the Romance dialect from his valley: Ladin. We

frame this refined, macaronic love song with an instrumental version of

what is now probably Oswald’s most famous drinking song: Wol auff, wir wellen slauffen.

Marc Lewon

1. Kühn, Dieter: Ich Wolkenstein. Die Biographie (Erweiterte Neufassung), Frankfurt/Main (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag) 2011 (= Das Mittelalter-Quartett: Viertes Buch).

2. Complete life accounts are available in an edited version with commentary in Schwob, Anton (Ed.): Die Lebenszeugnisse Oswalds von Wolkenstein. Edition und Kommentar, 5 vol. Wien et al. (Böhlau Verlag) 1999-2013.

3.

An overview of the state of Oswald research with a comprehensive

bibliography is available in Müller, Ulrich and Margarete Springeth

(Ed.): Oswald von Wolkenstein. Leben – Werk – Rezeption, Berlin, New York (Walter de Gruyter) 2011.

4. Classen, Albrecht: The Poems of Oswald von Wolkenstein. An English Translation of the Complete Works (1376/77- 1445), New York (Palgrave Macmillan) 2008 (The New Middle Ages).