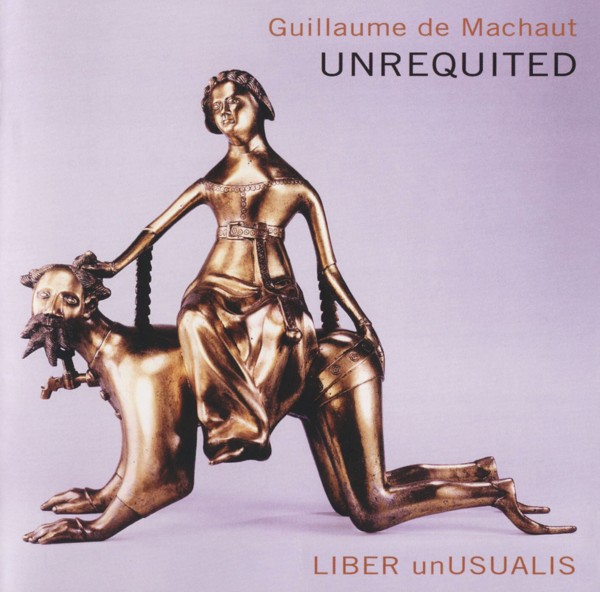

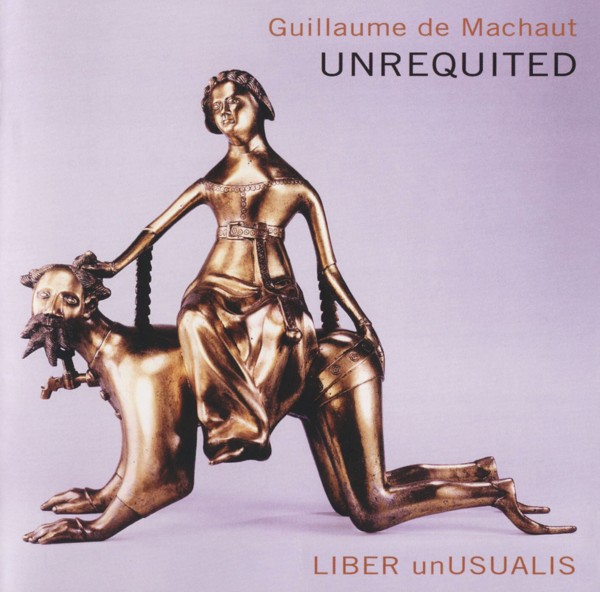

Guillaume de MACHAUT. Unrequited

Liber unUsualis

medieval.org

Liber unUsualis 1001

2003

Guillaume de MACHAUT

1. Felix virgo, mater Christi ~ Inviolata genitrix ~

Ad te suspiramus gementes et flentes [3:50]

motet · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB, tenors WH, JS

2. Trop plus est bele que biauté ~ Biauté parée de valour ~

Je ne sui mie certeins d'avoir amie [2:28]

motet · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB, tenor WH

3. J'aim miex languir en ma dure dolour [5:25]

ballade · tenors WH, JS

4. Dame, ne regardes pas [7:04]

ballade · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB

5. Quant en moy vint premierement ~ Amour et biauté parfaite ~

Amara valde [3:40]

motet · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB, tenor WH

6. Donnez, signeurs, donnez à toutes mains [5:22]

ballade · mezzo-soprano CB, tenors WH, JS

7. Martyrum gemma latria ~ Diligenter inquiramus ~

A Christo honoratus [3:26]

motet · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB, tenor WH

8. Je ne cuit pas qu'oncques à creature [5:44]

ballade · mezzo-soprano CB, tenor WH

9. Dame, de qui toute ma joie vient [6:23]

ballade · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB, tenors WH, JS

10. Qui es promesses de Fortune se fie ~ Ha! Fortune trop sui mis ling de port ~

Et non est qui adjuvet [1:45]

motet · mezzo-soprano CB, tenors WH, JS

Pierre des MOLINS

11. De ce que foul pense [5:43]

ballade · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB, tenor WH

Franciscus ANDRIEU

12. Armes, amours, dames, chevalerie ~ O flour des flours de toute melodie [7:24]

ballade · soprano MG, mezzo-soprano CB, tenors WH, JS

LIBER unUSUALIS

Melanie Germond, soprano

Carolann Buff, mezzo-soprano

William Hudson, tenor

with

Jordan Sramek, tenor

PROGRAM NOTES

by Carolann Buff

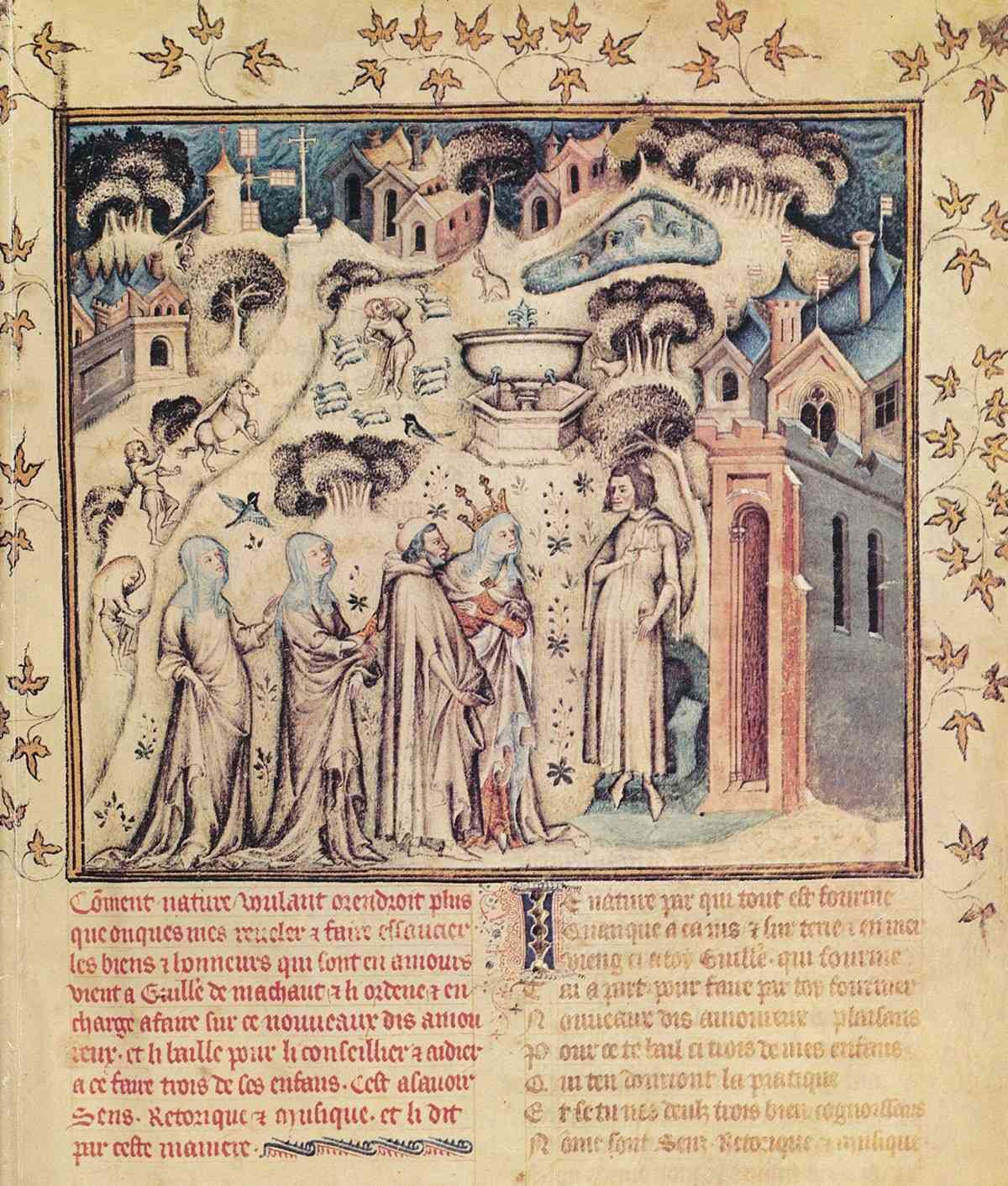

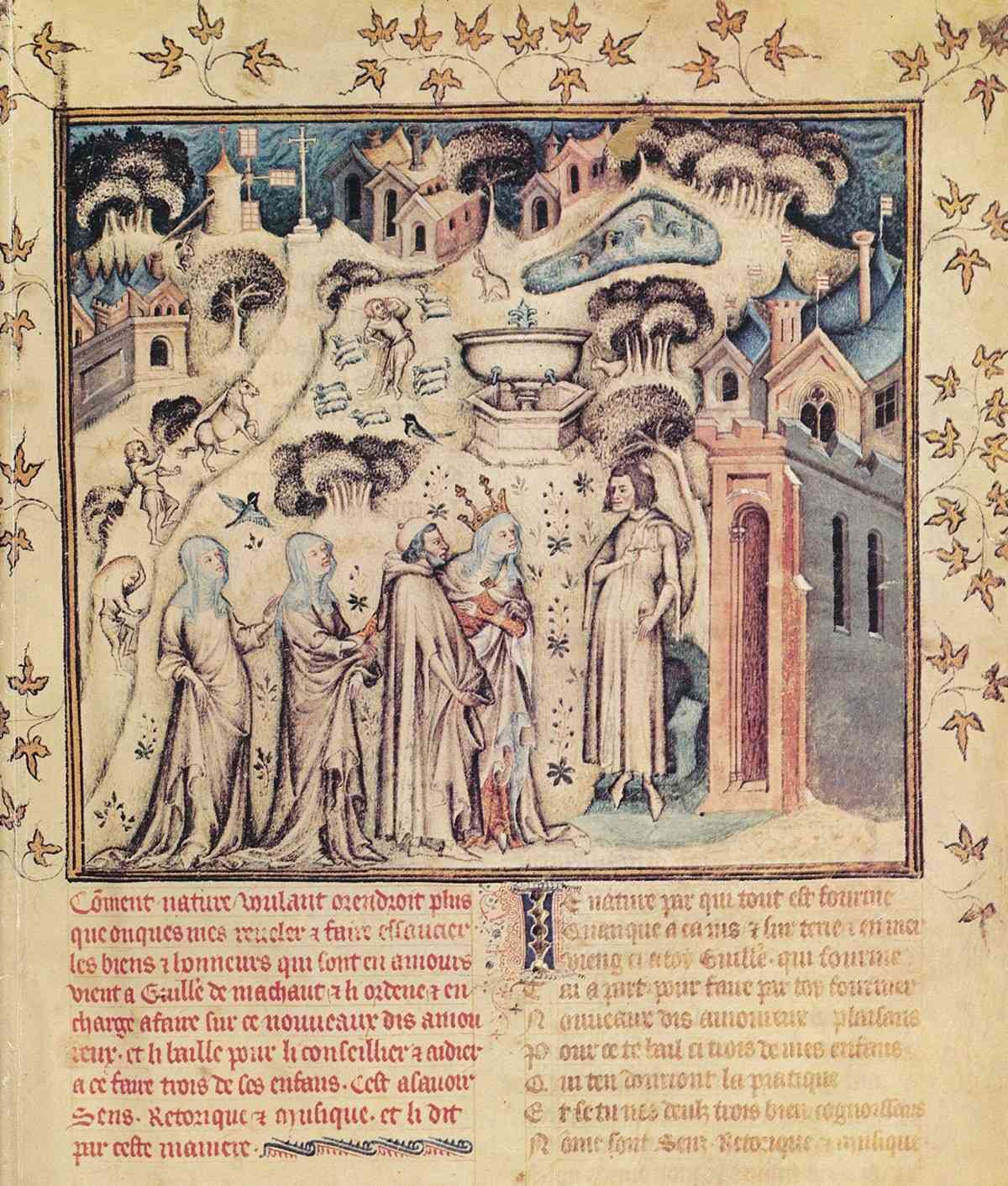

One of the more famous images

of Guillaume de Machaut (c.1300-1377) is of the composer encountering

Nature who presents to him her children—Science, Rhetoric, and Music.

Machaut certainly utilized these gifts in all that he undertook. In his

lifetime, he produced over 100 known musical works including a complete

mass and wrote numerous poems included in some 70 different manuscripts.

Known as a great composer and poet in fourteenth-century France, his

lasting influence still ripples outward to performers and scholars

today. Machaut's existing legacy is remarkable because of his careful

attention to the smallest details of his works, the sheer volume of his

musical and literary output, his attentive supervision and organization

of his manuscripts, the quality and presentation of his music, and the

large number of musical genres in which he was fluent. Even in his own

time, Machaut was considered one of the primary influences on music

composition in the fourteenth century.

Despite being born into a

family of simple means, Machaut managed to enter the circle of his

influential and wealthy patrons. Very early in his career he was

employed by Jean of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia, and later by Jean's

daughter, Bonne. Other notable personages who patronized Machaut were

Charles II King of Navarre, Jean Duke of Berry, Philip the Bold Duke of

Burgundy, and future kings Charles V and John II of France. In addition

to employment by nobles, Machaut held several well paying benefices as

canon, as at Reims Cathedral and at the Church of St. Quentin in

Vermandois, which kept him in considerable financial stability for much

of his life. This substantial wealth and his relative fame allowed him

the luxury of time and freedom to mold carefully all of his works,

literary and musical, into art.

Machaut is best known for being

the link between the "new art" of music innovated by Philippe de Vitry

(1291-1361) and the style of composition of the later middle ages.

Vitry's compositional system is based upon the enormous range of musical

expression made possible by new notational techniques explained in his

treatise, Ars nova (c. 1322). Machaut used these notational

devices and existing poetic forms to create a new and distinct sound in

his compositions, having a lasting influence on the next two generations

of composers.

The isorhythmic motet, a musical genre based on

borrowed plainchant melodies or fragments and organized into rhythmic

and melodic groups, had steadily gained prominence as a formula since

its conception in the twelfth century. Until the 1330's, this form was a

lyric genre, often in the vernacular with multiple texts, with literary

themes such as love and fortune. Two examples are the motets Quant en moy vint premierement / Amour et biauté parfaite / Amara valde and Qui es promesses de Fortune / Ha! Fortune trop sui mis ling de port / Et non est qui adjuvet.

In the 1340's, this practice changed. The multiple texts and the Latin

tenors remained, but the texts of the upper voices became more

political, with motets dedicated to particular persons or in honor of

certain events. The motet Felix virgo, mater Christi / Inviolata genitrix / Ad te suspiramus gementes et flentes is a prayer for peace to the Virgin Mary after the siege of Reims by the English during the Hundred Years' War. Martyrum gemma latria / Diligenter inquiramus / A Christo honoratus

is a motet in honor of St. Quentin, probably written for the Collegiate

Church of St. Quentin Vermandois. One motet that serves both lyrical

and honorary functions is Trop plus est bele que biauté / Biauté parée de valour / Je ne sui mie certeins d'avoir amie.

This motet is unusual because, although it is a late period motet, the

upper voices sing vernacular texts. The tenor is also not a piece of

Latin plainchant, but probably a French song tune. In addition, the

tenor is not truly isorhythmic, but organized like a rondeau. Scholars

conjecture that the style of text setting and the rhythmic organization

of this piece reflect Machaut's mature style, circa 1350, and that the

song may have been intended as a memorial benediction to Bonne of

Luxembourg. Machaut consistently places this motet last in his

manuscripts highlighting the final "Amen" in the text.

The

ballade genre, unlike the motet, is a relatively new song form in the

fourteenth century. Machaut borrowed the form from poetry and is

credited for being a major innovator in this genre. The duet ballades

such as J'aim miex languir en ma dure dolour; Dame, ne regardes pas; and Je ne cuit pas qu'oncques creature

reflect Machaut's careful attention to the original poetic forms,

matching the text to his musical settings. Poetry and music were

irrevocably linked in all of Machaut's writings. Not only did he

conceive of the music and text as one idea, but he also segued

comfortably from narrative to poem to song. Dame, de qui toute ma joie vient from the longer literary work, Remede de Fortune,

is a song sung by the protagonist, the poet, after seeing his beloved

in a garden and being comforted by the character of Hope. One ballade, Donnez, signeurs, donnez toutes mains,

is unusual because the text's theme is more similar to honorary motets

being composed in the late fourteenth century than the common topic of

unrequited love prevalent in other ballades. This ballade, on the

subjects of largesse and the honor of nobility, may have been intended

for Jean Duke of Berry who was sent as a hostage to the English in the

terms spelled out at the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. One ballade in this

collection is not by Machaut, although it was attributed to him in at

least one manuscript and is published in many manuscripts together with

Machaut's compositions. De ce que foul pense, by P. de Molins

(fl. mid-fourteenth century), was probably the most widely circulated

piece in fourteenth-century France and is even woven into a tapestry

called "Le Concert." Molins, like Machaut, was associated with Jean Duke

of Normandy (later King Jean II of France). His beautiful song setting

reflects how well the ballade form had influenced Machaut's

contemporaries.

Machaut's own voice is clearly heard in his music

not only because of carefully created and preserved manuscripts which

the composer himself oversaw, but also because he is certainly the

author of almost all the poems which he set to music. The texts from

Machaut's prolific output of poems present a clear image of the man, his

lusts, and his tribulations. Most notably, his words illuminate the

image of a great composer and artist. By combining poetry, song forms

and music, Machaut fully realizes the offerings Nature has given him:

the genre formulas are the presence of Science; Rhetoric is in his

poetry; and his wonderful melodies are the gifts of Music.

AIthough

there are many clues to performance in Machaut's manuscripts, so much

more abundant than any of his contemporaries, there are certain

challenges that remain for the modern performer. The issue of tuning,

especially for voices that so easily slide into just intonation, is

notable. Machaut clearly intended his music to have a certain element of

tension and release which is heightened by tuning in the Pythagorean

system. The wide major third of Pythagorean tuning leads the ear to

resolve outward to the pure fifth and the narrow minor third inward to

the unison. Another adjustment for the modern performer is the emphasis

on the linear as opposed to the vertical. What might appear as

syncopation in modern meter is really a shift by an eighth or quarter

note of a horizontal line. Performers succeed when they consider the

interaction between voices as happy coincidences of conjunction leading

to common goals. The texts, so obviously important to Machaut the poet,

must be pronounced in an older style of French vernacular or French

Latin to facilitate rhyme schemes and to add to the colors of the texts,

particularly the ballades that are simply musical poems. Finally, it is

important to resolve how to handle untexted musical lines. Scholars

still debate whether these are intended as instrumental or vocal parts,

but as Liber unUsualis is an all-vocal group and many of the pieces work

as all-vocal textures, the decision is whether to add a text or leave

the part on a single vowel. For each piece, a choice was made as to what

adds or subtracts to the text and if texting a line is even suitable or

possible.

The one piece not mentioned above is not by Machaut

but about him. In a great tribute, the poet Eustache Deschamps and the

composer F. Andrieu, both Machaut's contemporaries, prepared a double

ballade upon his death. Their tribute Armes, amours, dames, chevalerie / 0 flour des flours de toute melodie is perhaps the most eloquent and fitting description of the works and life of Machaut:

Tres doulz maistres qui tant fuestes adrois,

[O] Guillaume, mondains dieus d'armonie:

Aprés vos fais qui obtendra le choys

Sur tous fayseurs? Certes ne le congnoys.

Vo nom sera precieuse relique,

Car l'on ploura en France [et] en Artois

La mort Machaut, le noble rethouryque. |

Sweet master of skill so adept,

William, worldly god of song:

Who will win election after you

Above all artists? Surely, I do not know.

Your name shall be a precious relic, for

Men will mourn in France and Artois the

Death of Machaut, noble fashioner of song. |

ABOUT LIBER unUSUALIS

Hailed by The Boston Globe as "deeply moving," Liber unUsualis

is internationally recognized for their interpretation and performance

of medieval music, engaging audiences with inventive programming and

technical mastery of the repertoire. Since forming in 1996, they have

garnered critical acclaim both in the U.S. and abroad, as winners of the

2002 International Young Artist's Presentation—Early Music in Antwerp,

Belgium; an unprecedented "Honourable Mention" at the 1997 Early Music

Network's International Young Artists Competition (U.K.); and as

semi-finalists in the 1999 Concert Artists Guild's Competition (U.S.).

The trio has performed extensively throughout the U.S., and has

performed abroad at international music festivals in England, Wales,

Belgium, and Spain.

The members of Liber unUsualis (Melanie Germond, soprano; Carolann Buff, mezzo-soprano; and William Hudson,

tenor) each hold Master's degrees in historical performance from Longy

School of Music. This shared academic background allows the group to

unify their programs with research into both original manuscripts and

scholarly editions as well as a thorough attention to historical

context. The ensemble remains strongly committed to reaching beyond the

academic and technical aspects of performing Medieval and

early-Renaissance repertoire, continually exploring ways to express the

underlying emotion of the music. The group has presented several

workshops and lecture-demonstrations that emphasize their unique

approach to historical performance at Harvard and Tufts Universities, as

well as other academic institutions throughout the United States. Since

1999, Liber unUsualis has been Ensemble-in-Residence at the Episcopal

Cathedral Church of St. Paul, Boston where they present an annual

concert series along with performance workshops on various repertoires.

Liber

unUsualis has developed and performed a broad range of programs that

span from the earliest florid polyphony of the St. Martial repertory to

the refined harmonies of the Flemish Renaissance masters. The ensemble's

next recording project will be of their program "Forgotten Flyleaves:

Music of Medieval England," available on Passacaille in 2004.

Guest

artist Jordan Sramek studied early vocal performance at the College of

St. Scholastica in Duluth, Minnesota. Now a resident of St. Paul, he is

the Founder/Artistic Director of The Rose Ensemble and enjoys an active

freelance career as a singer, director and teacher. He was awarded a

Minnesota State Arts Board Fellowship for Performing Musicians in 2000

and received a 2002 Arts Board Career Opportunity Grant for his research

in medieval Irish chant and polyphony.

MANY THANKS TO

Simon Carrington

Mark Engelhardt

Pete Goldlust

Joel Gordon

Nina Hinson

Richard & Lois Hudson

Kathryn Karczewska

Scott Metcalfe

Michael Rogan & Hugh Wilburn

Gil & Nathalie Rose

Jordan Sramek

Catherine Stephan

Margaret Switten

and several much appreciated Anonymouses

who know who they are

|

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Recorded at Church of the Redeemer, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts

on June 4-8, 2002 (#2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11) & July 18-20, 2002 (#1, 3, 6, 9, 10, 12)

Recorded, edited and mastered by: Joel Gordon

Producers: Scott Metcalfe & Liber unUsualis

Design: Melanie Germond & Pete Goldlust

Translations: Dr. Kathryn Karczewska

Front Cover: Aquamanile: Aristotle Ridden by Phyllis, c. 1400

Southern Netherlands or Eastern France (Lorraine). Bronze

The Metropolitan Museum, New York. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

Photos of Liber unUsualis: Liz Linder

Ⓟ & © 2003 LIBER unUSUALIS

LIBER unUSUALIS

Info@liberunusualis.com

www.liberunusualis.com |